This list originates from a discussion I had with friends on Facebook. I came up with an off-the-top-of-my-head list of ten essential graphic novels to get a new reader invested in the dynamic range of the medium. About ten seconds later, I realized that all those books were created primarily by men. Black men, white men, Asian men—but still men. It was a good list and I stand by it, whatever it included. But that got me thinking about all the worthwhile and great comics created by women. And so I thought I'd celebrate those by sharing my Top 75. (I'll probably expand this to 100 when I have more time.)

For the sake of whatever, I've hinged eligibility on two options. 1) Primary writing credit belongs to a woman, or 2) Primary art credit belongs to a woman. Which means I won't be considering colorists, letterers, assistants, or editors. This is not to downplay their value to the final product. (Example: Walt Simonson's Thor is distinctly elevated by Christine Scheele's colours on the book, most noticeble in the recent non-Scheele recolouring—but we still consider it Walt Simonson's Thor.) This is partially a factor of the primary direction of a book being governed by its lead writer and lead artist, and partially due to the fact that if I had to research all the female inkers, colourists, letterers, assistants, and editors, I would never actually get around to making a list. (Seriously, you get into Japanese comics and researching assistants on books and you're neck-deep in an impossible swamp.)

The other thing to remember is that this list can only include books that I've read. Did I include Gabrielle Bell's The Voyeurs or Lynda Barry's One Hundred Demons? I did not because I've yet to read them. Additionally, if you don't see a favourite book listed, either I didn't read it or I have different tastes from you :) While it's fine if this makes you mad, maybe instead take this as an opportunity to celebrate there being 75 other great books out there in addition to your personal favourite. That's really a lovely position to be in!

No One Is Safe

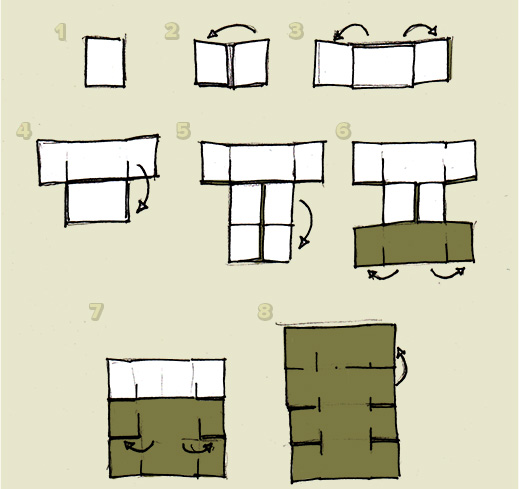

by Katherine Wirick

one 5' x 5' page

Check it out here

Genre notes: history, non-fiction, illness, autobio

Full review

This was, for a long time, going to be my Number 2 entry on the list. But then I reread it. It's been three years since I last read it. And man, there's no question for me that this had to jump up to Number 1. No question at all.

No One Is Safe is an emotional work building its pathos on several foundations. It doesn’t as violently tear at one’s heart as, say, Twin Spica does, but in being modeled on real life, its agonies seem more present—even if of a more quiet variety. Wirick investigates the Kent State shooting, her father’s relationship to the Kent State shooting, and her own relationship to an ailing father. Her investment seems total. There are moments when the project looks as if it may be too much for her to bear. The reader knows this because as an interruptive narrator, she tells us as much; but these parentheticals, these hiccoughs, are not missteps in her narrative—indeed, the four or five panels in which she breaks from script and invites us into her experience of pain are some of the work’s defining moments. Not only are they abrupt breaks in the narrative chain, but they visually take a step away from the project’s principal conceit.

Wirick’s tremendous five-by-five-foot grid is composed of over 150 separate pieces of paper. They are painted on, drawn on, in such a way as to resemble the photographs we may remember from the ‘60s—black and white with a quarter-inch of white border. These are fastened to her canvas with those little adhesive corner mounts that were common in all the best photo albums when I was four. Wirick’s three stories unfold and untangle and retangle across these “photographs” in a manner that is at once both practiced-and-careful and comfortably fluid. She appears in this work a confident author whose work deserves whatever attention you will afford it. And then she breaks her rules spectacularly.

Irmina

by Barbara Yelin

288 pages

ISBN: 1910593109 (Amazon)

Genre notes: history, war at home, romance

The fact of Nazi Germany haunts the 20th century (and even still the 21st century) like a particularly strident and pernicious spectre. How? How! How on earth could Nazi Germany have been allowed, been encouraged?

A few years back Barbara Yelin discovered a box of her grandmother's letters and diaries. From that box grew the story of Irmina, a young woman who in 1934 was living abroad in London, gaining skills and forging a path for a future in which she could grab anything she wanted for herself as well as any man could. She is of course young and with youth comes naivete, willfulness, self-righteousness, and a colossal kind of self-centered ignorance. Still, how could that young woman of raucous attitude and vivacious heart be tens years later passively complicit in the Nazi machine, buying into (to some degree at least) the promise of volksgemeinschaft?

How could a young German post-suffragette proto-feminist go from being fiercely, desperately in love with a black man from Barbados and openly mocking Herr Hitler in the streets to working in the Reichskriegsministerium and chiding non-gung-ho friends with threats of reporting? From 1934 and though 1945 and then to 1983, Irmina paints a portrait, not just of a particular woman through the global scene of the 20th century, but really of how these vast shifts of paradigm are acquiesced to and adopted by the "ordinary" citizen.

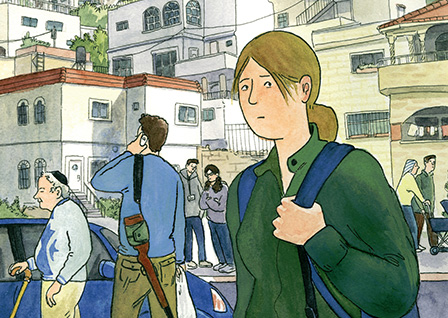

The Property

by Rutu Modan

232 pages

ISBN: 1770461159 (Amazon)

Genre notes: Drama, romance, post-war

Full review

Ruto Modan’s The Property, for all the many things it is, most interested me in its exploration of both of Linklater's earlier Before movies’ themes through its two female protagonists, grandmother Regina and granddaughter Mica. Modan almost certainly does not actively seek to explore the two films—she may not even be aware of them—but the nature of her characters and their stories puts the Linklater films strongly in mind. The titular property is never quite MacGuffin, but it may be close enough. Whatever the case, the property in question gets twenty-something Mica to visit Warsaw with her grandmother, where she meets a young man. A probably nice young man. The property also gets almost-ninety-year-old Regina to visit the city for the first time since fleeing (while pregnant) under the shadow of the Reich. It’s a visit haunted by memories of the lover she left behind. The property does have its place in both motivating story elements and drawing things to their open-ended conclusion, but this is a story of persons interlocking and intertwining rather than any sort of real-estate thriller.

And while Modan crafts an entirely enjoyable story for the younger Mica, it’s in Regina’s life and reaction to Warsaw that The Property was most fascinating to me. Jesse and Celine probe their frustrations and disappointments in Before Sunset, considering what might have been and how time both dissolves what was and erects new burdens (as well as mythologies)—but they’re still young and only what, thirty-one? Regina interacts similarly in her own homecoming—only where Jesse and Celine have decades of potential joys and mistakes ahead of them, Regina at nearly ninety has little time left. She may be spry enough to travel, but illness lurks and too often our elderly are taken by nothing more powerful than the common flu. And that pointed fragility makes a vast difference in the way one will regard their dreams and their future. (An abiding and important theme throughout is Warsaw-as-cemetery. It’s on the book’s cover. It’s mentioned in the opening pages, and the climax takes place in the grand and sprawling cemetery.)

In Clothes Called Fat

by Moyoco Anno

264 pages

ISBN: 1939130433 (Amazon)

Genre notes: cultural critique

Full review

Moyoco Anno’s In Clothes Called Fat intimately concerns a world maintained and partly governed by the sexual objectification of women and reads as a good companion to Kyoko Okazaki’s Helter Skelter. The book revolves wholly around how the principal identity of a woman is founded in her attractiveness. Every new chapter (save for the finale) is abstractly heralded by the depiction of a lean, beautiful, and often nude woman—who is not (until the last chapter) the protagonist. The entire ecosystem of Anno’s story is populated by an ethos and ethic developed around the desirability of women.

Anno delves into the experience and mystery of the culture’s fascination with beauty through unsparing episodes from Noko’s life. Her sex life, the bullying she experiences at work, her abortive attempts at self control. Noko is victimized by her own lack of self-confidence and inability to truly grasp the manner of the world about her. A dietician describes Noko: “Her soul is obese.” Anno allows the reader to dwell in Noko’s thoughts, giving us insight enough into the protagonist’s sense of the world and herself.

The principle conflict seems to be the question of whether Noko will be able to lose weight, thereby gaining confidence and a place in society, but Anno is canny enough to avoid a problem/solution pairing so pedestrian. Instead, In Clothes Called Fat wonders if it really is the clothes that make the man, postulating instead that no woman can successfully survive the ravaging of society and escape with her true self intact.

