Last year, I decided to shake things up a bit by turning my Best Comics Of The Year list into a Best Comics I Read Last Year list. If anyone minded, they didn't tell me about it. Why did I make this change?

The cult of the new has got us down, and I think about it more and more every passing while. We miss so much by focusing wholly on what came out in this last year. These lists published by big outlets every November (!) or December (if we're lucky!) read more and more to me like evidence of missed opportunities rather than any kind of collation of the best of the medium released in any given circuit around the sun. The number of truly wonderful books that don't get any recognition in the year they're released is probably bigger than you think, definitely bigger than I want. I would traditionally hold my own annual list 'til February in some vain attempt to access more of the available books that should place on a list like mine. I would inevitably miss stuff. Sometimes ridiculously good stuff. And my loss is my readers' loss.

As a case in point, nobody put Joshua Cotter's Nod Away, vol 2 in their best-of list in 2021, and it was easily one of the best comics of the past few years—I had it as №2 in my 2020-2022 list. People are talking about it more now, but it took more than that first year to gather any steam. My №2 book this year has, so far as I'm aware, not been featured on any best-of list (we'll wait on the annual Jamie Coville round-up to be sure) despite this being the year that its series wraps.

This is, I think, a problem. Not a big problem, but unlike the *actually* big problems, it is a) one that affects me in some near-tangible way and b) one that I can take some small action toward a remedy.

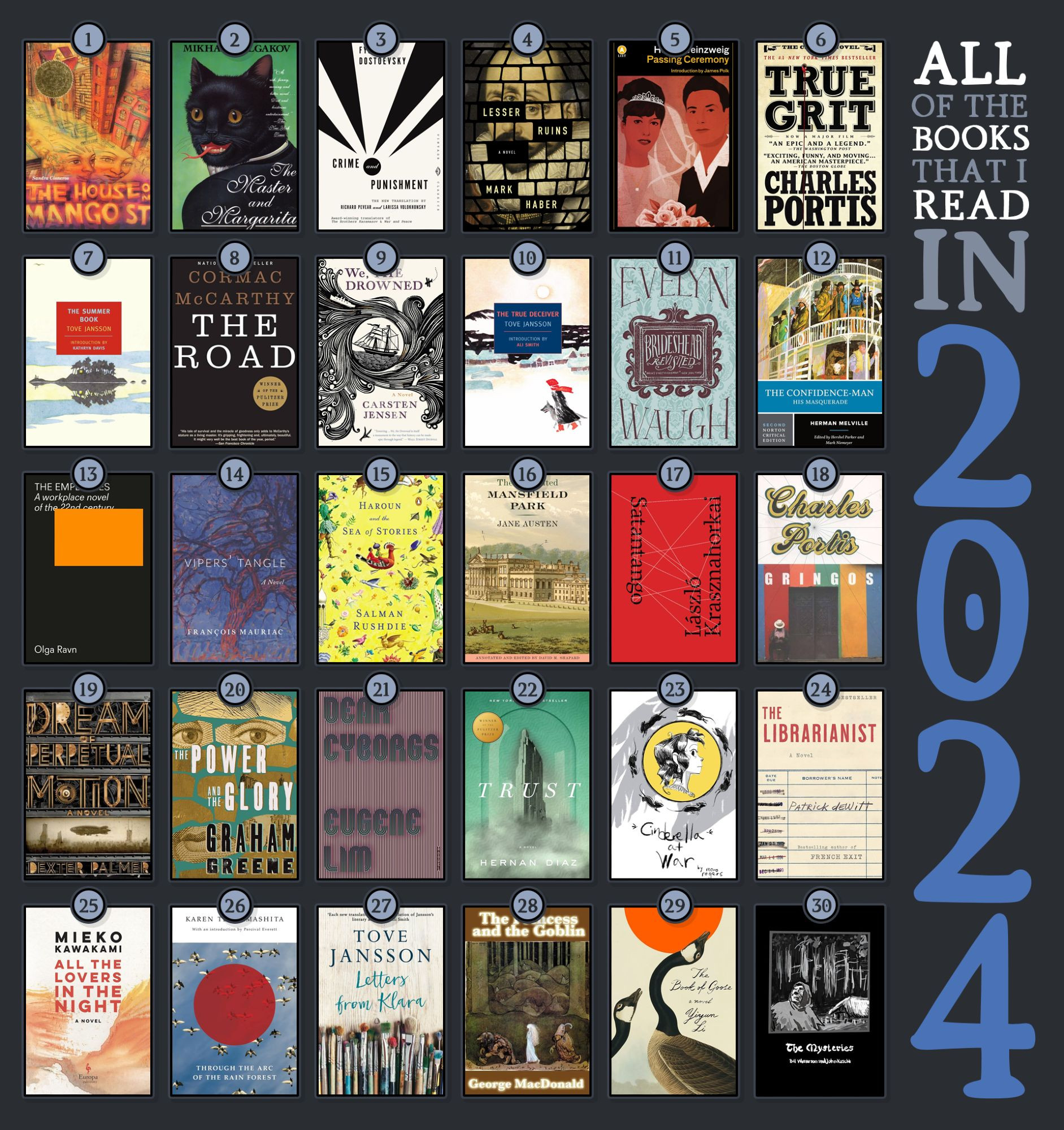

So for this year's list (as with last year's and presumably those going forward), I'll be doing the Top 50 books I read for the first time in 2024 (or well, in the year since I last made a Good Ok Bad list). This way, I get to celebrate older comics I've encountered for the first time alongside great books published in the last year. For those who still really want to know what on this list is new, I'll include a little 2024 badges on appropriate works and list them in order of preference at the end to kind of give you a mini Best-Of list.

Coming up with a ranked list of things for a personal site or post on Facebook is entirely different in nature from ordering things for a Serious Critical Outlet (which I vaguely pretend to be). I can't just post What I Liked because 1) I have a site mission to consider and 2) for the list to be recognized as worthwhile to most readers, it has to contain enough of those things that other people would list to seem legit.

And while I never cheer on popular books that I hate just for the concept of earning legitimacy, there's always a bit of artificial list reorganization that is maybe even subconsciously designed to appeal to a readership. And maybe I'll even bump up a smallpress indie book that you can't even buy because Man that makes it feel like I'm serious about comics and you should trust me. (By the way, I *am* serious about comics and you definitely *should* trust me.) But maybe I won't do that. Most of these motivations are present but subconscious.

Does the fact that I'm on friendly terms with some creators give those books a bump? I don't see how it couldn't, even if I'm not conscious of it happening. When you read a good book by a stranger, you think, "Hey that was good!" When you read a good book by a friend, your naturally warm feeling for that other person blends with your experience of the book (because nothing social occurs in a vaccuum) and now you think, "Man, that was a good book! I loved it!" And of course friendship also tends to soften criticism as well. Because we're not robots, you and I.

Also, I have to balance in some sort of subjective rubric for valuating a) What I liked with b) What is valuable and c) What is high in craft-quality. Every year, I find creating the list more daunting and more frustrating. Especially since not only is #26 not substantially "better" than #27 but also #26 is likely not substantially better than #45. I mean, it's a good problem to have. Lots of good books to read. And more every year. Essentially, we will never run out of good comics to read. It's like a golden age or something.

SupportProse I ReadNavel Gazing

My Best 50 Comics of 2024

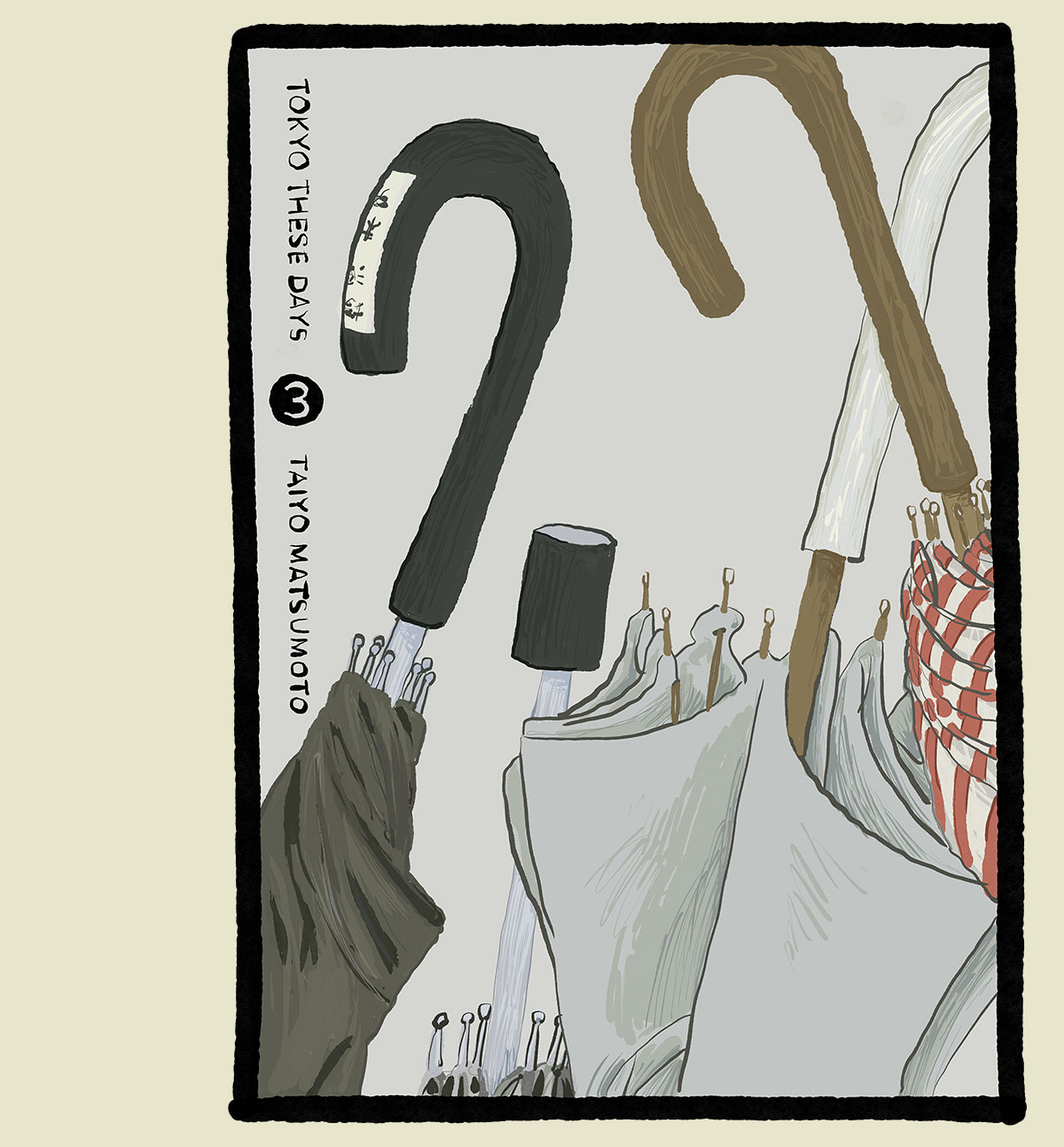

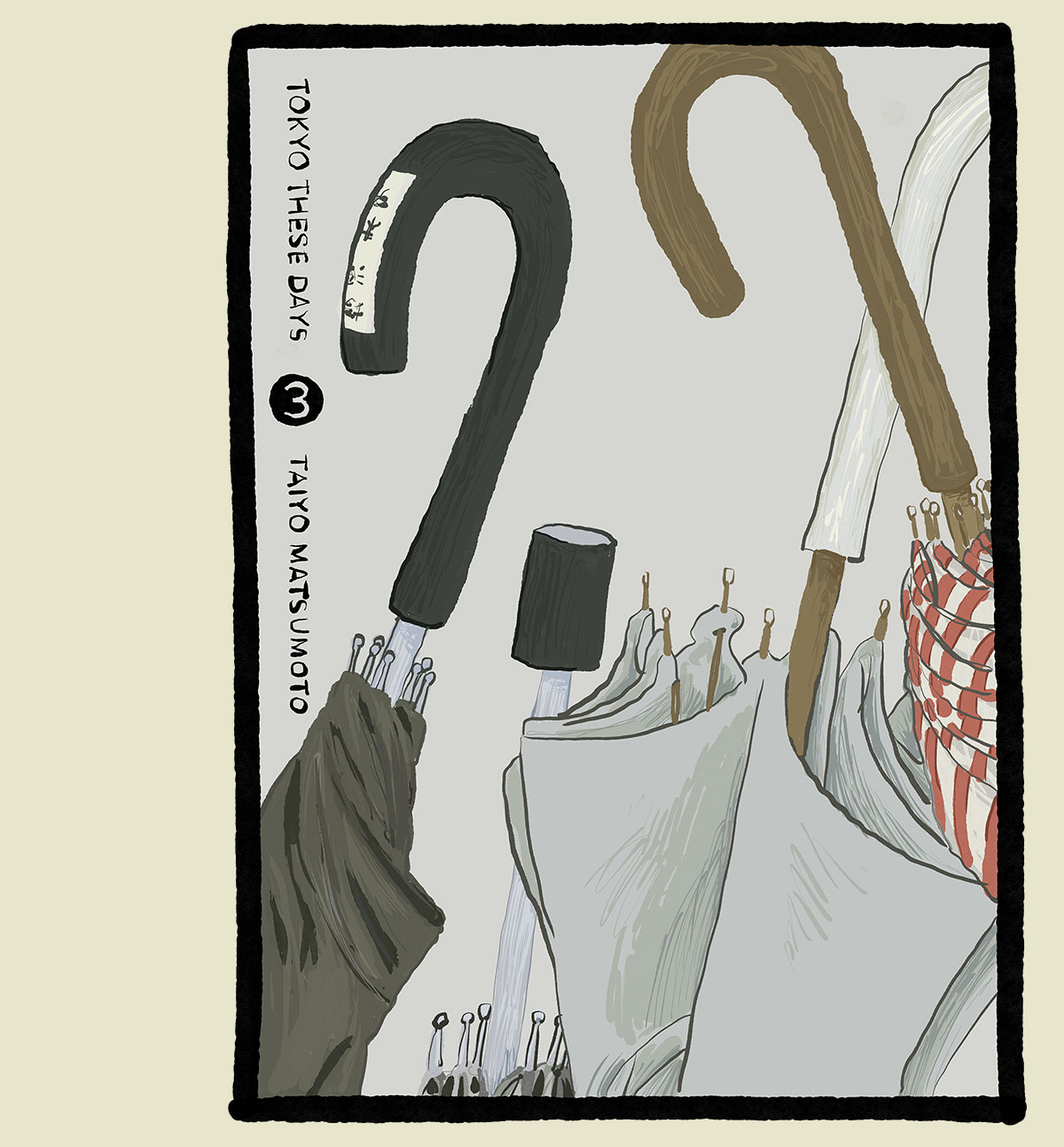

Tokyo These Days

by Taiyo Matsumoto and Saho Tono (translated by Michael Arias, lettered by Deron Bennett)

3 vols

Published by Viz

ISBN: 1974738809 (Amazon)

Among the foremost comics creators in the world today, Taiyo Matsumoto pairs with his wife Saho Tono to tell the story of Shiozawa, a longtime comics editor who's recently retired as penance for the commercial failure of his latest magazine but is inspired to throw his entire severance into one final creative endeavor: getting the band back together in a commercially immune bid to make what he considers true comics art. Throughout the story, told over three meandering volumes, Shiozawa recruits (sometimes successfully) from among his favorite creators from across his 30-year career. Most of these are forgotten heroes of an age of comics that contemporary readers have moved past. Some are still creating, but are doing more marketable, less visionary work, and Shiozawa offers them the opportunity to blossom again. Others are retired, now plying menial work as grocery store clerks or building custodians. Some are inspired by Shiozawa's offer while others retreat in fear and self-doubt. All of this is told alongside the rise to stardom of one of Shiozawa's recent young protégés, a man full of bluster and the veneer of confidence. Matsumoto and Tono have laid out a panoply of human experiences.

Matsumoto's body of work rappels from high octane bluster in Ping Pong and Tekkonkinkreet to surreal masterpieces in GoGo Monster and No 5 to the well-observed explorations of the human experience in Sunny and now in Tokyo These Days. Here in Tokyo These Days, Matsumoto and Tono rejoice in the human impulse to create while also exploring the many many many human obstacles to the realization of that impulse: expectations, fears, commercial concerns, self-sabotage, even the simple brute fact of mortality.

Matsumoto and Tono have here created another deeply human work, very observant, and another ode to the experience of living. They've again created an optimistic work that navigates a world of hardship, this time luxuriating in the tension between creating true art and being successful and relevant. It is, of course, a book about making comics. But not just comics—true comics! unmarketable comics!—all with the slim tendril of hope that this perfect art artifact will find the readers who will feel rewarded for having found it. It's a book about selling out, about following trends, about the role of editors for both good and ill. It's about giving up and persevering, about second chances and about giving second chances the finger. It's a book about what comes next. For a series complete in three volumes, it's robust.

Ian M has a great intro to the series (how to read it, why it's great, etc) here:

I'm glad Viz gave this book a similar publication treatment to Sunny—gorgeous, subdued clothbound hardcovers. It deserves it, I think. And we get what appears to be the now official pair of Matsumoto localizers: translation by Michael Arias (who's always been Matsumoto's translator, and even directed Tekkonkinkreet) with lettering from Deron Bennett (Deron's lettered Sunny, Ping Pong, and Cats In The Louvre—though Steve Dutro took on the No 5 edition).

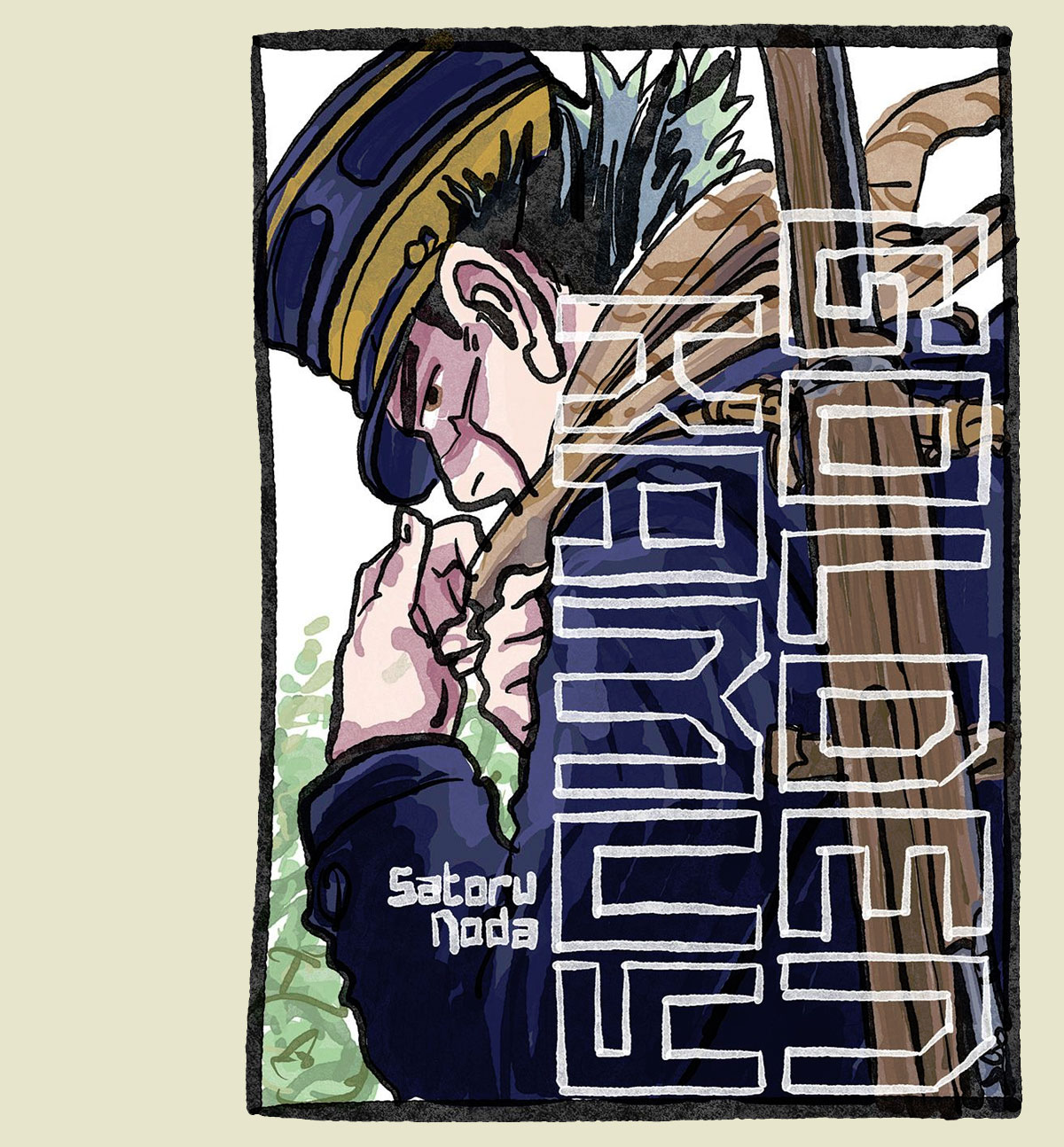

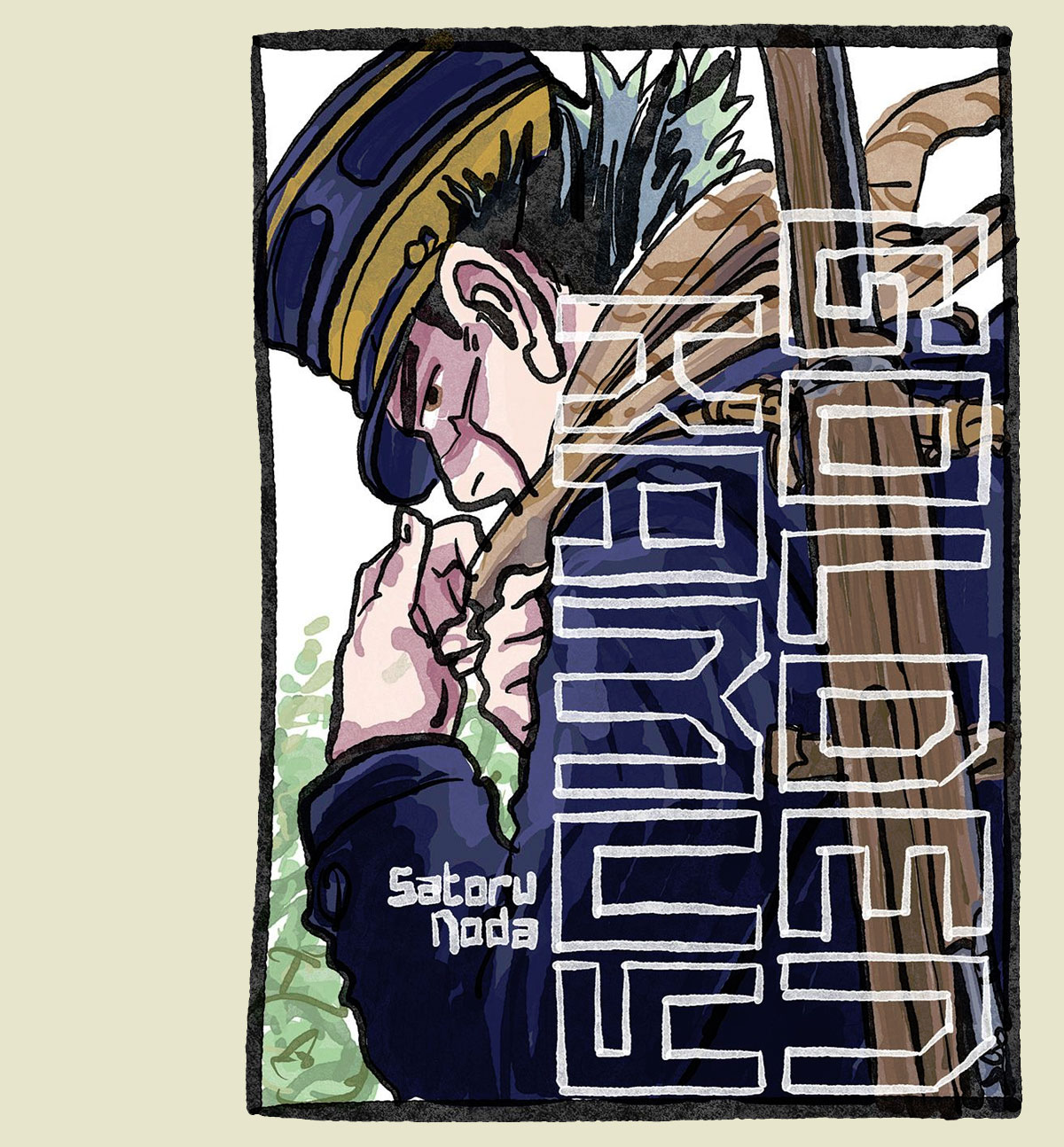

Golden Kamuy

by Satoru Noda (translated by John Werry, lettered by Steven Dutro)

31 vols

Published by Viz

ISBN: 1974741796 (Amazon)

In January 2024, we got the English-language conclusion to Satoru Noda's 31 volumes of post-war gold-hunters, the plight of the indigenous, lessons in naturecraft, and hilariously depraved but often lovable lunatics—and boy howdy is this comics.

Golden Kamuy is one of the strangest, most wonderful adventure stories I've seen. It's terrifically violent, terrifically educational, and terrifically funny. I'd underestimated just how funny, lulled into thinking it would just be an educational adventure romp by the first several volumes that keep the humor subdued and almost rare. Noda's definitely got comedic use of expression down to a science untouched by other human hands, but his comic timing is impeccable as well. Possibly the funniest non-comedy book out there, maybe even funnier than Cross Game (blasphemy, I know), but possibly also funnier than most of the best actual comedy books as well.

Here's a brief synopsis that won't remotely capture the magic of the book but will give you a place to hang your hat, I guess. Sugimoto, a veteran of the recent (1904-05) Russo-Japanese War, has come to Hokkaido during a gold rush hoping to make some money to cover an eye surgery for his former lover and now-widow of his KIA best friend. While trying and failing at panning, Sugimoto accidents into an intrigue involving twenty or so tattoo'd convicts whose tattoos comprise a map to a pile of gold once intended for raising an army. Sugimoto teams with a young indigenous Ainu girl to race against a few other much better organized factions to reassamble the map and find the gold (and maybe start a rebellion). Also: the map tattoos are meant to be assembled by skinning the convicts to put it all together, so... that's a whole thing.

3rd Voice

by Evan Dahm

2+ vols

Self-published

Read at (rice-boy.com)

Evan Dahm's new big project after the close of Vattu is expansive and displays more invention and curiosity about the nature of peoples and cultures than anything we seen from him so far, which says a lot about the fabric of this new world and its characters and narrative.

3rd Voice is about the world that limps along for a bit after the end of the world on its way to becoming something else. A new world, perhaps. With any luck.

While entirely alien to our own world and our sense of it, Dahm's new creation does share some thematic kin to what we find in, say, Canticles Of Liebowitz. It is, of course, actually quite different, but there are vibes and rhythms that I think fit well enough with Miller's own vision of a world crawling onward from calamity. Gods. Demigods. Priests. People. Many have fallen and a few get up.

Aside from a pile of meta-textual videos and background materials (and letter column!) available for interested readers, Dahm employs an intriguing conceit to build our alien sense of things. He uses (in something like the Mighty Marvel Style) editorial notes throughout, sometimes focused on translation of terms...

