Welcome to my annual attempt to share what I feel are the best comics of the previous year (in this case, the books of 2017). Before we get to the goods of it all, a few shoutouts.

- First to the comics shop that got me started on this path, Comic Quest in Lake Forest, California. You were Little Billy's Funny Book Store for about a year after I found you and then evolved into Comic Quest. You faithfully got issues of Power Pack into my hands in elementary school, X-Men in junior high, Akira in high school, and when I was ready to move away from capes into the late-'90s and Aughts indie scene, you kept me stocked up there too. I went from a dippy little kid to an awkward teen wearing a Diving Tony The Tiger for a necklace to a vaguely responsible adult. Thanks for the times Don et al.

- Next, Paul Lai of The Comics Syllabus. You're a good and valuable critical voice and have been a good friend. Dig deep, man!

- Last, three books from a few years back that would have pretty easily made my top 5 this year had they been released this year: 1) Come Prima by Alfred (available only on Comixology ridiculously enough), 2) Ordinary Victories by Manu Larcenet, and 3) Aya by Marguerite Abouet and Clément Oubrerie. All three are magnificent examples of the form, delightful expressions of the human experience, and you should seek them out should you find yourself looking for something to read.

Oh! and one other thing. Here's a 31-page minicomic I did fo Inktober this year, if that's your thing. It's very lightly not safe for little eyes, so...

Okay then, of course all the usual obnoxious caveats apply: a) that these lists are always only going to be a highly subjective record of tastes of a particular moment in a given segment of time; b) that it's virtually impossible and actually impossible to retain the same memory of a work read in January as it is of one read in November; c) that I of course haven't read a great many of the potentially fantastic works from across the year. All that's the same-ol' same-ol'.

Eligible for this list I'll be including:

- Comics printed in collected form for the first time in 2017

- Comics printed as books for the first time in 2017

- Comics printed as books for the first time in the US in 2017

- Comics published on the web in 2017

- Comics published through digital subscription services like Crunchyroll in 2017

- Important comics reissued for the first time in many years

(Example: I don't read comics as individual issues. Even though the entire Prophet series ended in 2016, it didn't end until 2017 for me because I only read print comics series in collected form. So when I list Prophet, which concluded for me in January of 2017 but seems super far away to you, now you know why I listed it.)

I believe that covers all my bases. Really though, I'm less interested in being a stickler for details than I am in just flat out recommending you some great comics reading from over the last year. So let's do that.

1–1011–2021–3031–4041–50

51–6061–7071–8081–9091–100

MetricsExclusions 1Navel Gazing

My Best 100 Comics of 2017

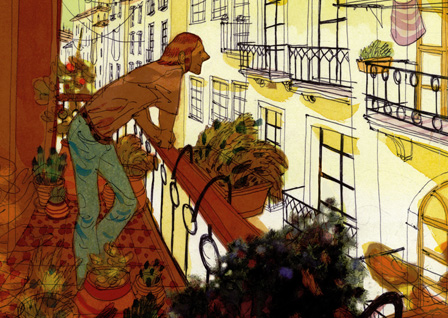

Portugal

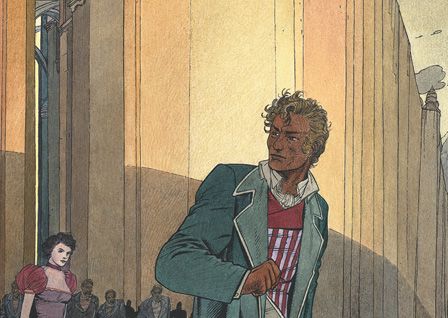

by Cyril Pedrosa

264 pages

Published by NBM

ISBN: 1681121476 (Amazon)

Genre notes: day-in-life, Portugal, France

I may be something in the bag for Cyril Pedrosa. When I codified this list, I was going about my merry business gathering assets for each entry and it struck me. Pedrosa's Equinoxes was my №1 book of the year last year. And now, again I let him sweep me off my feet. I second guessed myself for a split second but flipping through Portugal again calmed my hesitations. This book truly is a marvel. It's beautiful, thoughtful, lively, and lived in. It's sentimental without ever feeling cloying. It offers real human dilemma without ever feeling overbearing. Quite simply: it was a joy for me to inhabit.