Russian Olive To Red King

by Kathryn Immonen

176 pages

ISBN: 1935233343 (Amazon)

Genre notes: ghost story, wilderness survival, loss

Full review

In Russian Olive To Red King, we have this magnificent admixture of craft, colour, tone, and experiment that helps nudge the seams of the comics package in exciting ways. It's not perfect and I have quibbles, but it really is lovely and tells a compelling story. Kathryn Immonen's script is well-devised and the essay she closes out the book with both fits the tone ans reads as the literary non-ficiton work the male lead might be known for. Stuart Immonen's illustration is some of the best of his I've ever seen and the colouring is at all points perfect.

It's a curious book. Part ghost story, part love story, part essay about an elephant. It's experimentalist and it makes you work for its value, but it's very well done and strikingly gorgeous - and I always like to see the Immonens working together on books.

Helter Sketler

by Kyoko Okazaki

320 pages

ISBN: 1935654837 (Amazon)

Genre notes: culture critique

Full review

Helter Skelter tells a tale reminiscent of Sunset Boulevard (and even straight-up references the Billy Wilder film) and prescient of Moyoco Anno’s Sakuran. Actually, it probably plays avatar for the million other stories about women whose usefulness is predicated on their sexual beauty and the desperation with which they fear the abolition of such a temporary celebrity. Not only do such heroes of the popular culture have to contend with the constant fickleness of a populace whose tastes bend and twist on a dime, but terror of the inconstancy of the masses is bolstered by the model’s knowledge that age weathers all and that she only ever had a dwindling, minuscule shelf-life. In Liliko’s case, her terror is accelerated by a brute fact of the procedures she used to mold her body into a physical perfection—while drugs and treatments may temporarily slow the degradation, her flesh will begin eroding at a terrifying rate. And more than just aging dramatically, women who’ve undergone similar treatments show seeping lesions, deep bruises, and corrosion of the material beneath the flesh. These women become monsters, and monstrosity is Liliko’s certain future—so she’ll see if she can’t get a jump start on it.

It’s a lunatic ride.

Exit Wounds

by Rutu Modan

168 pages

ISBN: 1897299834 (Amazon)

Genre notes: romance, terrorism

Modan's story about a Tel Aviv guy trying to find out if his philandering father died in a bombing in Hadera while traveling around interview people with his dad's 20-something-year-old girlfriend is simultaneously mystery and coming-of-age extravaganza. Who is the father? Who is the son? What does it all mean? Sounds pretentious maybe, but it's lifelike and well-wrought.

Sacred Heart

by Liz Suburbia

312 pages

ISBN: 1606998412 (Amazon)

Genre notes: teens, rapture cults, music

Sacred Heart was phenomenal. It was like reading Roberto Bolaño fish together a comic about American teenagers and rapture cults. It was chaotic and haunted and full of life. It's a brutal, mysterious book and really embodies the kind of visceral realism Bolaño introduces in Savage Detectives. It also carries the apocalyptic kind of vibe from 2666. Suburbia's pacing was magnificent and the slowburn of discovering what is actually happening is delectable. I loved the way she would sometimes punctuate each cell of a montage with onomatopoeia.

Suburbia's illustration of music was so so so much better than anything else I've seen in the field. Scott Pilgrim has this sort of wobbly ghost electricity rising like incense from the instruments and that's okay. Jem has these crisp, sterile pink streams that swirl around and ghost through everything, but it always feels electric but soulless. (Which is fine because Jem always feels like corporate pop to me.) In Sacred Heart music has this physicality. It bombards and punches and people get swept up in it and get out of its way.

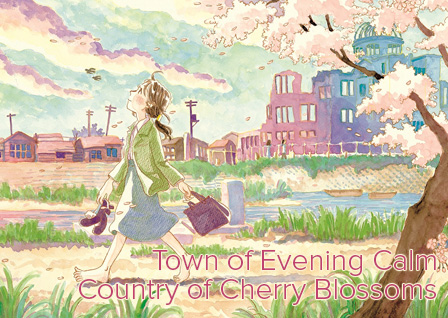

Town Of Evening Calm, Country Of Cherry Blossoms

by Fumiyo Kono

104 pages

ISBN: 0867196653 (Amazon)

Genre notes: war, post-war, romance

Full review

Kouno crafts a story that is at once full of so many of the facets of our nature that it can be breathtaking to see how flawlessly they’re brought to life in such a short span of pages. Greed, fear, guilt, shame, anger, regret, sorrow, love, laughter, hope, song, and joy. All of these features of the human frame are present in Kouno’s two-part story. Still more, we see the insidious hand of history and the buoyant touch of nostalgia at work throughout the book’s narrative.

Kouno’s book is divided into two related stories: “Town of Evening Calm” and “Country of Cherry Blossoms.” Hence the terrible title for the book as a whole. Each explores the lives of members of a single family who live as survivors of the Hiroshima bombing and struggle to find their place, being caught between a society that quietly fears them and the weight of survivor’s guilt. Alternately heart-warming and gut-wrenching, this brief exploration of the civilian impact of modern warfare is as good as anything I’ve encountered on the subject. Kouno is neither gratuitous nor melodramatic and her simple stories are powerful reminders of both the heroic and villainous ends of the human spectrum.

While Kouno homes her storytelling lens on the individual—a young woman (in the first part) who struggles to accept the possibility of love in the wake of her unfair escape of Hiroshima’s destruction and (in the second part) her brother and his children’s firsthand experience of the unspoken apprehension felt by a society that would not or could not allow themselves to empathize with hibakusha (surviving victims of the Bomb)—her purpose spans much wider territory. She, in fact, aims to confront the human being in its peculiar existence as seat to both horror and beauty. And even while condemning the race, she hints at the wonder of humanity and the good that it can accomplish when it doesn’t allow its nature to get in the way.

This One Summer

by Mariko Tamaki and Jillian Tamaki

320 pages

ISBN: 1626720940 (Amazon)

Genre notes: coming-of-age

Full review

This One Summer contains masterful writing and masterful illustration certainly, but what does it convey? If, as I suspect, all stories are nostalgic, then what makes this particular story unique? If this is not to be read as some basking in the golden glow of our long-forgotten and longer-remembered youths, then what are the two Tamakis circling here? Why do they wish to remind us of what happened this one summer?

While their answer might be (and probably would be) far different from my own, I think it essential to recognize This One Summer as an exploration of family, especially through the several women of varying ages who fill the story’s corners. At the center, of course, is Rose—a woman at the cusp, so to speak, of womanhood. She’s about thirteen and is that kind of bundled nerves, ideas, and curiosities that seem to almost universally mark the early teenage experience. She’s ignorant of a lot and wonders about sex, feeling some of the stomach-churning pull that physical attraction can hold for the uninitiated. Simultaneously, she’s protected by that kind of uncompassionate sociopathy that allows one human to hold no empathy for the concerns of others. When a local girl becomes accidentally pregnant by her local boyfriend who does his level best to abandon her via passive aggression, Rose cannot sympathize. The girl, to Rose, is simply a “slut”—and whatever that actually means, she is therefore unworthy of compassion. Rose’s mother is plagued by a particular and acute tragedy, driven into depression and a colourless fatigue. And Rose’s reaction is to feel affronted and personally embittered. And yet there is a hope for Rose because by This One Summer's insistence in portraying women at all ages, we are driven to see that Rose is on a path rather than a fixed point. This One Summer is not her story. It is, instead, one of her stories. It is the smallest part of her story. It’s simply something that happened this one summer when she was not yet an adult and not quite any longer a kid.

Beauty

by Kerascoet

144 pages

ISBN: 1561638943 (Amazon)

Genre notes: faery tale, culture critique

I wasn't sure about Beauty for perhaps its first half. It felt very much as if it were intending to be just a cliched cruel faery tale, a moral lesson about being careful of what one wishes for. (And I suppose that's there to some extent.) But after everything goes rotten and continues to go rotten and new rotten things are introduced, somewhere in all that the tenor begins to change and life forces begin to assert themselves and beauty becomes a thing much better than it might have been.

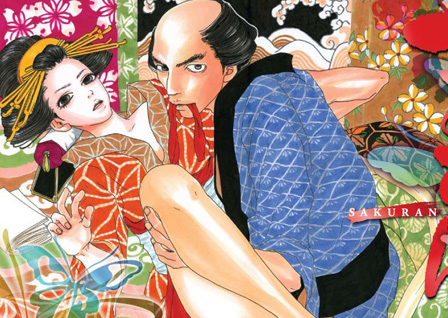

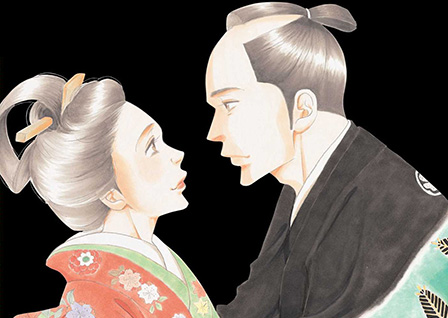

Sakuran: Blossoms Wild

by Moyoco Anno

308 pages

ISBN: 1935654454 (Amazon)

Genre notes: historical

Full review

When I approach a book like Sakuran, the experience is emotional for me. Moyoco Anno’s book is about women in distressing circumstances, and throughout I felt the weight of the whole history that has arrayed itself against the female existence. I think of my wife, my daughter, my mother, my friends, women I know from the internet, and women I don’t know at all and will never know. Societies over the long centuries and societies in this very moment have not made living the kindest of experiences for women—societies governed and purposed by my people, by men. I hate us for these inequities and a book like Sakuran fills me with tidal waves of regret and sadness, even if that is not its purpose. Moyoco Anno’s Sakuran concerns Kiyoha, an 18th-century courtesan who is destined (by Anno’s pen) to become the most celebrated of all the houses in Yoshiwara. Anno begins by introducing Kiyoha as she nears the height of her fame and then peels back for the rest of the book to chart the woman’s course across what turns out to be a hard and bitter sea. Kiyoha is a “strong” female character in the sense that she survives to better herself through her experiences; but simultaneously, she is not immune to her circumstances and her life of prostitution under contract to her house takes evident toll on her. She realizes the world she’s trapped by is terrible and makes the best of it, but she never shies away from acknowledging the reality that her role as courtesan is dominated by paternal influences.