...and other times noting his position of authorship/interlocution:

These instances from "—ed" propel us into a expression that Dahm is translating or at least annotating. In ways, it feels very much like something Eco liked to play with, proposing that various novels were "found" and then communicated somehow to the reader. It gives everything another layer, making carrying through the narration a more delicious prospect.

Land Of The Lustrous

by Haruko Ichikawa (translated by Alethea Nibley and Athena Nibley, lettered by Evan Hayden)

12+ vols

Published by Kodansha

ISBN: 1632364972 (Amazon)

This is simply an incredible exercise in imagination and storytelling. I never knew where it was going to turn next. With one volume remaining to be released in the US, we're nearing the conclusion to one of the most epic stories in comics.

SYNOSPSIS: The world is very different than it was. There are, essentially, three forms of life: the mollusks, the Lunarians, and the gemstones (our main characters). And Sensei, whatever he is. The Lunarians attack the gemstones fairly regularly for reasons unknown. The gemstones are smartly dressed creatures (coded as vaguely androgynous women) whose toughness and character is related to the Mohs scale of the gem from which they're formed. Most of them are hundreds of years old. This story concerns Phosphophyllite, a fragile and pretty useless gem, as it investigates the world and seeks to understand the Lunarians and the Sensei.

Land Of The Lustrous is kind of amazing in how rapidly a story about incalcitrant, functionally immortal beings evolves and changes. Some of these characters are 700 years old and harder than steel, but the youngest of their group breaks and remolds and grows and shifts in both form and personality and motivation. She doesn't just have a character arc; it's more like a character squiggle.

And the story continues to evolve dramatically. It's impossible to predict what's going to happen next—even up through the end.

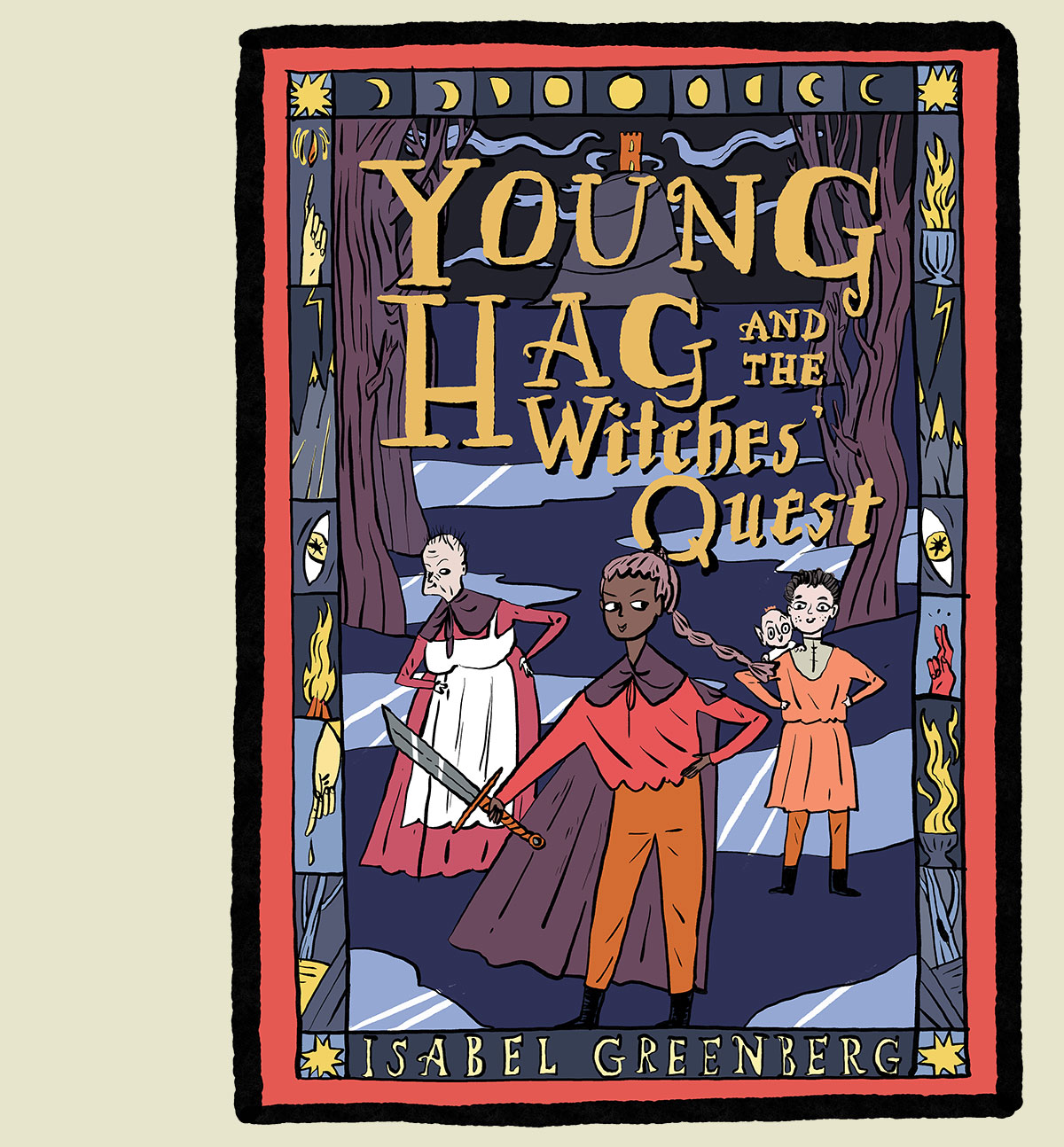

Young Hag & The Witches' Quest

by Isabel Greenberg

288 pages

Published by Harry N. Abrams

ISBN: 1419765116 (Amazon)

Isabel Greenberg's effort to play in the Arthurian vein is tremendous. Greenberg's spent her graphic-novel-making energy on a various paeans to story and the gift of storytelling. From her two Early Earth books to spinning out a telling of the four Brontë's combined childhood mythos to now exploring Morgan Le Fey's story by proposing a new canon involving the witch's granddaughter. (It's good enough that I'm calling is canon at any rate.)

At the beginning of our telling, Young Hag receives her new name, Young Hag, both name and rank, both identity and occupation. It's a solemn moment and happens to coincide with everything going wrong for her, which we all know can also be the impetus for everything going right. Stories, eh?

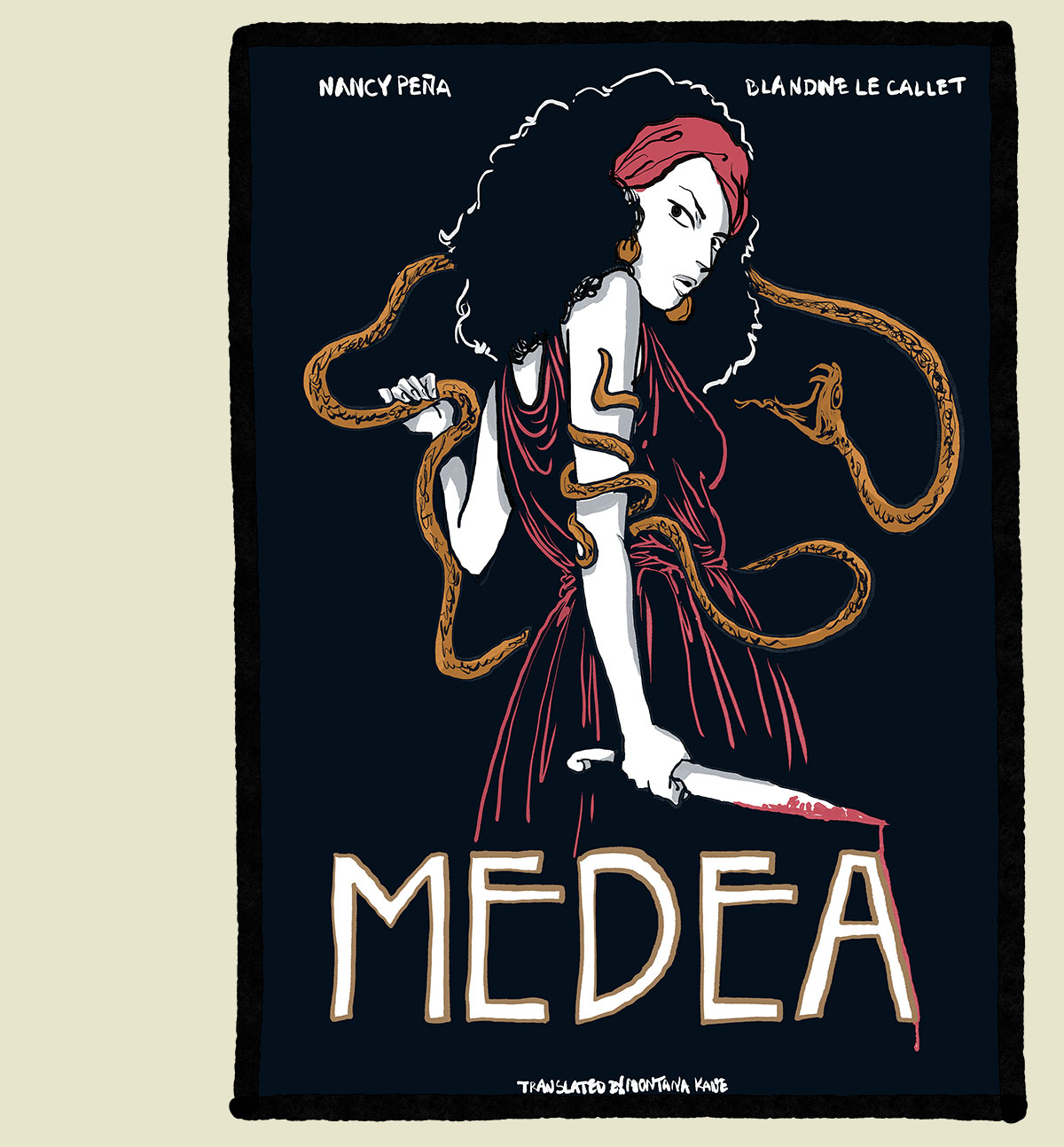

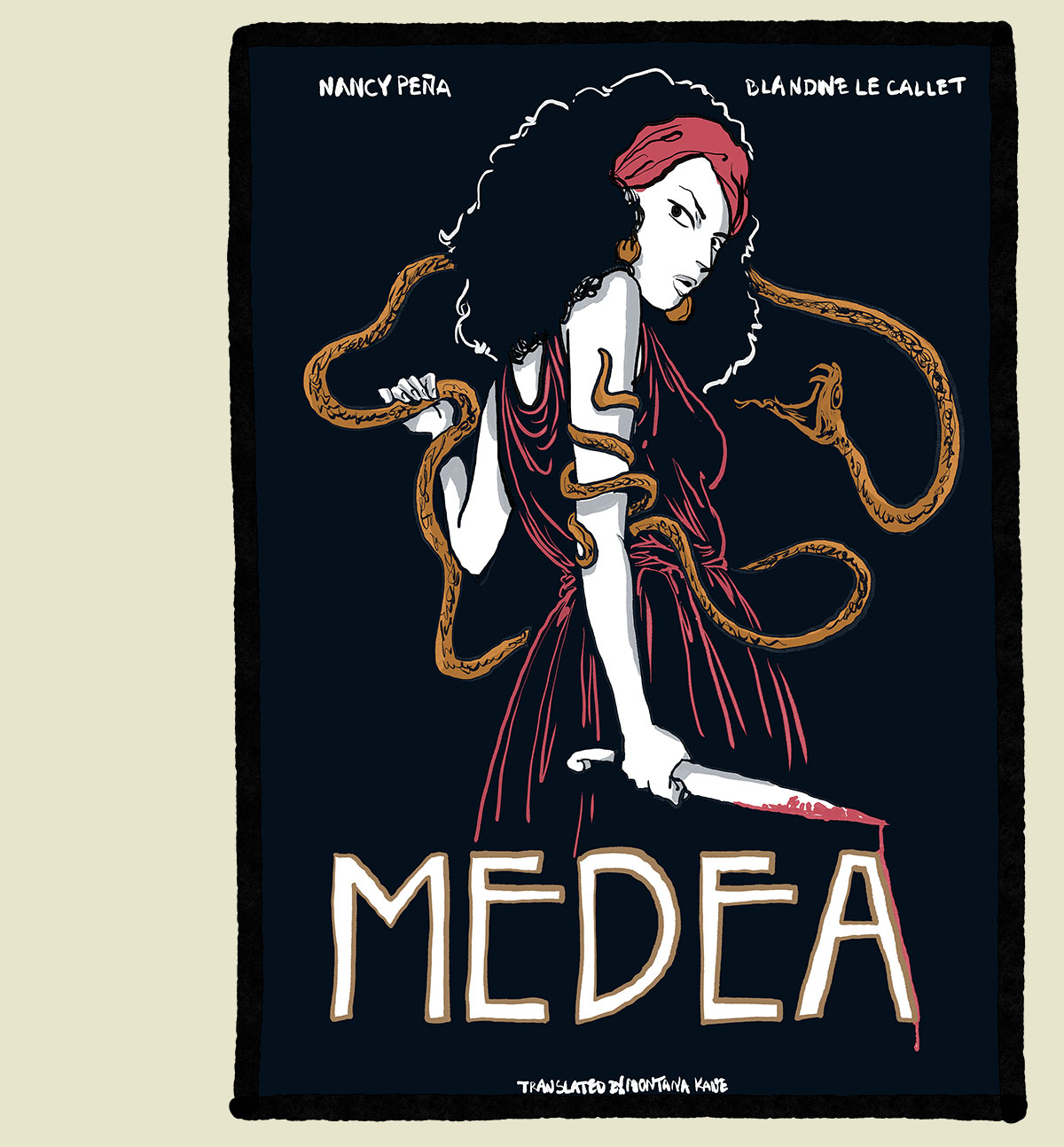

Young Hag somewhat sits in that recent genre of stories that rehabilitate the reputations of the scoundrel women of legend. Other examples include Madeline Miller's Circe, recent social media reappraisals of Medusa, and, later in this very list, Callet and Peña's Medea. I say somewhat because Young Hag doesn't come near approaching hagiography. This is a human story about frail people and how their frail decision shift history in incredible, often damaging ways.

It's bizarre to me that Greenberg's work is not more widely lauded. Critics, I think to a soul, love her. Rightly. But outside of the critical apparatus, I've found Greenberg a particular blind spot among comics readers. I don't understand it. Her work is soaring, astute, romantic, thrilling, and absolutely funny.

[Side rant: It's tragic and astonishing and stupid to me that it's weirdly shelved in Children's Graphic Novels (at my library) or in Young Adults because that pushes it off the radar of most grown-up readers, i.e., those almost certainly best able to appreciate it. That is to say, as with a lot of non-YA books, both adults and teens can happily enjoy it and its themes and how it plays with Arthurian legends and interacts with feminism and patriarchy, but to label it YA or For Children cuts off a lot of its potential audience. This is a book I want adults to read. Obviously yes, there are some great YA books out there. Octavian Nothing is rich and thoughtful (and also reads as if meant for general audiences), so I'm emphatically not saying adults shouldn't read YA. More just that rich and thoughtful isn't probably what general audiences expect from YA, so it's a shame to hide something best aimed at grown-ups behind a childish veneer. This should be shelved with the general graphic novels and let the precocious kids do what comes by them naturally.]

Lunar New Year Love Story

by Gene Luen Yang and LeUyen Pham

352 pages

Published by First Second

ISBN: 1250908264 (Amazon)

Lunar New Year Love Story is much more than is proposed on the tin. While, yes, it is something of a rom-com, it's thoughtful and inventive in a way we don't typically get to see from the stuff that makes our hearts trill.

This story captures so well warmth in hardship, how the one (warmth) buoys against the other but can also be made full by the other. My heart was thoroughly lodged in my throat for the final third (I was in a continual state of feeling moved), but even the first two thirds were an exciting mix of revelations and touching moments. An absolutely delightful story that I'll be recommending to friends for years to come.

I only knew Pham's work from the delightful Templar, drawn with Alexandre Puvilland, and an awareness of the Real Friends trilogy (which I've not read though my kids will vouch for them). The dance she weaves through Yang's writing is lovely and she breathes a perfect kind of life into these kids and their thrills and agonies.

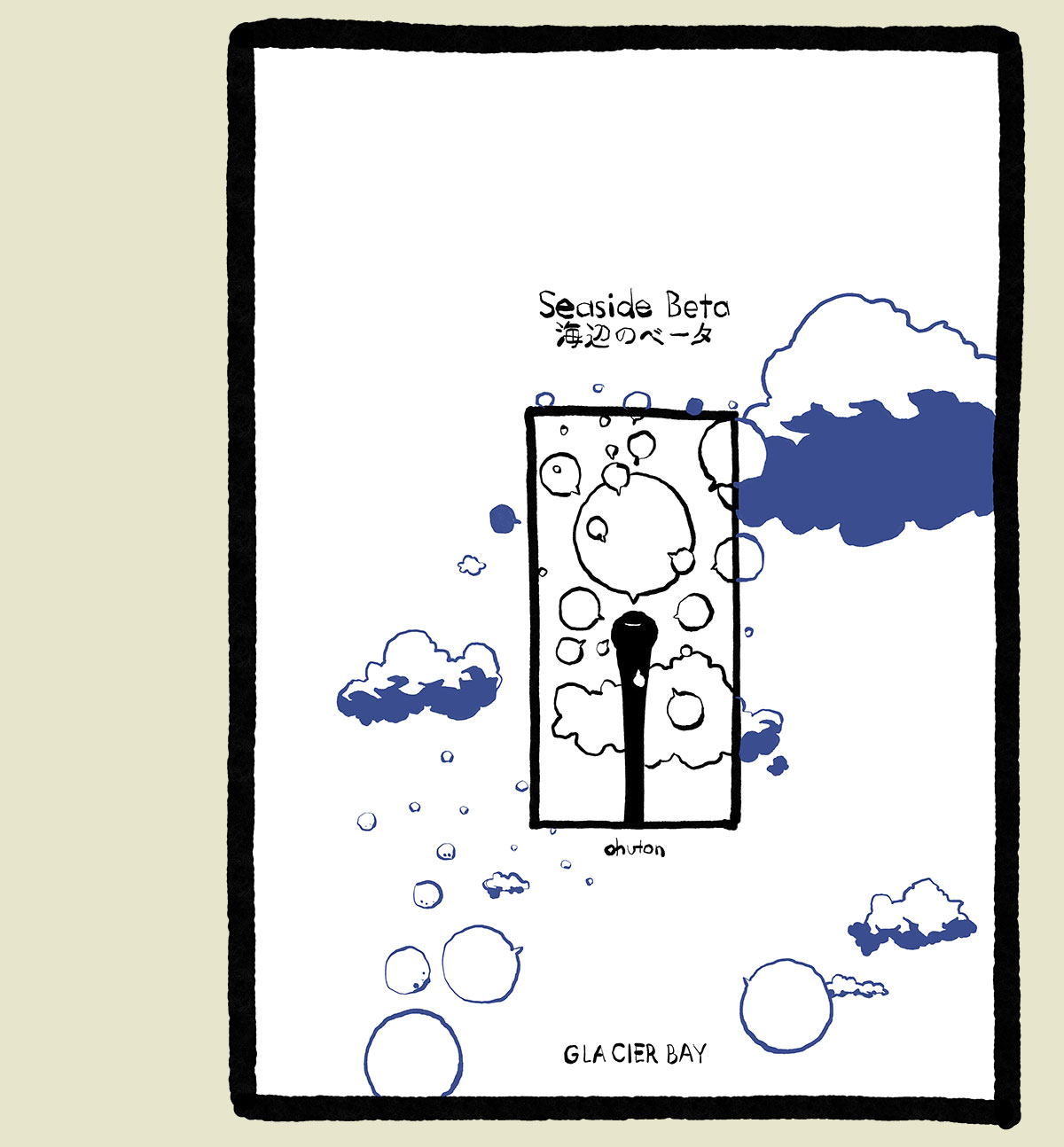

Seaside Beta

by ohuton (translated by RKP, lettered by Lauren Eldon)

260 pages

Published by Glacier Bay

Buy from Glacier Bay

Last year's top science-in-a-comic comic was easily Robin Cousin's The Phantom Scientist. This year's award unquestionably (for me) goes to Seaside Beta. Using Edwin Abbot's Flatland as a device (titled something else in the comic), the main characters (scientists) discuss the nature of their world, a manga world of black and white. They know the sky is blue, that trees are green, but none of them can see color at all, leading them to speculate a world where color is discernible. Oh, also, speech balloons are physical objects that appear split-moments before a person says something, then lingers for a little before floating away and dissolving. Like, you could bump your head on one.

This was an invigorating read, helped along by ohuton's art—which I've been a fan of for several years now. I've only read one other of their books (the excellent Dear Sara 1997) and it too was science-forward. I kind of hope this is their thing (them being a physicist, the bets are good), because I love reading science fiction comics from actual scientists instead of just fabulists or dabblers.

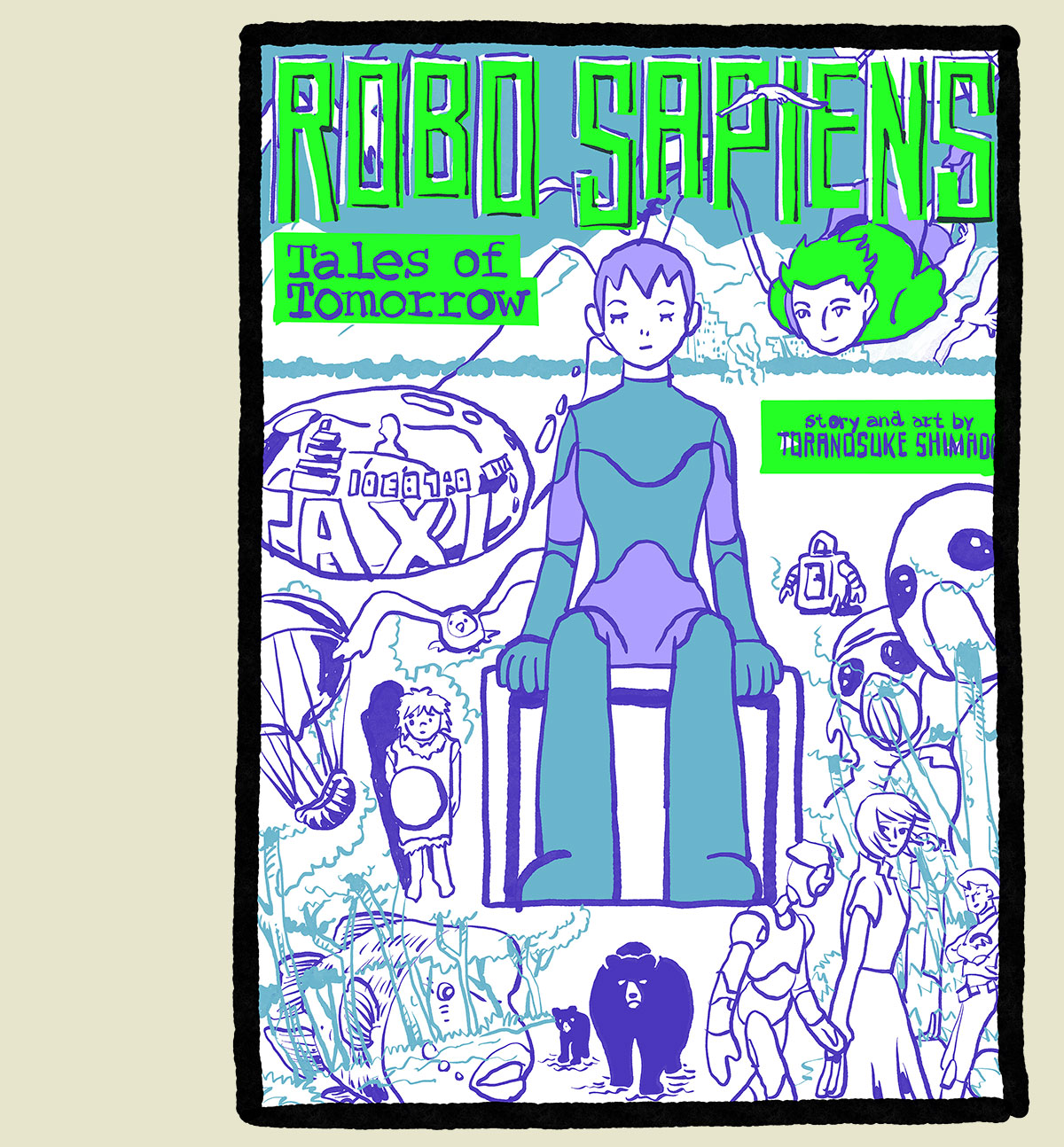

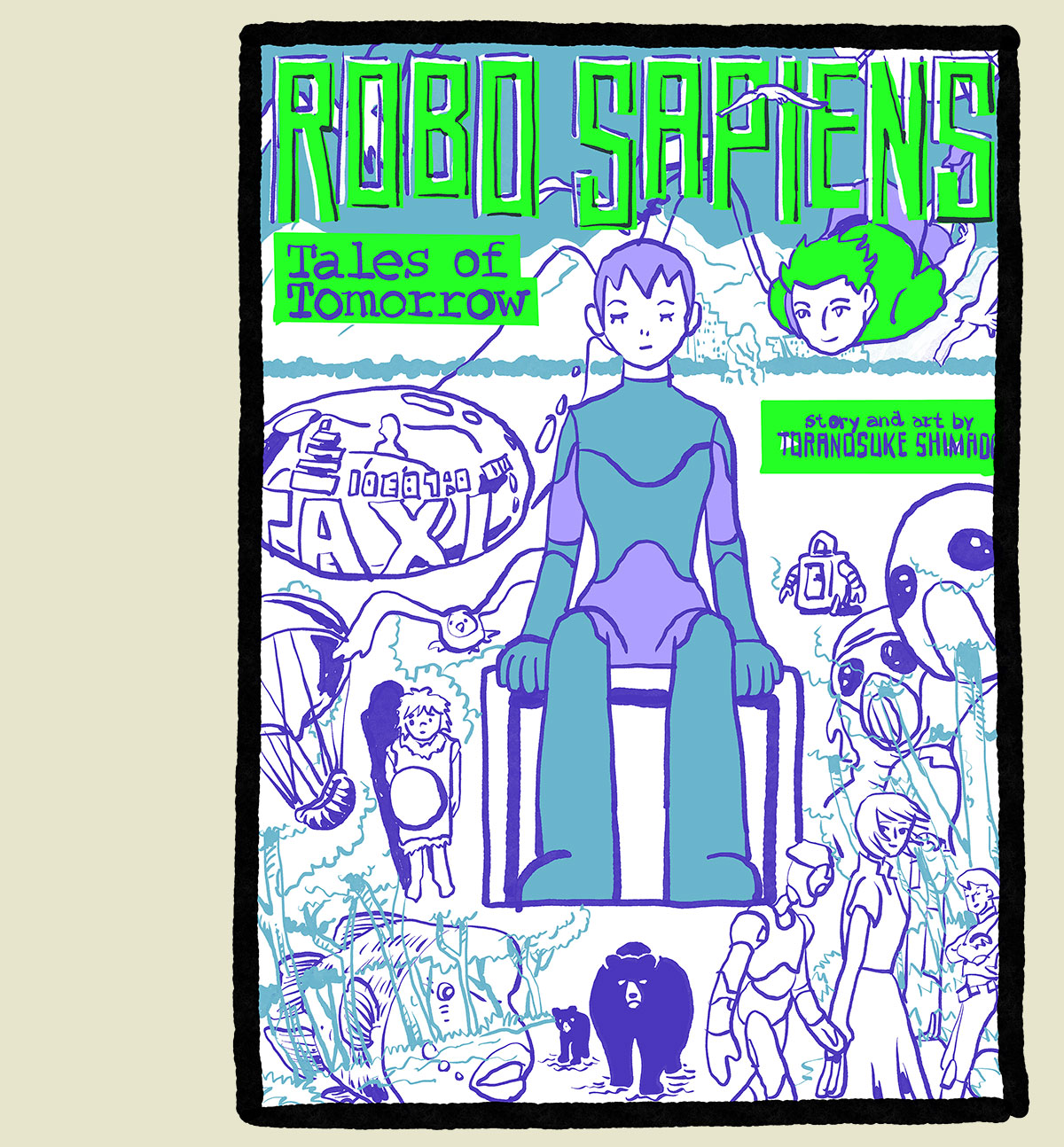

Robo Sapiens: Tales Of Tomorrow

by Toranosuke Shimada (translated by Adrienne Beck, lettered by Nicky Lim)

304 pages

Published by Seven Seas

ISBN: 1648275982 (Amazon)

This is a bit of roboganda that spools out like Matt Sheean and Malachi Ward's Ancestor, if you've read that, with a story spanning thousands and thousands of years. The story is structured in a string of short episodes—whose connection while felt very loosely at the front end gradually resolves into something chained together more obviously as we return again and again to the same four robot characters (with a couple guests along the way).

