Welcome to my annual attempt to share what I feel are the best comics of the previous year (in this case, the books of 2016). Of course all the usual obnoxious caveats apply: a) that these lists are always only going to be a highly subjective record of tastes of a particular moment in a given segment of time; b) that it's virtually impossible and actually impossible to retain the same memory of a work read in January as it is of one read in November; c) that I of course haven't read a great many of the potentially fantastic works from across the year. All that's the same-ol' same-ol'.

I'll be including:

- Comics printed in collected form for the first time in 2016

- Comics printed as books for the first time in 2016

- Comics printed as books for the first time in the US in 2016

- Comics published on the web in 2016

- Comics published through digital subscription services like Crunchyroll in 2016

- Important comics reissued for the first time in many years

- Comics printed in December 2015 that I didn't see until 2016 (i.e. books that weren't released in time to reasonably have been included in my 2015 list)

(Example: I don't read comics as individual issues. Even though the entire Mind MGMT series ended in 2016, it didn't end until 2016 for me because I only read print comics series in collected form. So when I list Mind MGMT, which concluded for me in January of 2016 but seems super far away to you, now you know why I listed it.)

I believe that covers all my bases. Really though, I'm less interested in being a stickler for details than I am in just flat out recommending you some great comics reading from over the last year. So let's do that.

1–1011–2021–3031–4041–5051–6061–75

MetricsExclusions 1Exclusions 2Navel Gazing

My Best 75 Comics of 2016

Equinoxes

by Cyril Pedrosa

336 pages

ISBN: 1681120801 (Amazon)

Genre notes: day-in-life, ensemble

Equinoxes juggles the lives of about ten characters in France across the four seasons and ending in Summer 2002. Many of these lives are only tacitly related, interacting only glancingly at perhaps a single point in their histories. There are connecting threads, of course. A prospective airport and the mild political unrest it causes, a minister of the environment, a painting in a cave, a painting on a canvas, a handful of songs, and (most presently) a young woman with a camera. One of the principle characters remains obscure throughout but her fascination with an old camera gives the reader a window into many souls—every time she takes a person's picture the comics form is interrupted by the intrusion of a prose investigation of the captured individual, as if we're getting a sense of that person's conscious and subconscious self in the precise moment of the camera's click.

Apart from this particular conceit, the book also develops visually through the four seasons, with each being marked by a distinct alteration to the style of illustration. Either idiosyncrasy would be a fascinating aspect for Equinoxes to engage, but when taken together along with the superlative writing and thoughtfulness to the book, it becomes clear that Pedrosa's latest international release is something special—and in this present case, the best book of the year.

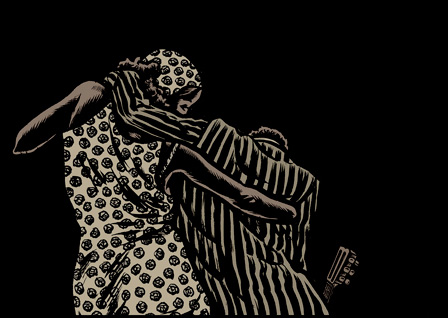

Hellboy

by Mike Mignola

14 vols

ISBN: 1616554444 (Amazon)

Genre notes: paranormal investigation, existential chaos/angst

Hellboy ended in 2016. And apart from some rare bumps in the road (always due to Mignola's collaboration with another artist or writer), the series has essentially just been the best comics. The series started off in a rough place, with bold beautiful art from Mignola, but also with janky, overheated, silly writing by John Byrne. By the time of the second Hellboy story ("The Wolves Of St August"), Mignola took over the writing and the book became the most amazing thing. And then it got better. And better.

And then, six years ago, Hellboy died. And went to hell. The final two volumes are just him wandering the non-heavenly afterlife and coming to terms with what his tie to destiny is or isn't. It's somber, funny, and bizarre. And gorgeous.

Hellboy (when done by Mignola) has always been a masterclass in comicbooking. His page design, his illustration, his tone balance, his writing. It's all nearly indistinguishable from perfection. Hellboy's concept is ridiculous pulp nonsense: a paranormal investigator who is actually from hell! But Mignola takes that and makes it not feel like pulp but Art and Literature. And as Mignola wraps the book with both a bang and a whimper, the reader will be forgiven for wanting to take it all in again as soon as possible. Sublime work.

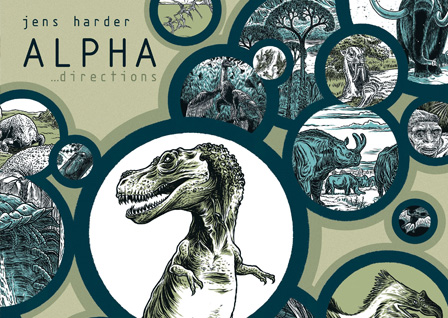

Alpha: Directions

by Jens Harder

362 pages

ISBN: 0861662458 (Amazon)

Genre notes: history, also like nothing you've ever seen

I wasn't sure whether to include this on the list. Technically, Amazon puts this as a late October 2015 release, but I wasn't able to get a copy until February 2016. My copy arrived from the UK. I'm not even sure it had an offical release in the US. Maybe it did, but it doesn't matter because there is an English-language version and you can acquire it. As to whether it belongs on a 2016 list or not, I'm erring on the side of I'd rather tell you about a great book than miss the opportunity because of a technical month or two.

Anyway, Alpha is a weird book. Or maybe not weird so much as maddeningly genius. It's part one of a proposed trilogy. Beta has already been released in German but Gamma remains only on the Potential horizon. It's too ambitious. Maybe it will never be completed but maybe it will. Fortunately, Alpha stands well on it's own.

Alpha presents the history of the earth from Big Bang through the cenozioc. Beta focuses on the rise of humanity from cenozoic to the present day. Gamma will tell the history of the world from today til the end of the universe. Where these books are unique is in the methodology.

Harder tells the story of the world through borrowed images. He came up with nothing in the book on his own. He drew everything, sure, but it's all redrawings of other things—from scientific illustrations, to illuminated manuscripts, to ancient maps, to sculptures, to comics and other pop cultural ephemera. You'll see things in panels in the pages I post that you recognize. Maybe it's Tintin, maybe it's Godzilla, maybe it's Goya's Saturn. The book, by its method, holistically draws from the whole of human history and experience and belief to make the story of creation our story.

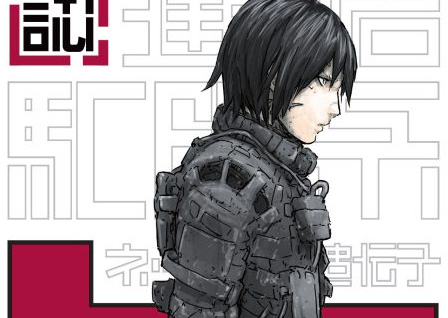

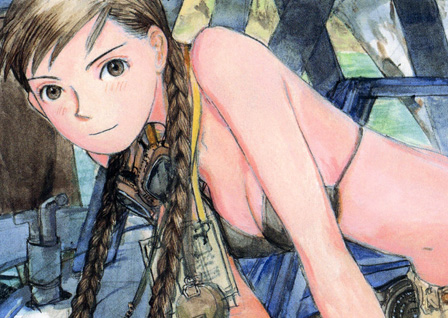

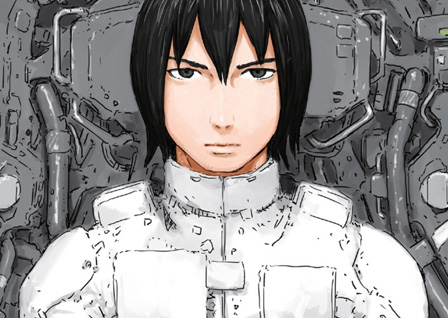

Blame

by Tsutomu Nihei

6 vols

ISBN: 1942993773 (Amazon)

Genre notes: speculative fiction, action, grotesque, whoa

Many of you may be aware of Tsutomu's work through Netflix's release of the anime adaptation of Knights Of Sidonia. KOS was his most recent series and it's polished and streamlined and tame. Still has some mind-expanding spec-fi going on in it, but it's tame nonetheless.

KOS is his third major series. Biomega is nutty and insane and rad and is his second series. Blame! is where he started off and it makes everything that follows feel a bit shabby. The art isn't as professional and tidy as Knights Of Sidonia, but this book has gumption.

Vertical is currently rereleasing the series in what's called the Master Edition. Probably to coincide with the animated series adaptation that I believe Netflix is picking up. The Master Edition is gorgeous. 7.25 inches wide and 10.25 tall and an inch-and-a-quarter thick. These are big luxurient paperbacks and really show off the unvarnished dynamism of Tsutomu's vision.

The story is about this guy, Kyrii. He's a bit quicker and stronger and more immortal than normal. He gets beat up a lot and he beats up a lot. He is scaling through the strata of this behemoth complex called the City to locate someone who still has the net terminal gene. This is far far in the future. Humanity has evolved down a variety of lines and there's been the introduction of some kind of mutagenetic infection. And when I say the City is large, I mean that it's grown enough to encompass Jupiter. Much larger than your average Dyson sphere. Life is cheap and rough and synthetics and ancient programs hunt down humans, so you can't really get too attached with many of the people Kyrii meets on his travels. It's rare they'll last long.

Glenn Gould: A Life Off Tempo

by Sandrine Revel

136 pages

ISBN: 1681120658 (Amazon)

Genre notes: biography, music

I got this for my wife for Xmas because she's a big fan of Glenn Gould. I wasn't even sure I'd ever heard him play (though I definitely have now). She really liked the book but wanted more details about his life. I, on the other hand, was bowled over by Revel's prowess as an illustrator—as well as her choices in how to visually narrate Gould's life from the side of his bed after the stroke at age 50 that would kill him within two days.

Revel's biography opens in Canada's Great White North with a wandering polar bear looking over at Gould, who plays an invisible piano in the middle of the tundra in tuxedo while wearing a dog mask.