I have it on pretty good authority that “sakuran” refers to confusion or derangement or mental agitation. The book’s subtitle Blossoms Wild, as well as an apt description of the madness of Kiyoha’s blooming sexuality under such a terrifying commodification of the female self, seems pretty probably a play on the homophony between sakuran and sakura, the Japanese term for cherry blossoms. Kiyoha’s maturing and sexual bloom within the walls of the pleasure house is agitating for the character as well as for the reader. It seems trite to compare our distress to hers, but it’s Anno’s implication of the reader into the intimacies of Kiyoha’s decade of depetaling that provokes the reader to empathize with Kiyoha’s state—even if to a lesser degree. (I recognize the preciousness of describing a woman’s initiation into coupled sexual experiences as “deflowering,” but Anno almost pushes the description by her title. As well, the coercive nature of Kiyoha’s sexual engagements are rapacious and demanding and strip her of any of the tenderness we treasure in the potential warmth of the sexual act.)

Dotter Of Her Father's Eyes

by Mary M. Talbot

89 pages

ISBN: 1595828508 (Amazon)

Genre notes: biography, autobio, social issues

Full review

In this both biographical and autobiographical work, Mary Talbot (aided visually by husband and illustrator Bryan Talbot) confronts the struggle of society to lurch into the era of modernity and beyond. It’s unclear whose story Talbot is more interested in (or if she even has a preference), but she introduces an inclusio whereby she in the current day finds an old ID card belonging to her now-deceased father. Inside the framing device Talbot pursues two narratives: one concerning her own formative years at the hand of her father James Atherton, a well-regarded Joycean scholar, and the other charting the development of James Joyce’s own daughter Lucia and the relationship he had with her. Neither relationship is a thing of joy and beauty, but one suspects that if both girls were born to the same fathers a century later, the absence of certain social constriction might have allowed for happy endings all the way around.

As delineated by Talbot, both Mary’s and Lucia’s lives are welled up under the pervasive irony of being the children of bastions of modernism who cannot see clear to apply modernist principles to their own patriarchal relationships. Dotter lays special emphasis on the rallying cry of the paradigm movement: “How modern!” Everyone around both Mary and Lucia are caught up in the transformation of culture—of the evolution of the stilted, errant, grossly conservative pre-modern society into the glorious fortress of progressive social democracy found in the modern utopia. It’s a period of hope and change. And each of these two fathers are in some sense heralds or ambassadors or representatives of this new civilization.

The irony of course is that in the cold darkness of their hearts’ hearts, they are still staunch defenders of the Old Ways—hopeless, helpless relics who will unconsciously stop at nothing to crush the Spirit of the Age in its most immediately tangible bastion. They will carelessly destroy their children (or perhaps die trying), unaware that in so doing they make mockery of those values they pretend to hold dearest to their hearts. Mary’s father Atherton will do so by his direct actions built of disdain and outright dismissiveness of his daughter. Joyce, on the other hand, will combat his own values through a negligence in policing he and his wife’s failure to recognize Lucia as something more than their provincial understanding of the female being will allow.

“Sad life. Sad life,” to quote a certain wise but immolated horse.

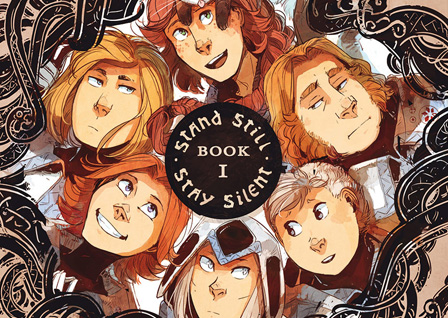

Stand Still Stay Silent

by Mina Sundberg

323+ pages

Purchase from Hivemill

Genre notes: post-apocalypse, zombies

Post-apocalyptic zombie fiction has never been better. Which is good because the post-apocalypse is pretty well played out and man do I hate zombie fiction. But Sundberg's vision here is almost entirely unique in every way.

1) The remaining civilized world is so far limited to Iceland, fortified pockets of Norway, Sweden, and Finland, and a single island of Denmark. That's a rare and interesting setting for a story told in English.

2) The zombies aren't zombies like we typically think of zombies. There're also corrupted beasts and now, apparently, ghosts (?). The lore of this new world is extensive, detailed, and imaginative.

3) Sundberg's art is gorgeous. It's luscious and the way she affects mood through colour is essentially like nothing I've seen.

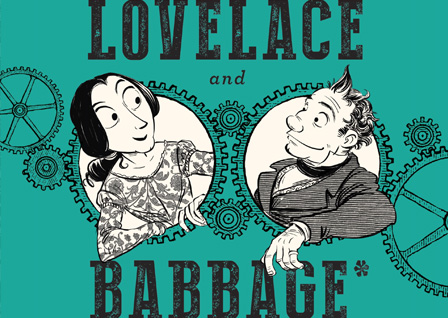

The Thrilling Adventures Of Lovelace And Babbage

by Sydney Padua

320 pages

ISBN: 0307908275 (Amazon)

Genre notes: biography, alt-history

Thing 1: Ada Lovelace was pretty badass and her story is more fascinating than a lot of stories.

Thing 2: The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage is an exciting book about a lot of really boring subjects.

There's a lot of math and engineering and economic theory that form the bedrock of this book, but Padua approaches it in inventive and humourous ways. I'm sure people who actually have an interest in those subjects will be over the moon for this book, but for the rest of us, Padua still crafts something interesting and informative and funny and crisp. And her footnotes are nearly as interesting as those that inhabit Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrel.

5 Centimeters Per Second

by Yukiko Seike

566 pages

ISBN: 1932234969 (Amazon)

Genre notes: romance, coming-of-age

Full review

With all of her additions, Seike’s adaptation of the film 5 Centimeters Per Second strikes an entirely different vibe from the film and its tonal difference is dramatic. While Seike doesn’t obliterate Shinkai’s original conclusion, she does offer something more satisfying (at least to Western readers who delight in loose ends being tied and clipped). I am one of those who appreciated what I imagined Shinkai to be saying with his mostly downbeat conclusion. I thought his ending was natural to the story he was telling. (Caveat: I was also fine with the conclusion of John Sayles 1999 film Limbo, whose ending was booed in my audience.) That said, Seike’s version is the more mature work and its length and heavy use of dialogue allow it to explore the implications of Shinkai’s world a bit more insightfully.

Probably because of Shinkai’s interests combined with his film’s barely-over-an-hour runtime, the original’s focus was acute. It was solely concerned with Takaki and how his inability to hold onto love dominated and destroyed his life (at least for a time). Seike’s version treats that but also explores the ramifications of Takaki’s brokenness. We are all every one of us participants in our societies and even our most internal struggles leave marks on the outside world. Our joys, fears, activities, ideologies—everything—affect those around us, even those we fail to notice. Seike’s 5 Centimeters explores that in a way that Shinkai’s was either unable or unwilling to do. And Seike’s epilogue takes Takaki’s story beyond where we previously saw it end and does so in a way that’s both true to Shinkai’s 5 Centimeters and true to the new vision, which Seike has developed.

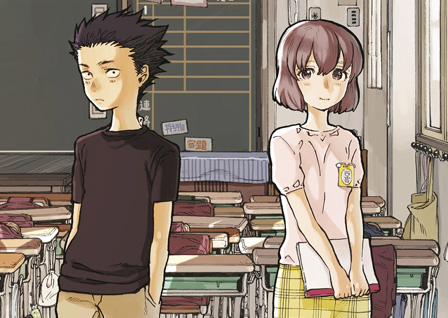

A Silent Voice

by Yoshitoki Oima

7 vols

ISBN: 163236056X (Amazon)

Genre notes: disability, bullying, romance, high school

Full review

A Silent Voice begins with the story of two kids in elementary school—Shoya the reckless, popular kid and Nishimiya the new girl, who is deaf and communicates through writing in a notebook (since nobody knows sign language). Nishimiya’s inability to hear and the problems that crop up as a result are too strange for Shoya and so, leading by example, he creates an environment in which Nishimiya is bullied daily and with extreme prejudice. She is scorned, mocked, and has her hearing aids repeatedly torn from her ears and destroyed. When it eventually becomes too much, the girl’s mother complains and all blame is pushed onto Shoya’s shoulders. From that point forward, he is systematically bullied by his former friends in a manner far more vicious than that with which he instigated against Nishimiya. His resentment against her swells, and he gets into a fistfight with the girl, prompting her mother to remove her from the school. Six years pass and Shoya endures trouble all through elementary school and junior high. Through hindsight and reflection, he finds himself reevaluating those early days, and now as a highschooler, Shoya seeks to have one final, repentant conversation with Nishimiya.