Here in the midst of our own current colossal AI fiascos, the hopeful, positive vibes that coalesce about the robotic protagonists felt a little hollow (a little too Rah Rah Robots!), but it's otherwise a fantastic story.

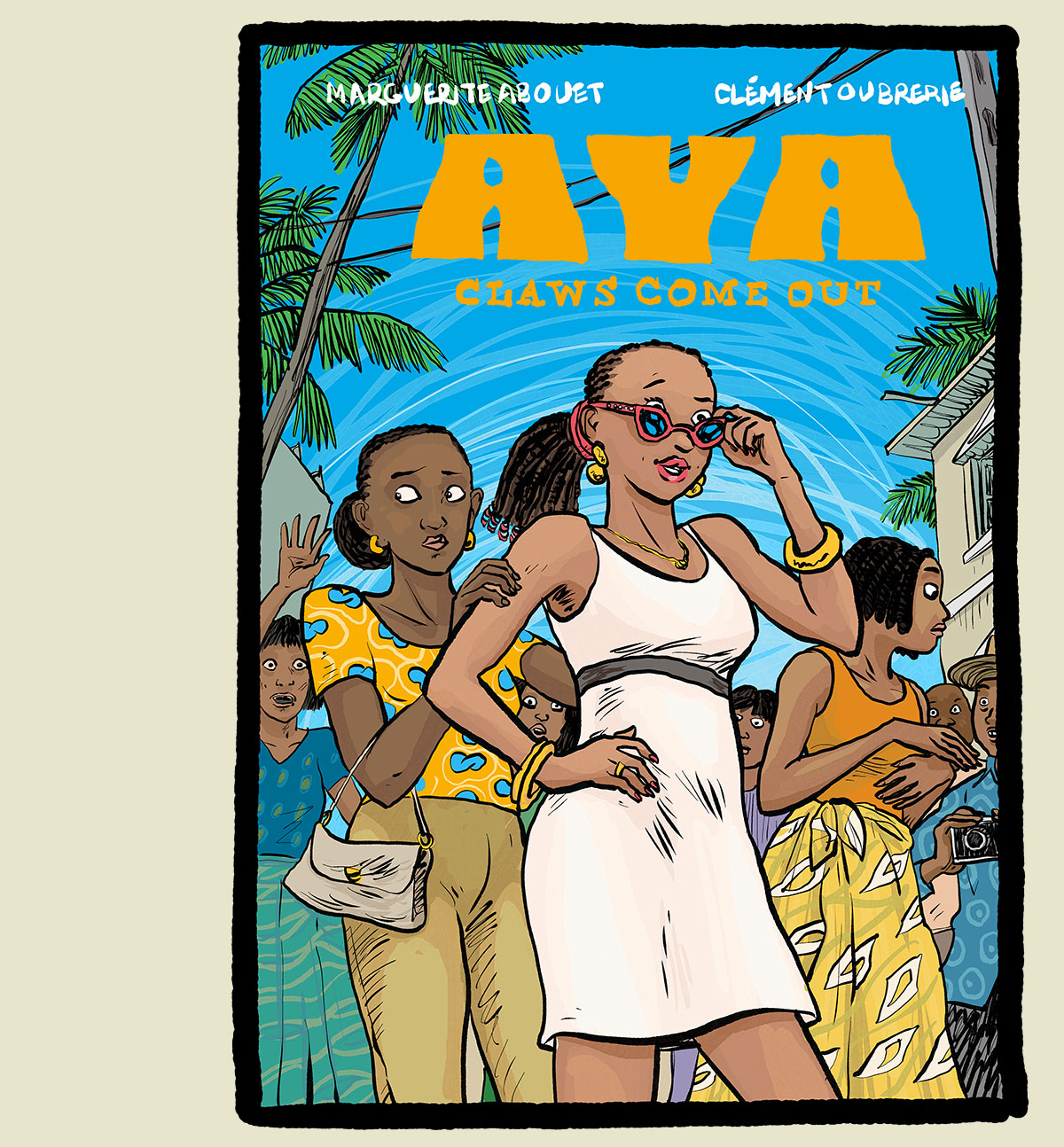

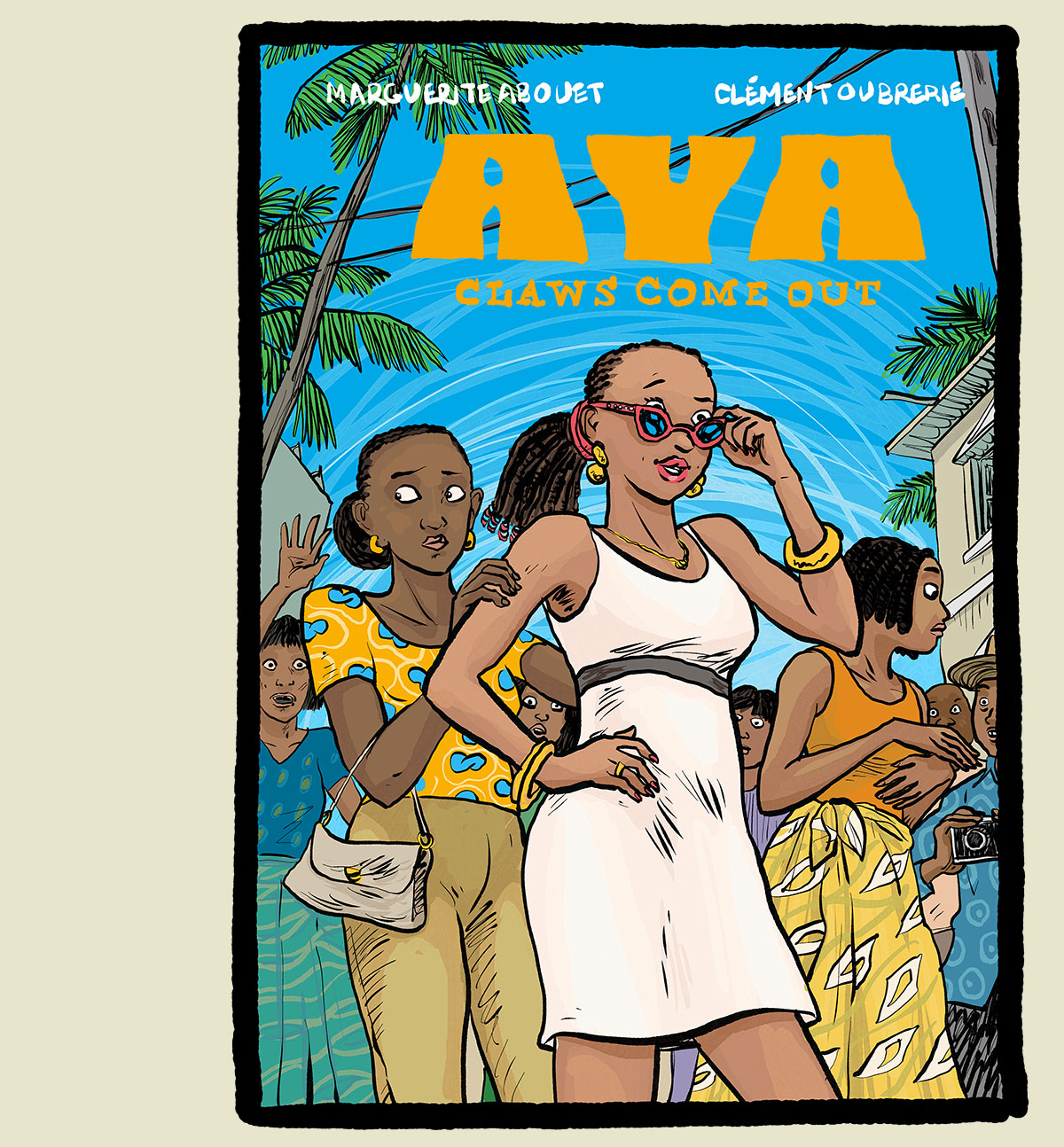

Aya: Claws Come Out

by Marguerite Abouet and Clément Oubrerie (translated by Edwidge Renée Dro)

128 pages

Published by Drawn & Quarterly

ISBN: 1770467017 (Amazon)

Aya is one of the coolest things. Taking place in Yopougon (colloquially known as Yop City), a suburb of Abidjan in Côte d'Ivoire, tells more than the story of Aya and her friends, acquaintances, rivals, and relations—on top of all that, it unveils a culture unique to a 20 year period and now lost to that era in history.

Between 1960 and 1980, Côte d'Ivoire thrived economically in a way that other newly independent African nations did not. Rather than drive out European populations and influences, those ties were welcomed and strengthened—and the wealth and assistance of France helped the economy boom in particular ways. For a little while at least.

Titular character Aya is about 20 years old, single, beautiful, wise, naive, and soberminded. This series features Aya, yes, but also tells the stories of Bintou and Adjoua and Hervé and Moussa and Félicité and Mamadou and Innocent and Gregoire and their families and more. It's a multi-multi-threaded narrative that's rambunctious and cacophonic and is really just a blast to read.

Aya is filled with people making bad but very human decisions, the kinds you or I make and have made regularly through our lives. It's also filled with proverbs. One of the idiosyncrasies of life in Cote d'Ivoire is that every is constantly using proverbs to confound, to make points, to comfort the abused, and to perpetrate savage burns. And everybody nods in understanding as if the speaker just QEDed the whole thing and shut it down. (And it's very amusing when one of the cast goes to France and does the same thing and these poor French people have no idea what's going on.)

While the storylines of Aya can get pretty serious (being sold into marriage, coming out of the closet in a culture where that would be dangerous, fake faith healers, rape and sexual assault, adultery, adultery, and more adultery, etc) the wit and barbs and lunacy keep the spirit steady with a buoyant sort of light-hearted cynicism.

One last thing I love about this series is that it doesn't preach or go in for didacticism. It 1) knows that people are people and will do good and bad things, often on the turn of a dime, and 2) presumes the reader intelligent enough to draw their own conclusions. So, for example, when Bintou comments on the rapist's poor looks wonders what gives the him the right to rape so many girls and then comments that "handsome helps," citing a girl who was raped by a cousin and made the best of it, Aya's response of "That's terrible!" is more focused on Bintou (who runs an advice/counseling business) betraying a confidence than on the woman's opinions about rapists (and we already know that Aya doesn't agree with her). It's just one example of hundreds in the book of normal people holding wonky opinions, just like in real life. In a period where a lot of our fiction reads as pedagogy, it's kind of refreshing to run into something that doesn't pull a GI Joe where "knowing is half the battle."

For a long time, Aya existed in the US as two volumes, each containing three of the original graphic albums in which the series originally appeared. The perhaps weirdly titled Claws Come Out is the first addition to the series in 12 years, and picks up right where we left off, now finding the cast well into the throes of 1980. There are now 896 pages of Aya to read and I cannot wait for there to be more.

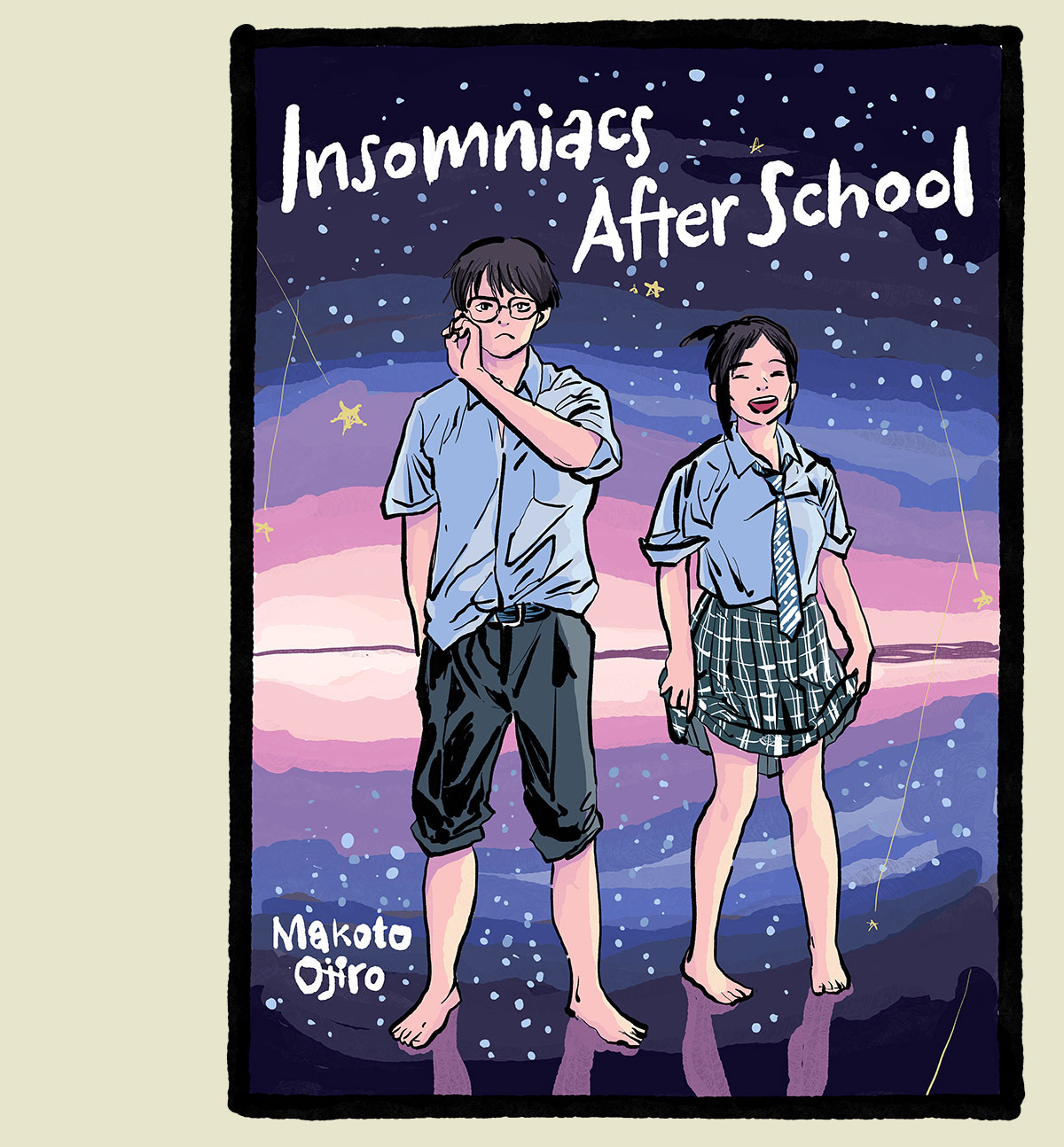

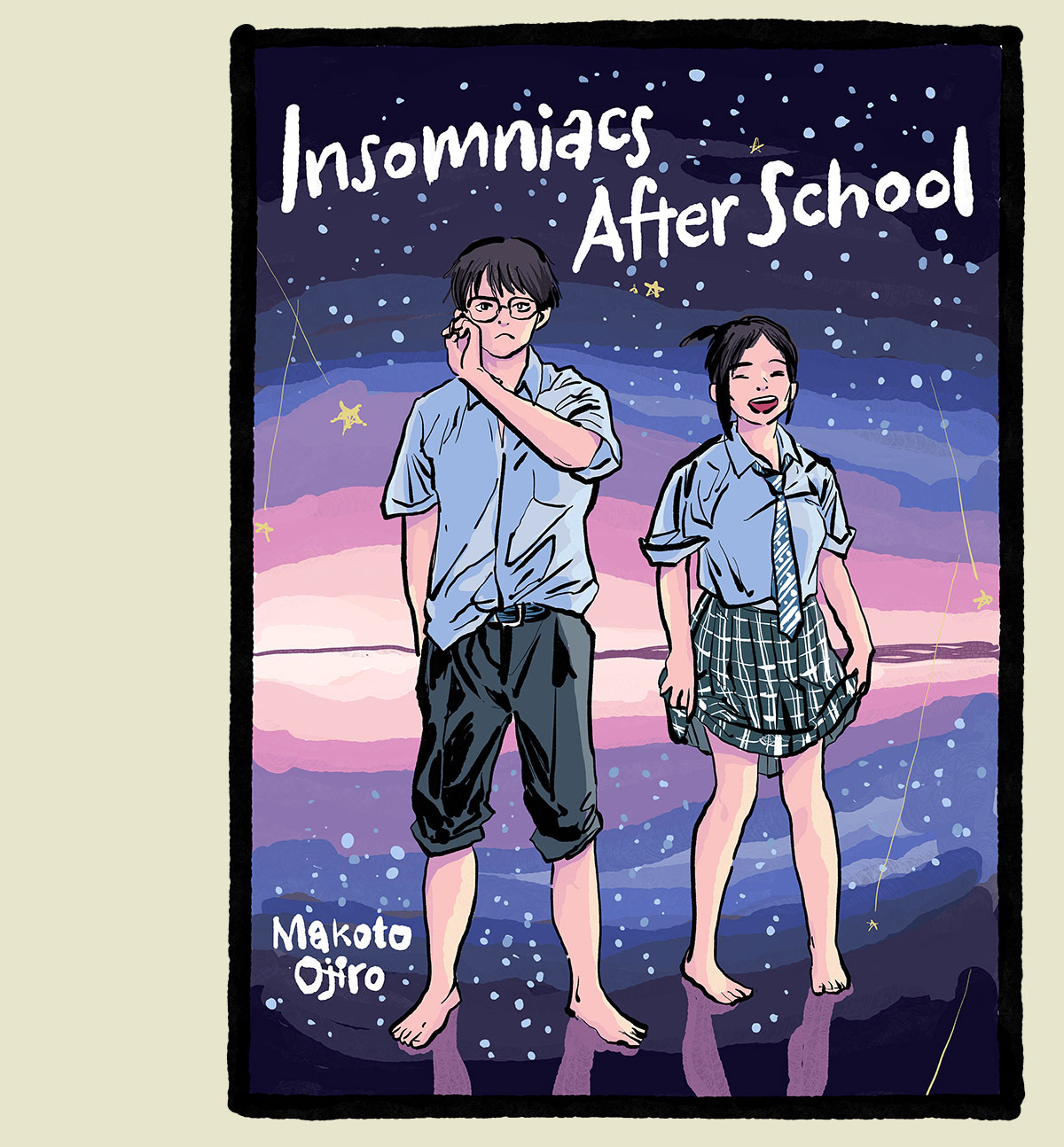

Insomniacs After School

by Makoto Ojiro (translated by Andria McKnight, lettered by Inori Fukuda Trant)

8+vols

Published by Viz

ISBN: 1974736571 (Amazon)

While the story is warm-hearted and it's just very nice to inhabit a world in which Nakami and Magari can find each other, gradually and persistently, the real star of this show about stars is Ojiro's art. She may be one of the best working cartoonists currently publishing.

Ojiro is a shockingly good drawer, not only well able to illustrate a cornucopia of expressions on very human looking faces, but leans deeply into compositions that underscore proximity in ways push and pull her narrative in ways that mere prose cannot and that we also don't see attempted in most comics. The reader feels the physicality of these two bodies, where they are both in actual material relation to each other but also in terms of how near or far those same two bodies feel they are. It's like how on weather apps, you'll get the actual temperature and then the "feels like" temperature.

I will follow Ojiro's comic-booking to the ends of the earth. No matter her subject, I will be there. I need this art in my life. But all the same? I'm glad that such a sweet story of human need and connection was my introduction to her work.

SupportProse I ReadNavel Gazing

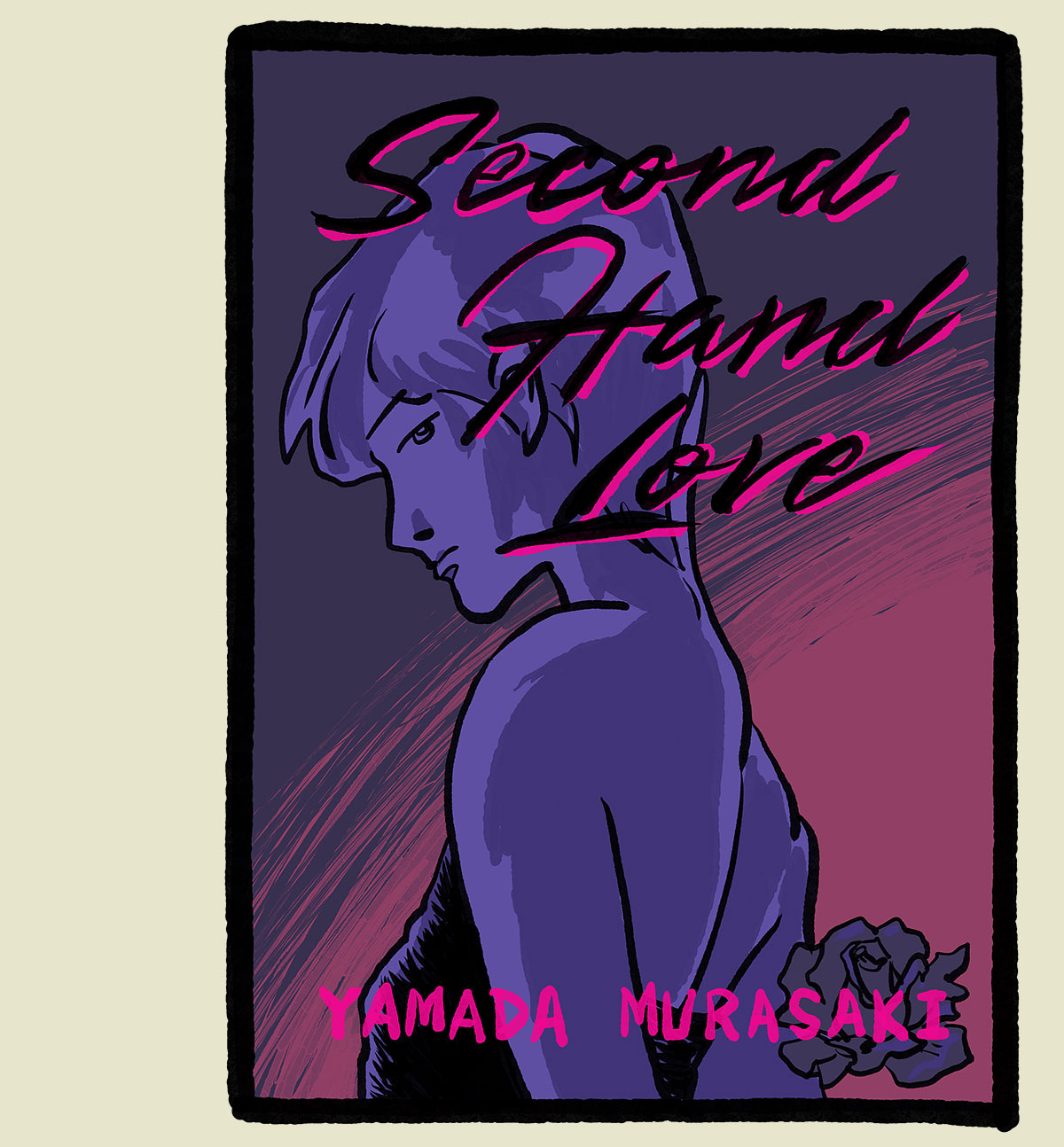

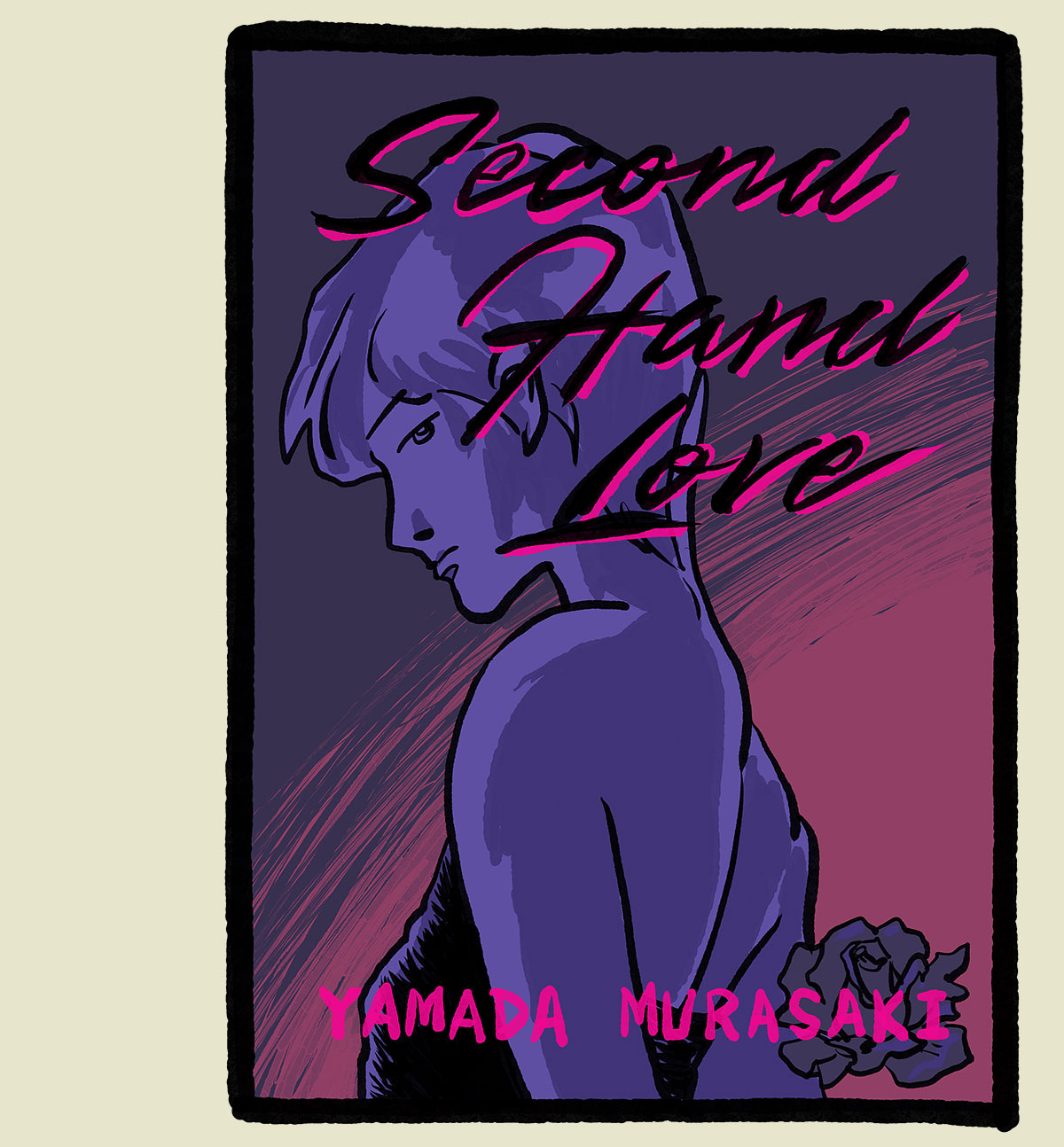

Second Hand Love

by Yamada Murasaki (translated by Ryan Holmberg, lettered by Sophie Yanow)

228 pages

Published by Drawn & Quarterly

ISBN: 1770467181 (Amazon)

My №2 pick from last year was Yamada's Talk To My Back, a vibrant, well-observed exploration of domestic prisons erected by marriage, motherhood, and a self-serving husband who finds a mistress. It's a phenomenal piece. Second Hand Love collects two stories, Blue Flame and Second Hand Love, each written from the perspective of the mistress in the marital triangle. It's thoughtful and sympathetic, inhabiting the place of the mistress with detail and care. While I prefer Talk To My Back, this works as a probably indispensable companion to the former book.