It's an ambitious work, neither telling straight biography nor getting into the details of how he did what he did. Instead, Revel evokes the life lived through imagery that often does the opposite of overtly revealing the man at the center of the project. One of the best graphic novel biographies i've ever encountered.

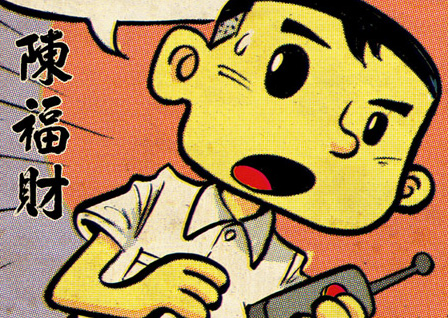

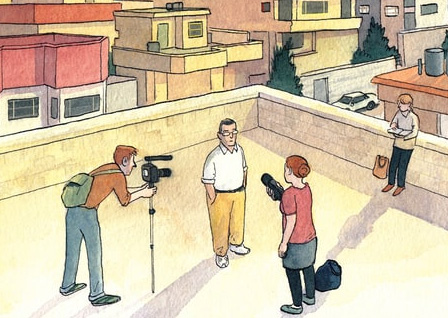

Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye

by Sonny Liew

330 pages

ISBN: 1101870699 (Amazon)

Genre notes: history, subversive trolling of a nation, art, comics

Sonny Liew's graphic novel masquerades as a retrospective collection of the life's work of Singapore's greatest cartoonist, Charlie Chan Hock Chye. In truth, there is no such artist, and the book is instead a roundabout way for creator Liew to unveil a counter-narrative to the Singapore Story, the official explanation of Singapore's path to independence and success. Liew's examination of Chan's comics across the decades brings light to the less-than-shining moments of Singapore's recent history and the policies of Lee Kuan Yew and lost an art grant from Singapore's National Arts Council for his trouble. A fantastic example of entertainment as more than entertainment; also a nice, brisk introduction to the island nation of Singapore.

Sunny

by Taiyo Matsumoto and Saho Tono

6 vols

ISBN: 1421579723 (Amazon)

Genre notes: drama, foster kids

Sunny is about a collection of kids interred at Star Kids Home in the late '70s. Some of these kids are straight orphans, some have parents who want them but can't support them, some have parents who just can't be bothered. The series is amazing and one of the best things going.

Matsumoto's evolving series of pericopes peeking in on the lives of the residents of a late '70s foster home is at once vital, brooding, joyous, grim, and heartfelt. It may be the perfect encapsulation of the human condition. And amazingly, the series improbably improves with each volume. In 2015's volume 5, I felt more and more the need for the series' finale in volume 6 to provide some sort of "20 Years Later" epilogue—if only for how crisply and seamlessly these characters have been brought to life for me. My heart pulls for these kids—and for the adults who mind them. With every victory I soar and with every defeat I sorrow. I can think of no better compliment than to say that Sunny is one of the most honest, affecting works I've encountered.

At the same time as things are falling apart and hope is being trashed, human nature is standing strong and willful. I wouldn't argue it's one of the most important comics series ever made, but if I heard someone make the argument I'd probably listen closely and nod along at appropriate points because I'd half believe them. I love that this exists and I love the care with which Viz has packaged it.

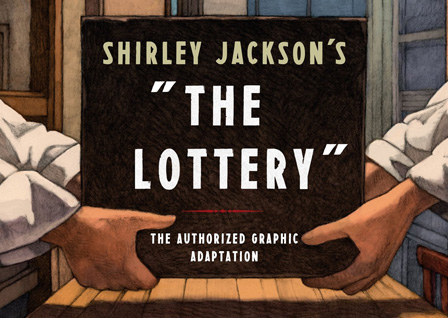

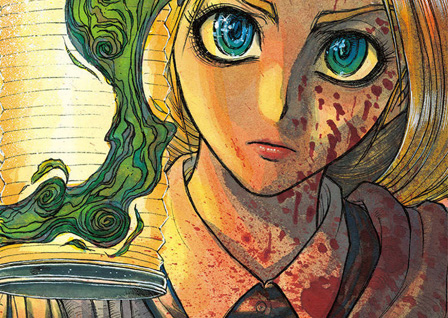

The Lottery

by Miles Hyman (adapted from Shirley Jackson)

160 pages

ISBN: 0809066505 (Amazon)

Genre notes: effed up classic American short stories

Holy cats. You guys. You guys.

When you see, Oh look, some guy adapted another piece of classic American literature into the graphic novel form, and you think, Oh joy, what a waste of time—when that happens, 10 out of 10 times you're on the right track. Skepticism toward comics adaptations of great literature is well-founded and merited. The products produced are always trash.*

But not this time.

Shirley Jackson's story is dark, sinister, and impressive. But for me, as good as it is, it was always waiting for this: the moment when Jackson's grandson would take his grandmother's signature work and draw the hell out of it, delivering this amazing thing that (for my money) actually improves on the original work. I don't understand his brand of witchcraft but I was awed. This is a gorgeous work, the illustrations lush and evocative. I was delivered into Jackson's world like never before.

__

*note: and okay, yeah there are other exceptions too, but allow me my hyperbole because I'm jaw-dropped excited for this particular adaptation.

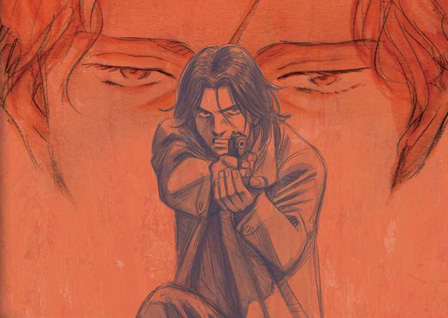

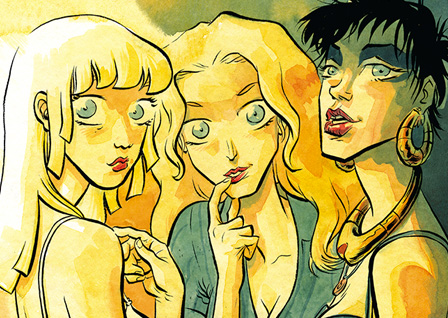

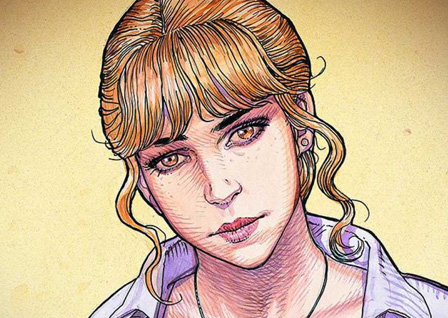

Last Man

by Balak, Sanlaville, and Vivès

6+ vols

ISBN: 1626720460 (Amazon)

Genre notes: fighting, adventure, romance, shounen

Last Man is pretty easily the most exciting series currently being published. Beyond being lithely and gorgeously illustrated by Sanlaville and Vivès (Vivès did A Taste Of Chlorine, which I mentioned a few posts back), the story is pulse-poundingly exciting. What begins as a magic fighting tournament in a rather fantasy realm turns into a cross-dimensional adventure when a theft speeds the recently arrived outsider Richard Aldana out of town in a hurry. Young Adrian and his mother give chase and things get out of hand real fast.

And the result is compulsively readable.

The artists portray so much elegance of motion that even heavy, stomping, oxen men move with a kind of liquid energy. Certainly more like a crashing wave than something more gentle, but still. More lithe figures like Adrian exhibit the same sense of weightlessness as the dancers in Vivès earlier work, Polina. The backgrounds, too, are skillfully devised with all manner of unexpected detail. A dragon here, a crowd reaction there. Altogether lovely.

But even better than that—and if you can imagine for a minute the essentiality of fluid combat choreography for this kind of story and then consider that this is better than that—the illustrators hold utter mastery of the characters' expressions. Their faces are simple but convey a wealth of intents and meanings. Child protagonist Adrian shifts from guileless to guarded to curious to excited to determined to overjoyed, and the purpose behind his countenance is never in doubt. Richard Aldana also modulates between a host of feelings and moods and interests. There is, at all times, the overt story being told through dialogue and action, but simultaneously there is another story told across the faces of this book's participants, a narrative born in looks and in eyes and in mouths and in shoulders and in the space of physical proximity, one character from another. This is a rich tapestry and this trio of creators demonstrates mastery of all the elements of their stage.

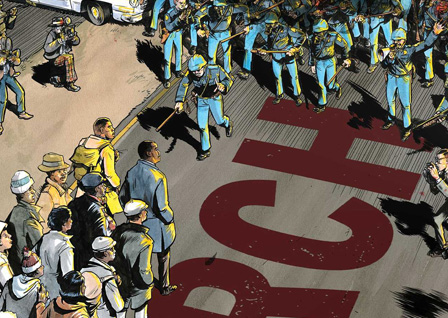

March

by Rep John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell

3 vols

ISBN: 1603093958 (Amazon)

Genre notes: biography, non-fiction, social issues

Just a couple reviews ago, I talked up the value of graphic novels in drawing out empathy in readers. For many of us, the best way to understand people who are different from us or other than us is not through dry academic description—much better to feel the life of another person as if you were intimately concerned with their fortunes. Representative John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell have succeeded tremendously in bringing a particular milieu of the middle of the twentieth century to a point of contact with the soul of the reader.

I did not grow up caring about the black civil rights movement. It was a distant thing. Like the Holocaust or Vietnam. Like trust-busting, flagpole-sitting, and chimney sweeps. I grew up on the beach in South Orange County across the ’80s. I was so deep into white privilege that I wasn't aware that racism was still a thing. Maybe in pockets in the South where all the backwards people lived. Again, a million miles away.