And the story moves on from there.

A Silent Voice is concerned with the transition from sociopathy (non-clinical) to empathy. Just as I had to evolve from my early-twenties experience of passive aggression, so does Shoya seek to learn how to melt from his seclusion and inability to relate to others. While the details of his path are different from my own, it’s comforting to see the generalities are not unique to myself. I don’t usually look for representations of myself in the literature I take in, but for whatever reason I appreciate it in this case. Perhaps because I know that Shoya’s story will end happily, it provokes hope for the conclusion to my own story.

As a storyteller, Oima is perfectly suited to her task of unveiling A Silent Voice’s trajectory. Her art is lovely and her framing and perspective dynamic. Her drawings convey a wealth of emotional information. Her elementary school kids look rather like children. and her highschool-aged versions of the same mature predictably, giving the reading a certain place to hang their hat. I love her art and that will probably be enough to interest me in any other projects she pursues.

A Bride's Story

by Kaoru Mori

8+ vols

ISBN: 0316180998 (Amazon)

Genre notes: history, customs, romance, adventure

Full review

A Bride’s Story offers contemporary readers a delightful opportunity to exercise the skill of reading and enjoying a text without finding moral agreement with the circumstances, actions, or particulars of its protagonists. For this reason, A Bride’s Story may even be desirable to get into the hands of younger readers (despite some occasional nudity) if for no other purpose than to promote this critical ability at an early age. Mori makes this an elementary text for this kind of exercise. Almost no American reader will approach the text thinking it good or appropriate that a grown woman should marry a boy who is only straddling the boundary between childhood and puberty—yet that is the circumstance this culture forces on its two very winning protagonists. Further, the reversal of the autumn-spring relationship trope presents opportunities to consider the contemporary sexual politic. As well, it’s interesting to see a situation in which a clearly competent, intelligent, and mature woman should still be ultimately under the authority of a child (a kind child who evidently cares deeply for his new charge, but nonetheless…).

As with Emma, Mori crafts an exciting story that keeps a reader’s interest—even while she explores all kinds of cultural nooks, crannies, etc.—but so far, the real star of the show is her artwork. Mori seems to have matured since Emma and her designs and layouts carry more interest. Atop that, she commits the biggest personal sin a cartoonist can. A Bride’s Story is, in every page, filled with highly detailed and ornamented clothing. The kind of stuff that looks ridiculously cool on a cover or poster, but isn’t the kind of thing anyone would want to draw over and over and over again. It would take me probably a day to draw a single panel that featured one of Amir’s dresses. Or a rug. Or some throwaway eaxmple of embroidery. She makes American artists who can’t keep a schedule seem like a sad, tawdry bunch.

Ooku: The Inner Chamber

by Fumi Yoshinaga

13+ vols

ISBN: 1421527472 (Amazon

Genre notes: history, alt-history, culture critique

Full review

Ooku is a work of alt-history. It posits a Japan that never happened and traverses eighty years of would-bes. Taking a page from Y: The Last Man, author Fumi Yoshinaga oppresses 17th-century Japan with a plague, called the redface pox, that decimates the male population of the nation (other countries seem unafflicted). By the time the disease has worked its course, there is only one man for every five women. The national character evolves quickly and drastically under these new terms and the roles of men and women within the society undergo sharp shifts in vocational direction. Women become the primary workforce, tending to all mercantile matters, all fieldwork, and all burdens of government—while men, now prized primarily for their reproductive function, are often sequestered and kept from any exertion that might tax their delicate constitutions. Many men are prostituted by their families to women who don’t need the sexual release so much as they simply desire offspring. The Yoshiwara pleasure district quickly empties of women and falls into disuse until it comes to play house to men dedicated to the role of stallion. For their part, women take on the role of lords of households and rulers of domains—even claiming the Shogunate as a female role. And it is with this last that Ooku is concerned.

Ingeniously, the first volume of the series introduces the situation eighty years after the plague hit, exploring this strange world through the eyes of Mizuno, a young man who enters into the service of the Shogun’s inner chamber (what is known as the Ooku). Alongside Mizuno, the reader learns of the situation of men within what I presume to be the most secretive palace in all Japan—though, to be fair, we have yet to see the Emperor or his/her own inner sanctum. The entire staff of the palace is men. The Shogun keeps for herself a stable of well over a hundred men, none of whom may ever leave the palace grounds—service in the Ooku is a lifelong duty. With Mizuno, the reader comes to understand the duties, hierarchy, and politics of the place. Nearly upon his entrance into service, the sixth Shogun dies and is succeeded by her young daughter—who also dies soon after, still a child. The succession then passes to Yoshimune, the eighth Tokugawa Shogun, and it is with her entrance that the focus of the book shifts and begins developing a host of protagonists and points of view.

On a Sunbeam

by Tillie Walden

online ongoing

Read here

Genre notes: sci-fi, coming-of-age

As of this writing, six chapters of Walden's story are available and thus far they are breath-takingly beautiful. Light and darkness play against gorgeous spacey vistas, presenting the empty threat of making too miniscule the human drama unfolding in the foreground—because, really, what can matter in the face of the cosmic. Walden's answer is grandiose: the mundane daily life of a girl. And to misappropriate Walter Simonson: it is answer enough.

Miss Don't Touch Me

by Kerascoët

192 pages

ISBN: 1561638994 (Amazon)

Genre notes: murder, brothels, thriller

Full review

Set around the turn of the 20th century, Miss Don’t Touch Me concerns two sisters (one a flirt and the other a prude), suburban dance parties, a serial killer, a brothel, and the dish best served cold. When cold, reserved Blanche becomes accidental witness to the Butcher of the Dances (the mass media is every bit as fanciful a century ago in France as it is in America today), Agatha falls victim to the killer who hopes to cover his tracks. Blanche is destroyed emotionally but this devastation prepares her for the journey of detection and subterfuge for which she’ll have to be steeled if she wants her revenge. Circumstances lead her into the employ of a brothel where her prudishness and refusal to be touched by a man lead her to become the shop’s special dominatrix. Dressed as an English maid, she whips, beats, and savages every single one of her clients, earning herself the title Miss Don’t-Touch-Me. Yet as she gets nearer to identifying the killer, she comes closer to falling into the killer’s path. It’s a treacherous road and one will wonder whether her violent loathing of men will be enough when she comes face to face with the man who killed her sister.

While Miss Don’t Touch Me’s story travels the necessary paces for every thriller—mystery, betrayal, reversals, and the big showdown—the true glory of the book is its art. I’d not yet run into Kerascoët’s work when I first read the book but I've been happy to encounter it more over the years (and in a couple other books on this list). Their characters are cartooned, with all the exaggerations of character that one might expect to see in New Yorker cartoons but with a degree of polish that makes them sing. Blanche herself is perfectly rendered and Kerascoët ably bounces her between rage and sorrow and fear and comfort and grim determination.

Ducks

by Kate Beaton

Read here

Genre notes: memoir, social issues

While Kate Beaton is largely known for her very funny comics about literature and history (notably in her collections Hark A Vagrant and Step Aside Pops) and is loved for her humourous comics about visiting her family over the holidays, my favourite of her works is Ducks, a short series that explores Beaton's time working in the Canadian oilsands (a terrible place).

The work balances really well the largescale environmental issue with the individual personal dramas that swallow everyone regardless of their exterior contexts.

It will probably take you ten minutes to read. Maybe less. It's worth that time.

Moving Pictures

by Kathryn Immonen

144 pages

ISBN: 1603090495 (Amazon)

Genre notes: drama, historical

Full review

Moving Pictures is a fantastic little book. A novella of sorts, exploring the interrogation of Ila Gardner, a young Canadian curator of third-rate art in German-occupied Paris, by Rolf Hauptmann, a member of Germany’s Military Art Commission. The Commission is tasked to retrieve famous works from the French who have squirreled the works away to prevent the theft (and possible destruction) of their art. While the single interrogation comprises the backbone of the story, the Immonens add depth and explanation via multiple brief flashbacks.

The story is well-told and exhibits its creators’ mastery over the medium. Kathryn Immonen’s script crackles with irreverent wit such that the book in many ways feels like a well-conceived adaptation of a theatrical play. The plotting is graceful, offering revelations at good intervals, neither leaning too heavily on flashback nor hashing out too much exposition in the interrogation dialogue. And beautifully, the flashbacks do not unfold chronologically.

Fun Home

by Alison Bechdel

232 pages

ISBN: 0618477942 (Amazon)

Genre notes: autobio

Full review

The first time I read Fun Home, I felt like Alison Bechdel was over-reaching, that she was just plain trying too hard. The literary allusions, while inventive, seemed forced. Her inclusion of such a wide variety of authors and themes seemed too pat, too cute. I felt she was trying to impress with the gravitas of prior works, fearful that her family’s story wasn’t strong enough to stand on its own.