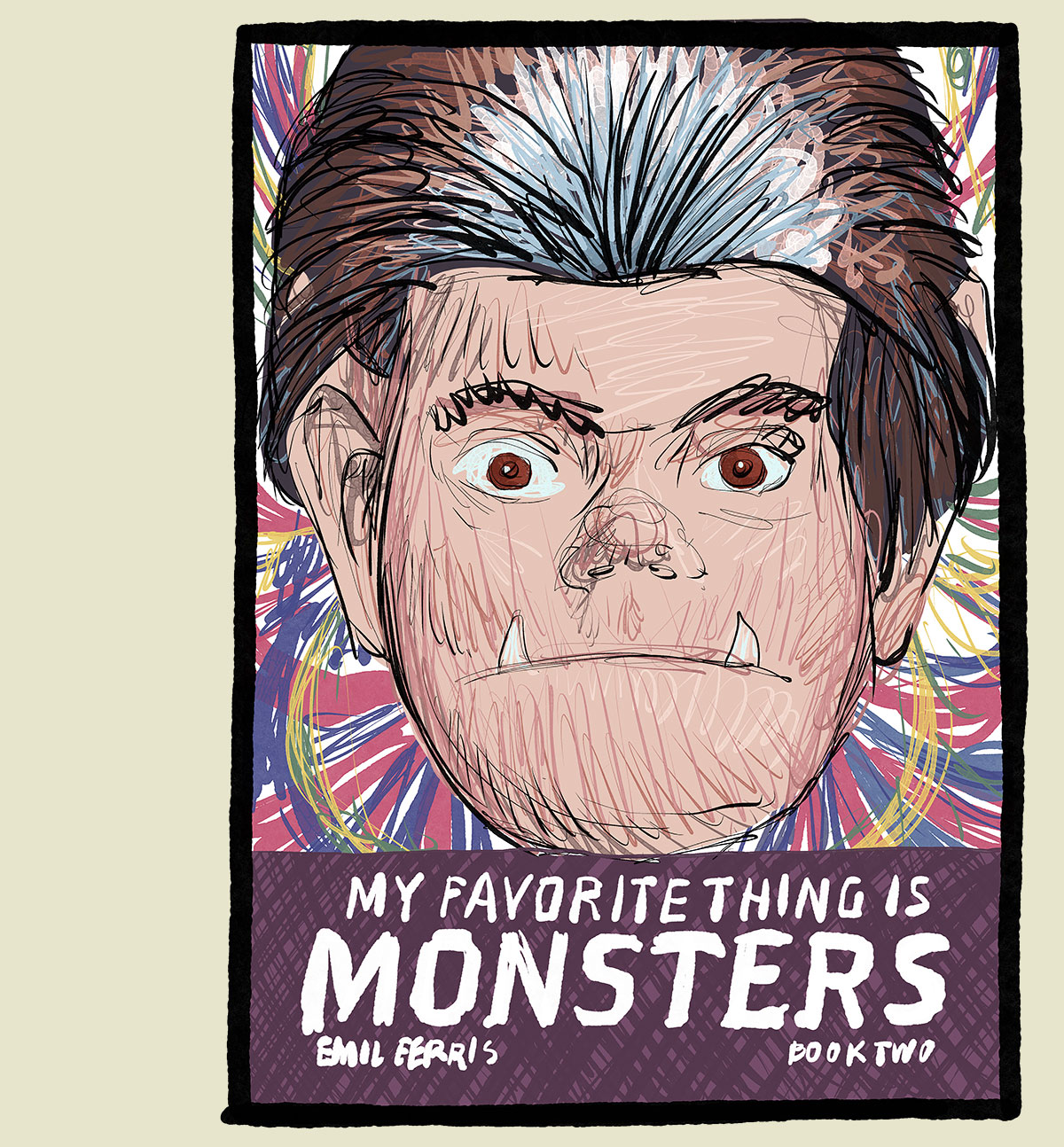

My Favorite Thing Is Monsters

by Emil Ferris

2+(?) vols

Published by Fantagraphics

ISBN: 1606999591 (Amazon)

It took me too long to really get the vibe that My Favorite Thing Is Monsters is laying down. I pinned it early on as a mystery/detective story and unfortunately let those genre presumption get their hooks into me. So I was constantly on edge for all the ways the book wasn't offering a satisfying vision of this thing it was never meant to be. Instead, two volumes in, it's pretty clearly chaotic crime, like if Stray Bullets were told from the vantage of a 10yo Virginia Applejack who latched onto Moto Hagio "Iguana Girl" vibes. Having had that revelation click suddenly into its revelation hole, I found myself enjoying volume 2 much more than I did volume 1.

As with Stray Bullets, Ferris's story of 1968 Chicago swirls and eddies with big characters and narrative anarchy. Any Friday night for these characters is more living than I'll likely do in my entire life. These waitresses, ventriloquists, jazz drummers, mobsters, prostitutes, lounge owners, madams, and gophers are all heaped up on each other, elbows bumping other elbows' business and nothing good will come of any of it—except for all the love and compassion you express along the way. Big hurts and big loves.

And then there are the kids. Abused, neglected, ignored, despised, and very occasionally, genuinely loved. Ferris's 10yo Karen underscores for us over and over that everyone is a monster (and her favorite thing is monsters), but some monsters are better monsters and some monsters are badder monsters. And I think Ferris lets us know that those adjectives flip back and forth in most cases.

MFTIM does some things very very well. The use of ballpoint pens (or possibly pen-emulating brushes) is awesome. Ferris' use of color here is almost incredible. As well, the bouncing around of the narrative and the discrete release of revelations works very well. On the other hand, page and panel flow can be awkward, and about 30% into the first volume I gave up trying to guess in which order I was meant to approach text blocks and balloons (and it doesn't get better in volume 2).

And while I've seen complaints about the story not wrapping up and plot bits seemingly being dropped, those complaints don't land for me. Sure, we only get trickles of the Sandy/ghost business. We still don't know what exactly happened with Anka either in wartime or in 1968 (though we do know who shot her). There are a host of other threads untied from Chugg's whereabouts to Silverberg's false alibi to Gronan's fall to what happened to Karen. While I believe we're expected to wait for at least a third volume, I'm approaching this like I do Stray Bullets. Do I need a wrap-up or am I here for the ride? This is chaos crime and can you imagine a world in which stories like this even ever have an end?

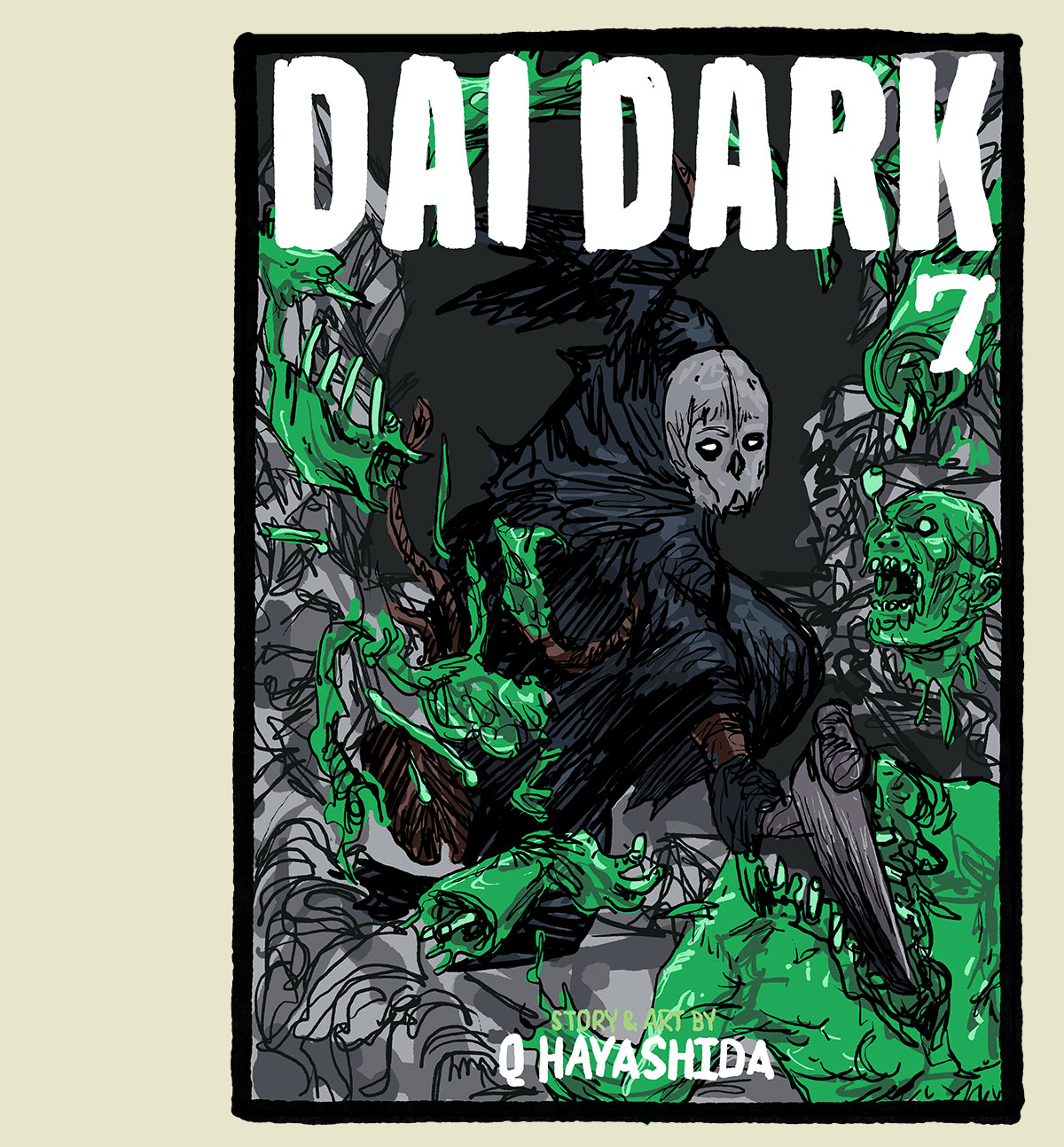

Dai Dark

by Q Hayashida (translated by Daniel Komen, lettered by Phil Christie)

7+ vols

Published by Seven Seas

ISBN: 1648271162 (Amazon)

The big question facing Dai Dark (is it as good as Dorohedoro??) isn't actually very much an important question at all. Dai Dark is good. Dai Dark is hilarious. Dai Dark is every bit as wild a revelation as Dorohedoro was. And now, as we find narrative tendrils from the one snaking into the other suggesting continuation rather than A Wholly New Work, the point becomes still more moot. Did you love Dorohedoro? Then you should be reading Dai Dark. Q Hayashida's humor is at its peak here and you want to be along for the dance.

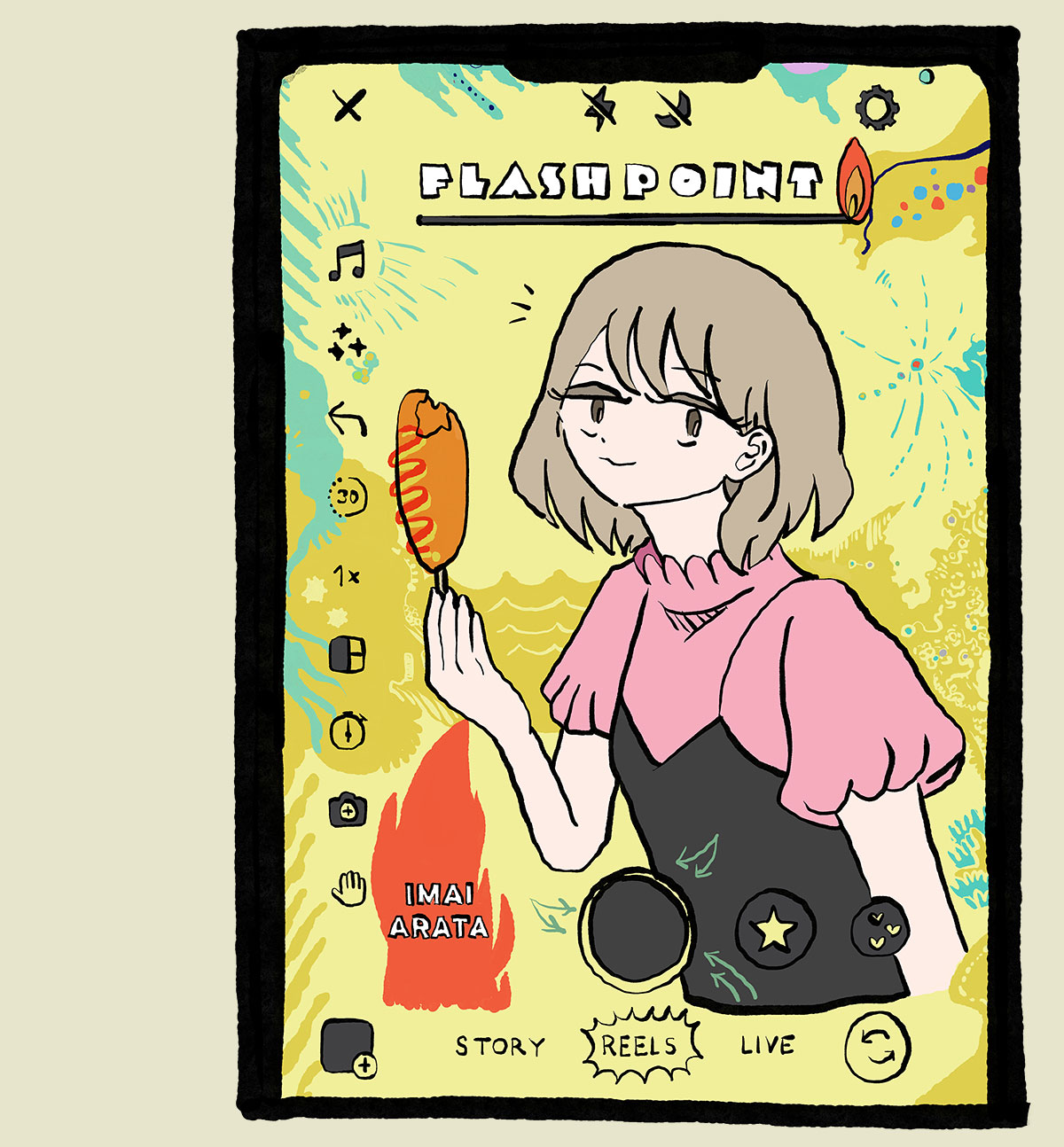

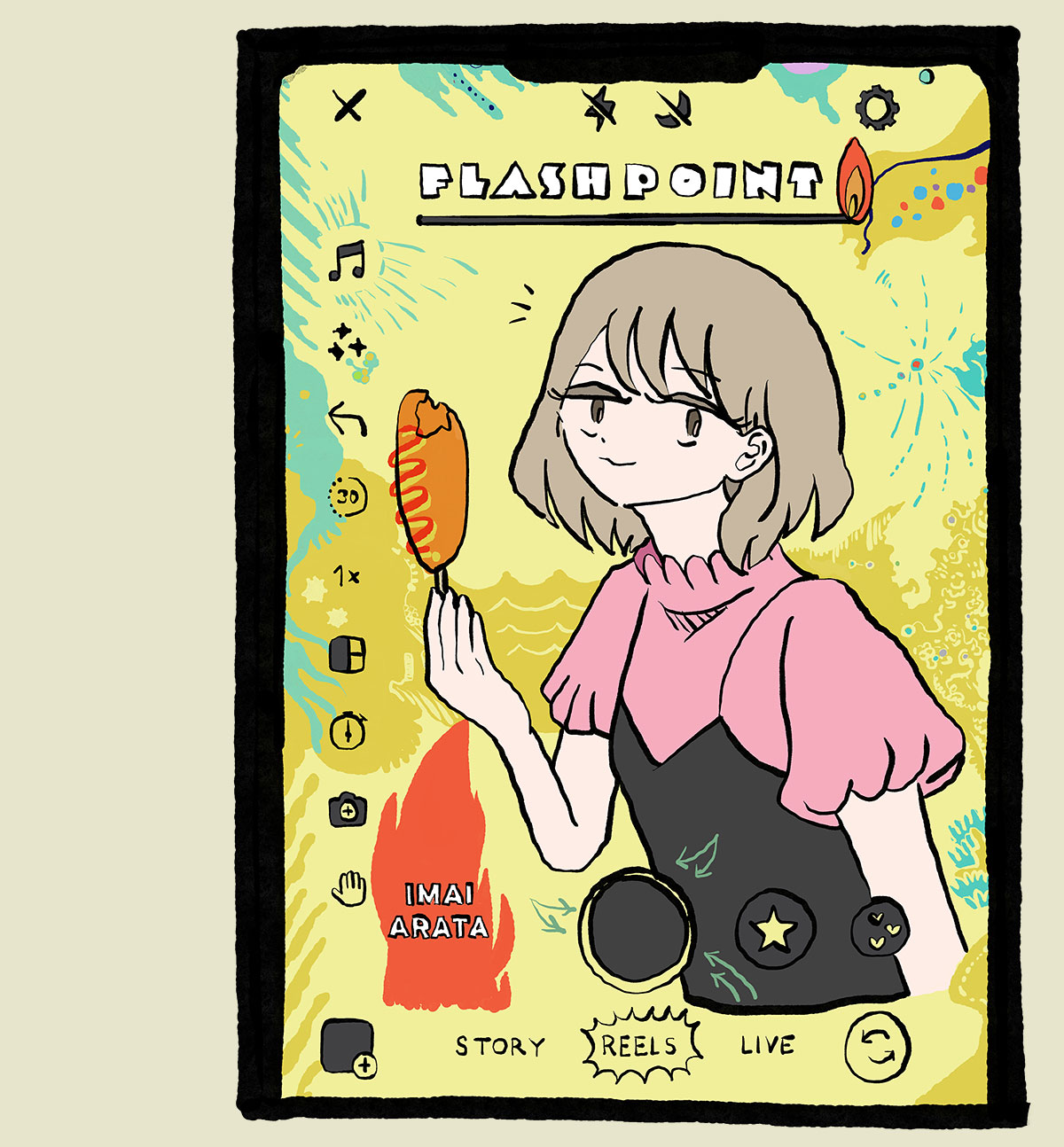

Flash Point

by Imai Arata (translated by Ryan Homberg, lettered by Lauren Eldon)

248 pages

Published by Glacier Bay

Buy from Glacier Bay

After reading Arata's earlier work, F, I knew this was a kid with pizazz and that I should expect something to excite me, but I didn't know to expect something so tonally different—as if Spiegelman followed up Maus with Yotsuba&!.

Flash Point, simply, is charming. It's funny, nutty, lightly jaded, kind of pleasantly unhinged. AND it features back-trouble solidarity, which is something I'll always celebrate.

Short synopsis: a truant girl accidentally goes viral for doing a fullbody F-P sign (YMCA-style) trying to get her friend to choose between fried chicken and pizza buns (I think it was fried chicken, I can't remember). Anyway, people see a Vine of it (or tiktok or IG reel or whatever) and think it's a hoot, and she amasses a following—as no-name weirdos tend to do for inexplicable reasons. A month or so later, she's passing by a political rally and decides to do the F-P sign (now her trademark) deep in the background of the rally, and while doing so, the speaker, former prime minister Abe is assassinated. Things spiral into crazytown from there, and I had a great time with the whole ride. This book was full of things I didn't expect—and that, it turns out, can be a very very good thing.

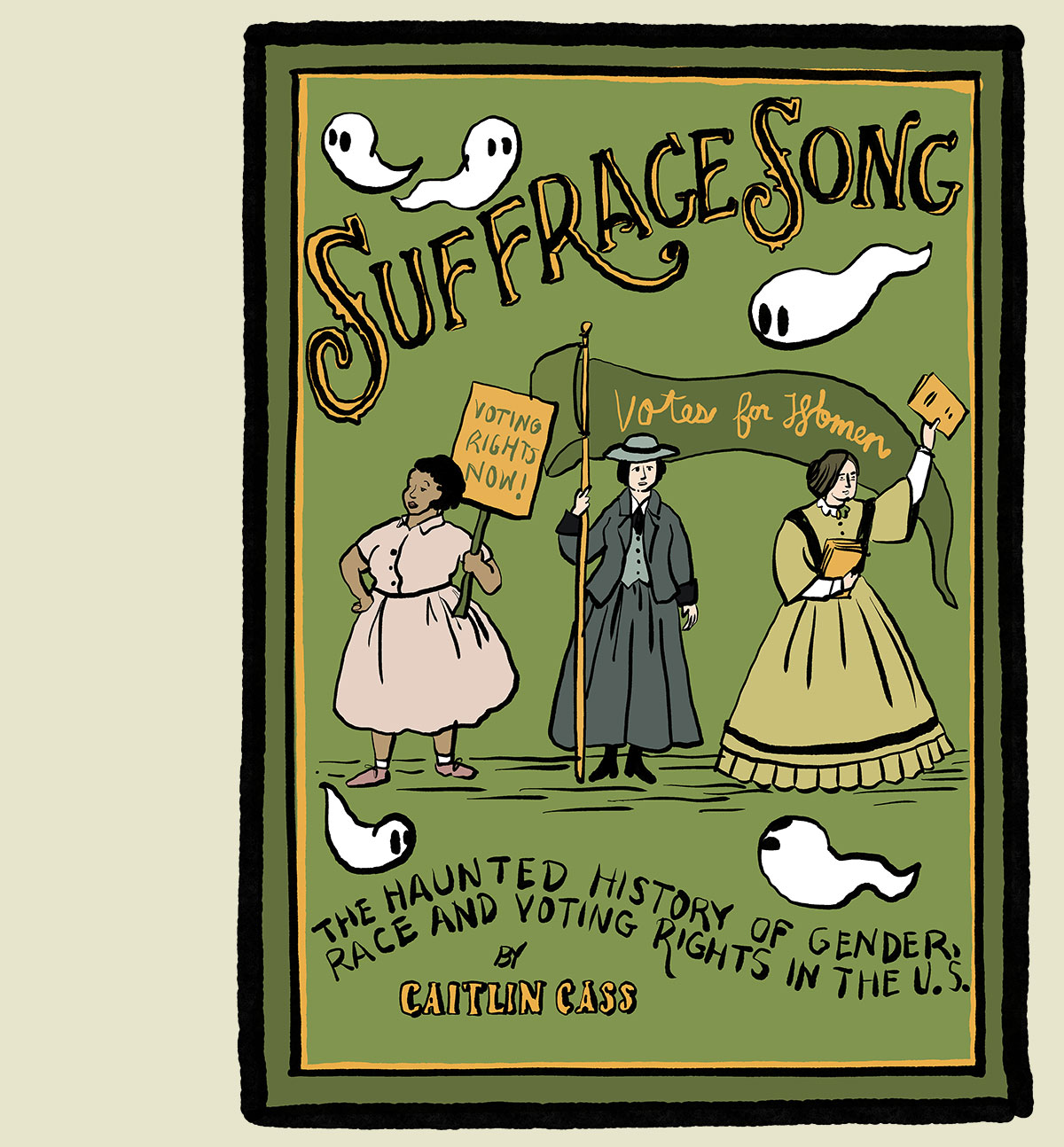

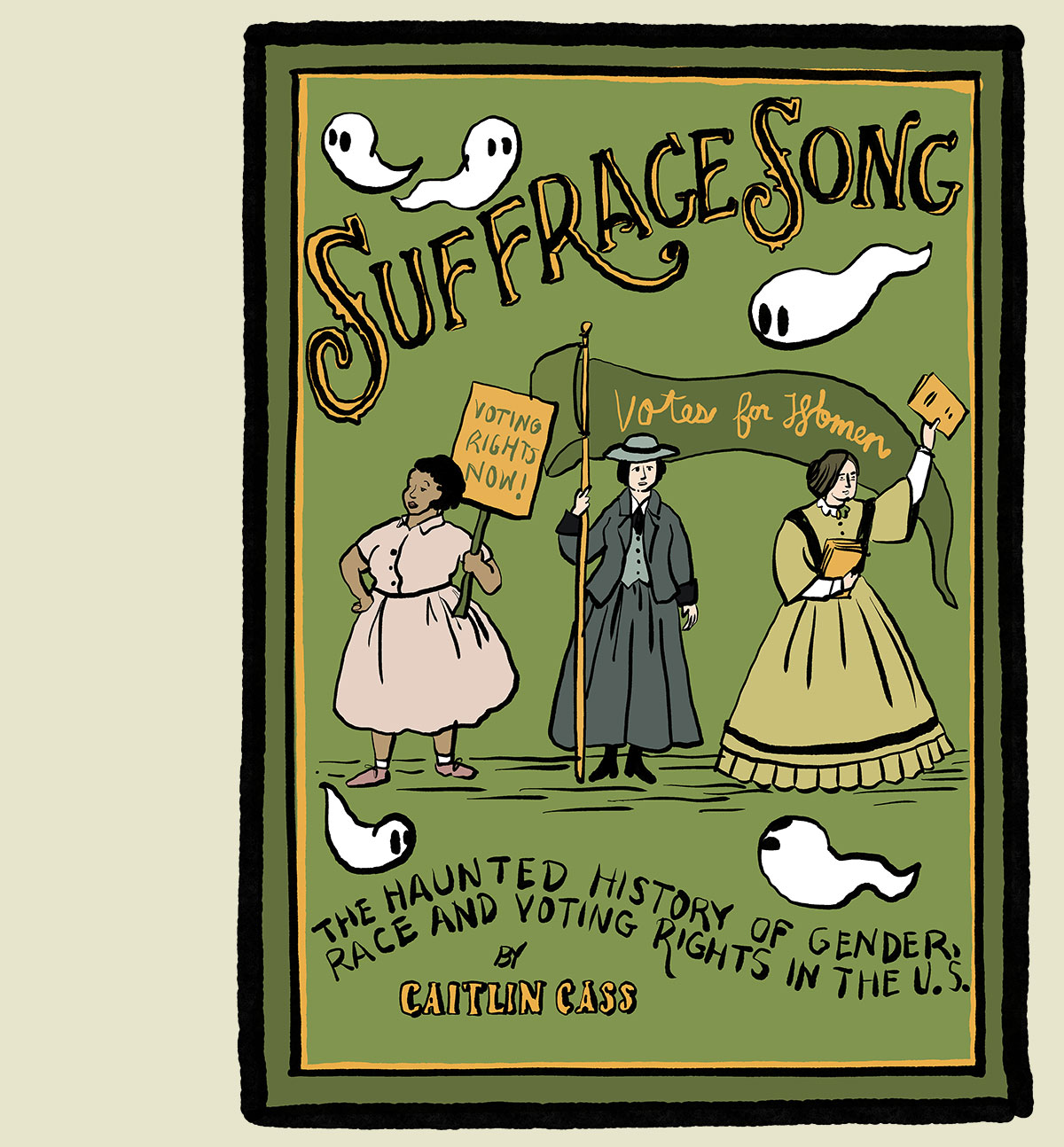

Suffrage Song

by Caitlin Cass

264 pages

Published by Fantagraphics

ISBN: 1683969332 (Amazon)

I've followed Cass through her bi-monthly zines since 2013. Her focus has been on the history of Western Civ with an eye toward folly (which meant she was usually writing about men and the dopey things they've done because that's generally who history has so far recorded) but around 2019, she nudged her focus toward women, and specifically the women aiming to give women a Voice. That began a so far five-year project cataloguing the glories and follies of the women who fought for voting rights. (Much of the folly comes from the white suffragists absolutely throwing women of color under the bus if that meant white women could vote.)