I had grown into a social ideology in which Colour Blindness was the ultimate expression of love one for another. It was what we were to evolve toward in our path to moral social perfection. I didn't really think of people in terms of their ethnicities or ancestries. Unless they had an accent. But then, there wasn't a lot of opportunity to practice interaction. White was the ninety-plus percent majority of my highschool. A handful of Latinos, some Asians, and like four black kids. There was, I think, also a French girl. She was more alien than any non-whites in our midst. I treated the black kids I knew identically to how I treated the white kids I knew. They were just friends or acquaintances or enemies like any other kid. So far as I knew, racism was a virulence that was choked out fifty years earlier.

Kids aren't great at putting themselves in other shoes.

I never once asked myself or my friends: Hey, what's it like to be the only dark face in a sea of blotchy pinks? I knew what it was like to be an outsider. Coming from a lower middle class family that struggled to meet ends, I knew what it was like to be an alien in what was and still is a ridiculously wealthy community. Having pretty bad acne, I knew what it was like to be uncomfortable in my own skin. Being a deeply shy introvert, I knew what it was like to have a lot of trouble socializing. Pursuing an avid comics readership, I knew what it was like to be ostracized for awkward tastes. I knew deep enough within my soul that it informed my every public action—I knew what it was like to be different. And yet I never once considered the lives and circumstances and histories of these non-whites in our midst. I was naive and careless enough to think that just treating people as I (an individual with my own life and circumstance and history) would wish to be treated was enough.

March presents a fantastic opportunity to remedy this kind of myopeia.

1–1011–2021–3031–4041–5051–6061–75

MetricsExclusions 1Exclusions 2Navel Gazing

Mind MGMT

by Matt Kindt

6 vols

ISBN: 1616557982 (Amazon)

Genre notes: espionage, extrasensory abilities, twisty thriller

A while back, I described the way I see Kindt as a creator: "Kindt strikes me as foremost an Idea Man. Everything he’s shown us so far paints him as prodigiously imaginative. He has big ideas for his overarching story, for the forms those stories take, and for some of the intricacies of how his pages and panels will lay out. I don’t look for any improvement on his part in this area. He has, so far as I’m concerned, arrived. If not perfect for what he’s doing, his ideas are close enough that we mere mortals cannot distinguish well enough to complain."

Mind MGMT does nothing to offer counter-argument to this conception of its creator. Kindt does show himself to be again prodigiously imaginative—and perhaps still moreso than in prior works. His attention to the intricacies of both his plot and the world he’s built for it to play out in is stunning. It’s hard not to sit slack-jawed and self-defeated when one comes across so sure-footed and designed a story as what Kindt regularly produces. It’s smart without ever passing into heady. It’s fantastic without breaking the conventions of believability. When I was in college, Mind MGMT would have blown my mind. The highest compliment I can pay it is to affirm that Mind MGMT blows my mind today, twenty years after my freshman year of college.

Theory Of The Grain Of Sand

by Benoit Peeters and François Schuiten

128 pages

ISBN: 163140489X (Amazon)

Genre notes: urban fantastique

Les Cites Obscure is Schuiten and Peeters' realm of fantastic cities and strange events. They exist in a world parallel to our own and many of the cities reflect our own world to degrees (for instance, the Palace Of Three Powers in Brüsel is a near replica to the Brussels Courthouse in, well, Brussels. Les Cites Obscure currently features in thirteen vols in France.

The Theory Of The Grain Of Sand is the second vol to be produced in the US. (The Leaning Girl, which I also highly recommend was released a couple years ago in a small run, but is now sadly out of print and used copies go for $125.)

In both US vols of The Obscure Cities, Schuiten and Peeters play on a combination of the overt and unexpected. The narrative of The Theory Of The Grain Of Sand concerns the appearance of some weird things: the multiplication of rocks of the exact same weight, a chef who is gradually losing weight but not mass, an apartment that produces sand, and more. But using the visual magic of comics, we find that these things are all related—because as one single character (and no other) can see, these things all shine and shimmer.

It's an exemplary exploration of the imagination—The Theory Of The Grain Of Sand is a strong work that boasts more of Schuiten's incredible linework.

The Eternaut

by Héctor Germán Oesterheld and Francisco Solano Lopez

368 pages

ISBN: 1606998501 (Amazon)

Genre notes: science fiction, subversive trolling of a nation

The Eternaut surprised me. I know it probably shouldn't have. Everyone was telling me to read it. But still…

There's this thing about a lot of older works that are well-venerated. Despite all their dignity associated with the place they hold in comics history, despite all the ways they influenced what we see in the field today, and despite all the ways they were actually really really good for their time—despite all these very important and legitimate things, many of the great works of the canon feel hackneyed and primitive when stood next to our contemporary greats. And no shade there, really. We should expect this. We should expect that when giants stand on the shoulders of giants they should loom much larger.

So when another wonder from a half century ago gets repackaged handsomely for a contemporary audience, I'm reluctant. I've been burned too many times, thinking I might find jewels relevant to my reading interests today. I imagine that somehow some long dead author might have anticipated the cultural condition I find myself in and have written to my particular milieu. And while that's at least plausible when we're talking about novels (after all thousands and thousands have been published every year for centuries), far fewer comics have been published and so the chance of genius spilling across time becomes slim.

The Eternaut, though. Man this feels fresh. Apart from some idiosyncracies native to the format limitations (one page per week in a newspaper), the book reads well. It's a longform, succinct story of the Twilight Zone variety that stands well apart from its contemporaries that I've encountered. This is sustained narrative while simultaneously having an end point, unlike the unending adventure-story engines of its North American contemporaries. Additionally, it offers some similar kind of political/historical commentary in the manner that Sonny Liew offers in The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye. I rarely feel I'm beholding something special when I read vintage comics, but I felt that with The Eternaut.

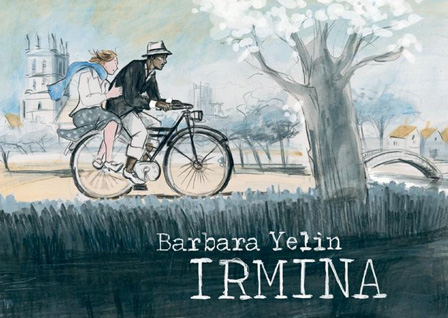

Irmina

by Barbara Yelin

228 pages

ISBN: 1910593109 (Amazon)

Genre notes: war at home, romance

The fact of Nazi Germany haunts the 20th century (and even still the 21st century) like a particularly strident and pernicious spectre. How? How! How on earth could Nazi Germany have been allowed, been encouraged?

A few years back Barbara Yelin discovered a box of her grandmother's letters and diaries. From that box grew the story of Irmina, a young woman who in 1934 was living abroad in London, gaining skills and forging a path for a future in which she could grab anything she wanted for herself as well as any man could. She is of course young and with youth comes naivete, willfulness, self-righteousness, and a colossal kind of self-centered ignorance. Still, how could that young woman of raucous attitude and vivacious heart be tens years later passively complicit in the Nazi machine, buying into (to some degree at least) the promise of volksgemeinschaft?

How could a young German post-suffragette proto-feminist go from being fiercely, desperately in love with a black man from Barbados and openly mocking Herr Hitler in the streets to working in the Reichskriegsministerium and chiding non-gung-ho friends with threats of reporting (I show some of this evolution in the accompanying pictures). From 1934 and though 1945 and then to 1983, Irmina paints a portrait, not just of a particular woman through the global scene of the 20th century, but really of how these vast shifts of paradigm are acquiesced to and adopted by the "ordinary" citizen.

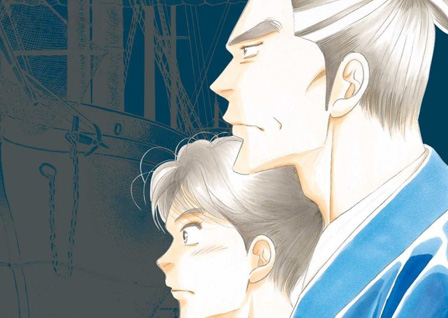

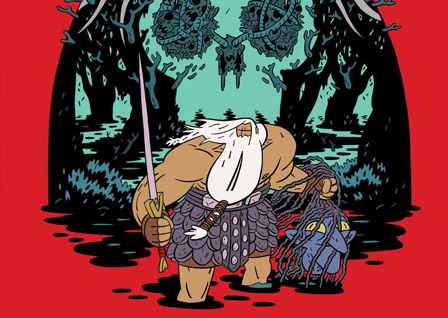

Vinland Saga

by Makoto Yukimura

8+ vols

ISBN: 1612624200 (Amazon)

Genre notes: historical fiction, fictionalized biography, Vikings, religion, war

Vinland Saga is a graphic novel series from Japan about vikings and pagan culture and Christianity and warrior culture and pacifism and revenge and redemption and having scary dreams about all the hundreds of people you've killed. It's loosely biographical, telling the life story of Thorfinn Karlsefni and his interaction with King Knut.

So there's this kid named Thorfinn who's set on avenging his fathers death. His dad was this epic warrior, the best of the best, but he gave it all up for something more powerful and became a pacifist. Then because when you're a jet, your a jet all the way, his old gang of super tough vikings have him assassinated. So Thorfinn's been part of this mercenary band since he was six, waiting for his chance at revenge. He's become this monsterous fighter, basically a superhero of murder but it's okay because vikings are all about battle and war.

Then events conspire so that his reason for living vanishes. There's no longer any vengeance for him. He's rudderless until he remembers some stray words his father spoke. This combines with a lot of talk about Christianity (if you remember history, the was a time of great conflict and mashups between Odin worship and the Christian mythos).

So suddenly, after 1700 pages, we finish Chapter 54, which is titled "the end of the prologue." The book has been 1700 pages of brutal war. It's a bloody violent action-lover's dream (with a sprinkling of religious and politic talk to make it feel not entirely like a dumb superhero book). And suddenly, [END OF PROLOGUE SPOILER] the action hero—this unstoppable warrior—takes a vow of pacifism, becomes a slave on a plantation, and starts living toward the goal of building a world of peace.