I have, happily, revised that opinion substantially. Three cheers for second readings, eh?

There are still moments when I feel Bechdel is grasping for allusions beyond her ability to furnish (notably the Icarus/Daedalus opener that just doesn't work), but those instances are many fewer than I had originally felt. (Either that or my nostalgia for the book has since coloured my readings with good will and charity.) And on the whole, Bechdel’s incessant reference to the works of others doesn’t distract as much from her family’s story so much as I originally felt. Or, actually, it does but in repayment adds a more robust sense of who these people are. Their lives—at least the lives of Alison and her parents—are so thoroughly dominated by the writing and words of others that to tell their story without these grand allusions might have been to tell a hollow version of things. My second reading allowed me to appreciate more fully the depth to which Bechdel’s father was influenced by the Moderns and how substantially Alison was shaped by the writings of her own era and how those in turn influenced her readings of the others.

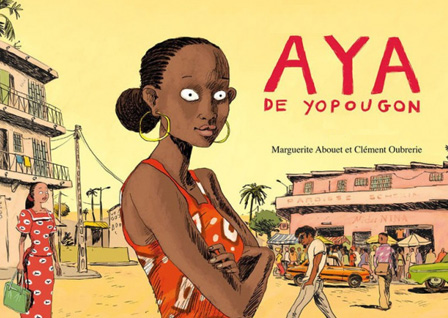

Aya

by Marguerite Abouet

2 vols

ISBN: 1770460829 (Amazon)

Genre notes: life, coming-of-age

I'm too tired and filled with pain to write about Aya right now but for to say that I found this treatment of African life delightful and joyous and tragic and wonderful and ribald and full of an unquenchable life and vigour. This series is not to be missed. The entire series is collected in Aya: Life in Yop City and Aya: Love in Yop City

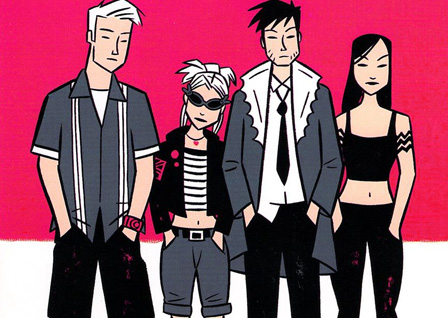

Hopeless Savages

by Jen Van Meter, Christine Norrie, and Meredith McLaren

4 vols

ISBN: 1934964484 (Amazon)

Genre notes: family, music, life, romance

Full review

Over the course of the series, Van Meter makes marked use of flashback. Every chapter contains a several-page flashback (drawn by a secondary artist so that it’s easily discernible from the main story). These flashbacks not only embellish the current storyline, giving motive to otherwise unexplainable actions, but they serve to give the series a grounding in history. It’s one thing for us to hear that Nikki Savage used to be a wild thing on stage but another to actually see what she was like back then. It’s one thing to know that Rat left the family because of a girl but another to see it play out. These bits and pieces lend credibility to the work. Kind of like how Tolkien’s inclusion of songs and legends helps the realization of his LOTR world.

One of the recurrent themes of Hopeless Savages is family and its essentiality. With the exception of Zero (who is, I believe, a junior in high school at the start of the series), all of Dirk and Nikki’s children are grown and leading their own lives (and generally pretty successfully). Dirk and Nikki are on the verge of being empty-nesters. But far from being on the cusp of a certain lonely liberation, their family is still very close and they spend more time together than many families that share a single roof. For all of the Hopeless-Savage’s anarchic roots, the governance of valuing family rules each of their hearts almost completely. It’s a joy to see—and as a father to young children, I hope to see my life somewhat a mirror to theirs twenty years from now.

Hopeless Savages is an enjoyable series and four volumes is tragically too few for characters who deserve far more. I very much hope Van Meter will eventually return to this creative corner and round out the cast a bit more. And then more. And then more.

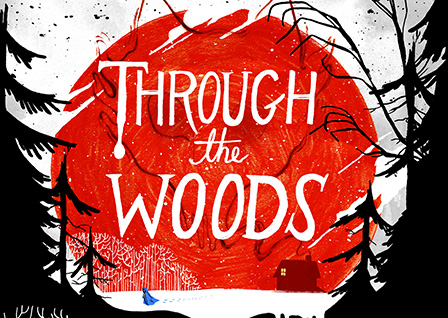

Through The Woods

by Emily Carroll

208 pages

ISBN: 1442465964 (Amazon)

Genre notes: horror

Emily Carroll is comics' crown prince of horror. I mean, if she were male. And if comics were a monarchy. And if her dad was the king of comics horror. Whatever the case, she's amazing at horror. I don't want to say she's better at it than Junji Ito, but she probably is. Hers is a more provincial kind of horror though. More mundane. The kind of stuff that would be the twisted dreams of a pre-industrial West. She's been putting out amazing horror comics for years on the internet, but someone finally had the good sense to publish her in handsome hardback.

Special note: Through the Woods contains "His Face All Red," one of my favourite of her works, which you can still read for free on the internet.

Emma

by Kaoru Mori

5 vols

ISBN: 0316302236 (Amazon)

Genre notes: drama, historical, romance

Full review

Mori’s storytelling is impressive. The weight of her line perfectly suits her subject matter; it’s crisp and confident. She excels at choosing setting, pace, and moment, giving her characters the opportunity to reflect on actions, words, or thoughts from prior panels and pages. As well, Mori includes any number of silent scenes, allowing the reader to pause and take in the full scope of what is occurring within the more introspective parts of her characters stories. Keeping the reader involved, Mori uses a number of visual devices, requiring one to pay attention to camera angles and character details. The storytelling occurs as much through visual relief as it does through verbal narrative and dialogue.

Emma is chiefly the story of Emma and William, an orphaned household maid and the son of the monied class. This is a romance and we see them meet-cute, fall for each other in that stereotypically understated Victorian way, encounter difficulties due their class distinctions, and finally resolve their relationship. It’s a lovely little story.

The Oven

by Sophie Goldstein

80 pages

ISBN: 1935233335 (Amazon)

Genre notes: dystopia, pregnancy, drug use

The Oven is a well-wrought glimpse of greener pastures and how two people can love each other and still fall apart. It's a utopian world where genetic expression is regulated and couples with bad genes cannot procreate. Eric and Syd think they want a baby, but Eric has a gene for acne so they leave civilization for a hippie commune so that they can breed it up unrestricted. Neither are sure they want this, but they want to give it a shot. It's not easy and by the time they realize that their eyes were bigger than their stomachs for this new lifestyle, it's too late to make a decision that won't destroy something they've built together. Good, simple, worthwhile.

Persepolis

by Marjane Satrapi

2 vols

ISBN: 037571457X (Amazon)

Genre notes: Iran, autobio

Persepolis would be higher on my list had I stopped reading with volume 1, which concerns Marjane as a child in a changing Iran. This section of the story is delightfully wrought as young, precocious Marjane expresses with a child's liberality her feelings about the fundamentalism that immediately swept the nation. Her guilelessness is deeply winning.

All that changes in volume 2, which concerns teenage Marjane. As with most of us in our adolesence, teenage Marjane is obnoxious and not really all that fun to be around. She's not bad for a teen but she's still a teen. I wasn't likely that fun to be around either. And so the charm of her story wears a bit thin. It's not all bad but never reaches the heights of the first volume.

Beautiful Darkness

by Kerascoët

96 pages

ISBN: 1770461299 (Amazon)

Genre notes: adventure, bildungsroman, horror

Full review

I’m going to be up front on something that concerns this comic that I really do like: I don’t understand Beautiful Darkness. I love it, but I don’t get it. Not yet at any rate. Maybe some day. When I’m older, perhaps. Or maybe later this afternoon when everything just suddenly clicks and I’m left wondering how I could have missed something so obvious. But likely, I won’t ever discover the depth of its purpose without some sizable assistance—perhaps some focused conversation with like-minded friends, hashing out details and proposing interpretations.

So then how can I justify my rating of this book? If I don’t know what it meant, or even necessarily what happened, can I reasonably tell you that you should read and enjoy this book even as I did? Perhaps not.

But all the same, I did enjoy Beautiful Darkness. I was entranced while reading. It held me rapt with its grim and lushly vibrant sense of itself. So instead of justifying why a person should enjoy Vehlmann and Kerascoët’s book, I simply talk about why I did. At least for now, while I fail to understand it.

Artistically speaking, Beautiful Darkness is a tremendous exhibition of the illustrative craft. I first encountered Kerascoët’s work in Miss Don’t Touch Me, which was lovely and wild and inspired me to pick up the present book. However grandly I felt toward Kerascoët, reading Beautiful Darkness was revelatory. They flit between cartooning and realism deftly. Their colours paint a world very much like our own. Warm, cool, sinister, cozy. Just taking a moment to flip though Beautiful Darkness infects the soul with the sense that people are amazing, that wonderful things are afoot.