Suffrage Song collects those zines in a beautiful hardbound edition that finally makes her work more readily available. It's clearly been a lot of work because Cass's original zines are in all kinds of shapes, sizes, and formats (several were posters)—so here they've been cut up and renegotiated in order to fit on the page. Apart from a new prologue and epilogue bookending the collection with Cass's own personal thoughts on the collection and why looking into the past is powerful in light of current struggles, I've read all of this before and can readily recommend it as a tapestry that weaves disparate stories into a vibrant history. I'm also excited to read it again&8212;excited enough that I'll be assigning it as part of our high school's Graphic Novels As Lit unit. Cass's book feels particularly fitting as various subcultural strata increasingly view the idea of women voting (or voting independent of their husband's wishes) with skepticism or derision.

Lastman

by Balak, Michaël Sanlaville, and Bastien Vivès (translated by Edward Gauvin, lettered by Andworld Design)

6 vols

Published by Image

ISBN: 1534322299 (Amazon)

Holy smokes, what a wait for what a ride.

In 2015 and 16, First Second published the first half of Lastman and then suddenly stopped. The deal with Casterman (the French publisher) fell apart for Reasons, and so we were left on a literal cliffhanger with young Adrian Velba hanging on the edge of a cliff. Desperate to know more, I bought the remaining French volumes as they came out (I don't speak French) and picked my way through with the help of Google translate and translation forums to help tackle idioms. It was a sucky sucky experience and I regretted sleeping through three years of highschool French. Finally, in 2022, Skybound (through Image) began reprinting the series (now translated by the able Edward Gauvin; you may know him from Fantagraphics translations such as Tardi's books), each of their volumes containing two of the original tomes. I skipped on the first three since I already had them all in First Second form (though I would like to get them to compare translation choices), but grabbed vols 4-6 to finish the series off in a competent translation (I've no illusions about the inadequacy of my Google translation). It was worth the wait.

Lastman is a pulse-pounder—stem to stern adventure—and it refuses to sit still. It begins a battler with a magical tournament arc, then shifts into seedy urban celebrity-driven mob infighting, then there's a timeskip at the halfway point, then air pirates, and then...

Things had been gradually getting weird for a while, but then everything goes wrong and wrong and wronger than wrong—not in terms of narrative value but for our characters. Things get dire and the thrills mount. There are just deserts and there are horrific tragedies, catharsis and anguish. It was a wonderful ride and I only wish the tv series prequel were available in the US because there are one or two moments in the book that assume familiarity with the show. It doesn't ruin the book, but it is a small diminishment. And certain moments would have landed better had I seen the show.

(One very funny thing: with vol 1 and 2, since I thought I'd grokked the nature of the book, I long ago placed it on my Kids Recommendations for, I think, upper elementary age. That turned out to be a hilariously poor choice. My kids have read vols 1 and 2 (just vol 1 in the Image edition) so many times the covers are tattered and are desperate for more. I keep telling them, "Eh, when you're a little older." My eldest is 15yo and I'm nearly at the point where I think she could manage it okay.)

Carl & The Magic Coin

by Akil Wilson

19 pages

Self-published

Read here

This one came out of the blue for me. I was entirely unfamiliar with Wilson or their work. I saw them like one of my posts on Bluesky, checked their profile, saw they made comics, followed the link, clicked on Carl & The Magic Coin, and in minutes found myself sitting in Starbucks with burning, weepy eyes, touched in my heart's heart. That's amazing comics. Just magic.

Sunday

by Olivier Schrauwen

474 pages

Published by Fantagraphics

ISBN: 1683969677 (Amazon)

Sunday is one of those books that falls into that uncomfortable category of comics I didn't enjoy and will never read again but was good comics and has plenty of page that I'll reference again. Should it be here on this list then? Maybe so, maybe not. It's worth drawing attention to though at any rate.

This is one of those high-concept books that we get every now and then that sparks our comics-loving souls—even if we don't particularly care for the project as a whole. Something like Here or Soft City. Sunday is aactually very much like one of my favorite novels of 2024, Mark Haber's Lesser Ruins, in which the entire book is a man's thoughts as he consumes four perfect cups of gourmet coffee. The difference is that Mark Haber's main character is, even if entirely pretentious, a man of interesting thoughts. Schrauren's Thibault, however, is quite a bit less of that. The entirety of the project rests on how well Schrauren can visually modualte a very boring day with very boring thoughts and the world outside of Thibault's—and honestly, he's more successful than not.

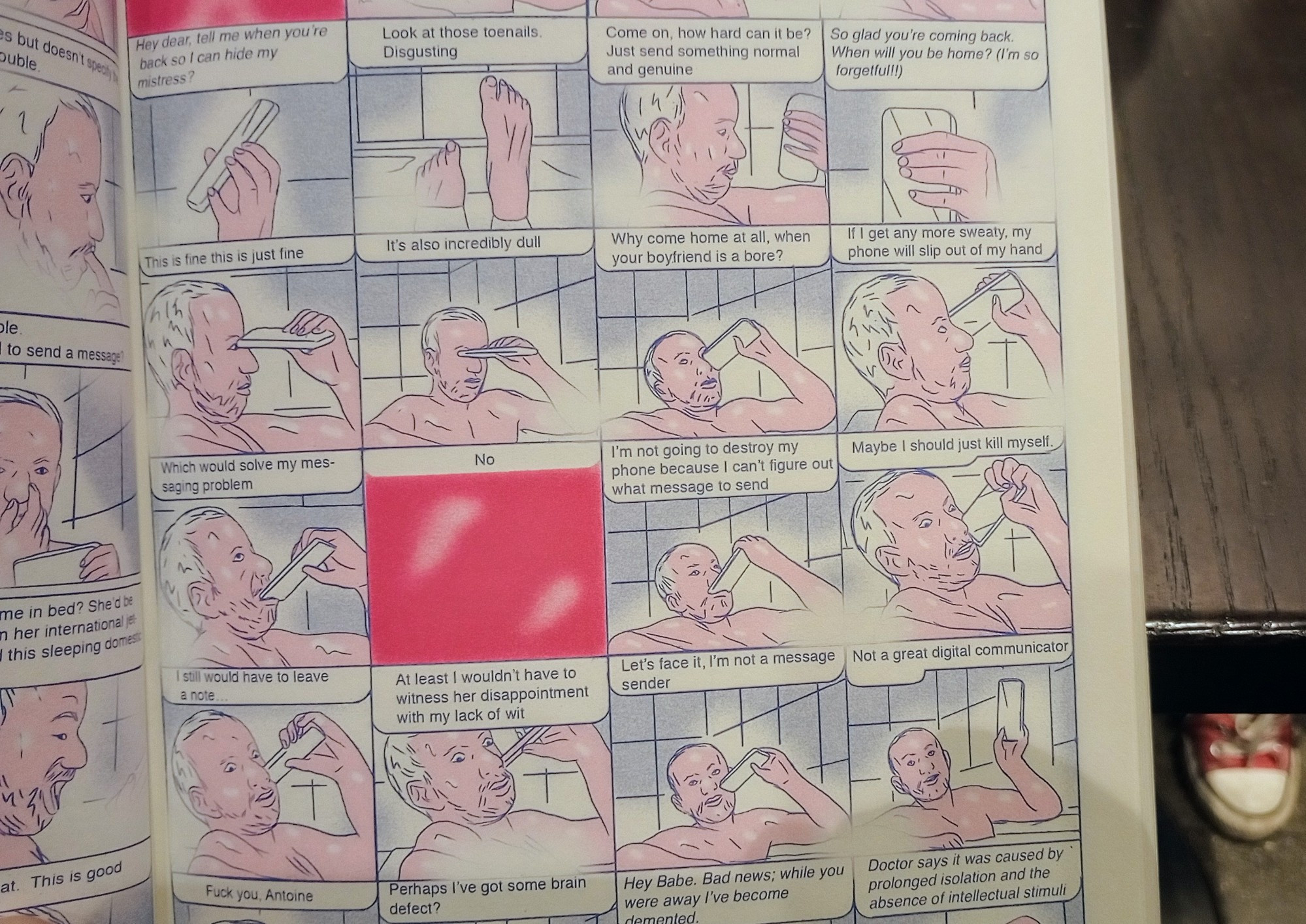

While I didn't enjoy Sunday, there were moments that were so perfectly well-observed that I let out a laugh of recognition. Scenes like Thibault moving around his face while taking a bath:

The Quest For The Missing Girl

by Jiro Taniguchi (translated by )

333 pages

Published by Fanfare/Ponent Mon

ISBN: 8496427471 (Amazon)

I'd stupidly sat too long on this one. A fan of Taniguchi's work since first reading The Walking Man (in, what, 2006?), I've since devoured nearly everything I've found of his published in English. With a few outliers. Books that seemed inconsequential or books I'd been warned off. I skipped Japan As Viewed by 17 Creators simply because a single short in an anthology didn't entice me. I skipped The Times Of Botchan because I'd read that its nuances were largely indepherable to Westerners with less than specialized sense of Japanese history. And I'd skipped The Quest For The Missing Girl because I'd heard it was weak, unfulfilling.

I don't know who told me that and kept me off this book for more than a decade, but frankly, I think they were some kind of idiot. Or they just had a really bad day when they read it.

Because man, Missing Girl was a joy. Just a short, sharp bit of fun thrills and detectiveness that occasionally looks like Kurosawa's High And Low. There's a girl who's missing (shocker), kidnapped and held without ransom. There's her "uncle," a mountain climber and best friend of her departed dad, who died on a climb that the "uncle" could have taken part in and changed fate (maybe!). There's her uncle's investigation into just what his friend's daughter was getting up to after school and his utter inability to navigate big city night life in a way that will get cynical kids to open up to. There's the mom who the "uncle" wanted to marry that just wants her daughter back. And there's the hilarious way that Taniguchi shoves mountain climbing into the finale. Absolutely bonkers and perfect.

Ismyre: Disciples Of The Soil

by B. Mure

5+ vols

Published by Avery Hill

ISBN: 191039579X (Amazon)

I believe Mure's Ismyre collection of books will conclude with a sixth volume, but what do I know. At the least, things are coming to a head, and while vols 1-4 can be approached as relatively standalone, vol 5 is the only one to end on a cliffhanger.

While generally, characters don't overlap between vols, Disciples Of The Soil brings back the main two from vol 1 as well as the main character from vol 3 (who also appeared in vol 4). Because of this lack of a steady cast, I'd originally thought of the Ismyre books as roughly unconnected stories within a single world (kind of like all the Fallout gmaes), on this reading (my first to approach them all at once), it was clear that they are through their disparate tellings tracing the story of the nation of Ismyre over a decade or so.

B. Mure does a wonderful job making his fictional playground into a breathing, throbbing entity, one heavily fraught with politics, turmoil, magic, and a growing public rage. There are murders. There are protests. There are governmental shifts. There are the elites, the workers, the artists, the faithful, the wizards—and a coming apocalypse that anyone could see coming.

The latest book, Disciples Of The Soil, is also the first to treat death less as a mystery to be solved and more like the damned tragic loss that it is. I've been a fan of these books since discovering them around the release of volume 2, and I'm anxious for the finale (?) later this year (?).

SupportProse I ReadNavel Gazing

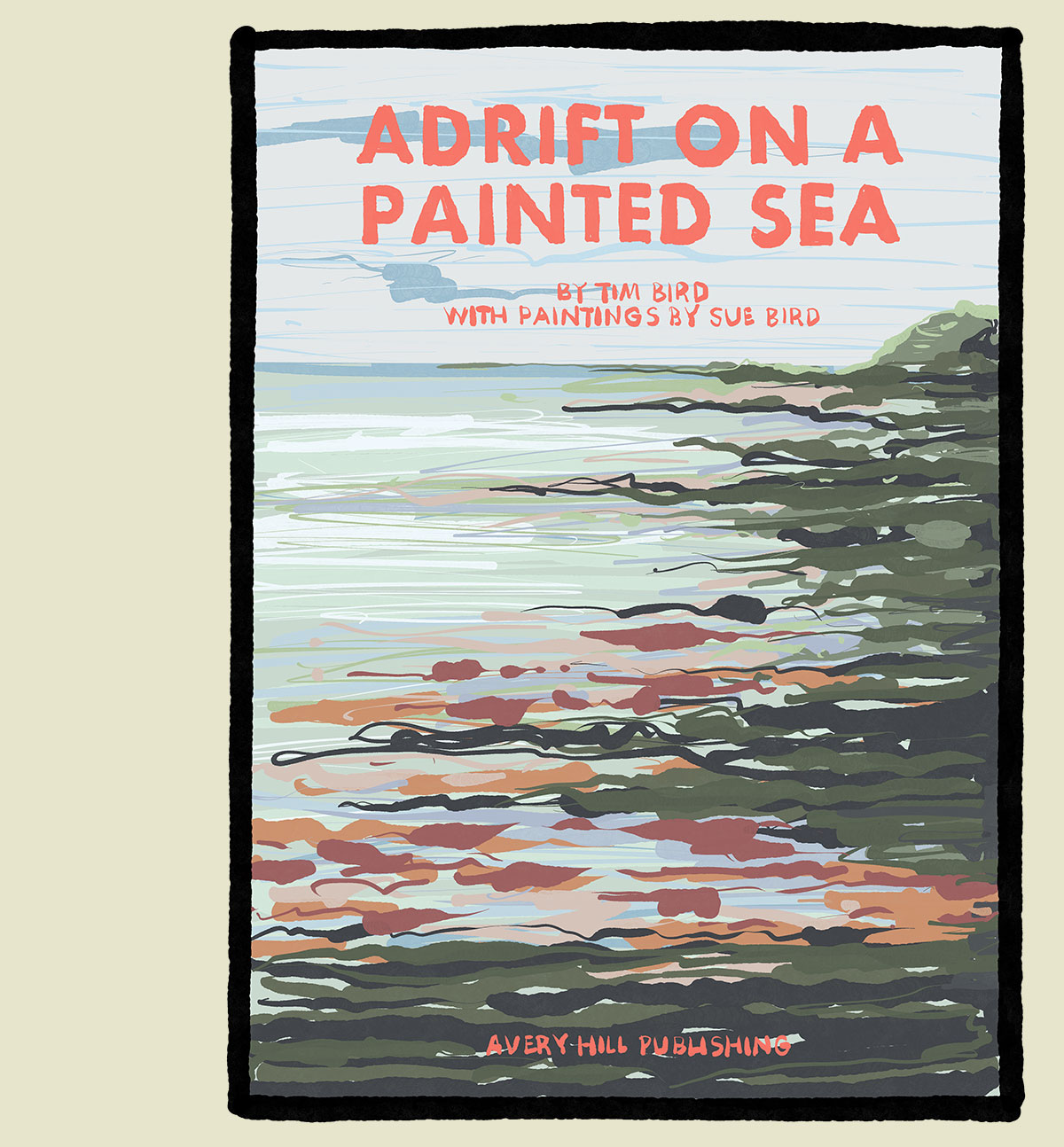

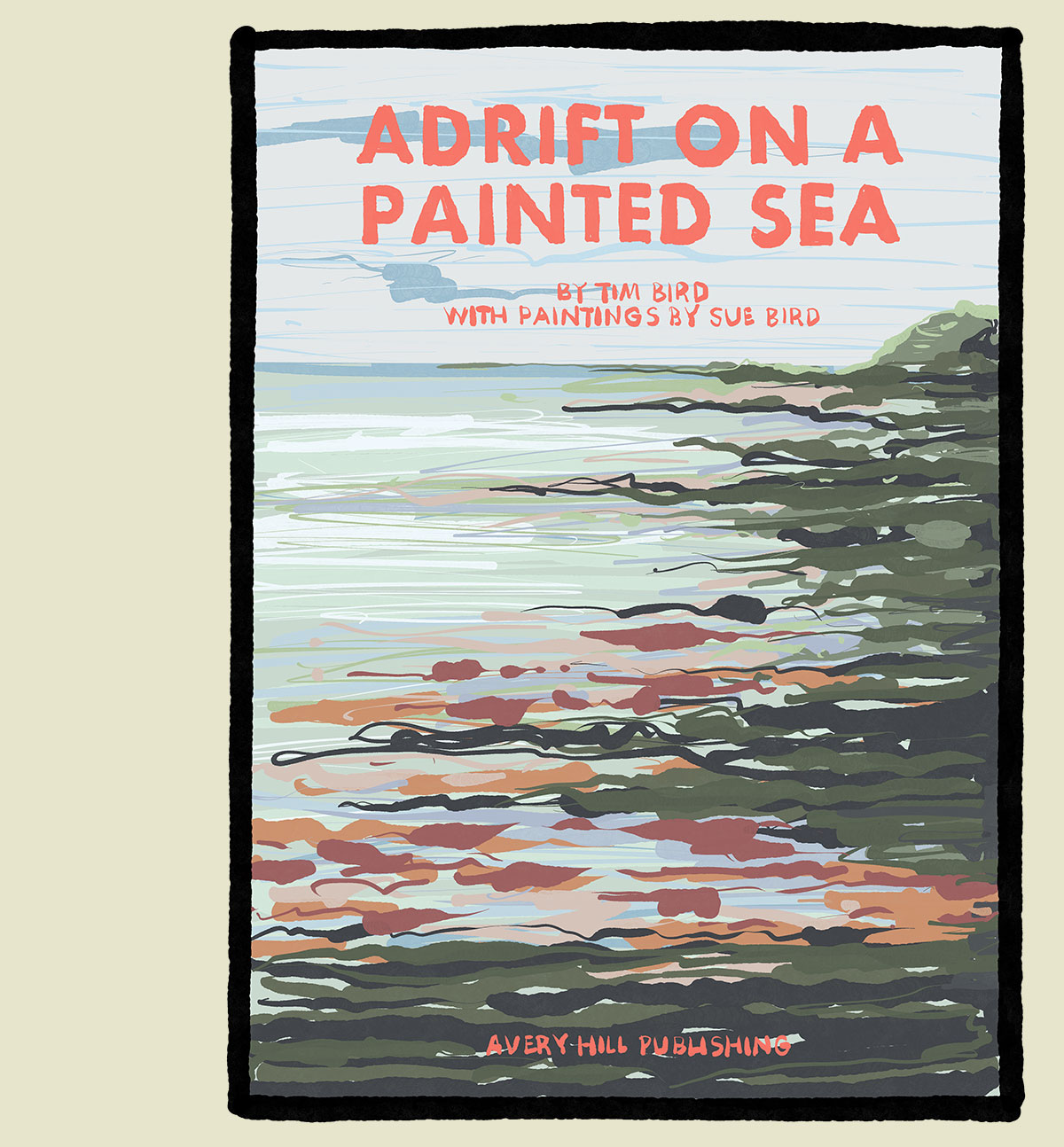

Adrift On A Painted Sea

by Tim Bird with paintings by Sue Bird

84 pages

Published by Avery Hill

ISBN: 191039582X (Amazon)

Bird intermixes panels of his mother's art over the years with his own cartooning, giving a short 84-page reflection his mother's life and what meaning remains. Sections of the story are broken up by mysterious nautical weather maps and announcements and, of course, that all comes together by book's end in a satisfying, revelatory way. Bird often draws scenes depicted in his mother's paintings to good effect, inhabiting his mother's world via his own cartooning. This is the kind of book that the term "poignant" was built to describe. It's quiet, brisk, thoughtful. This is not Craig Thompson struggling with parents he loves but thinks were kind of crap parents. This is just a guy who misses his mom and wants everyone to know what a wonder this woman away off in Yorkshire truly was.

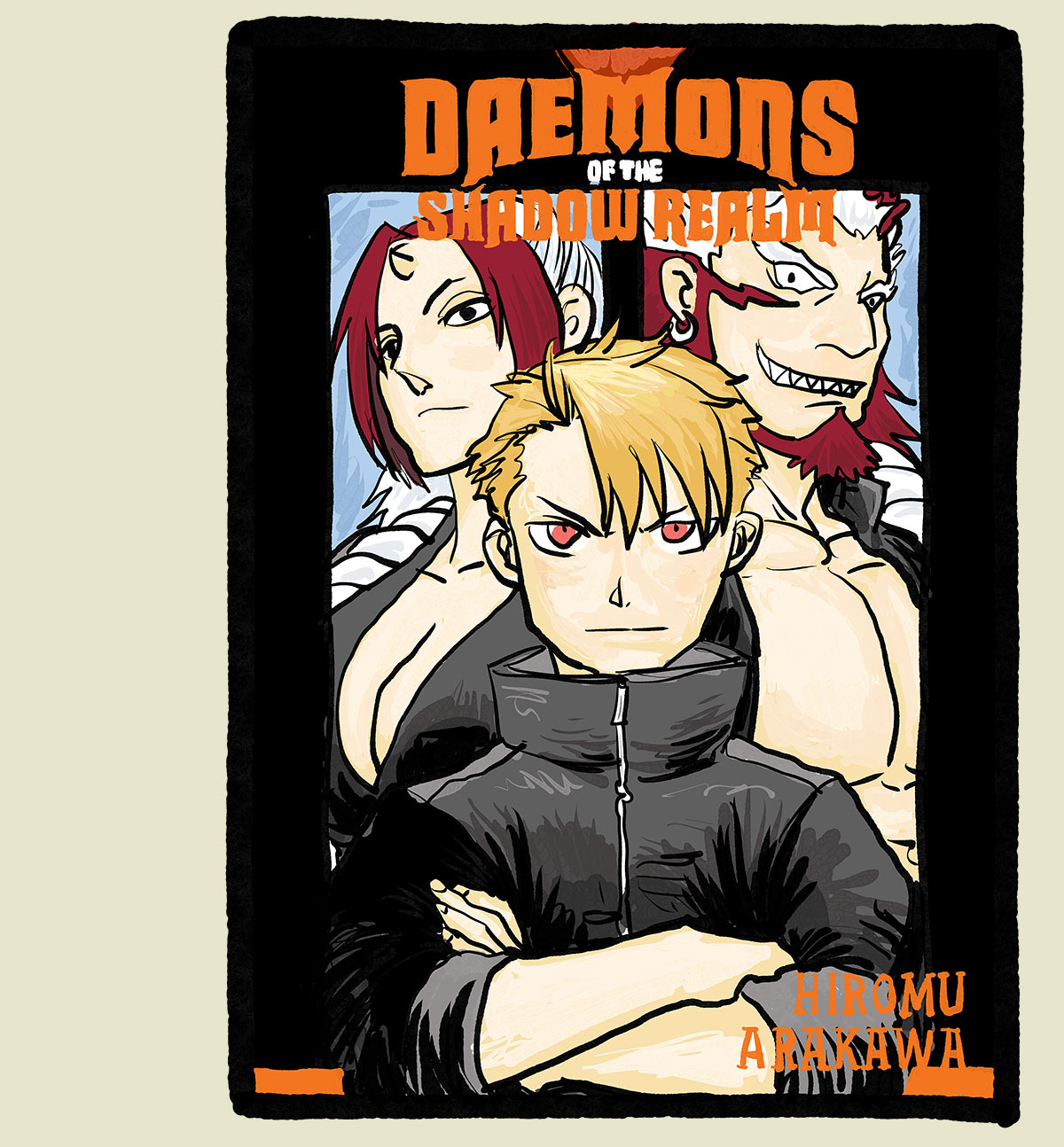

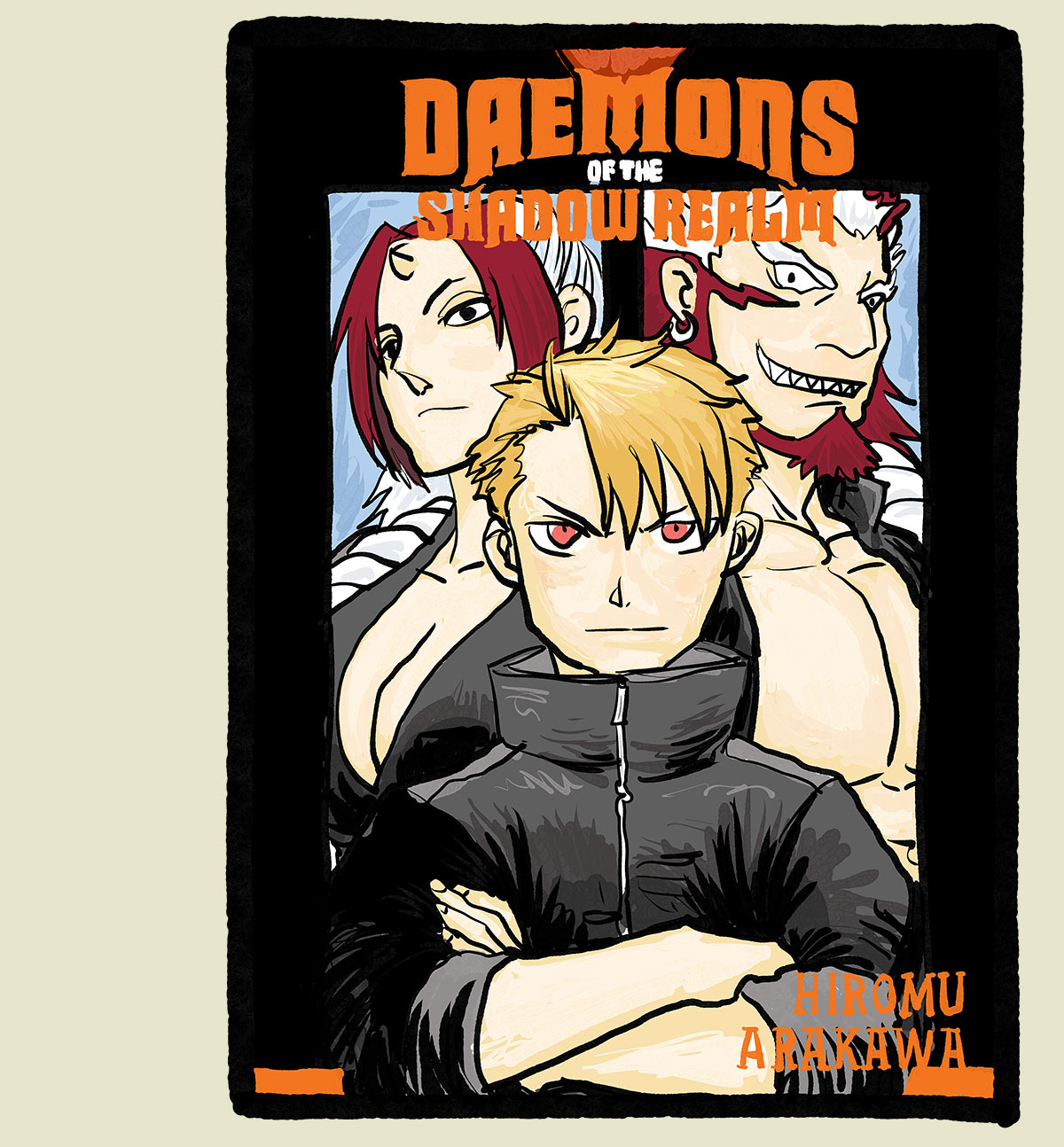

Daemons Of The Shadow Realm

by Hiromu Arakawa (translated by Amanda Haley, lettered by Phil Christie and Bianca Pistillo)

8+ vols

Published by Square Enix

ISBN: 1646091868 (Amazon)

I got this for my 15yo's birthday but read it before her so that she'd have someone to talk to about it because I'm a good dad like that. Daemons Of The Shadow Realm, despite its absolutely generic and non-memorable and kind of tryhard English title, is actually super fun.