Artistically, it somewhat resembles Equinoxes mostly in the colourful changes from page to page, but where in Equinoxes those shifts corresponded to seasonal drift, here they are provoked by mood and location. Portugal is an easier book to fall into. It requires less of its reader than Equinoxes—there is less burden on the reader to discover for themself why Pedrosa is depicting a thing in a particular manner. Which, depending on your disposition, may not be a bad thing.

Pedrosa, over the years, has crafted three of my favourite graphic novels of all time. Three Shadows. Equinoxes. And now Portugal

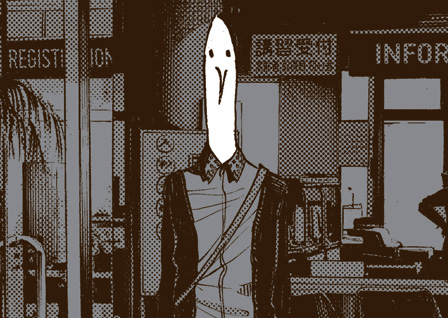

The Girl From The Other Side: Siúil, A Rún

by Nagabe

4+ vols

Published by Seven Seas

ISBN: 1626924678 (Amazon)

Genre notes: fable-esque, faery tale-esque, horny guys, er... guys with horns

This series is straight magic. It's beautiful, spare, touching, and imaginative. It doesn't overplay its hand, and it's a haunting delight.

Basically, there's this little girl who was left behind outside the city walls where the cursed outsiders dwell. Being touched by an outsider means that you too will be cursed and will turn black and grow horns like they do. Only, this little girl lives in a small cottage with one of the outsiders who is bent on protecting her and teaching her. He looks like a monster but he worries about telling her the truth about how she was left behind by the Auntie whose return she eagerly awaits.

Pope Hats

by Ethan Rilly

5 vols

Published by AdHouse

ISBN: 1935233408 (Amazon)

Genre notes: day-in-life, law firms

It took me forever to get on the Pope Hats train. I was even at the Small Press Expo the year it won an Ignatz, but left without purchasing. A big part of my reluctance is that I don't really have a viable means of storing saddle-stitched work. I have shelves that are good for stuff with spines where you can read a book's title, but nowhere to keep zines or periodical issues. But like, who cares, really, right? What's important is that I did end up getting all five issues of Pope Hats, which means the book has to make it on this list fairly high - because I'd be negligent not to include it very high.

Pope Hats is very good at what it does. It tells the story, principally, of Frances Scarland, who begins the series at the low rung of the law firm totem pole but gradually begins to climb, almost accidentally, through no ambition of her own. It's the story of her and her best friend Vickie (an actress) and the friends like Peter who enter their orbit. It's the story of pretty real feeling people living pretty real feeling lives. It's comfortable and enjoyable and relatable and pretty much perfect. I'm glad I'm on this train now. Choo choo.

Eartha

by Cathy Malkasian

256 pages

Published by Fantagraphics

ISBN: 1606999915 (Amazon)

Genre notes: fable

Eartha is prodigiously imaginative and for something that has a moral in the same kind of way that the Gigantic Beard That Was Evil does, it never feels overly didactic or preachy. The illustrations are pretty too.

Eartha is a woman, guileless and strong and fat. She is everybody's favourite citizen of Echo Fjord, reliable and buoyant. Echo Fjord is an agrarian place where the dreams of the City come to visit (literally). The unfulfilled longings of the citizens of the City have for thousands of years migrated to the Fjord for catharsis and release. Only now, after a thousand years, few dreams arrive, and Eartha worries that everyone in the City has died from a war. Things happen and she goes to the city and more things happen and it's all pretty wonderful and the contrivances of the plot are pretty unebelievable but none of that matters because everything is pretty much just magic.

Lovely book. A bit large and unwieldy though. (12 in wide, 10 in tall, an inch thick and hardcover.)

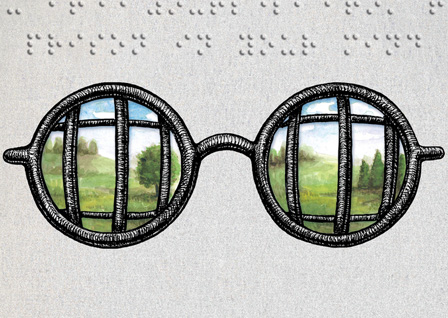

The Hunting Accident

by David Carlson and Landis Blair

464 pages

Published by First Second

ISBN: 1626726760 (Amazon)

Genre notes: biography, history, true crime, literature

Not only is The Hunting Accident a gripping exploration of a very real intersection between an unfortunate, haunted young man and a famed criminal, but The Hunting Accident is also (and perhaps primarily) about fathers and sons and that turmoil that builds when hidden pasts are not encountered in an environment built on trust.