Eat More Comics

by a bunch of people

300 pages

Buy here

Genre notes: Politics, social issues, life

Full review

Eat More Comics (the comic with possibly the least appealing cover of all time) is subtitled "The Best Of The Nib!" As an anthology of a variety of comics that appeared in The Nib, my wish is that the book would have been shorter and called "The Best of the Best of the Nib." Because while there are some sublime works included, there is also some plebian dog crap. Usually, it's the political cartoons that are the festering blights corrupting the value of the book. And often, I agree with the thesis of these comics. They're just so dunder-headed and lack so much nuance that they can't come close to communicating anything worthwhile. The essay comics and journalistic comics, however, are almost all fantastic. I'm glad I bought the book but I wish it could have had an editor with a wiser eye for value (or an editor with greater strength to follow their wise eye).

Among my favourites from the collection are:

- #lighten up

- A Lost Possibility: Women on Miscarriage

- San Francisco's Class War by the Numbers

- Crossing The Line

- Just a Word

- Hart Island Hallelujah

- Longstreet Farm

- Sex Positive

- False Idols: Boomer Icons And Their Crimes

- Umbrella Blackout: China's War On Digital Activism

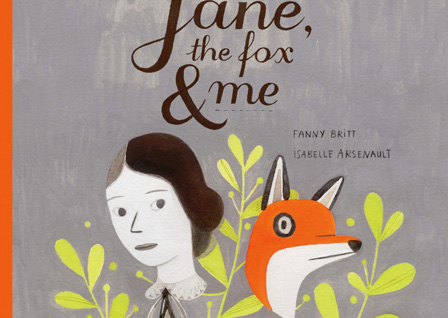

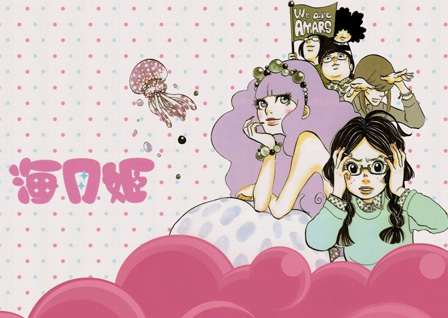

Jane, The Fox, And Me

by Fanny Britt and Isabelle Arsenault

104 pages

ISBN: 1554983606 (Amazon)

Genre notes: coming-of-age, self-image

I'm still not exactly sure of the place and import of the titular Fox, but this was a surprisingly lovely story. It's about a girl who is concerned about her weight and feels the brunt of social antagonism at her school (even though just a year prior she was friends with all the popular girls). She also likes reading and over the course of the story moves through the text of Jane Eyre. It's sweet without succumbing to that overly treacle sentimentalism that costs too many books their laurels. And it's beautifully illustrated.

Dogs Of War

by Sheila Keenan

208 pages

ISBN: 0545128889 (Amazon)

Genre notes: dogs, war

I'm not a dog person. by which I do not mean that I bear any sort of antipathy toward dogs. I merely regard them as I do any animal that doesn't occupy much space in my thoughts throughout the day. Aardvarks, okapi, turtles, salamanders, cats, deer, etc. I mean, they're no meerkats, ammirite?

In any case, despite not being overly concerned with our canine friends, I was taken in by Keenan's three stories about service dogs and their adventures in the midst of the horrors that humankind unleashes on itself and everything that gets in its way. Moving, triumphant stories well-told.

Pink

by Kyoko Okazaki

256 pages

ISBN: 1939130123 (Amazon)

Genre notes: culture critique, prostitution

Much in line with Okazaki's later work Helter Skelter (which we noted earlier on the list), Pink takes a bit more comedic look at social requirements placed on women in late-twentieth-century Japan. But because certain things are too much universal, the book remains relevant to present readers in the US. Dark, cynical, biting, and revelatory.

The Building Opposite

by Vanyda

168 pages

ISBN: 8493399280 (Amazon)

Genre notes: day-in-life

In an apartment building there are lots of stories rumbling and thumbling over each other concurrently. Vanyda looks in on the occupants of three apartments in a single building over the space of a couple months. With an eye for detail, she crafts something immediate and believable.

Hark A Vagrant

by Kate Beaton

168 pages

ISBN: 1770460608 (Amazon)

Genre notes: history, literature, humour

Full review

It takes a steady hand to string together an intricately woven, deeply nuanced plot. The number of authors who can take a handful of seemingly contrived elements and produce an elegantly composed narrative admixture are few and rare. Plot-heavy literature, when it succeeds, is a wonder to behold; but in its failure, we find little to surprise us. So when I describe Kate Beaton’s Hark A Vagrant! as paean to complex plot structures and hail it as deviously devised, I hope you’ll pay attention. The book is a marvel.

Of course some might blanch at seeing Beaton’s book described as plot-driven, but those are simply people who have not yet grasped the book’s primary aim, the goal to which it aspires and ably reaches. If Hark A Vagrant!'s single-minded storyline is to be described in succinct terms, here is probably the simplest explanation: Hark A Vagrant!'s plot is the story of how Kate Beaton made me laugh more than any author.

Hark A Vagrant! presents a collection of historically- and literary-minded humour strips that run the range from dry witticism to baudy toiletries. Being a fan of both history and literature probably helps a reader appreciate the particular kind of crack that Beaton’s cooking up, but there’s a lot of low-hanging fruit as well. Some of my favourite bits were a series of strips in which Beaton takes covers of Nancy Drew mysteries and extrapolates a scene or plotline based on those singular images. As well: there’s a bunch of Canadian stuff I didn’t get. Sorry Canada for knowing next to nothing about your history or culture (though I did recognize Louis Riel!). Beaton also does this wonderful thing where she’ll add commentary to select strips, somehow further ennobling the experience (and sometimes actually educating or at least piquing curiosities).

Y: The Last Man

by Pia Guerra

10 vols

ISBN: 1563899809 (Amazon)

Genre notes: post-apocalypse

Full review

With a subject as ripe for exploitation as a tale of a single man left alone with a world of women, Vaughan and Guerra exert considerable restraint. While the characters are indeed sexual beings (even as we are), they are always first and foremost individuals (even as we are). There are women who can’t live without their men. There are women who rejoice that the patriarchy is finally and truly vanished. There are those who take stock of their lives and move on as they might. There are those who take charge, those who acquiesce, those who are violent, those who are scientists. Really, every kind of individual you could think of exists as denizen of this new kind of life. And their ideologies are equally diverse. As far as speculative fiction goes, Y: The Last Man solidly hits the right notes, being funny, grim, and mind-blowing for its duration. The book has lessons to leave and pedagogy to forge, but never gets too preachy—and the moment it begins wading in that direction, the characters themselves seem to call Vaughan on the carpet for it. These are intelligent people and pretty well representative of the human race. While the book most overtly concerns Yorick and his quest, Y: The Last Man is not a story about men. Rather, the book seems to use the “world unmanned” concept as little more than a framing device for an exploration of humanity itself (and to a lesser degree, women specifically). Vaughan and Guerra succeed in taking a genre concept that could have been the basis for the typical male fulfillment fantasy and spinning it into one of the more worthwhile fables out there.

Castle Waiting

by Linda Medley

2 vols

ISBN: 1560977477 (Amazon)

Genre notes: faery tale, life

Full review

In Castle Waiting, Linda Medley accomplishes something unique by proposing a medieval fantasy setting and then using it mostly to set stage for a series of character-driven episodes of people who mostly just talk about their lives. The castle at Brambly Hedge is the product of a sleeping beauty-style curse. For a hundred years, the fortress was grown up with a forest of thorns dangerous enough to end the lives of any adventurers who set out to discover the mystery of the place. Generations later, a charming prince finds his way through unscathed, wakes the princess, and the two of them leave the castle (and its servants) behind for a bright and ego-tastic future somewhere less provincial. A generation after that, the only ones left in the castle are the princess’ three handmaidens (now old), and they elect to turn the castle into a sanctuary for those in need.

That was all prologue and at the book’s real beginning, a pregnant Lady Jain arrives seeking safety inside the castle’s walls. She is fleeing from her husband lest he discover her pregnancy by another man and kill her for jealousy. Of course, all of this sounds not exactly untypical of the standard fantasy work. Maybe it’s rare to have a female protagonist open an epic adventure by running away with a baby in the belly, but everything else sounds pretty standard. It’s just that when I said this is where the book begins, it’s also pretty much where the story (in any grand sense of the term) ends. The moment Jain enters into the Castle Waiting, all larger plot movement halts entirely and nearly all focus homes in upon the development of the relationships between Jain and those who make their home in the castle. Each member of the community has a unique and compelling personal history and the simmering of their persons and circumstances makes for enjoyable reading. As with any book that puts the interpersonal dynamic on the front shelf, Castle Waiting stands or falls on its characters. Medley puts a lot of heart into each of these, giving them each their opportunity to win the affections of readers. She approaches their interactions with wit and humour. Those in search of dour characters bemoaning the lot their life has drawn will be disappointed, for everyone approaches life with a certain optimism and joie de vivre—save perhaps Henry (who is still working through things) and Doctor Fell (who’s really just kind of gone around the bend due his own grave circumstances). Castle Waiting is, almost more than anything else, a happy book. And one that I am happy to recommend.