I reread the available volumes after Christmas and was once more reminded how insane it is that Hiromu Arakawa, creator of Fullmetal Alchemist and Silver Spoon has a new series out and that it is a real banger and nobody is talking about it. The critical/marketing dereliction here is mind-boggling.

And yeah, this book rips. It's so much fun. After a couple wild switcheroos in volume 1, Daemons Of The Shadow Realm settles into a solid book of battles and mysteries about a 16yo boy trying to find out what happened to his parents, who fled his village when he was just a youngster, leaving him and his sister behind. It's funny, smart, and exciting. Basically it's what you should expect from an Arakawa fantasy adventure.

Also, a funny thing: Hiromu Arakawa is 2 months older than me. Amazing that we're exactly as accomplished as each other. Just shocking.

Princess Beast

by Sarah Burgess

Self-published

Read here

If you want reliable romance comics, you're largely going to be spending your time on Japanese productions. They've kind of got the romcom nailed down at this point. My Love Story, Horimiya, Cross Game, Princess Jellyfish, O Maidens In Your Savage Season, ad infinitum. If however you'd like to read English-language romcoms, books that are foremost written for the reader immersed in English-language culture, there are only a handful of guiding lights. Andi Watson and Chynna Clugston were big around Y2K. Bryan Lee O'Malley shone for a time. There are a new crop of good romances from contemporary creators (such as Jen Wang's Prince And The Dressmaker).

Among my favorite of the last few years is Sarah Burgess. The Princess Beast seems like an idea spun out of Moto Hagio's story "Iguana Girl." The main character is a princess named Princess. She looks to everyone like a pretty young princess, but Princess looks in the mirror and sees the truth: she is a beast. (Or it may be the other way around—there is still some mystery about Princess's beastliness.) It's about her and a sullen-but-awkward-but-kinda-cool prince. And about love and falling in love.

Burgess has a great voice for romance. She writes lively characters that can carry a banter. Her art is fantastic for the wide variety of expressions necessary to pull this kind of thing off.

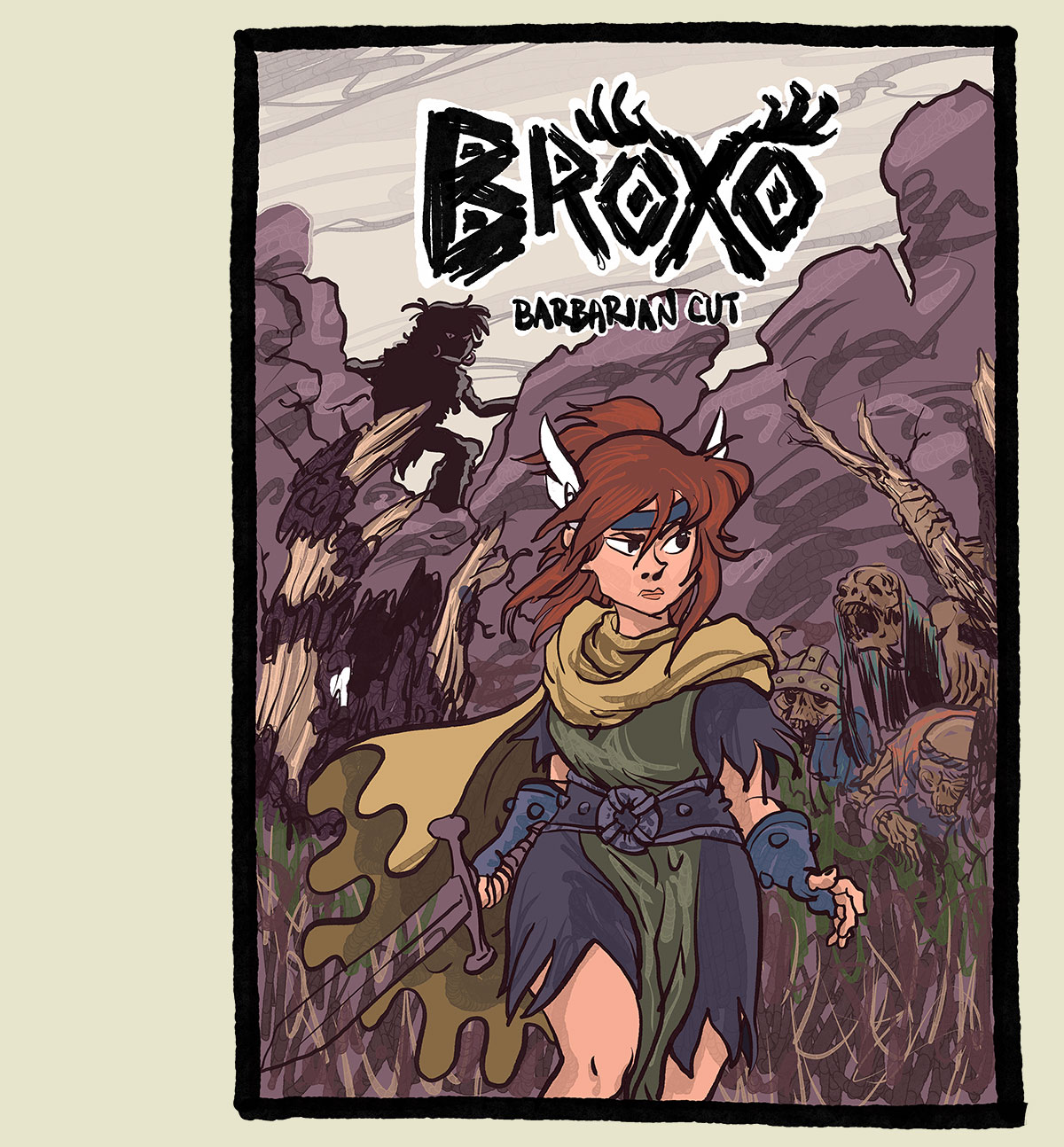

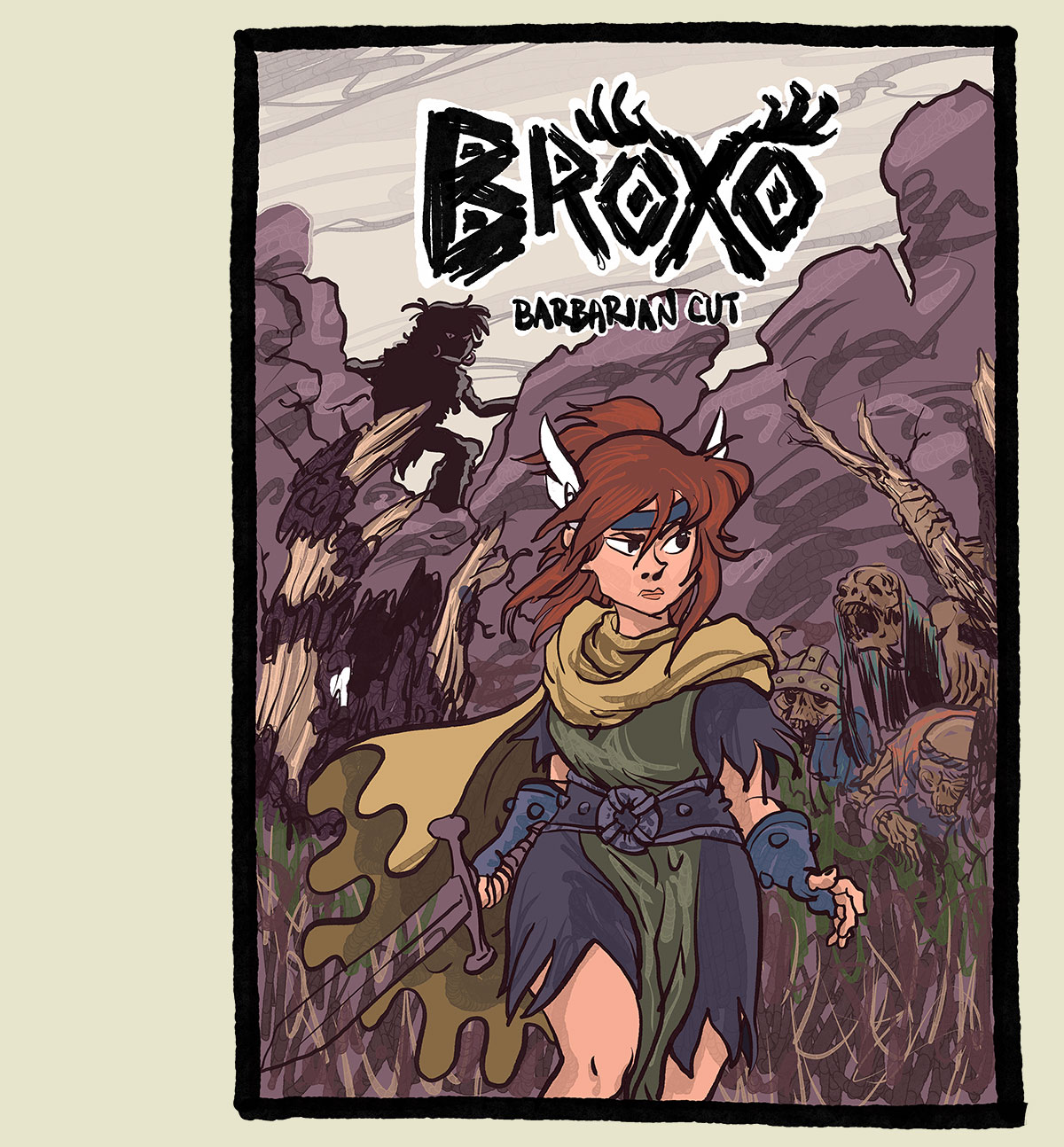

Broxo: Barbarian Cut

by Zack Giallongo (colored by Braden Lamb, lettered by John Patrick Green)

282 pages

Self-published

Download for Zack Giallongo patrons

In October 2012, Zack Giallongo's Broxo was released by First Second. Sort of. It landed well in schools and libraries, but really wasn't made available in comics shops. A missed opportunity for a book vibing off ElfQuest and the fumes of old D&D comics. At the time, six months after its release, I wrote in the middle of my review of the book:

I'll tell you this now: the fact that there isn't presently a sequel to Broxo rushing from the printers to the publisher on its way to a speedy distribution breaks my heart. Because I want more of these two. I want more adventures that will make me hurt all over vicariously (even if the characters themselves seem immune to my own current frailties). Giallongo has charmed me.

In my conclusion, I amended:

I wasn't entirely truthful in my earlier stated desire for a sequel to Broxo. The truth is I want four. At least.

Broxo wasn't, I don't think, given a fair chance to live. It's kind of like Greg Ruth's The Lost Boy in that sense. Two books that are begging for more, but weak marketing strategies ham-stringed them into an eraly grave. Giallongo, however, an avid fantasy dork, is not beyond dipping into necromancy, and so he's brought Broxo back in a digital remaster with a deleted scene and new lettering and 40 pages of supplemental material.

Partly to the end of bringing back an out-of-print book and partly to pave the way for a sequel he's hoping to release in increments through his Patreon. In any case, it's good to have one of the better fantasy graphic novels available again in this remaster. And fingers crossed for another installment!

Flash Gordon

by Dan Schkade

Published by Comics Kingdom

Read at Comics Kingdom

Schkade took over the daily serial near the end of October in 2023 and so has had nearly a year and a half at the helm. His run has been pretty blisteringly effervescent. Crisp, cartoony art with vibrant characters and fun plots with twists and twists and twists and betrayals and intrigues and shenanigans.

I couldn't imagine it ever happening, but Schkade's new run on Flash Gordon (a story whose Queen-propelled movie satisfied every Flash Gordon Need that I thought I'd ever have) has me hungry for more Flash Gordon. I don't read serial strips. I don't care about serial strips. The last time I followed serial strips (if you don't count that wild two months when I was reading Mary Worth ironically in the mid-Aughts) was back in the '80s after Empire Strikes Back released and I thought the Sunday Star Wars strips were pretty wild. And yet here I am, week after damned week, looking in on Flash and Dale and whatever trouble they're in this time. That is, I think, a recommendation and a half.

Medea

by Blandine Le Callet and Nancy Peña (colored by Sophie Dumas, Céline Badaroux, and Nancy Peña, translated by Montana Kane)

320 pages

Published by Dark Horse

ISBN: 1506742688 (Amazon)

Let's get one thing out of the way at the outset: there is no Official version of Greek myths, no canon source for the god/demigod lore. There are instead a small pile of sources, references, and (importantly) cherished additions. (For instance, the major text extrapolating the Trojan War, The Iliad, begins in the middle of the war and ends before the most famous moment of that war, Odysseus' plan with the gift horse. We get the rest from other sources.) And then, these disparate sources? they often tell oppositional versions of events. Medusa's story is substantially rewritten in Ovid to be a wronged maiden but had held little solidity even before Metamorphoses.

The point then is that adaptations from 21st century authors have a lot of freedom to pick and choose which aspects of their subject's stories to tell—and they can do so fairly. Madeline Miller does this vibrantly in Circe, picking and choosing from the Witch Of Aeaea's scattered legends in a way that emphasizes her legend in ways that are thoughtful and ring true. And here, Le Callet and Peña tackle the assorted tales of Circe's niece, Medea, the sorceress of Colchis.

Medea effortlessly draws the reader through a version of Medea's life and does so in a way that softens her choices (sometimes removing them as choices) in a manner that gets us to stay generally on her side for the duration. Honestly, any telling of any Greek myth that keeps you on the side of its protagonist is a work of diabloical acrobatics, so it's fun to see how an author accomplishes their aim. Here we get Jason and the Argonauts, the murder of Medea's brother, the murder of Medea's children, Medea attempting to poison Theseus, and everything else. This is the full story. Or at least a version of it. A well-done version of it.

On Fire

by Marnie Galloway

34 panels

Published by Mutha Magazine

Read here

"Is she also quietly on fire?" I can't be the only one incandescent with rage and terror for my kids, but I'm afraid to ask because I'm terrified that I am.

We had a shooting at my kids' school, but it was on a Sunday, a political attack targeting a Taiwanese church that met there by a unificationist. Sunday is far enough away from Monday that we didn't need to worry that our kids were among the dead, but still near enough to remind us that guns can touch us everywhere. Not that we needed the reminder. I kind of think probably every parent must live with the sense that Okay, please not today! Please let my kids come back to me today and tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow. In the couple years since, local districts have had their shares of lockdowns. It doesn't stop. And somehow this is what it means to be an American.

Galloway's On Fire is a portrait of a young mother facing the inner turmoil that comes with existing within The American Problem. It's an excellent scream into the void, or hopefully, somehow not into the void. We always hope the accumulated anguish will somehow shift something in our civic life but it's hard not to despair, hard not to rage. This is good comics.

Wild's End: Beyond The Sea

by Dan Abnett and I.N.J. Culbard

4 vols

Published by Boom

ISBN: 1608861589 (Amazon)

Several years ago, Dan Abnett and I.N.J. Culbard put out a three-volume series telling a War Of The Worlds story set in the English countryside and using funny animals as people. It was astonishingly well done, balancing attachment and expendability in a way where you never quite knew who would make it to the other side of things, but you couldn't stop getting invested anyway. And now, years later, there is another chapter to the story.

Wild's End: Beyond The Sea takes place concurrent to the original series, featuring a whole new cast, and concludes in a way that the two series could join up if there's to be a fifth book. As before, the writing is lovely and the interstitial pieces between chapters go a long ways toward giving us a picture of who these characters are. And Culbard's got a gift for drawing these animal-people. It was everything I could've wanted from a Wild's End story that didn't continue with the original cast.

Clocking In And Selling Out

by Andrew Neal

156 pages

Published by VVV

Buy here

Clocking In And Selling Out collects issues #6-12 of Andrew Neal's Meeting Comics, spooling out around 135 four-panel gag strips featuring a gaggle of (sort-of) office workers, which might trick you into thinking this was some sort of office-place satire like Dilbert or, uh, The Office. It's not. It's good. Real good. Every last one of these strips lands squarely in the range of pretty good to quite funny—which is honestly a phenomenal batting average.

Neal also somehow* landed an introduction by Peter "Heathcliff" Gallagher, which should give you a hint to its value.

*note: by "somehow" I probably mean something related to Neal's Solrad article on How To Read Heathcliff or perhaps the interview that followed, both of which I recommend to you.

Spring Tides

by Andrew White

248 pages

Published by Glacier Bay Books

Buy from Glacier Bay

Spring Tides feels like something that would have come out of Koyama Press ten years ago, or maybe Avery Hill today. Visually it resembles a more ghostly form of Connor Willumsen's Anti-Gone, but tonally it feels right in line with GG's Constantly or I'm Not Here. This is a book about living with pain, with illness, with an inability to be physically alright. It's about that from the perspective of a wife whose husband is ill and then from the perspective of a husband whose wife worries about his illness. Also, the world is flooding disastrously, so there's that too. It's good, dreamy. There are portions struck me solidly, and I think I'll definitely carry a fondness for it. In some ways, this could be Michelle and my story.

SupportProse I ReadNavel Gazing

Dogsred

by Satorou Noda (translation by John Werry, lettering by Steve Dutro)

4+ vols

Published by Viz

Read with a Shonen subscription

Dogsred is fantastic. It's a sports manga, so if you've read or watched a couple, you know the general terms of the contract, but Noda is so much better and funnier than most cartoonists doing this stuff that Dogsred really sings. I was hooting out laughs, causing my children to ask what was up. ("Nothing! Comics! Let me read!")

Storywise, it's about a genius figure-skater and Olympic hopeful who has a freakout and quits figure skating in a tantrum brought on by stress because mom recently died in an accident when she was driving him to practice and fell asleep at the wheel because she'd been over-doing it for his figure-skating career. Yeah, it's a lot.

Anyway, he and his sister (who got forced out of figure-skating bc his mom only had time/energy to support one of them) move to Hokaido (familiar to Golden Kamuy fans) to live with his grandpa, to a land where hockey is king. Pretty soon, skater lad is into ice hockey and is part of the freshman crew trying to learn the ropes of hockey with the team that has won 20 years in a row—oh, except for last year, when they lost.

What I've left out there is everything that makes the book great, which is the comic timing and most especially Noda's cartooning. His expressions are incredible. I hate reading comics digitally, but I'll come out for this. This will make a fantastic binge once it's in print. WHY ISN'T THIS IN PRINT?!

Sophie's World

by Vincent Zabus and Nicoby (adapted from Jostein Gaarder, colored by Philippe Ory, translated by Edward Gauvin)

2 vols

Published by Self Made Hero

ISBN: 1914224116 (Amazon)

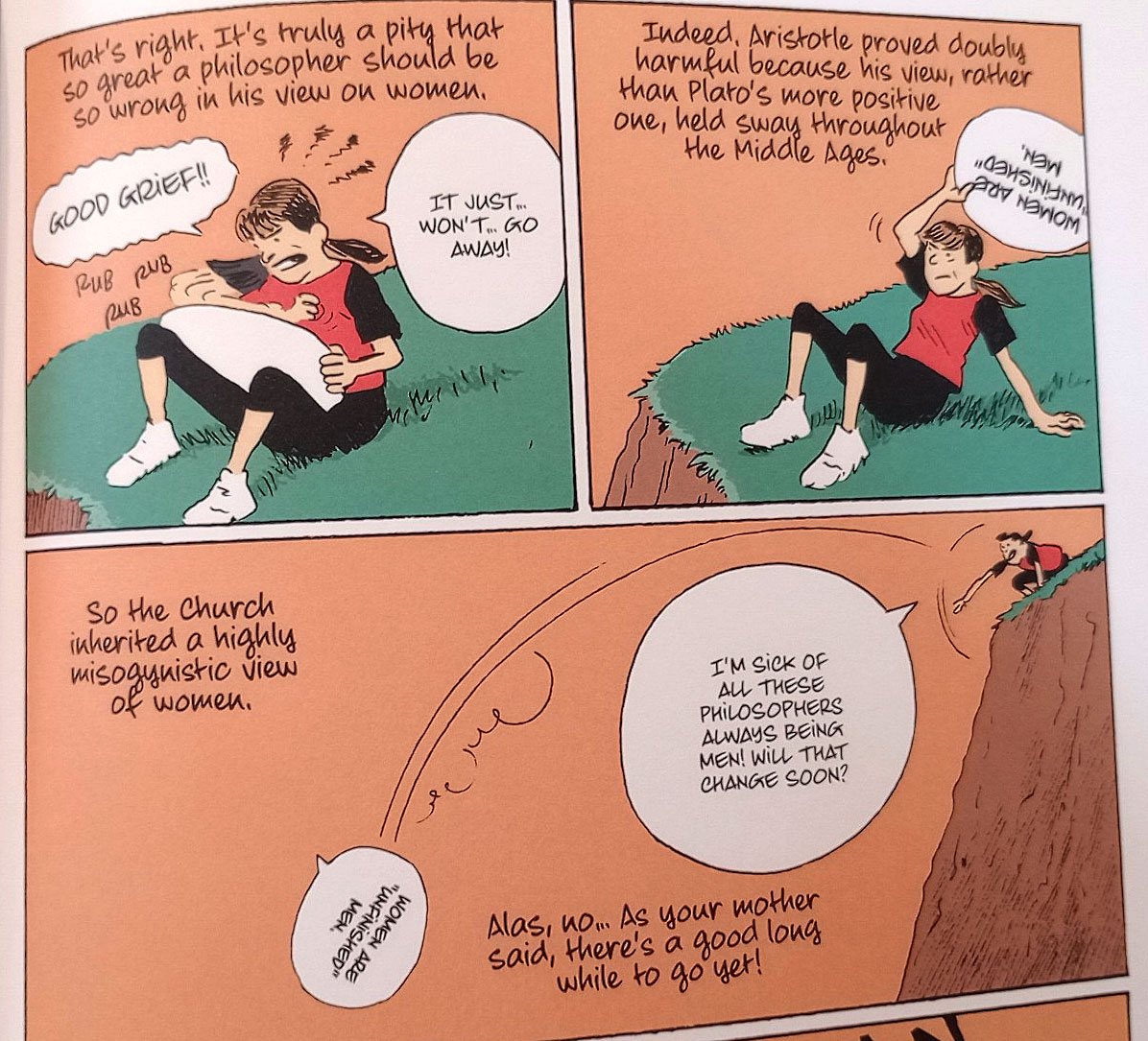

This is about as nice an introduction to the Greek philosopher's as you can get without just reading primary sources. The interior drawings are much nicer than the cover, which is a nice reversal of trend. The book does some interesting comics gimmick stuff playing with the concretization of medium forms. Here, Aristotle's words hang like a solid up in the air, allowing Sophie to demonstrably throw them out.

And the book does some cool meta comics gimmicks near the end that were rather brilliant. At one point, Opus-style, she discovers herself to be a cartoon and her recent travails merely a pedogogical device pressed onto her by her author.

Angered, she busts out of panel and stalks around the gutters. Then, using the panel border as a solid, she hangs into another character's panels, finally dropping in as large as the house she climbs down onto, having retained her size from outside the panel. Check out the four samples above to see this sequence unfold.

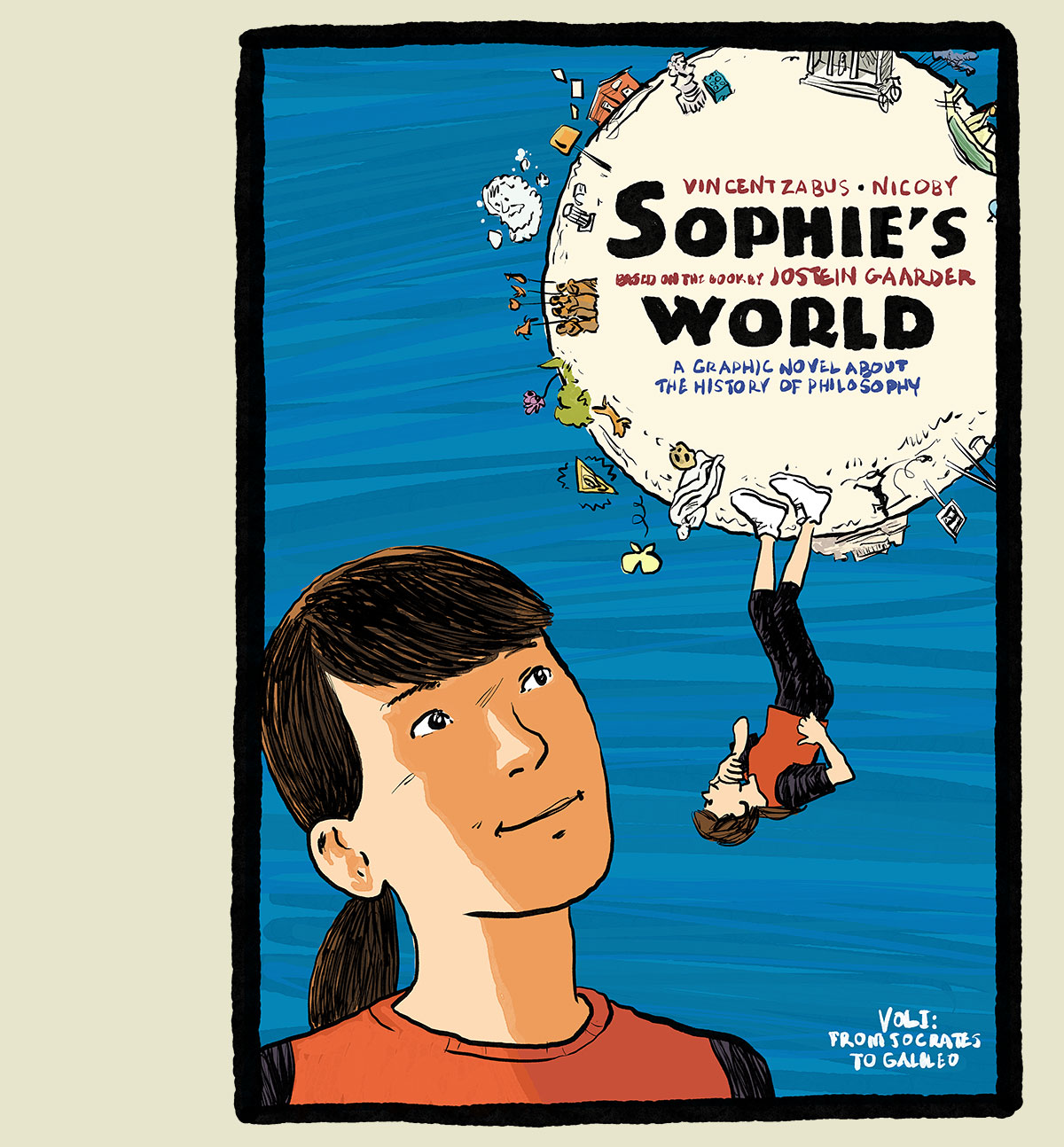

Kit + The Wolf

by John Allison

24 pages

Self-published

Read on Allison's website

I have no possible way to encounter John Allison's Kit + The Wolf with anything approaching the barest guise of objective experience. Obviously, no interaction with an artistic work can be objective—that's old had—but very often we attempt to identify our biases, acknowledge them, and tamp them down in some sort of attritional act before the gods of critique. We generally want to pretend at being even-handed, to being above our passions, to being soulless arbiters of taste. Sure, sure, it's all pageantry, but it's the accepted ritual, and we've so long made accomodations for it that we might even sometimes trick ourselves into believing ourselves Fair, believing ourselves Balanced. Because lies are comforting.