I mean think about that, it's pretty brassy to put together what is basically a brutal action adventure story and then suddenly after 1700 pages get your readers on board for a book about a guy who won't fight back. It would be like Christopher Nolan making The Dark Knight Rises into a movie where Bruce and Selina wander around Gotham City chatting and at one point they get mugged and Bruce gives up his wallet and maybe offers the mugger a job at Waynetech.

I find the book fascinating, not only because of how it incorporates mature and varied discussion of faith and its consequences (which are pretty much totally unexpected in the genre), but also because it implicates the reader in Thorfinn's violence. You hear that kind of thing a lot, a book or movie or videogame implicates the reader in this or that, but I think Vinland Saga really drives it home after Thorfinn puts off his old man to become a man of peace. You have this warrior who's both incredibly skillful and incredibly savage, who could kill ten men in a flash. And he gets confronted with unjust violence or theft and you just want him to strike back, you want those who oppose him, those who would abuse him, to know the fear they ought to have for him. You want catharsis and vindication—and because you're wanting violence and the hero instead offers the other cheek, you're left feeling the power of that decision.

So far, vol 7 is my favourite of the bunch for its truth-to-power moments, and the conversation between King Knut and Thorfinn where Knut (the Christian) said that God has failed us and that we've got to subjugate the world with terror and violence in order for some of us to know peace, and Throfinn (the pagan) is like, "Nuh-uh, bruh."

Yotsuba&!

by Kiyohiko Azuma

13 vols

ISBN: 031631921X (Amazon)

Genre notes: comedy, daily life, children

Yotsuba&! is a source of deep magic for me. And, I suspect, for a great number of others as well. Kiyohiko Azuma's series is an unexpected pleasure. Even if one approaches the work with the knowledge that Yotsuba&! bubbles forth as a fountain of joyfulness, this little girl's nature and adventures will still surprise in how purely they deliver one into this momentary Other Place.

Four-year-old Yotsuba's sense of wonder in the way she approaches an environment with which she apparently has had no experience is astonishing in its guilelessness. Yotsuba brims with enthusiasm and the pleasure with which she takes on each new experience leaves us breathless as that enthusiasm spreads. Her father is consistently amused by her naïveté and her neighbours are never certain what exactly to make of her. And yet, she really does inspire affection in everyone she encounters.

My descriptions can only serve as a diminishment to what pleasures are actually found in the book. I am entirely out of my depth to sound out Yotsuba&!’s charms, but perhaps we should just leave it at this: whenever a new volume arrives in the mail, I curl up comfortably with my wife, finding the best lighting possible under such snuggly conditions, and I read each chapter to her aloud, trying to muster in my own voice the clear enthusiasm in Yotsuba's own.

And then we both smile a lot.

Also, vol 13 introduces Yotsuba's grandmother and it's worth it.

The End Of Summer

by Tillie Walden

108 pages

ISBN: 1910395269 (Amazon)

Genre notes: family dysfunction on a grand scale, cabin fever

So there's this family that's super wealthy. And they live in a place where winter is 3 years long and kills everything that's not sealed up and warm. And three years is a long time to wander around even a magnificently large house.

The End Of Summer is basically about Lars, who with his twin sister Maya, is one of seven children of a fabulously wealthy family in just such a place and at just such a time. Their house is cavernous and ornate and amazing. Lars is sick with a sickness that means he won't last the three years. His family knows he's sick but doesn't know this is the end for him. He also rides around on a gigantic cat named Nemo because he'll get too winded otherwise. Lars isn't the only one in trouble though and as I said, three years is an awfully long time to be cooped up.

Walden's illustrations are a dream and she tells a story that takes in the architecture of the place every bit as much as it does the architecture of this family and their interrelationships. It's a quiet work punctuated by moments of human terror. It is worth your attention.

A Girl On The Shore

by Inio Asano

1410 pages

ISBN: 1941220851 (Amazon)

Genre notes: drama, manga, romance, school

A Girl on the Shore opens with an awkward post-coital walk along the shore of a somnambulant little town in which two ninth graders discuss whether to forge a romantic relationship out of what the girl viewed as a virginity-losing one-afternoon stand. The girl, Sato, wanted a bit of sex in order to feel something, to rage against the way another boy (the one she pines for) abuses her and is dismissive to her. She instinctively reaches out for a measure of control and convinces Isobe, who's long been attracted to her, to put a little sugar in her bowl (to euphemistically borrow from Nina Simone). She knows he will, and so she takes advantage of that attraction. She's still unfilled, but she's awakened a curiosity and a need.

All of this happens before page 1, and Asano allows us to join them in media res as Isobe asks Sato if she wants to be his girlfriend. But she doesn't think of him like that and cannot be involved with him romantically while she is hoping against hope that Misaki, the cad of her dreams, will finally return her affections. It takes a couple days, but Isobe and Sato iron out a kind of rhythm in which they engage in frequent, escalating, no-strings-attached sexual exploration. The trick of course, as every story ever has taught us, is that we can't always see the strings that guide us, bind us, and draw us. Especially not when our eyes are glued tight in orgasmic ecstasy.

Things play out as they will as the kids head toward graduation and on to high school, and everyone discovers that the things they believed so deeply and strongly were most likely only their eager imaginations, fueling and burning in engines of youthful madness and indiscretion. There's a certain profane beauty and chaos to it all. In some ways it reflects the common boy-girl experience and in other ways is horrifyingly unique. There is nothing healthy being explored, but the whole experiment was never about health. It was about overcoming alienation and extorting life into healing without bandaids or antiseptic.

Vattu

by Evan Dahm

3+ vols

Read/purchase

Genre notes: adventure, politics, anthropology

While Rice Boy was fascinating and inventive and Order of Tales offered a superb yarn, Evan Dahm's Vattu is his most ambitious story yet—a multithreaded, complex narrative about the crossing of cultures, imperialism on the verge of post-imperialism, the semitotics of identity, and how language shapes us.

While Rice Boy's colours were flat and Order Of Tales was black and white, Vattu is vibrantly coloured with a perfection of details. It's a beautiful book. I'm hungry to see the story complete if only because I 1) love the satisfation of a story concluded and 2) can't wait to see more stories in Dahm's world.

Nod Away

by Joshua W. Cotter

240 pages

ISBN: 1606999117 (Amazon)

Genre notes: science fiction

It wasn't immediately clear to me that Nod Away is the first vol of a longer series (1 of 7, I read). There's a numeral 1 on the spine but it wasn't prominent so I ended my reading, interested and happy to have read the book, but also confused. Knowing that the story will continue alleviates every single concern I felt while reading. It's a strange and interesting book that leaves the reader with a lot of questions, but it's well-done and intrguing enough that I'll be excited to see where Cotter takes us next.

1–1011–2021–3031–4041–5051–6061–75

MetricsExclusions 1Exclusions 2Navel Gazing

Planetes

by Makoto Yukimura

2 vols

ISBN: 1616559217 (Amazon)

Genre notes: science fiction, existential angst, the power of love

When Planetes came around the first time with the 2000s manga boom, I skipped on it. I'd heard good things but I'd also heard it was about garbage collectors in space. Which was a turn-off because I kept picturing Emilio Estevez and Charlie Sheen in space, but minus the nostalgic fun of having the actual Estevez and Sheen to keep me invested.

Fortunately, between then and now I'd taken the opportunity to read Vinland Saga, which is good enough to put me in the position of implicitly trusting Yukimura prety much forever and always. Vinland Saga earned my interest in Planetes—and it's an interest well spent. Planetes is not as singularly interested in developing a plot as Vinland Saga and it roams around a bit, giving breathing room to its characters and stories, but it's a good book. Maybe even very good (even though we try not to say that sort of thing here and it edges suspiciously close to acknowledging the possible existence of a fourth review star). Just as Vinland Saga, Planetes is thoughtful and proposed that the reader spend time thinking about life and its value and meaning and purpose.

It's only two volumes—pick it up.

Wild's End

by Dan Abnett and INJ Culbard

2+ vols

ISBN: 1608867358 (Amazon)

Genre notes: adaptation, zoomorphs

This list could be read as a summary of what I'm resistant to and what I hesitate to spend my time on. I've already admitted reticence about The Eternaut and Planetes, and these are far from the last books on this list that I hesitated on. But yes, Wild's End is among this number. I would have left it unread (despite praise from elsewhere) had it not been for INJ Culbard's involvement. (I've been a fan of Culbard's since reading his and Edginton's adaptations of Sherlock Holmes nearly a decade ago.)

I'm not super into books about zoomorphs (my longstanding love for Usagi Yojimbo is a notable break from my genreal rule), and I've read enough revamps of War Of The Worlds to last me a lifetime (one even written by Culbard's own occasional creative partner, Edginton). But Abnett and Culbard pull something magical out of their hat. This is perhaps the first time that I've been excited by an alien invasion story since I read the original War Of The Worlds in fourth grade. Their cast of characters is luminous (sometimes literally) and it's their stories that give life and meaning to the soulless invasion of these foreign beings.

Also, and this is something remarkable. I pretty much never read the prose extras that some authors will include in the back-matter of their comics. I think I read a paragraph and a half of Alan Moore's backmatter for one of the League Of Extraordinary Gentlemen issues. That kind of stuff really knocks the wind out of my comics-reading sails. I'm here for the concatenation of word and picture. It's in that chemistry that I find my joy. And I don't know what prompted me to give it a shot, but I devour the back matter in each chapter of Wild's End. They are superbly accomplished and they add so very much to the experience of the story and these characters that the book would feel hollow without them.

Ooku

by Fumi Yoshinaga

12+ vols

ISBN: 1421527472 (Amazon)

Genre notes: history, alt-history, gender roles, internecine political madness

Ooku: The Inner Chamber just keeps on trucking. It's an alt-history of Japan. During the third shogunate (what, around 1625 or so) the country gets swept with the red-face pox, a pox strain that Y-The-Last-Man-style only affects males. Only 20% of the male populace survives so society (and even the shogunate) switches to a female dominated life and governance.