How To Be Happy

by Eleanor Davis

152 pages

ISBN: 1606997408 (Amazon)

Genre notes: anthology, sci-fi, life

Full review

Eleanor Davis spends almost the entirety of How to Be Happy offering a delicious exploration of the tie between utopia and dystopia, between paradise and infernal paradise. It’s a fine balancing act, funambulating between hope and despair, but she travels back and forth the distance with sure feet. On only two occasions amongst the collection of shorts does Davis overtly invoke the concepts of utopia and dystopia (once even going so far as to use the word dystopia itself), but for the most part she keeps the theme as mere atmospheric hum. One could be forgiven for not using the idea of earthly paradise as a governing filter for the work if it weren’t for the book’s title, How to Be Happy.

Utopia, the word, is derived from two pieces. The first, eu-, means “good” and sees itself in common English use in euthanasia and euphemism. The second, topos, means place and we see this term crop up in the cartographic practice of mapping topography. Utopia, then, is a good place, a kingdom of peace and security. Of happiness. A society coming to a place of peace via learning how to be happy is an essential piece of utopian presence. Without a general sense of happiness (no matter how broadly we define happiness) amongst the beneficiaries of a society, we have no utopia.

How to Be Happy appears as a dialogue or argument between a handful of ideologies unaware of each other’s presence. They don’t interact directly and orate as if theirs was the only voice in the room. Davis emphasizes this sense by illustrating many of these episodes using entirely different techniques and employing entirely different styles. One story appears as a colourful screenprint with absolutely no linework. The next could have been drawn with a Uni-Ball and features an oversaturation of watercolours. One has very detailed illustrations with strong negative space and sepia tones, another is washed and gentle with mysterious and lovely creatures, another is straight black-and-white with drawings that call to mind the childhood adventures of Nate Powell’s Any Empire. And there’s more. Davis is clearly talented and diverse. If one wasn’t aware, it would be easy to mistake Davis for the collection’s editor and the individual stories as the anthologic production of a number of artists.

Friends With Boys

by Faith Erin Hicks

224 pages

ISBN: 1596435569 (Amazon)

Genre notes:

Full review

Faith Erin Hicks parlays flavour from her own homeschooling experience into a young-adult vignette of a young woman’s first days in a public high school. Maggie is anxious, unhappy, and maybe even a little bit terrified as she has to adjust to an educational dynamic that is not governed by her now-absent mother. My wife (homeschooled) confesses to having nightmares as a youngster that she would—for reasons contrived only in the logic of dreamworlds—be forced to go to a public school. There was even a time in junior high when she was invited to a friend’s school for the day and she almost died of anxiety trying to concoct a scheme how to get out of the invitation. So Maggie’s misery over her new situation is apparently pretty believable.

And while Hicks obviously has her own thoughts about homeschooling, she doesn’t bang any drums in defense of or aggression toward the educational alternative. Hicks even has the opportunity when a new friend of Maggie’s (previously, her only real friends were her older brothers) remarks at how she’s not actually completely socially dilapidated. It’s a great opportunity for Hicks to spaz out and diatribe in whichever direction she leans, but instead the author plays the moment out quietly, amusingly, and with little fanfare. Maggie’s story reads, for its duration, as believable, human, and not really at all interested in making any kind of dogmatic personal statement—a valuable lesson in storytelling for those who’d rather make their points overt (and therefore trivial).

Friends With Boys is more than just a homeschooled-fish-out-of-water story. There’s the part about adjusting to life without mom, the part about redemption from past mistakes, the part about forgiving and forgetting, the part about how jerks will be jerks. And there’s the part about the ghost. While Friends With Boys is about more than just a homeschooler trying to adjust to the “real world,” it’s the book’s exploration of a particular homeschooler’s life and distress that makes it such a winning story. Maggie is an endearing protagonist and her homeschooling-derived hesitations and insecurities are entirely understandable. When she makes friends, we as readers buy it. When she makes mistakes, we also buy it. She’s a whole person and even if she has quirks that we ourselves may not exhibit, they’re of an order familiar enough that any one of us very well might. We might even be surprised at how normal Maggie is for a homeschooler.

Saturn Apartments

by Hisae Iwaoka

7 vols

ISBN: 1421533642 (Amazon)

Genre notes: speculative fiction, life

Full review

The futurism and social state of Saturn Apartments seems in place wholly to the end of presenting a fully forged world in which Iwaoka’s small story can take place. And when I say small story that is only to say that this is not a book devoted to national or interspecies struggles. This is not a series about the end of the world (in a way, that already happened). This is not the story of good vs. evil, the rescue of a princess, or a race to recover a lost treasure before it’s lost for all time. It’s the story of a boy who’s just joined the workforce and is trying to come to grips with who he is in the shadow of his father’s death five years earlier.

And in that way, Saturn Apartments may actually be a bigger story than Star Wars or Lord of the Rings. After all, every person is an expansive universe of interests, motives, stories, treacheries, and dreams. And each of these universes is governed by an entirely unique set of forces, every bit as sovereign as gravity and entropy.

Fullmetal Alchemist

by Hiromu Arakawa

27 vols

ISBN: 1421541955 (Amazon)

Genre notes: adventure, magic, epic

Action adventures are not quite my bag but this series is pretty incredible. It's thorough, well-planned, and the characters are worthwhile. The high-action conclusion was less interesting to me simply because I don't care much for action, but if you like heroes or shounen or epics that tie up ends, this is like gold for you.

Super Mutant Magic Academy

by Jillian Tamaki

224 pages

ISBN: 1770461981 (Amazon)

Genre notes:

I caught Tamaki's series occasionally in its online publication—but so occasionally that I was unaware that it wasn't just a series of quirky one-off gag strips. Reading the entire thing on paper and in a single sitting was a joy.

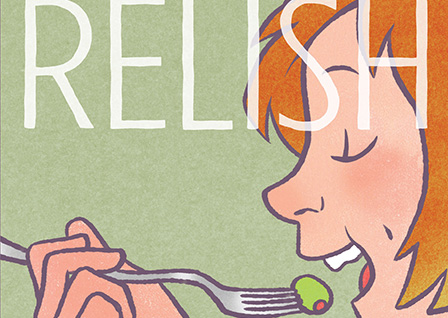

Relish: My Life In The Kitchen

by Lucy Knisley

173 pages

ISBN: 1596436239 (Amazon)

Genre notes: memoir, food

Full review

Knisley’s memoir is composed of twelve short chapters that roughly trace the chronology of her life, and each pericope develops around the various foods she associates with those stories. She intersperses narrative delights with recipes for favourite foods and a helpful fact sheet explaining the complicated world of cheeses. None of my description of this, however, conveys the pleasure and excitement Knisley’s pages draw forth.

Her work is bright, colourful, humourous, and (best of all) exuberant. The joy Knisley evidently takes in the act of tasting is translated almost perfectly through both her narrative choices and the manner of her execution. Her characters are lively and their expressions telling. She narrates her story with a confident voice and as much as she talks about food, good food, and even gourmet food, Knisley never approaches that smug condescension that has become the signature delight of the foodie crowd.

Written In The Bones

by Carey Pietsch

8 pages

Read Here

Genre notes: dogs

As noted earlier, while not antipathetic to dogs, I am not what anyone would consider a dog person. One of the big surprises for me then was this mini by Christopher M. Jones and Carrie Pietsch, about a dog father mourning the loss of one of his sons and wondering at the apparent ambivalence of their owners. It's a solid story—great, really—and it shows off both creators' talents well. Visually and tonally, it's different from anything else I've seen from Pietsch. Also, it broke my heart.

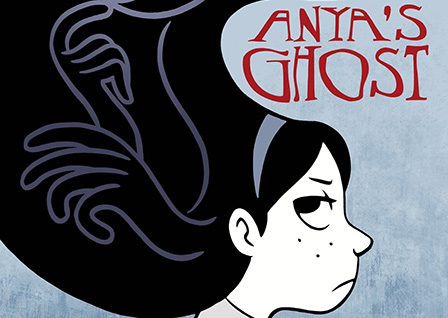

Anya's Ghost

by Vera Brosgol

224 pages

ISBN: 1596437138 (Amazon)

Genre notes: high school, immigration, ghosts

Full review

Brosgol works hard to make Anya a character who very easily could be weird or strange or unwelcome but isn’t. She’s a typical teen from an immigrant family. She herself is an immigrant and by her word we learn that she’s worked very hard to compensate for her inauspicious country of origin. She’s overcome her accent, acclimated to the cultural diversity of young American life, and doesn’t dress like someone who’s just discovered clothes. (Apparently dressing like someone who can put together a plausible outfit is not something immigrants can naturally accomplish?) She’s also embarrassed by her native culture and goes to lengths to distance herself from that which will mark her as Foreign. Sometimes that means shortening an obnoxiously difficult-to-pronounce last name and sometimes it means forsaking the other kid from your country who hasn’t quite overcome his eager-foreigner tendencies yet.

In a lot of ways, Anya’s Ghost explores the same cultural experience Gene Yang looks at in American Born Chinese, the barrier between being true to our own identity and being accepted by the world around us. While Yang’s protagonist gets a perm and imagines himself white, Brosgol’s Anya is determined to be assimilated. Both books speak gently to the threat of alienation, to the social stigma attached to not fitting in. Both works, in the end, admonish the reader that fitting in isn’t the be-all, end-all of human—let alone high school—existence. And best of all, neither book comes off overly preachy in their lessons, which is always nice for stories that contain overt morals at book’s end.