But here? With this Kit? With this Wolf? There's none of that comfort because I am so in the bag for this.

My sweet spot for Uncanny X-Men landed in the Paul Smith years. I'd been introduced to the series with John Romita Jr through issue 195's crossover with Power Pack. (I was a ride-or-die Packer.) I quickly bought up the back issue bins and trawled local cons for earlier issues, collecting all of Paul Smith and all of John Romita Jr and a little bit of Byrne, and then I started buying forward. While I preferred the Smith and Romita years, Mark Silvestri's was special because not only was Claremont deep in himself at that point, and not only was Silvestri's art screaming hot and not yet at the level of self-parody that all the future Image founders settled into, but this was the first full run of an X-Men artist that I collected month-to-month in real time and took me from seventh grade through to my sophomore year of high school. What we call the formative years.

And so here we have little Johnny Allison squirt out into the internet the pitch perfect blend of his Baddest Machinaries nuttiness with the deadest of dead-on impersonations of the Claremont/Silvestri era, and brother I am sold. There is so much nostalgia bleeding out of me over this that I doubt I'll never be able to muster excitement for a single other property I grew up with for the rest of my life. A videogame where you play Lin Min-mei and Max Sterling solving ghost mysteries on the SDF-1? Nah. Netflix going to do a prestige series of Nth Man: The Ultimate Ninja? Who cares. Studio Ghibli releasing an adaptation of the boardgame Oh What A Mountain? Bored, I am bored. I don't need any of it because I read Kit + The Wolf and that hunger for the past was rewarded and satisfied.

Akane Banashi

by Yuki Suenaga and Takamasa Moue (translated by Stephen Paul, lettered by Snir Aharon)

ZZZ

Published by VVV

ISBN: UUU (Amazon)

What a fun story. I went in as an interested skeptic but quickly swapped over to an affectionate reader and have swapped personas once again now to anticipatory fan. This is my trajectory with all the best shonen-y sports manga/anime I've ended up loving—e.g. March Comes In Like A Lion, Chihayafuru, and Run Like The Wind

It's pretty much a perfect ride through all the rhythms of a shonen sports drama with a bit of the political intrigues of Eagle: The Making Of An Asian-American President for good measure (within the rakugo world, not on the international stage).

Akane-Banashi is at its best for me when it's developed its side characters well enough and with enough sympathy that I root for them to beat Akane in competition. March Comes In Like A Lion and Chihayafuru both excel at this as well.

The major difficulty Akane-Banashi faces is the same encountered in music-forward books like Blue Giant: it's trying to portray a performance that is absolutely dependent on the heard aspect, on the auditory rhythm of the storyteller. It's the reason I've declined reading Showa Genroku Rakugo Shinju—it's just so much more fulfilling to watch the show and get to see/hear the intricacies of the performance that are impossible to get through a mere comics page. Recognizing the struggle, Akane-Banashi works hard to emphasize other interests and makes particular use of pushing the telling of stories to reflect, react to, and comment on the exterior narrative—usually to decent effect.

The book is a lot of fun, though it takes a bit to get there, and I'm pretty completely onboard for the rest of the story. Lots of drama to eat up. I'd say it struggles in its early volumes to overcome its shonen topos but once the expected vectors have been established or addressed, Akane-Banashi allows itself to flourish. I'd say this growth transition takes about four volumes to begin landing and it's maybe til vol 8 when things start to cook up nicely. It'll never become an amazing book, but it's a solid piece of entertainment and a fun way to spend a bit of your reading time.

Also, whatever the case, reading Akane-Banashi really does is make me want to watch Showa Genroku Rakugo Shinju again. Because, man, that's all-time television.

Apocalypse Taco

by Nathan Hale

144 pages

Published by Abrams Fanfare

ISBN: 1419739131 (Amazon)

Apocalypse Taco is kind of like baby's first genuine horror comic. And I mean that in a rad way. It's not like those corny, saccarhine Cthulhu For Kids books that make the cosmic horrors all cutesy and whatnot.

Nathan Hale's mostly known and enthusiatically loved for his history comics, Nathan Hale's Hazardous Tales, which are some of the best comics to come out of the last decade and a bit. While adults adore these as well (I found Treaties Trenches Mud And Blood to be the best WWI explainer I've ever encountered), the Nathan Hale books' primary audience, I'd guess are middle-graders.

So when Nathan Hale comes out with a book called Apocalypse Taco, that sounds pretty fun and right up an 11yo's alley. Which is great because the funny adventure turns into funny horror leading up to a pretty normal horror ending of "Oh, we're safe at last oh wait Oh no Oh no!!"

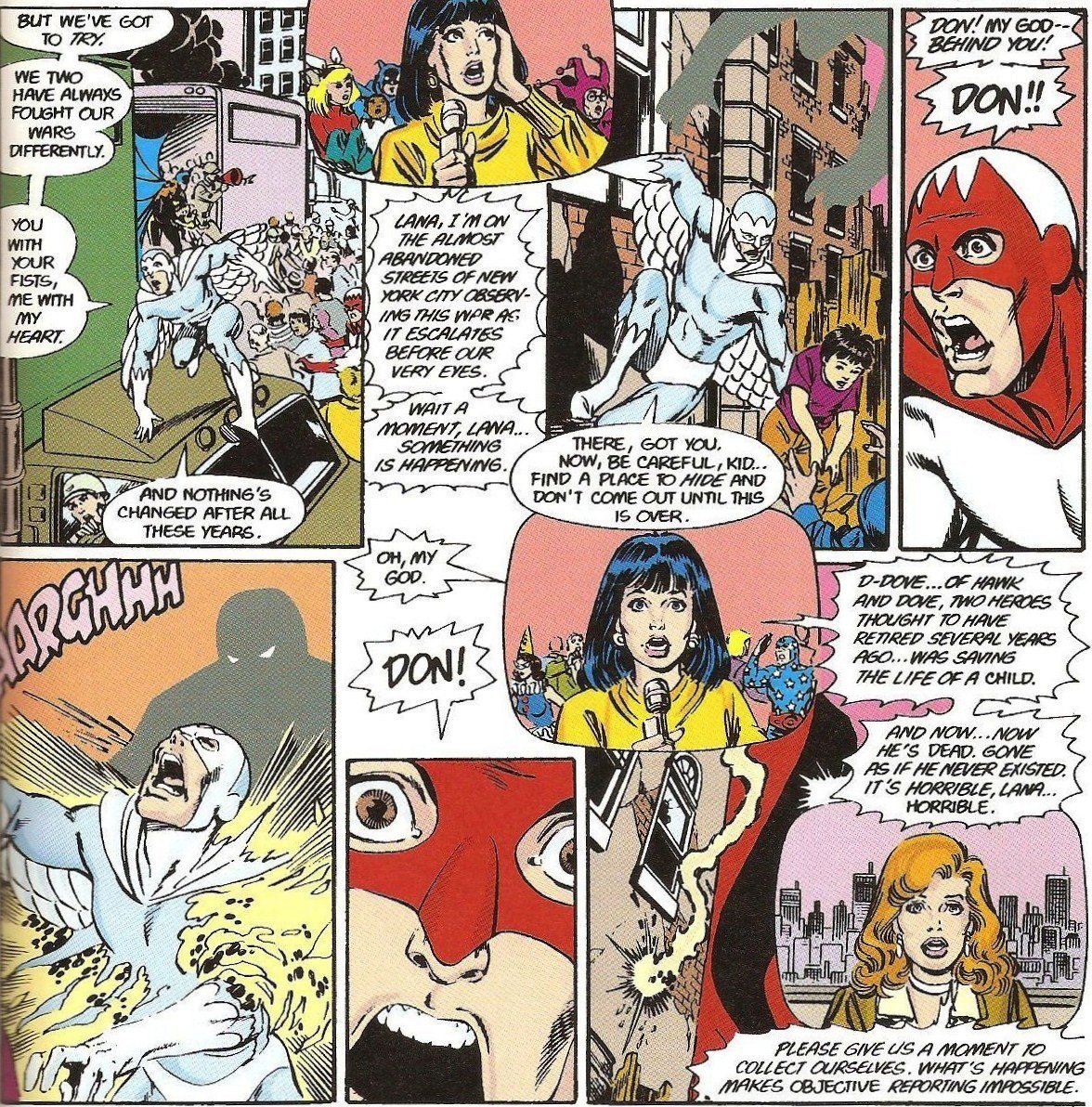

I was interested to see how my 8th grader liked it and he was excited. The horror-tastic ending jazzed him up and he felt like he wasn't being patronized. I was so glad and could relate because I remember being in junior high when Crisis On Infinite Earths came out and I watched Dove of all people get obliterated on panel from behind while helping a civilian and I finally felt I wasn't being talked down to, offered pablum and being told that everything would be alright.

The earlier deaths in the series, Supergirl and the Flash felt like marketing spectacle, but a little guy like Dove, that felt real. I'm glad taht it was a trusted source, Nathan Hale, who could give my kid his taste of that feeling.

Asadora

by Naoki Urasawa (translated by John Werry, lettered by Steve Dutro)

8+ vols

Published by Viz

ISBN: 1974717461 (Amazon)

With volume 8, Asadora gets us nine years into its 61-year storyline of a girl spending her life fighting a godzilla. It's been neat watching Urasawa draw Asa at ages 12, 17, and 21. I love watching characters age. If you're looking for a quick-paced big-moments barnburner series, you're definitely not Urasawa's target audience. In this volume about a girl fighting a godzilla, we are mostly focused on a side character's musical debut before record execs and then Asa trying to recover some film clips of a friend who got berated into doing some topless shots for a movie. Good ol' Urasawa.

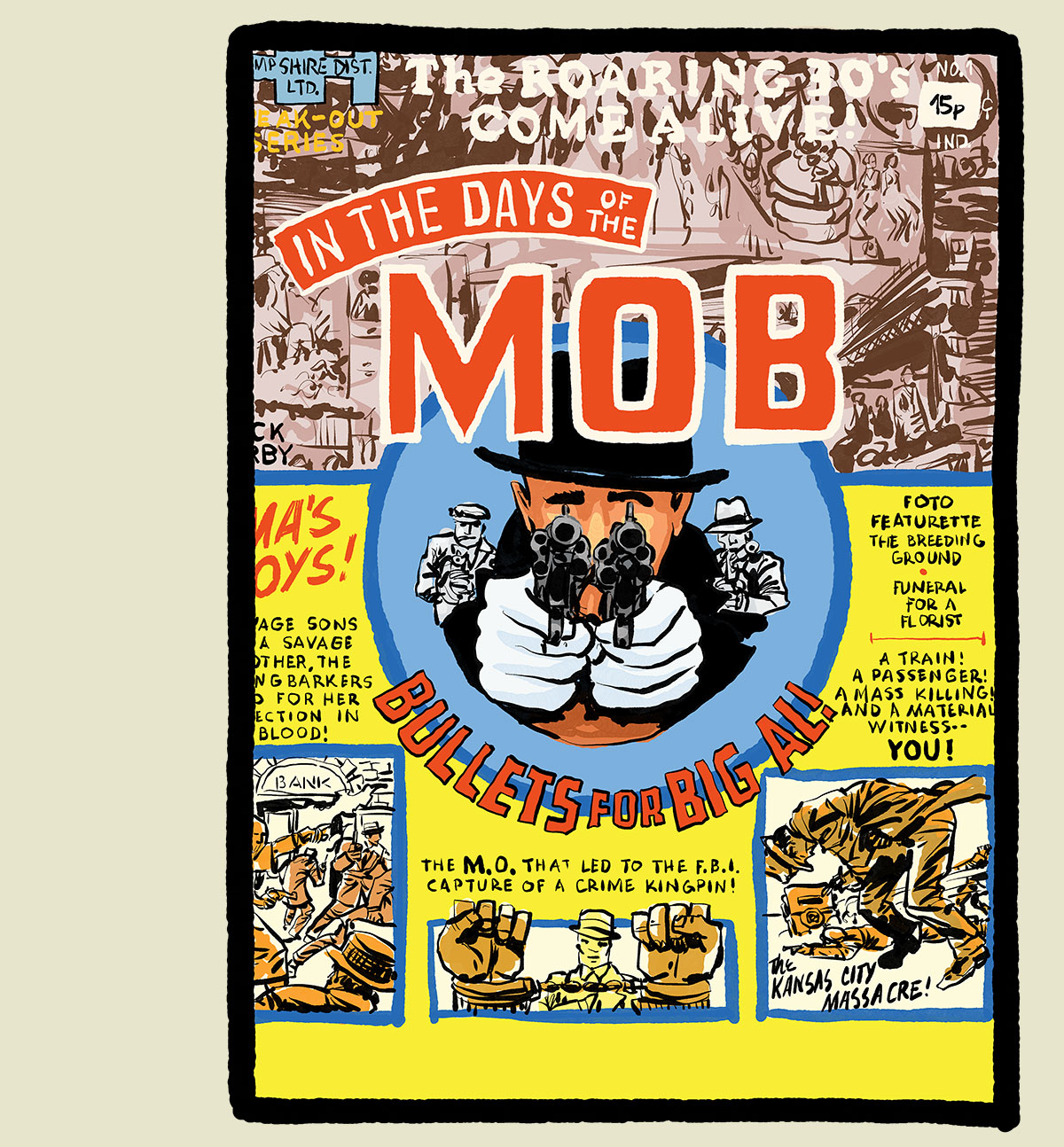

In The Days Of The Mob

by Jack Kirby and Vincent Colletta

108 pges

Published by DC Comics

ISBN: 1401240798 (Amazon)

While there was only ever one issue of In The Days Of The Mob published (and a #2 that was mostly done), it was a banger. Jack Kirby imagining hell as a panopticon where you could wander around and meet all the big name scoundrels is a hoot. In issue 1, the Warden invites the reader around to here the stories of several mobtown ne'er-do-wells and we get some fun raucous stories.

Honestly, as with most Kirby books, the real drawn is the art. The stories are fine and inoffensively crafted but they're not going to stop you in your tracks—they're not there to make you bless the fates that you're literate. They are, principally and whatever Kirby himself thought, a vehicle for delivering more of Kirby's art. These pages are a joy to look at. Rambunctuous and frisky as you'd expect. Originally black-and-white with grey washes, reproduced here in sepia. What a fun object d'art.

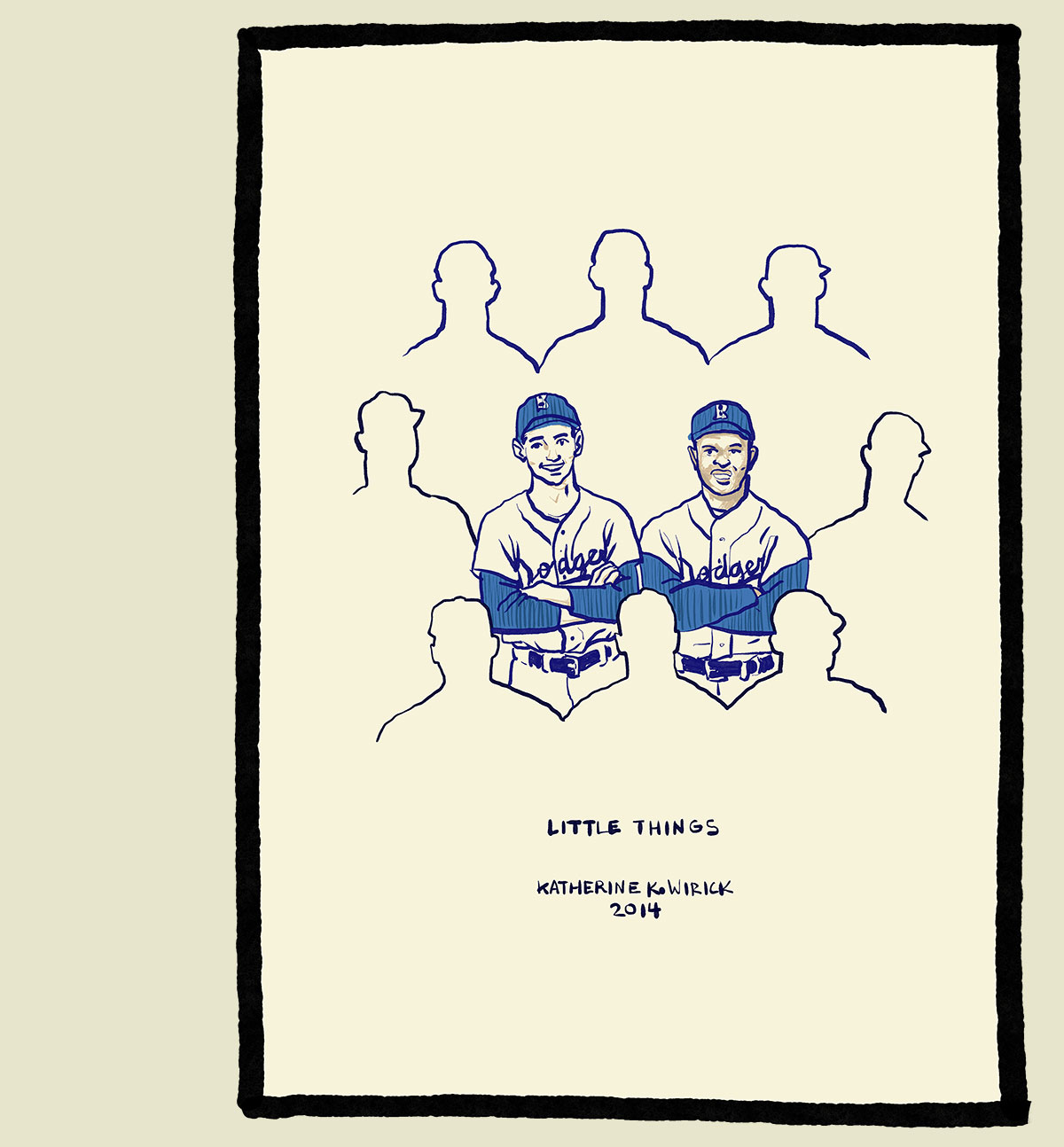

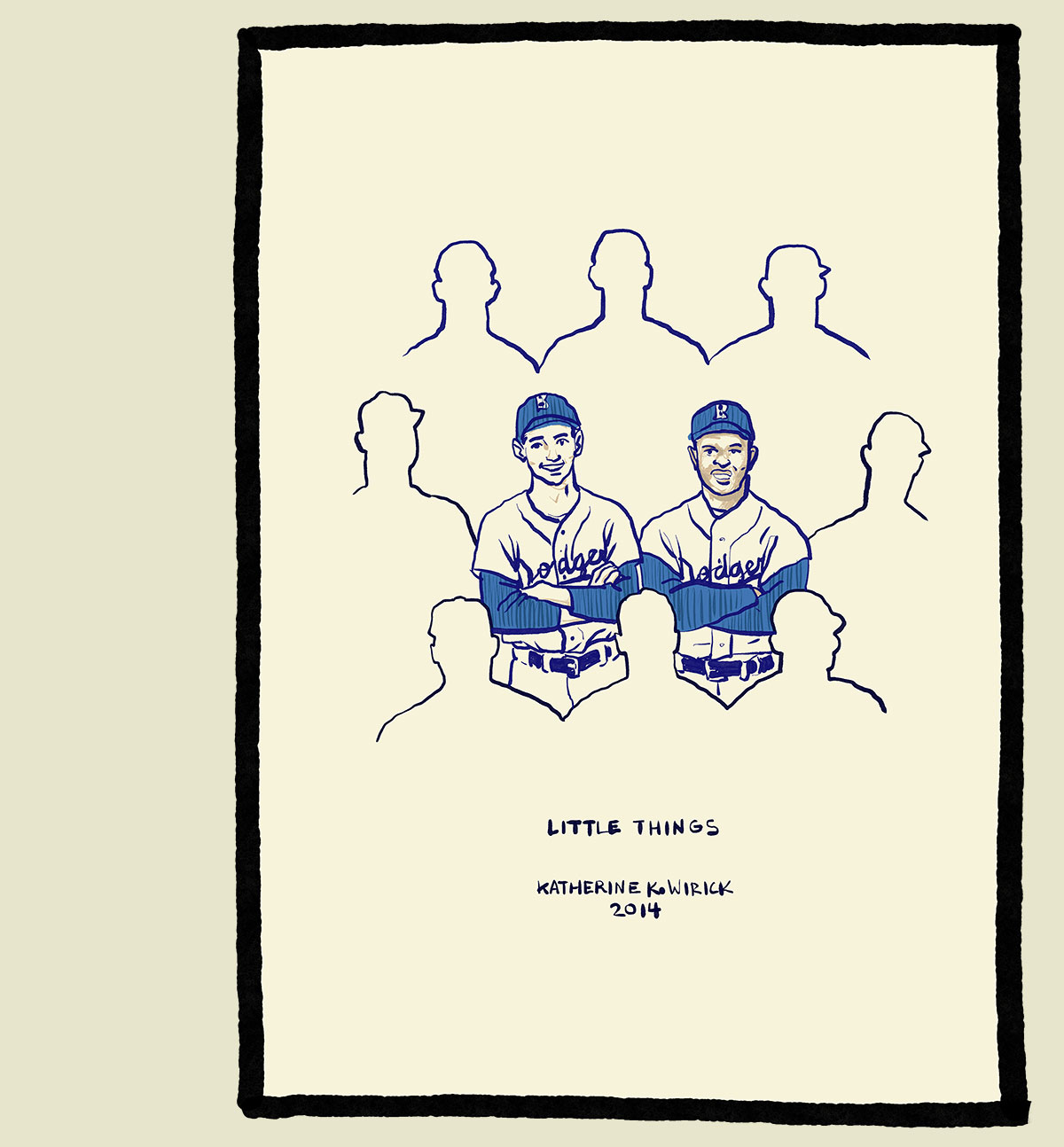

Little Things

by Katherine Wirick

6 pages

Self-published

Read here

Dedicated to her father, Wirick takes six pages to tell a poignant, small story about Sandy Koufax and Jackie Robinson. The text is taken from a Koufax interview in 2006, when Koufax is asked about anti-semetism in the league. Koufax, in humility, takes the opportunity to talk about Jackie. It's a wonderful piece, and a hopeful one. In the midst of darkness, for Koufax at least, Jackie was a light.

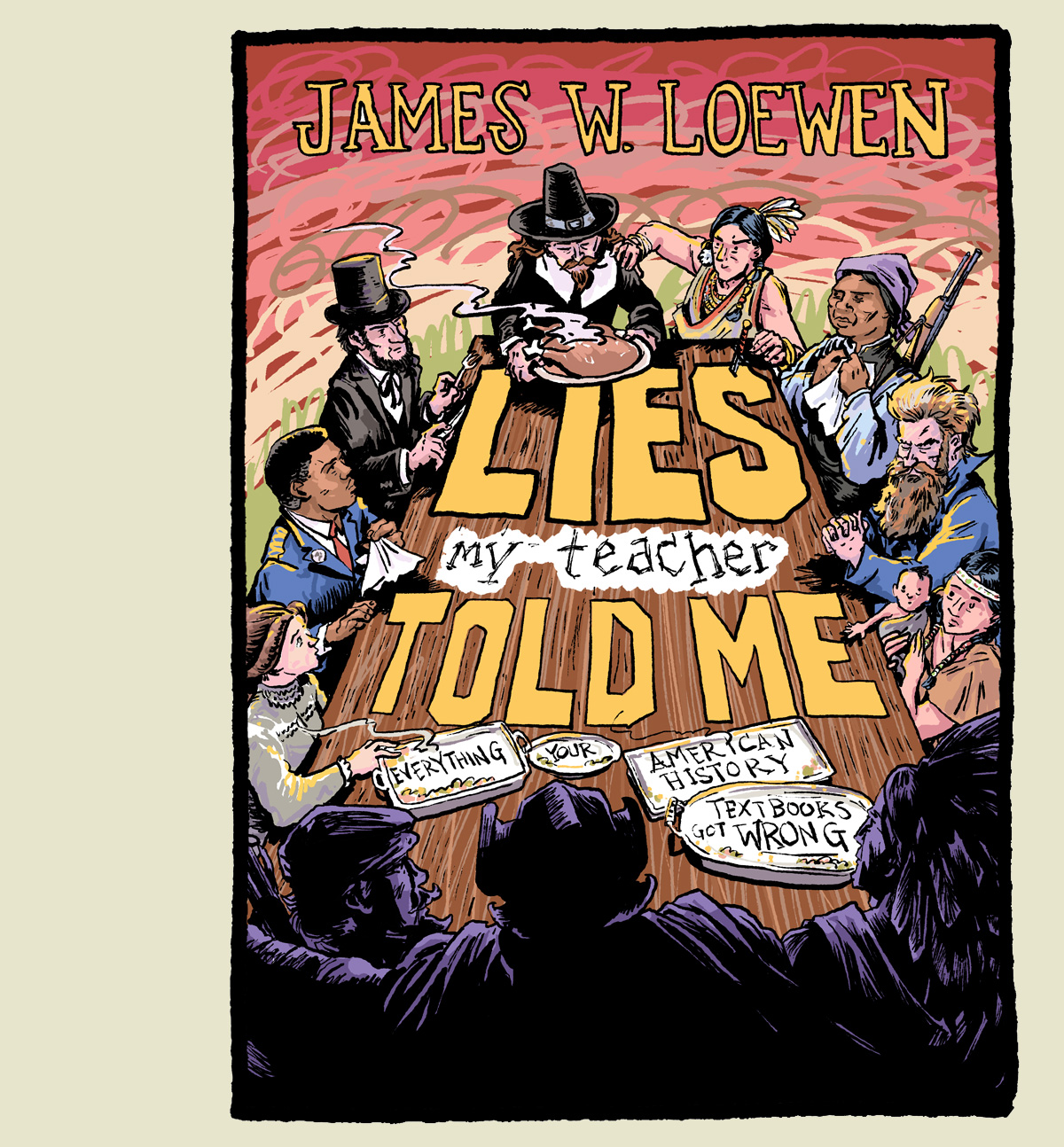

Lies My Teacher Told Me

by Nate Powell and James W. Loewen

272 pages

Published by The New Press

ISBN: 1620977036 (Amazon)

Lies My Teacher Told Me book is a fantastic resource with one substantial flaw.