The cool thing is that despite the switch, Japanese history is essentially unchanged. All the shoguns and all their stories and all the Japanese events remain unchanged save for that now it's women in the same roles. So you're getting this amazing story that is basically just a trick to get you to read Japanese feudal history and think about women outside their traditional roles. And it's amazing.

And there are some seriously deeply Machiavellian nuttos up in this thing. Poisonings are rampant. Scandals, beheadings, coups, maneuvering, jockeying heirs, the whole shebang. It's madness and you want so badly for some catharsis and for the villains to get theirs. And sometimes you get that but a lot of times the bad guys just win and never suffer a single consequence.

And the crazy thing? All of this really happened because Yoshinaga is just telling you the story of Japan.

Vol 12 just came out and those 12 vols cover a space of about 200 years. I don't know if vol 13 will be the finale, but it certainly feels like it could be drawing to a close. (The series was originally slated to run 10 vols but the story was just so big.)

Rachel Rising

by Terry Moore

840 pages

ISBN: 1892597616 (Amazon)

Genre notes: horror, dark humour, history

Rachel Rising begins with a woman crawling out a shallow grave in a ditch in the woods from where she was assaulted then murdered. It took me about 500 of its 900 pages to even figure out what kind of book I was reading. It was always very good but I just couldn't get a handle on what tropes I should be expecting. That is a good kind of place to be.

Rachel Rising mixes in horror, dark humour, Jewish myth, a town with a history of witch trials, and the supernatural. The principal characters are all women. There is one male supporting character and he's sweet and gentle and good. Terry Moore has been self-publishing his comics since 1993 and Rachel Rising is his third major work—and first horror book.

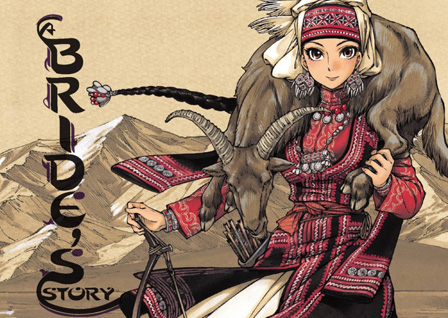

A Bride's Story

by Kaoru Mori

8+ vols

ISBN: 0316317624 (Amazon)

Genre notes: history, anthropology, romance

In A Bride's Story, Mori deposits the reader leagues away from the British romance of manners she crafted in Emma, instead exploring rural and nomadic life along the Western track of the Silk Road during it's diminishment in the Great Game era. While Mori has so far largely focused her attention specifically in what is probably central Kazakhstan, near the expanding Russian border and off a bit from what used to be the Aral Sea, she's been simultaneously following a narrative track that allows her to explore increasingly Muslim lands as she follows a character's trek around the Aral and south around the Caspian on his way to Ankara in Turkey. The cultures she describe are rich in a heritage and practice that will be largely unfamiliar to the average Western reader. This is a land of yurts, shepherds, big families, khanates, delicate carvings, intricate weavings, and ornate embroideries. Much of A Bride's Story serves as educational documentary, explaining carefully the importance of these facets of the peoples the story concerns—and it's a mark of Mori's talents that these lessons are never dull. The story, while pausing its plot elements for a description of tribal politics or the importance of rug-hanging, is built and embellished and given life through these brief excursions.

The most obvious of the more unique aspects of the culture Mori explores in A Bride's Story is this people's tradition for youthful marriages. The author explains in her endnotes to the first volume that the average marrying couple in the region would have been fifteen to sixteen years of age. For dramatic purposes here, she adds and subtracts four years from the average for her principle couple—though in a subversion of the trope, the bride is twenty and the groom only twelve. This creates numerous opportunities for thoughtful consideration of how different cultures might deal with the man/woman dynamic—as well as plenty of related awkwardness for both reader and characters alike. Amir, the bride, is often torn between mothering her young husband, Karluk, and approaching him like a young woman who is gradually falling in love. Further adding to the dynamism of the work is the fact that at twenty years old, Amir is viewed by her society as an old maid and there is no small concern that Karluk may have been slighted by being given a wife who will likely bear him few children. Amir, therefore, is eager to please her husband and new family, which gives Mori ample opportunity to display the bride's considerable talents. Amir hunts, herds sheep, embroiders, shows a talent at horsemanship to rival any of the men in the family, and has a good decorative sense.

A Bride's Story offers contemporary readers a delightful opportunity to exercise the skill of reading and enjoying a text without finding moral agreement with the circumstances, actions, or particulars of its protagonists. For this reason, A Bride's Story may even be desirable to get into the hands of younger readers (despite some occasional nudity—or substantial nudity once vol 7 rolls around since much of that volume occurs in a women's bath house) if for no other purpose than to promote this critical ability at an early age. Mori makes this an elementary text for this kind of exercise. Almost no American reader will approach the text thinking it good or appropriate that a grown woman should marry a boy who is only straddling the boundary between childhood and puberty—yet that is the circumstance this culture forces on its two very winning protagonists. Further, the reversal of the autumn-spring relationship trope presents opportunities to consider the contemporary sexual politic. As well, it's interesting to see a situation in which a clearly competent, intelligent, and mature woman willingly places herself ultimately under the authority of a child (a kind child who evidently cares deeply for his new charge, but nonetheless…).

In the most recent volume, Mori returns to a character and storyline introduced in the first volume. Amir's first friend in the village, Pariya is attempting a courtship but is all kinds of awkward and frustrated because her personality isn't the meek, quiet kind of woman that many in her society expect. Her story doesn't wrap up in volume 8, but hopefully will see her success or failure come to fruit in vol 9.

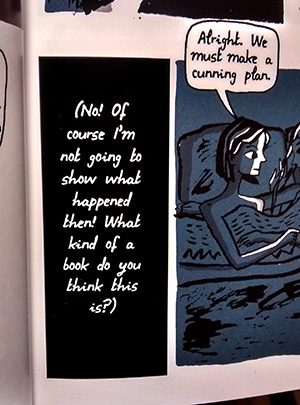

The One-Hundred Nights Of Hero

by Isabel Greenberg

224 pages

ISBN: 0316259179 (Amazon)

Genre notes: fable, mythos

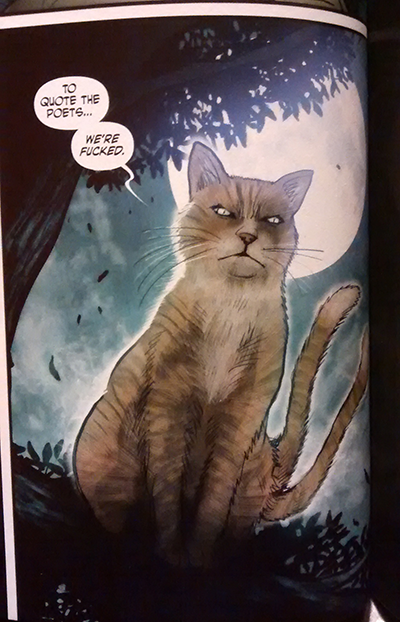

I hadn't read Isabel Greenberg's Encyclopedia Of Early Earth (thinking by its title that it was some children's graphic novel-style presentation of Mesopotamian history and culture), and so I was unprepared for the cut of her narrative jib. I was enjoying the funny little mythos unveiling in The One Hundred Nights Of Hero when I came across what felt like an intrusive bit of authoring. Two women are snuggling in a bed and then there is a panel of all black with white text, saying:

It hit me funny and took me out of the book for a moment in a way I didn't appreciate. It felt entirely too glib for the wonderful fable I was being allowed to observe unfold. I put the book down and came back to later that evening.

My reader's expectations had, of course, abused me. I thought I was reading one kind of book (a sober, reflective story about kings and gods, perhaps), but that was my mistake. This wasn't ever going to be any kind of a snooty, lofty, huffy kind of a book. It may reach for a kind of nobility, but instead of anything approaching the coolness of acadmeic self-importance, The One Hundred Nights Of Hero is lively and warm and takes a fierce sort of off-the-cuff joy relating one primary thesis: that there is both joy and power in Story.

I was foolish to let my expectations carry me away, but Greenberg's work is strong enough to have easily brought me back into its fold. (As soon as I get some money, I'm going to be challenging further our quickly diminishing shelf space by purchasing her earlier work, Encyclopedia Of Early Earth.)

Their Story

by Tan Jiu

online

Read here

Genre notes: romance, comedy, lgbt themes

This high school romance between two teen girls in China is still rather one-sided in the romance department (in that one of the girls is deep in the crush of new love and the other is just happy to have a new friend), so there's lots of that dramatic tension that naturally draws from the Unrequited Love engine. Also, Tan Jiu keeps her lead charming and emotive, so it's a pleasure to watch her do whatever it is she's going to do at any given moment. This is so far only available on the internet, but as soon as there's a physical product, it will enter my library.

I'm not super familiar with the Chinese comics scene. That is, I'm not familiar at all. I've read (possibly) five Chinese comics ever. I don't know where Their Story fits within the industry there, but if a story as buoyant and bubbly and fun and straight-up enjoyable as this is at all common there, then the Chinese comics industry must be one of the best things ever. If it's not, then at least they've got a great example of where to aim. Their Story is one of my favourite things coming out right now.