In The Sounds And Seas

by Marnie Galloway

168 pages

ISBN: 193554876X (Amazon)

Genre notes: myth, women, nautica, art, dreams

Galloway’s short book, In the Sounds of the Sea, is one of the most beautiful books I've seen. It's opener, a creation myth of sorts, is incredible and worth the price of admission. Galloway has three women sitting around a campfire, singing. As each raises her voice, creatures emanate in a torrential stream, rising to the sky. One woman sings forth birds, another fish, and the other rabbits. The three streams twine and braid, becoming one and blending together eventually into an Escher-esque sea of life. It’s entirely gorgeous and worthy to fill a living room wall—or perhaps swaddle an adventurous tattooed torso.

Ghosts

by Raina Telgemeier

256 pages

ISBN: 0545540623 (Amazon)

Genre notes: ghosts, fantasy, illness, life

In Ghosts Telgemeier creates a warming story of life and death and undeath and the celebration of each. It's a bit of urban fantasy that serves as a moral reminder of the value to our mortal period and the importance of not squandering that. Well-paced and readable.

Soppy: A Love Story

by Philippa Rice

108 pages

ISBN: 1449461069 (Amazon)

Genre notes: memoir, romance

This book is adorable, capturing those lived in moments that so many love lives harbour. It's delightful and exuberant. It captures none of the struggles that too oten hamper true communion between souls, but rather than open itself up for critique of being too romantic or too positive, it simply reminds us that between two lovers, joy can easily be found. In simple things, in daily routines, in each other.

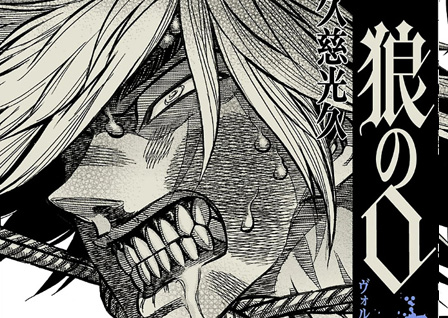

Wolfsmund

by Mitsuhisa Kuji

7+ vols

ISBN: 1935654756 (Amazon)

Genre notes: history, action, war

Full review

Wolfsmund has the same thing going on. The first two volumes are relentless. They’re gruesome and draining and don’t really seem to go anywhere. It’s just ugly death after ugly death, and Kuji seems to introduce characters only to see them tortured and dead by chapter’s end. It’s maddening and sometimes off-putting. But then, like the book of Genesis, suddenly things start happening. The loose threads of a plot begin to weave into sight and all of that earlier horror begins to make a bit more sense.

Wolfsmund is a kind of fan-fictional retelling of the fall a particular garrison in an isolated Swiss pass. It’s a little bit confusing as it takes place on 15 October 1315 and seems to be concerned with the Battle of Margarten, which took place a month later on 15 November. Maybe the current arc is merely prelude for the later battle with Leopold. Whichever the case, Kuji offers an exciting version of the events and gives her characters near superhuman martial prowess. William and Walter Tell are not only expert marksmen, but they can catch themselves on shear rock walls by a couple fingertips on centimeter large outcroppings. A farmgirl’s husband was murdered she and her two servants become experts in a farming-implement-focused combat style that her late husband had developed. Et cetera. There are speedlines and choreographed action out the wazoo—and it’s actually kind of magnificent in its way.

Those looking for a staid encounter with the dry history of a bloody, lopsided battle are going to be probably disappointed—such was never Kuji’s aim. Rather, she has put together a brutal, sentimental action-film spectacular. In all honesty, I probably would have preferred the more true-to-canon version of things, but not only do I respect Kuji’s choice, I also have come to pretty thoroughly enjoy it. It’s not by any stretch a perfect work, but especially for one’s first headlining project, she shows an able commitment to her vision.

City In The Desert

by Moro Rogers

428 pages

ISBN: 0692571469 (Amazon)

Genre notes: adventure, myth

Due to a bizarre sort of mismanagement by Archaia and then Boom that kind of pissed me off at the time, Rogers' book (broken into an awkward trilogy presumably for publisher dollars) never saw publication of its third part. So I had two gorgeously produced books that would never be complete.

Fortunately, Rogers has since self-published the entirety in a single volume (as intended). And it's a very good story. Mythic and sweeping and exciting and sad.

Baggywrinkles

by Lucy Bellwood

132 pages

ISBN: 0988220296 (Amazon)

Genre notes: maritime experience, tallships, memoir

I'm not any particular fan of autobio in comics (or in prose for that matter), but Bellwood's adamant joy in her subject (not herself but in ships and the sea) is deeply infectious. In my review for Broxo I speak a little about how I can no longer adventure:

I used to be pretty athletic. Hiking, skimboarding, boogieboarding, skateboarding, running, jumping, destroying things that weren’t my body. It was an awesome time to be alive. I was reckless and wild and harboured little care for decisions that entailed in some form or other the principal question of How much is this going to hurt? Twenty years later, nearly every activity I choose to engage revolves distinctly around how much discomfort or outright pain the activity might incur. Because unfortunately, all those wonderful things I could do eventually seemed focused on a single goal: destroying things that were my body.

In my early-to-mid twenties, miscalculation and overestimation brought me injury after injury. Head injuries, neck injuries, back injuries. Ankles, shoulders, fingers, hands, knees, groin. Injuries so far as eyes could see and injuries in dark places hidden by layers of flesh and sinew. I was used to healing quickly and so used to returning to activity quickly, sometimes even instantly. As I grew older, the pace of my healing slowed but my habits didn’t care and so I bounced back from my wounds too quickly and, being off-balance, slow, and in a body that wasn’t one-hundred-percent operational, I compounded my injuries. The fallout of course is that now, so many years later, I live in near constant pain. From ankles that sprain and swell while Facebooking to a back that cannot survive a sneeze to shoulders that cannot throw a tennis ball overhand. Sitting on the ground for a half hour will ruin me for a week. Rolling over in bed means waking again for the tenth time in half as many hours. Fascinating, I know.

That was long to get through, I know, but the point is: I am no longer physically able to do many of the things I'd love to do. Camping, hiking, backbacking across Asia, going to sea, walking the mile around the lake next to my house, etc. So I live vicariously through the joy of others' experiences doing these things. Bellwood took me on so enjoyable and educational a trip that I'd love to read more from her on the subject.

The Story Of My Tits

by Jennifer Hayden

352 pages

ISBN: 1603090541 (Amazon)

Genre notes: memoir, breast cancer

This is Jennifer Hayden's memoir through the lens of her breasts, from anticipation to impatience wondering where they were to disappointment to a full bosom to her mother losing one to cancer to childbirth and breastfeeding to her own cancer and double masectomy to reconstruction.

It's a funny and sad and triumphal book. I cried a little at several parts and laughed loudly at others. The book is strongest in its introductory portion showing Hayden imagining life with breasts and impatiently awaiting their arrival—and then again once Hayden gets cancer. As with most memoirs, we have to endure the college aged version of the storyteller who will always be insufferable (because we all are at that age). The middle section feels a little bit wobbly and unfocused, but once cancer takes the stage in the final third, the book regains its footing and finishes strong.

What Is Obscenity?

by Rokudenashiko

168 pages

ISBN: 192766831X (Amazon)

Genre notes: memoir, obscenity laws, vulvas, patriarchy

By relating her own trial and imprisonment for creating manko art, Rokudenashiko incisively critiques the world of male-dominated governance that hypocritically polices what can and cannot be seen and discussed in Japan. And while her experience is thoroughly Japanese, there should be enough hooks for Western readers to look questioningly at their own cultural mores. Solid work and highly recommended.

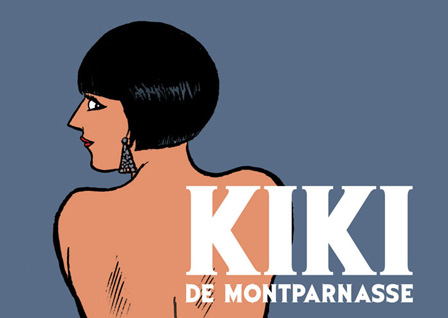

Kiki De Monteparnasse

by Catel Muller

416 pages

ISBN: 1906838259 (Amazon)

Genre notes: biography

Full review

In Catel and Bocquet’s biography of Alice Prin, better known as Kiki, the reader is rushed through fifty-two tumultuous, extravagant years of a woman’s life. Kiki is one of those figures whose existence is simultaneously extraordinary and clichéd. Extraordinary because she lives in that larger-than-life manner that can’t possibly seem to sustain itself. Clichéd because it doesn’t. Like so many of those who burn brightly enough to catch the eye of the everyman, Kiki flares out, smouldering and spent.

The publisher’s description that graces the book’s cover is bizarre. After describing Kiki in terse encyclopedic summary (model in Montparnasse in the '20s, partner to Man Ray, painted by Kisling, Foujita, et al), it embellishes grandly: “she is the first emancipated woman of the 20th century” and ironically goes on to cite her sexual, emotional, and whole-persona liberties. The irony, of course, is that Catel and Brocquet demonstrate so much the opposite of this over the course of their treatment of her life that one wonders if the publishers were being merely playful or if they truly misunderstood the work before them.