Let's hit that negative first. There are no footnotes to sources. This is a book that critiques the ahistorical propagandizing of common US history textbooks and seeks to correct the stories many of us and our children grew up with. And yet, when it makes its pronouncements of how things really were, it doesn't provide readers with the tools to check their work. I'd previously read quite a few of the sources for certain details and so can verify at least those corrected facts, but that's not going to be the case for a lot of this book's readers and am I just to take the word of Loewen for the rest? (I've browsed Loewen's original from which this is adapted and he's got some endnotes, but is certainly not robust on citation.) Simply adding footnote citations would have rocketed this book up into my Top 15, easy, and it's infuriating that such a great tool for correction didn't do one of the most important things for encouraging trust in an interested, non-gullible readership.

Okay, with the complaint out of the way, let's talk about what this book gets right. For one, it's beautifully drawn (as expected) and tells its story in a well-organized way. Lies My Teacher Told Me spools out in much that same manner as Powell's other illustrated essay, Save It For Later, jusxtaposing images and prose in a way to drawn the reader through the argument being presented. One of the principal questions being asked and drilled into readers is To What End Has Our History Been Written In This Particular Way? Who benefits from This Person being lionized for These Aspects and ignored for others? What is the goal of history? Who benefits? Who benefits? Who benefits? It's driven in again and again and even without footnotes and citations and sources, it's a great question. My favorite chapter was actually the first, the one that sets up the question by focusing on the concept of historical heroes and why they're chosen and how they're sanded down and why these hollowed out facsimile's of historical people are made sacrosanct?

(Incidentally, this question applies more broadly than just to historical figures. In the midst of our current cultural moment, we see a vocal set who've made holy and sacrosanct idols of fictional figments to the point where there will be a small uproar over something as innocuous as a black little mermaid or the Lizard from Spider-Man being a woman. It's ludicrous and insane, but it's the same impulse at base, the need to make idols to form an ideological cudgel. It appears that this is somewhat instinctual to our national culture, if not to the human project as a whole.)

Let me be clear at the end here. I loved this book even though its lack of footnotes aggravated me. It wouldn't appear on this list if I didn't. Just go in knowing that it fits as a Conversation Starter rather than an argument proper. Know that it'll give you a pile of things you'll have to figure out yourself. You'll have to look up Helen Keller's activism yourself (Here's a start.) You'll have to look up whether Bartolomé de las Casas actually said what he said. (Here's a start.) You'll have to look up about Columbus, about Thanksgiving, about John Brown and Vietnam and the federal government. But Loewen and Powell give you your points to research and if they can spark your interest enough to push you to read the things they refer to, I'll consider that a win.

Dog Days

by Bianca Bagnarelli

20 pages

Published by ShortBox

I... don't know how people can acquire this.

Bagnarelli has created a wonderful story of a dog and a cat and how life spirals in unpredictible and often harrowing ways. I'm not sure if it's meant to be memoir or fiction. I do like it better as fiction because it would be inspiring to think someone could simply invent this short story. Still, even if all these things did happen to Bagnarelli and she's reporting her own experience through comics, it's done so artfully that I still love it. Her illustrations are liquid and her choice of moments to portray (and how to portray them!) are perfect. I wish this was more readily available. Maybe it is, but I just don't know where to find it.

SupportProse I ReadNavel Gazing

The Treasure Of The Black Swan

by Paco Roca and Guillermo Corral (translated by Andrea Rosenberg)

224 pages

Published by Fantagraphics

ISBN: 1683965787 (Amazon)

Man, this was a blast. I was on the edge of my seat for this true-story-novelized-and-so-fictionalized exploration of the political and legal and extralegal intrigues surrounding Odyssey Marine Exploration's subterfugenous salvage of the Spanish frigate Our Lady Of Mercy. Just a lot of quiet, explosive fun.

And as usual, Roca's artwork shines for those who appreciate his style.

Kafka

by Nishioka Kyodai (translated by David Yang)

176 pages

Published by Pushkin Press

ISBN: 1782279849 (Amazon)

I almost didn't include this since it's been so long since I read it (Feb 2024) that I don't remember it enough to talk about it very well. I kept it because even today, I find the illustrations powerful and I loved them as off-the-wall adaptations. Nishioka Kyodai adapt nine stories from Kafka with an evocative, dreamlike style. From their publisher's bio:

Nishioka Kyodai (literally "Nishioka siblings") are the brother-and-sister manga duo of Satoshi Nishioka and Chiaki Nishioka. They debuted in the weekly magazine Morning in 1989 and have since produced more than a dozen works and have become well-known for their surreal illustration style and dark psychological themes.

Ideally, next time I read it, I'll remember to come back here and add some critical thoughts.

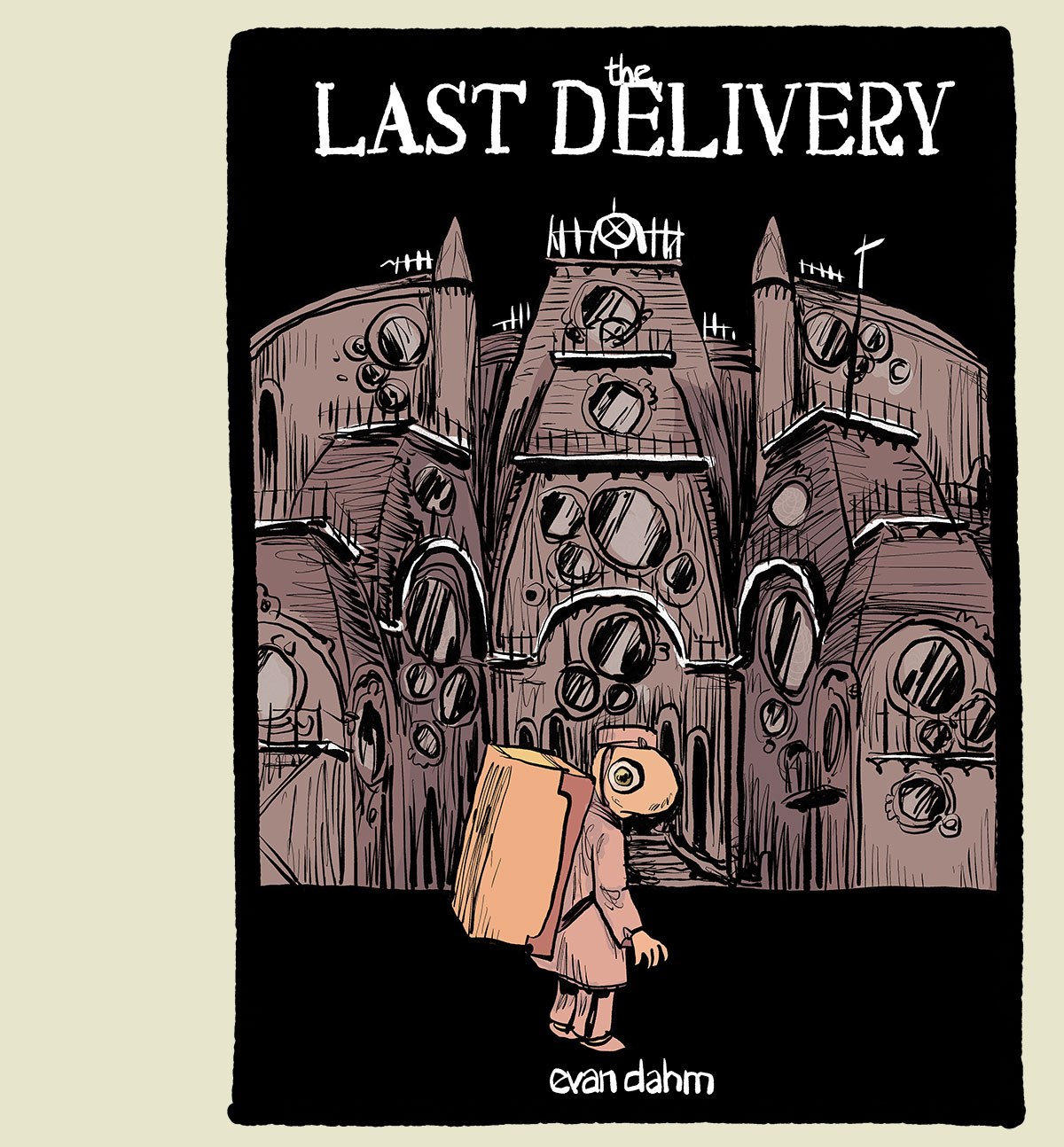

The Last Delivery

by Evan Dahm

140 pages

Published by Iron Circus

ISBN: 1638991294 (Amazon)

This is the first truly grim book by Dahm I've read, and I'm not sure what to think. I suppose that genre-wise, it's probably horror. It follows a delivery guy through a doomed party of hedonistic excess and nihilism as he has injury and abuse and horror after horror piled on to his person as he doggedly attempts to find the Resident of the house to delivery his package. This the kind of book where you read it and hope there's something going on under the hood that if you look hard enough, you just might find (mostly because we all very often spend our time hoping that behind the terror of living there's actually something meaningful behind it all). I don't know though. It could also just be as simple as an author's catharsis. Did I "get" this? No, I did not. Do I need to "get" this? No, I do not.

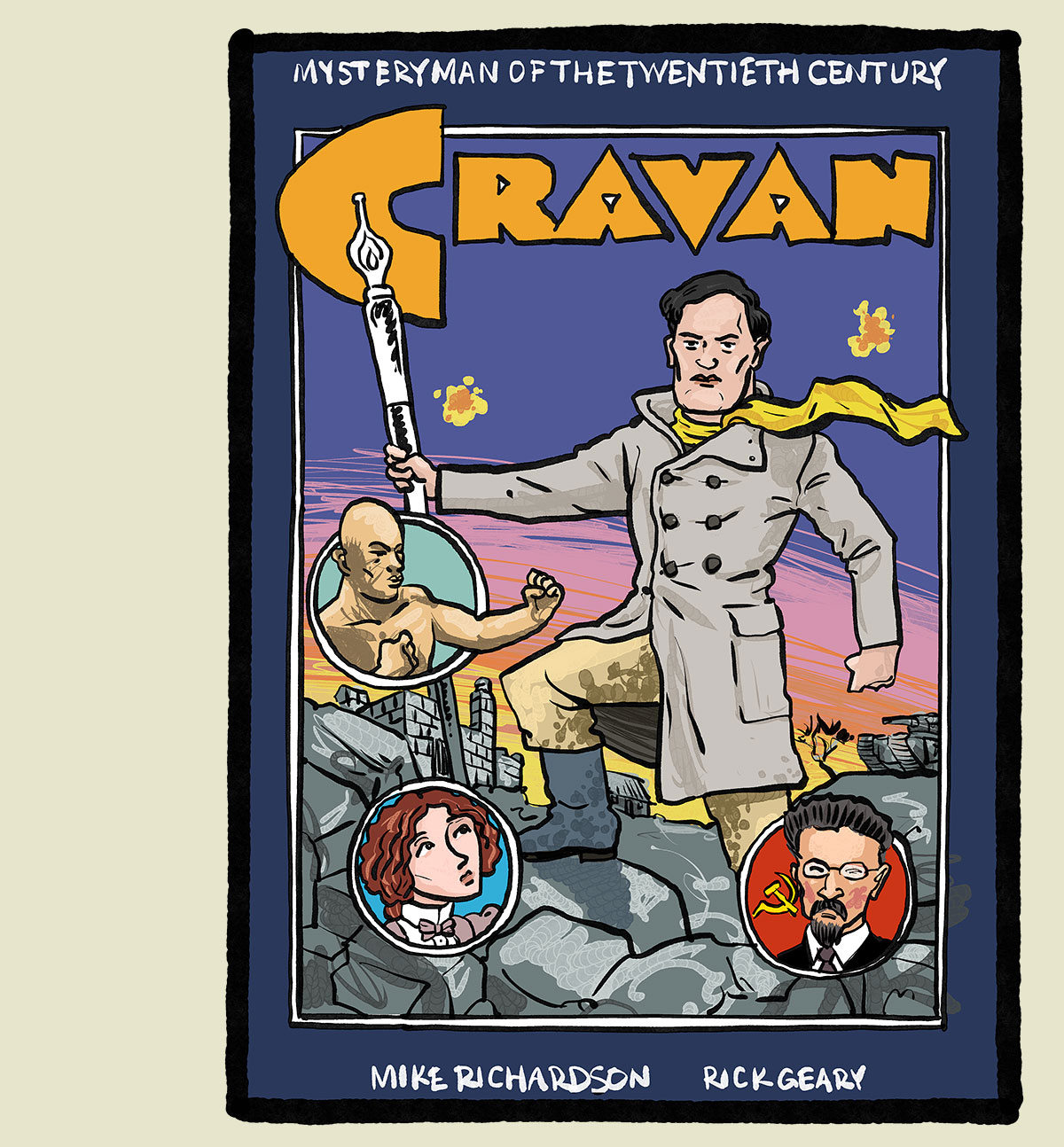

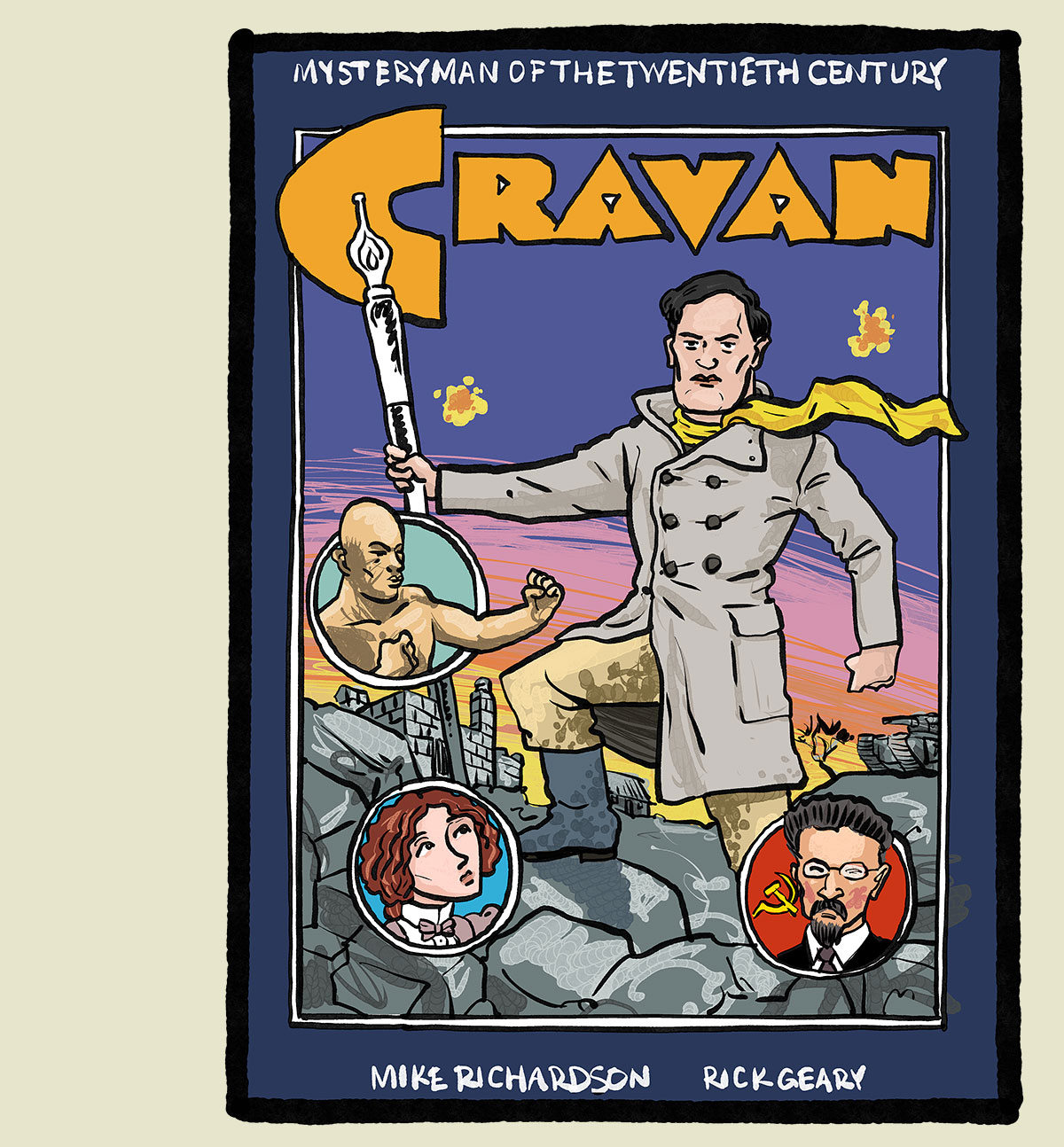

Cravan: Mystery Man of the 20th Century

by Mike Richardson and Rick Geary

72 pages

Published by Dark Horse

ISBN: 1593072910 (Amazon)

Rick Geary has made a comics career on telling the stories of famous people and events. Usually murdering people and murder events. But this time, teaming Dark Horse founder Mike Richardson, he tells the story of a non-muderer. Instead we learn of a George Plimpton type figure, Arthur Cravan. A fighter, adventurer, con-man, poet, critic, publisher, and light scoundrel, Cravan was one of many names occupied by Fabian Lloyd in his life of avoiding the people and authorities he wished to avoid. It's a fascinating story told with Geary's typical detatched and journalistic style, with art slightly resembling the illustrative work of Rick Griffin in the '60s and '70s.

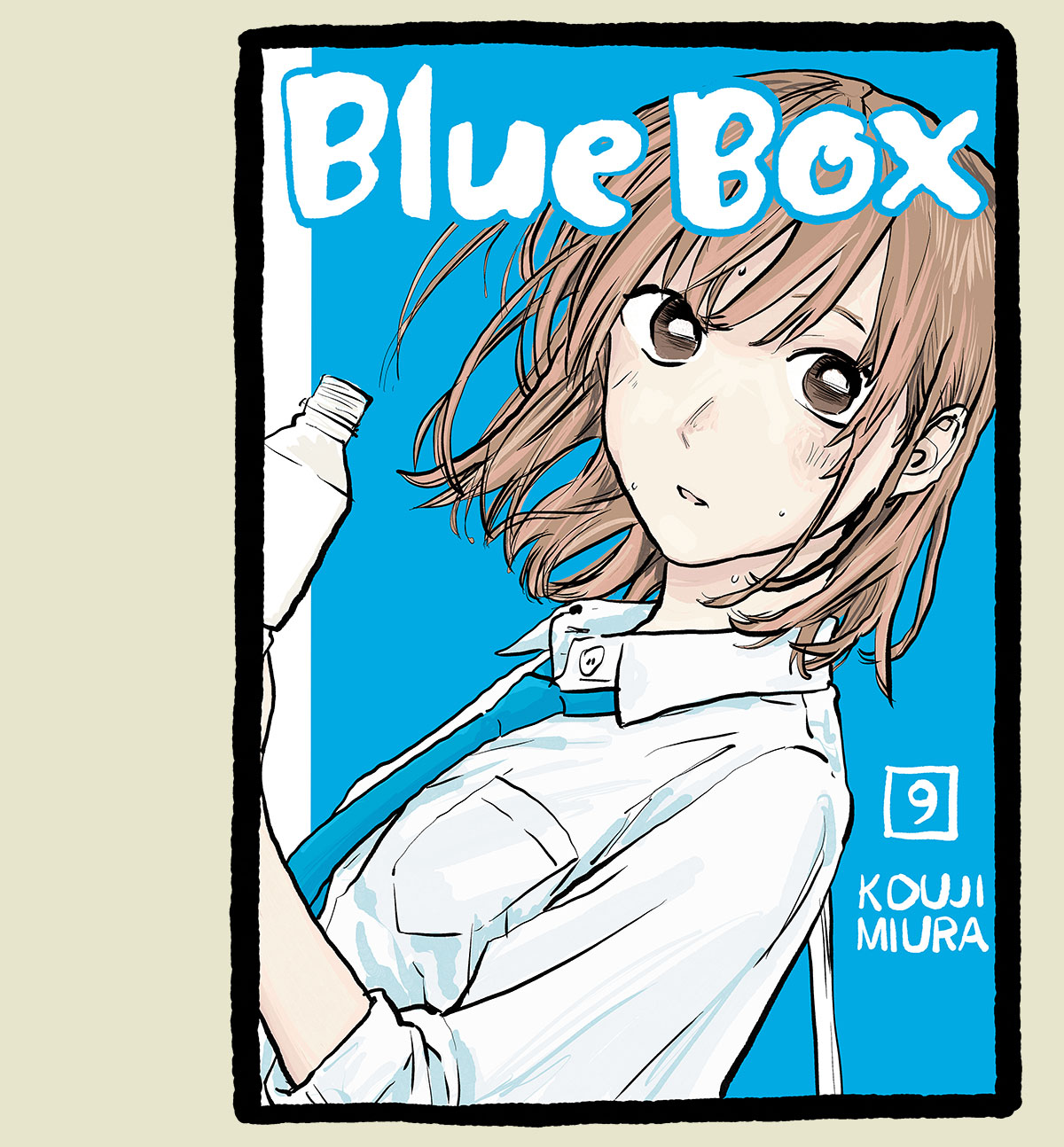

Blue Box

by Kouji Miura (translated by Christine Dashiell, lettered by Mark McMurray)

20+ vols

Published by Viz

ISBN: 1974734625 (Amazon)

I got these for my daughter for her birthday and promptly blew through them in a fun binge. It's great to find exciting romance books to sink into. Blue Box bit like crossing Horimiya with Haikyuu—only it's kind of a fake sports manga in that it's utterly unconcerned with the rules or tactics of basketball or badminton or gymnastics (the three featured sports), instead primarily using those activites as evidence of the characters' hard work and drive. It's like Horimiya or My Love Story in that it's a progressive romance where the lead couple falls in love and becomes a couple and then the story continues. It's also a bit like Horimiya where things become dramatically less interesting after the mutual confession, and the book looks to side characters' love stories for its tension (it'd probably sit about 10-15 spots higher on this list if it could've maintained the excitement of those first 12 volumes). And while it's not as comedic as Horimiya but the characters are generally more grounded, i.e. neither of the leads are weirdos.

Fighting For Tomorrow

by Asao Takamori and Tetsuya Chiba (translated by Asa Yoneda, lettered by Evan Hayden)

1+ vols

Published by Viz

ISBN: 1647293871 (Amazon)

We're getting to the point in the list where I'm guarded in my choice to include a book on the list. I liked a lot of things about Fighting For Tomorrow (popularly known for years as Tomorrow's Joe or its Japanese title Ashita no Joe). Stylistically, it's got a viscerality that I don't think we often get from mainstream works anymore while firmly attached to the cartoony vibes of the '60s/'70s scene. Fighting For Tomorrow's Joe is an interesting protagonist because he's kind of an asshole. And I'm being generous with the "kind of." He's angry at the world and everyone (and with cause!) and is cynical and burnt out and will take it all out on every last soul he meets. He makes it very hard on the people who want to show him compassion or kindness to actually want to show him compassion or kindness. He doesn't deserve to have become this person, but now that he's become this person, it's hard to see him allowing himself to trust anyone enough to allow love to exist. Everyone who shows him kindness wants something from him and he sees that and it just further embitters him. A cautionary tale perhaps, an indictment of a transactional society.

I didn't so much enjoy this, but it's good and I'll be back for volume 2.

Rare Flavours

by Ram V and Filipe Andrade

160 pages

Published by Boom

ISBN: 1608861538 (Amazon)

I'd been hesitant to pick this up. The art looks lovely, but The Many Deaths Of Laila Starr put me in an especially foul mood so I wasn't thrilled by the idea of running into that again. It can be hard to swallow the platitude that death is what gives life its meaning/makes life so sweet when you've actually seen in real life what a bastard thief death is, a robber who takes and takes and takes. The lesson of Laila Starr is stupid and hateful and it made me burn.

But (!) I kept coming back to the cover and Andrade's art, and so I gave it a shot. And it was fine. Good, even. It went down easy enough. A nice little story about how the things we make in turn make life delicious. I don't know that I especially care much about the story as such BUT it gives Andrade the chance to draw all sorts of beautiful things that we wouldn't see otherwise (can you imagine what a waste it'd be to have Andrade drawing superhero fights?), so I'm glad for this collaboration for that reason.

Tonoharu, vol 1

by Lars Martinson

128 pages

Published by Top Shelf

ISBN: 0980102367 (Amazon)

Unfortunately, I only had the opportunity to read the first volume of Tonoharu. It's good, but mostly because of how it lays out the mystery of itself to be unveiled in subsequent volumes. Structurally, it opens with a JET teacher arriving to take over from the retiring teacher. We hear mysterious things about a house of raucous foreigners. We learn that one of the Japanese teachers intriguingly holds a bit of disdain for the JET role. And we wonder how this guy's going to do, whether he'll stick with it. AND THEN, we flash back for the rest of the book to when the now-retired JET teacher we met at the beginning had first arrived to the post. And we stick with him for the duration. And presumably at least book 2 will continue with his story to bridge us back to who we thought was the main character. It's all very mysterious and I'm looking forward to seeing how things settle out.

Hearth's Haunting

by Jean Wei

20 pages

Published by ShortBox

I... don't know how people can acquire this.

Sometimes things can be just nice. Cozy. Like a man getting to know the spirit haunting his stove over a nice meal. No real stakes. No real drama. Kind of what I'd imagine the Laid-Back Camp comic would be like if I'd read it.

Shoot, I should probably read Laid-Back Camp.

Captain Momo's Secret Base

by Kenji Tsuruta (translated by Dana Lewis, lettered by Susie Lee and Betty Dong with Tom 2K)

140 pages

Published by Dark horse

ISBN: 1506740588 (Amazon)

This is a lot like My Neighbor Seki if Seki was instead a young woman and also didn't wear any clothes.

Captain Momo is about a longhaul space freighter crewed by a single person (who snuck a cat onboard with her). Her haul is a roundtrip of 3 years and she's abused the food replicator, reprogramming it to produce really anything she can think of. She's got limited battery power for her trip and her excessive use of the replicator to make boks and books and books (and sometimes toys) has her using more energy than the ship has alotted to the task of keeping her alive so she's disabled everything she can think of to save power while she continues to abuse the replicator. Out of boredom. Out of addiction. Either way. It's a funny set up and every chapter is a short slice-of-life bit feature What Has Captain Momo Replicated Now?

There's another funny bit (not haha funny, more like 😒), but it's more meta, and that's how Tsuruta just seems to really really really love drawing fit young women. Emanon? Check. Wandering Island? Check. Captain Momo? Here we go again. Only this time he's figured out a reason for her to be nude for the entire book (basically), giving himself and others a loincloth's worth of cover for the excuse, Well, it makes sense that she's naked! And yes, it does roughly make sense that a human completely alone for months would forgo clothing if the atmosphere were amenable (before I got married, I rarely wore clothes at home when I lived by myself), but borrowing from the trailer to Parenthope, which keeps playing on my Instagram feed:

OLD MAN: Parenthope, would you marry me if I were 40 years younger?

PARENTHOPE: The real question is would you marry me if I were 40 years older?

We know the answer and it's the same for whether Tsuruta would do the same book if Momo were a 57 year-old—or if Momo were me. (Of course he wouldn't, don't be ridiculous.)