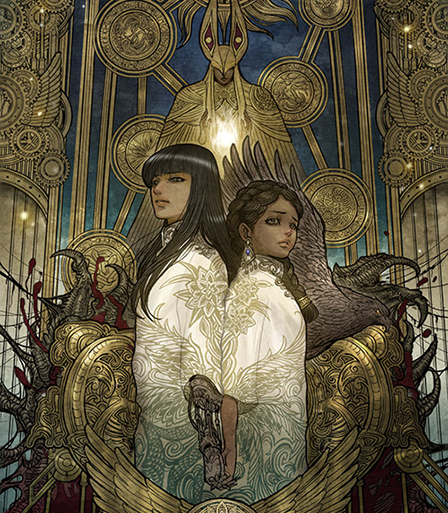

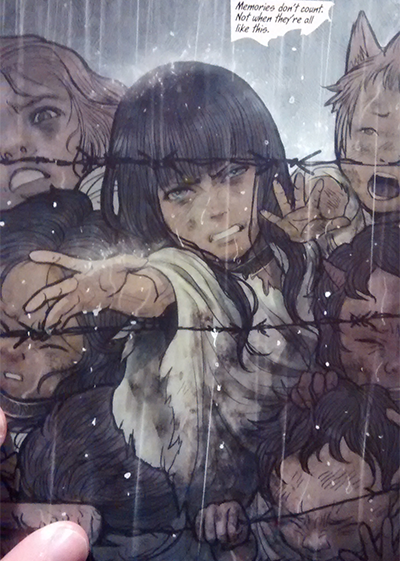

Stand Still Stay Silent

by Minna Sundberg

1+ vols

Read here

Genre notes: Post-apocalypse, adventure

Post-apocalyptic zombie fiction has never been better. Which is good because the post-apocalypse is pretty well played out and man do I hate zombie fiction. But Sundberg's vision here is almost entirely unique in every way.

1) The remaining civilized world is so far limited to Iceland, fortified pockets of Norway, Sweden, and Finland, and a single island of Denmark. That's a rare and interesting setting for a story told in English.

2) The zombies aren't zombies like we typically think of zombies. There're also corrupted beasts and now a bunch of super-interesting ghosts. The lore of this new world is extensive, detailed, and imaginative.

3) Sundberg's art is gorgeous. It's luscious and the way she affects mood through colour is essentially like nothing I've seen.

The series continues online but I look forward to the release of volume 2.

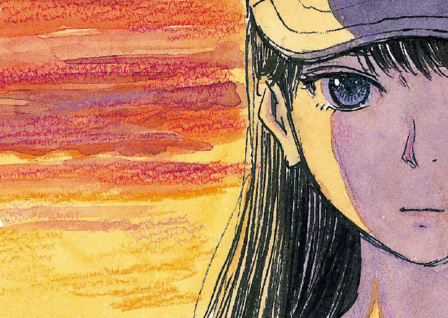

5000 Km Per Second

by Manuele Fior

144 pages

ISBN: 1606996665 (Amazon)

Genre notes: romance, drama

A boy and a girl and their relationship to and apart from each other evolves over both distance and time. A story about the way we are broken and can break one another and whether there might be solace regardless. Beautifully painted.

Emma

by Kaoru Mori

5 vols

ISBN: 0316302236 (Amazon)

Genre notes: victorian romance

Emma is chiefly the story of Emma and William, an orphaned household maid and the son of the monied class. This is a romance and we see them meet-cute, fall for each other in that stereotypically understated Victorian way, encounter difficulties due their class distinctions, and finally resolve their relationship. It's a lovely little story.

As Emma is the story of two principles, Mori leaves every other story untold. While William and Emma's story finds its resolution, a reader could easily become frustrated with the many loose ends Mori leaves untied in her supporting characters' regard. Personally, I found this abandonment of other characters charming and felt their untold stories just added to the book's wonder. Because of Mori's reluctance to end all stories with the conclusion of Emma and William's story, she keeps Emma from being yet one more example of contrived romance.

Mori's storytelling is impressive. The weight of her line perfectly suits her subject matter; it's crisp and confident. She excels at choosing setting, pace, and moment, giving her characters the opportunity to reflect on actions, words, or thoughts from prior panels and pages. As well, Mori includes any number of silent scenes, allowing the reader to pause and take in the full scope of what is occurring within the more introspective parts of her characters stories. Keeping the reader involved, Mori uses a number of visual devices, requiring one to pay attention to camera angles and character details. The storytelling occurs as much through visual relief as it does through verbal narrative and dialogue.

1–1011–2021–3031–4041–5051–6061–75

MetricsExclusions 1Exclusions 2Navel Gazing

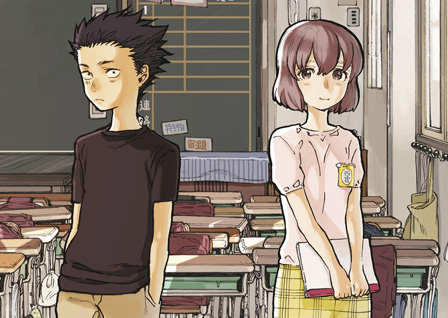

A Silent Voice

by Yoshitoki Oima

7 vols

ISBN: 163236056X (Amazon)

Genre notes: school, disability, bullying, romance

A Silent Voice begins with the story of two kids in elementary school—Shoya the reckless, popular kid and Nishimiya the new girl, who is deaf and communicates through writing in a notebook (since nobody knows sign language). Nishimiya's inability to hear and the problems that crop up as a result are too strange for Shoya and so, leading by example, he creates an environment in which Nishimiya is bullied daily and with extreme prejudice. She is scorned, mocked, and has her hearing aids repeatedly torn from her ears and destroyed. When it eventually becomes too much, the girl's mother complains and all blame is pushed onto Shoya's shoulders. From that point forward, he is systematically bullied by his former friends in a manner far more vicious than that with which he instigated against Nishimiya. His resentment against her swells, and he gets into a fistfight with the girl, prompting her mother to remove her from the school. Six years pass and Shoya endures trouble all through elementary school and junior high. Through hindsight and reflection, he finds himself reevaluating those early days, and now as a highschooler, Shoya seeks to have one final, repentant conversation with Nishimiya before removing himself from the world.

And the story moves on from there.

A Silent Voice is concerned with the transition from sociopathy (non-clinical) to empathy. Just as I had to evolve from my early-twenties experience of passive aggression, so does Shoya seek to learn how to melt from his seclusion and inability to relate to others. While the details of his path are different from my own, it's comforting to see the generalities are not unique to myself. I don't usually look for representations of myself in the literature I take in, but for whatever reason I appreciate it in this case. Perhaps because I know that Shoya's story will end happily, it provokes hope for the conclusion to my own story.

Horimiya

by HERO and Daisuke Hagiwara

6+ vols

ISBN: 0316342033 (Amazon)

Genre notes: progressive romance, romcom, high school

Omigosh, this is book is the cutest thing ever. Basic idea: The story is about 1) Hori (the girl), a gorgeous high-achiever who outside of school wears sweats, no makeup, etc (basically she is a real person and is not 100% made up 24/7 but that is weird either in Japanese cultural or maybe just in Japanese pop cultural confections like this comic) and about 2) Miyamura (the boy), who in school appears a gloomy four-eyed otaku but outside of school is a good-looking, pierced-and-tatted dude who catches girls' eyes. They accidentally discover each other's real selves and it goes from there. They become friends and help keep each other's other seleves secret from the swirling populace of the highschool dramamill. And then the boy/girl thing starts to happen.

Horimiya, the book's title, is a portmanteau of Hori and Miyamura. Kind of, I guess, like Brangelina.

Among the neat things is that Horimiya is a progressive romance (i.e. one that moves beyond the will they/won't they question and explores their life as an established couple and beyond). It doesn't happen right away and the book follows their awkward courtship before courtship, the sort of mutual friendzoning in which they're each terrified to find out exactly what they mean to each other but it moves beyond that and into the struggles, joys, and rhythms of life as a couple.

It's good. It's real good. And I laughed a lot. The artist's ability to capture expressions is great.

Also: tidbit. HERO-sama is the woman who wrote/drew the series Horimiya is based on (Hori-san And Miyamura-kun). HERO's art is, well, rather amateurish, so i'm glad they Hanigawa was given the opportunity to adapt the original comic.

Monster

by Naoki Urasawa

9 vols

ISBN: 142156906X (Amazon)

Genre notes: crime thriller

Urusawa's story about an unstoppable killer vs the doctor who saved his life as a child is overlong and thickly padded, BUT it's also pretty wonderful, pretty thrilling, and pretty great at giving life and meaning to its large supporting cast. I prefer Pluto and 20th Century Boys, but Monster is impressive and is in no way a waste of a reader's time or resources. And the new edition by Viz is handsome enough (even if the covers are ugly as sin).

Dorohedoro

by Q Hayashida

19+ vols

ISBN: 1421533634 (Amazon)

Genre notes: body horror, fantasy, bizarro, people turning into meat pies

Dorohedoro has been truckin' along for years but it finally feels close to wrapping up. Volume 19 landed in 2016 and the story and invention seem just as imaginative and bizarre as they did on Day 1. Maybe actually moreso. I have no idea what to expect from a finale, but Q Hayashida continues to impress.

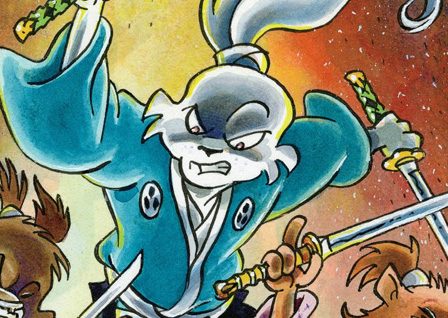

Usagi Yojimbo

by Stan Sakai

30+ vols

ISBN: 1506700489 (Amazon)

Genre notes: samurai, historical fiction, zoomorphs

Usagi Yojimbo is the story of a fictional, idealized, totemic, and somewhat historical Japan. It is a story told by following (primarily) a single wandering ronin as he follows the way of the samurai, seeking enlightenment, honour, justice, and the beauty of living. Due to his wandering nature, the reader encounters a breadth of stories, regions, and cultures. These tales unfold circa 1627 and create, despite their (sometimes) almost mythical hue, a worthwhile vantage into real and historical Japan.

Sakai peppers his narrative with the fruit of a lot of research. The most popular of his stories, “Grasscutter,” begins with a lengthy-though-entertaining excursus into the mythological origins of Japan and her people. A shorter story, “Daisho,” explains the craft with which the samurai’s sword-pair is forged and the importance those two swords (called daisho) hold to their owners. Other chapters include overtly educational bits on kite-making, pottery-making, and the intrusion of the West into the Far East. And even when he isn’t completely halting his telling in order to instruct the reader, Sakai weaves a story that posits a seamless, discreet form of education—taking part in the story by simply reading it, Sakai’s audience is constantly learning more and more about a dead and foreign culture.

One of Sakai’s great talents is in his visual storytelling. His art flows naturally and his panel design is masterful. Some of the most beautiful pages are silent and filled with panels; each of these panels illustrates part of a picture-story that initially seems unrelated to the narrative intent but ends up providing context or mood for everything that is to follow. Sakai’s art has a wonderful, lyrical quality to it and it’s incredible that he’s been able to maintain his more-than-twenty-five-year schedule of producing one chapter per month. He really is one of the best creators in the medium.

30 vols is a lot to take in. If you want a nice place to start, to see if this is a book for you, I'd recommend read vol 28, then 29, then 30 and backtracking from there if the story suits your tastes. These are exemplars of what Usagi Yojimbo is all about and 2016's vol 30 continues this trend.

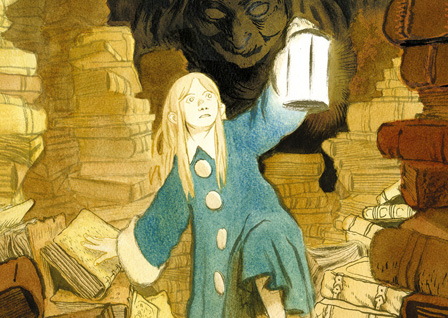

Koma

by Pierre Wazem and Frederik Peeters

280 pages

ISBN: 1594651477 (Amazon)

Genre notes: surreal adventure

A surreal adventure in which a young girl who falls unconscious (because her machine located in the underworld and maintained by a strange dark creature is defective) may be the only hope for the waking world—only in a completely non-shounen way. Peeters continues his trend of working on weird projects. It's a good trend and one he's well suited for. And at one point we see precognitive echoes of some ideas we'd later see at work in Pachyderme (Koma is an older work, just now being localized for American consumption).

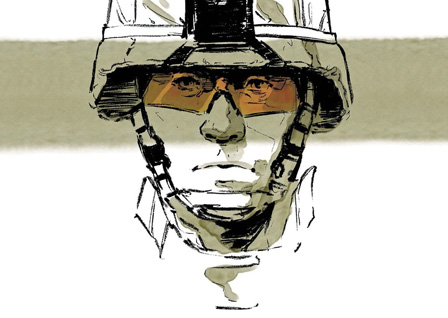

White Donkey: Terminal Lance

by Maximilian Uriarte

288 pages

ISBN: 0316362832 (Amazon)

Genre notes: military, marines, PTSD

A "friend" recommended this to me earlier in the year and I kind of hate him for it, because as I read in Starbucks I sat there blurry-eyed and hyperventilating because I just saw in graphic detail how a kid I used to teach died in Iraq in 2007. The circumstances were identical.

Reading that scene was shocking and horrible and brought back a lot of anger in me that had largely simmered down in the decade since. Anger at our leaders for spending young lives so prodigally. Anger at our culture for making signing up for old rich white men's wars seem like a glory and an adventure.

My friend signed up for a mix of motivations. He wanted adventure and he wanted to live in honour of the memory of another friend who had signed up and died in Iraq. Maybe it was Afghanistan. I don't remember. He was a lance corporal too, like the guys in this book. And the hole he left demolished a lot more than his own life. My brother worked with one of his best friends (non-military) years later and the guy was a shelled out mess.

All of that may render me incapable of approaching White Donkey with much objectivity. It's a good book, I think. One that takes you through the brief career of a Marine, from training to promotion to deployment to return to... after. It's written by a Marine who was in Iraq for four years and casts a wry look at the mechanism of the American military. It's funny and sad and is born out of his own experiences with fear, jubilation, trauma, loss, and hope.

Geis

by Alexis Deacon

96 pages

ISBN: 1910620033 (Amazon)

Genre notes: fantasy

Geis is only the first volume in a fantasy story but already it captivates. Despite the fantasy setting with wizards and witches, Geis avoids feeling dated and worn while not stooping to the kind of glib too-cool-for-schoolness you'll find in so much of Image's sci-fi/fantasy catalogue. Looking forward to seeing where Deacon takes this train.

Carthago

by Christophe Bec, Eric Henninot, and Milan Jovanovic

284 pages

ISBN: 1594651515 (Amazon)

Genre notes: adventure, science, big-ass sharks

Carthago is about a lot of things but a lot of it is about the discovery of a shark big enough to cleanly chomp through a blue whale at a single pass. There might even be a plurality of such sharks.

More broadly, the book is about changes on the earth and the perhaps incremental return of great creatures. There is a yeti hunt. Liopluridon. Other thingies.

The narrative skips between several characters and a ton of time periods and locations. It's complicated and awesome and there's a TON going on. Also, the main character's daughter can maybe breath underwater. It's kind of like a super-adventure version of Children Of The Sea where tons of people get eaten.

Seriously. The body count due to sharks is probably even higher than the body count due to humans. CHOMP CHOMP CHOMP.

The book ends with a fair amount of resolution but it looks like there is more Carthago in the works. So that's cool.

On A Sunbeam

by Tillie Walden

online

Read it here

Genre notes: scifi, school, coming of age, everybody is a woman

As of this writing, 15 chapters (out of 20) of Walden's story are available and thus far they are breath-takingly beautiful. Light and darkness play against gorgeous spacey vistas, presenting the empty threat of making too miniscule the human drama unfolding in the foreground—because, really, what can matter in the face of the cosmic. Walden's answer is grandiose: the mundane daily life of a girl. And to misappropriate Walter Simonson: it is answer enough.

Walden bounces aroung through space and time to build her characters' story, relationship, and world—in much a similar way to Evan Dahm with Vattu. Only her place and time cues are a bit more over. It can be envigourating, the way Walden lets one story inform another and vice versa. And throughout, there's this sense of quiet danger, of foreboding. Everytime I read a new chapter, I'm nearly overcome by a creeping anxiety. Like THIS is the chapter where it all goes wrong.

And on top of all of it, we have Walden's illustrations. Stunning work.

1–1011–2021–3031–4041–5051–6061–75

MetricsExclusions 1Exclusions 2Navel Gazing

Goodnight Punpun

by Inio Asano

4+ vols

ISBN: 1421586207 (Amazon)

Genre notes: bildungsroman, horror

Punpun might actually be one of the most repellant protagonists I've encountered in a book. He makes me deeply uncomfortable. Goodnight Punpun is some seriously savage reading:

Honestly, Asano is an amazing creator and he's pushing the envelope on how the form is used, but I kind of don't enjoy the book at all. (Enjoy is probably not the right word.) It's very Good and possibly even Great, but I'm so distant from walking in similar shoes from pretty much any of these characters and my distaste for most of them is so strong that I don't get any of the normal satisfaction I would get reading a Good book about people who gross me out.

I'm completely onboard for picking up each volume as they come out to finish it off and see what Asano does, but I find the story unnerving enough that I probably won't read it again unless by the end Asano does something incredible that makes me feel the story deserves a close kind of note-taking read.

Maybe I'm too tame but I very much prefer A Girl On The Shore, Solanin, and What A Wonderful World to Punpun—at this point at any rate, and I can only imagine it gets worse from here). (Incidentally, 2014's Nijigahara Holographic was a beautifully drawn trash heap.)

One thing I do love is Asano's overt insertion of himself into the story as a capricious God who instigates ever-increasing traumatic events in Punpun's life, cascading his woes while prodding him and jesting at his weakness (a weakness that Asano himself writes into Punpun). As if Asano is taking direct responsibility (something Philip Pullman should have done to rescue His Dark Materials from being coquettish folderol) in an otherwise deft exercise in hyper-realism for the deep-dive into melodrama that often marks the stories and pericopes that Punpun focuses on. I think even if this alone were the sole redeeming value in the book that Goodnight Punpun would still be a work of genius experimentation. But Goodnight Punpun is thus far so much more than that.

Panther

by Brecht Evans

120 pages

ISBN: 1770462260 (Amazon)

Genre notes: childhood, imagination, horror

Panther is a weird sort of recommendation because I'm not sure I actually liked it much. It's dark and a little abstruse ( enough that I've read a lot of people misinterpret Panther to be a twisted representation of a sexually abusive father—which is not a spoiler because it's not a very well-proposed interpretation despite being very common). It's hard to know what exactly happened unless you're willing to just take everything literally. And that Panther's dialogue is all in green cursive makes it actually annoying to read, because cursive is actually annoying to read.

On the other hand, it's fiercely imaginative and beautifully drawn. Brecht's art is lush and fascinating. Panther changes his clothing and form in every panel as he engages in wordplay and play play with Christine. The book is ripe for thoughtful interpretation (though I'm not certain Evans actually gives us enough hooks by which we might come to realistically grasp what's going on).

Panther is a book to be taken in and considered. Even if you don't end up enjoying it (it made me uncomfortable, rightly).

Love In Vain: Robert Johnson, 1911–1938

by J.M. Dupont and Mezzo

72 pages

ISBN: B01MF5M0NJ (Amazon)

Genre notes: blues, biography

There's a dark magic in this book. It's illustrations, black and white, evoke woodcuts. The story is sinister and bold and relates the life and music and story of Robert Johnson, that kid who may or may not have sold his soul to a traveling devil at the Crossroads of Here and There.

I don't know how many details are available to fill out the holes in Johnson's biography but in this case it doesn't really matter. The telling is sparse but man does this project sing. I'm really taken with it, far more so than I'd expected when I picked it up on a whim. Simply beautiful illustrations.

Rolling Blackouts

by Sarah Glidden

304 pages

ISBN: 1770462554 (Amazon)

Genre notes: journalism, memoir

I was hesitant to pick up Rolling Blackouts. You'll get tired of me saying this about entries here, I promise. But I'm growing increasingly disinterested in memoir comics. There's a disproportionate number of comics in the memoir/autobio scene when compared to the value of the lives self-unveiled there. After the '90s, it seemed like autobio was the go-to genre for young cartoonists. And one of the major struggles for young cartoonists is they don't actually usually have interesting lives. There are exceptions, sure. But for the most part, they haven't lived interesting lives because they haven't actually lived long enough for their lives to accrue interest. And it's not like it's their fault or anything. Time is really just kind of a slow mover.

And that's only a piece of the trouble. One of the biggest hurdles of autobiography and memoir is that by virtue of the author’s life not being complete, the character portrayed must be a fiction. The author’s avatar is a fiction because the author, not having a perspective outside himself, has not really the ability to determine plot and direction and who his character actually is or will be. Because a reader is primarily prompted to read biographical non-fiction for its interaction with real life and real events (ignoring wholly the more philosophical question of whether there really is such a thing as Real Events), the story loses its most powerful draw by fictionalizing its subject. Removing true character arcing in this manner usually guts the biograph of its luster, turning the youthful memoir into a singular evidence of the author’s arrogance—a twenty-year-old man who tells you where his story is headed is full-up on the kind of hubris that pretends that we are the masters of our destinies’ directions.

SO, for the most part, a memoir comic needs to have something bang-up more than just the story of What Happened. Take Blankets for instance. Boy loves God, Boy love Girl, Boy loses Girl, Boy loses God isn't exactly a riveting concept. In fact it's something that pretty much most people can relate to. The finding and losing of love and the finding and losing of faith aren't in any way novel stories. They're pretty old hat, pretty tired. But somehow, Blankets invokes something beyond, something perhaps sacred. Through Thompson's unique art and framing, his story becomes more than it is.

That happens rarely. I can think of few comics that pull it off. Blue Pills is one. Fun Home somewhat succeeds through its exploration of literary metaphor. There are a handful of others. But anyway: I didn't feel confident in Rolling Blackouts. I didn't have any ill feeling toward How To Understand Israel, but it was a story we're familiar with and Glidden didn't reach for new ground in its telling. But happily, Glidden threw a change-up with Rolling Blackouts. Instead of being memoir, it aims more toward journalistic comics. It's still in the land of autobio at the outskirts, but the book is much less about Glidden and more about ruminating over the nature of things. The nature of journalism, the nature of being an American, the nature of talking about your friends. It was an interesting hybrid and it was worth my time.

The Return Of The Honey Buzzard

by Aimée de Jongh

160 pages

ISBN: 1910593168 (Amazon)

Genre notes: bookstores, suicide, regret

De Jongh, loosely inspired by Lord Of The Flies (such that two main characters are named Simon and Ralf), weaves together a story of a bookseller-by-duty has to re-evaluate his guilt over an experience in his youth.

Simon is trying not to sell his father's bookshop to a chain but is being buried in debt by not selling. He never even wanted to run the shop but feels he owes it to his father's memory. His wife is trying to be understanding, but they're going broke. Simon runs into a pretty college student who needs book-help and that begins part of his journey. He witnesses a middle-aged woman stand on the tracks and wait a couple minutes to be killed by a train and does nothing but call to her. He remembers his childhood with a bullied friend in elementary school

Shame, responsibility, hope, culpability, imagination.

And along the way, he talks about the strange nature of the honey buzzard. It's De Jongh's first published graphic novel in the US and proves the Dutch woman a talent to watch. Her art reminds of Nate Powell's. Lovely work.

How To Talk To Girls At Parties

by Gabriel Ba and Fabio Moon (adapting Neil Gaiman)

64 pages

ISBN: 1616559551 (Amazon)

Genre notes: nostlagia, slice-of-life

HTTTGAP is gorgeously illustrated and is an adaptation of a Neil Gaiman short story. It's basically this guy talking about a night he had at a party 30 years earlier as indicative of how tough a time he had talking with the opposite sex. His narration portrays them as alien creatures, lighting upon the earth as a kind of vacation from their celestial travels. It's amusing. Some people have read the story and interpreted in some sort of twist where the girls being talked to at parties are not actually human girls. I would encourage the reader away from these interpretations because they are meritless. (!!)

You know what, skip to the next entry if you haven't read the book and are averse to spoilers (even though it's not the kind of book that can really be spoiled).

The point of the story is to show how alien girls are to this kid. He doesn't understand them or how to talk to them, but he realizes this so that's why even though they're telling him all this crazy stuff, he doesn't bat an eye. The neat thing about the story is that aurally and visually, everything points to the girls being aliens but all that is just to help the narrator explain how he felt about girls 30 years ago. The idea of the story isn't that they *are* aliens but that they might as well be aliens.

That reading was basically the only way the story worked for me.

- There didn't seem to be any other reason to reveal the alien nature of the girls in the very first conversation save to later turn that on its heads.

- There didn't seem to be any other explanation for why narrator was so completely cool with them being aliens.

- This is a guy thirty years later telling a story and making something mundane seem fantastic; he's heightening all the right elements apocalyptically to underscore his thesis.

- It's a much much much more interesting story if the girls are normal human girls and it's just the telling of the story that makes them into aliens. Much more thematically rich.

- If the girls are just girls, everything becomes relateable. If they're aliens, everything is unconnected to reality and especially Vic's terror and flight doesn't really matter at all.

Mighty Jack

by Ben Hatke

208 pages

ISBN: 1626722641 (Amazon)

Genre notes: adventure, adaptation

One of my favourite books to recommend younger readers (from Kindergarten to about fourth or fifth grade) is Ben Hatke's Zita the Space Girl. It's a buoyant story about a plucky, wonderful, and sometimes not very kind little girl who gets sucked into a tremendous space adventure. Hatke wrapped the trilogy a few years back and I've been waiting for his next major work since then. He's switched things up a bit, doing a couple picture books and a shorter graphic novel (Little Robot) that's probably aimed at readers a little younger than Zita was. This year though, he brought us Mighty Jack, a sort of riff on Jack And The Bean Stalk. And you know what? It's better than Zita.

Mighty Jack proves that practice can make you better at what you do. Really, we already saw this at work with Hatke, since each volume of Zita was more accomplished than the one before. Mighty Jack is well-paced and lither. It's a fun and dangerous adventure, aimed probably at the same range as Zita, maybe a touch older. My only regret is that this first vol ends on a cliffhanger when all I really want is to plough through to the end. And yeah, I say the book is aimed at young readers, but despite the fact that my kids love it, I'm the one who is salivating to find out What Happens Next.

Hilda And The Stone Forest

by Luke Pearson

230 pages

ISBN: 1909263745 (Amazon)

Genre notes: adventure, fantasy

If you've read Hilda, you know exactly what you're getting here. More Hilda and more of her kind of adventures. The Stone Forest delivers exactly what you expect: it brings home yet one more perfectly executed stories about Hilda. If you haven't liked past Hilda, this is not going to change your mind. If you haven't read and Hilda, give Hilda And The Troll a shot and see if it's your bag. But you're good stuff, so it probably is your bag! And if you've read one or more of the others, then you have no need to be reading this entry because you're wasting time you could be spending reading this book.

Wandering Island

by Kenji Tsuruta

200 pages

ISBN: 1506700799 (Amazon)

Genre notes: adventure, coastal life

This book's cover is truth in advertising in a way. Wandering Island defintiely features both a) a perhaps-too-lanky young woman in a bikini and b) her aeroplane. It's definitely about much more (otherwise it wouldn't have made this list), but the bikini woman and the plane are both inescapable.

Wandering Island feels kind of like an adaptation of Miyazaki's Castle In The Sky. Mikura Amelia is a letter-carrying pilot in a chain of hundreds of small islands off the Pacific-facing coast of Japan. She loses her grandfather but discovers his quest to find Electric Island, an apparently mobile island city. Wandering Island is about loss, obsession, and finding a purpose. There's also a cat. And Tsuruta's illustrations are lovely and remind me a bit of Daisuke Igarashi's.

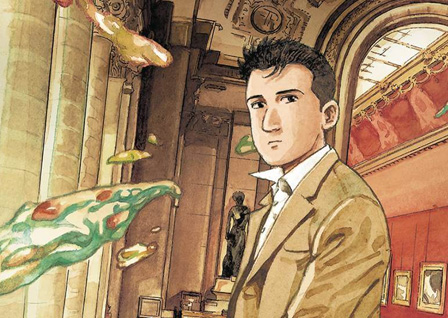

Guardians Of The Louvre

by Jiro Taniguchi

136 pages

ISBN: 1681120348 (Amazon)

Genre notes: art history

I first read Guardians Of The Louvre in June, while in a pool in Palm Springs on a vacation. I felt let down a bit. It was a good book and I was moved by its final 3/5, but after The Walking Man and The Summit Of The Gods—well, that can be a tough act to follow.

Then I read it again today, less than a week after Taniguchi's death. And I don't know if it's my tempered expectations or this reading's proximity to Taniguchi's departure from this plane, but I found the book quite affecting. At the least—at the very least—the book is a celebration of art. But since art is never just art, Guardians Of The Louvre comes off still more as a celebration of life.

1–1011–2021–3031–4041–5051–6061–75

MetricsExclusions 1Exclusions 2Navel Gazing

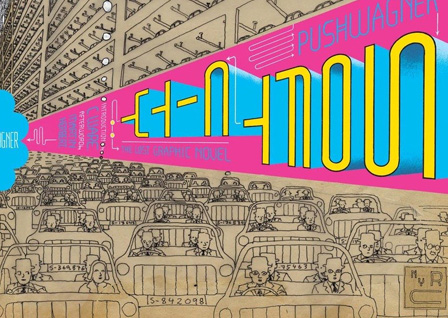

Soft City

by Hariton Pushwagner

160 pages