The Hunting Accident in the main spans around four decades, moving us from around 1930 to 1970. Some episodes occur earlier, and the epilogue travels all the way to the present day. Matt Rizzo has a problem with his son. In 1959, Rizzo’s son arrives from California where his mother has just expired. Rizzo is blind and an unsuccessful writer, but he tries to do well by his son. He explains his blindness as the result of a hunting mishap when he was a child. There’s more to it—much more—but Rizzo feels compelled to hide the truth of it from his son as much in order to protect the young boy as to protect his own heart.

Eventually, it comes out that Rizzo spent time in prison as a young man, cellmate to Nathan Leopold Jr (of the famous Leopold and Loeb). From there begins a raucous, wonderful exploration of mid-twentieth-century history, prison life in the same era, great literature, and the struggles that sons have with their fathers. The story is dripping with fathers and sons—and while all of those relationships resemble not even remotely my own relationship with my father, there’s still a little something that sounds familiar. The world is recognizable.

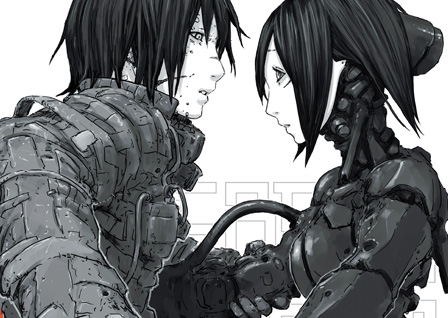

Blame

by Tsutomu Nihei

6 vols

Published by Vertical

ISBN: 1942993773 (Amazon)

Genre notes: speculative fiction, action, grotesque, whoa

Many of you may be aware of Tsutomu's work through Netflix's release of the anime adaptation of Knights Of Sidonia. KOS was his most recent series and it's polished and streamlined and tame. Still has some mind-expanding spec-fi going on in it, but it's tame nonetheless.

KOS is his third major series. Biomega is nutty and insane and rad and is his second series. Blame! is where he started off and it makes everything that follows feel a bit shabby. The art isn't as professional and tidy as Knights Of Sidonia, but this book has gumption.

Vertical just rereleased the series in what's called the Master Edition. Probably to coincide with the animated series adaptation that Netflix is picking up (May 20 - https://youtu.be/hwy806RC2-Q). The Master Edition is gorgeous. 7.25 inches wide and 10.25 tall and an inch-and-a-quarter thick. These are big luxuriant paperbacks and really show off the unvarnished dynamism of Tsutomu's vision.

The story is about this guy, Kyrii. He's a bit quicker and stronger and more immortal than normal. He gets beat up a lot and he beats up a lot. He is scaling through the strata of this behemoth complex called the City to locate someone who still has the net terminal gene. This is far far in the future. Humanity has evolved down a variety of lines and there's been the introduction of some kind of mutagenetic infection. And when I say the City is large, I mean that it's grown enough to encompass Jupiter. Much larger than your average Dyson sphere. Life is cheap and rough and synthetics and ancient programs hunt down humans, so you can't really get too attached with many of the people Kyrii meets on his travels. It's rare they'll last long.

Canopy

by Karine Bernadou

80 pages

Published by Retrofit

ISBN: 1940398606 (Amazon)

Genre notes: fable, social issues, a bird with both boobs and a wiener

Canopy is pretty rough in the sense that it describes a female experience (not *the* female experience but a common female experience) in stark though oblique terms. One friend who read it was so bowled over that she sobbed in public while reading it. I was not quite as overtly affected but I did want to hold my daughter tight for hours and days and months after, keeping her safe from the potential terrors of life in a world overpopulated by men who would consciously or unconsciously wound her with their needs, desires, and way of being.

Canopy demands an interpretive frame of mind. It's less straight narrative and more parable. It's a series of connected experiences where figures represent experiences or types of men. For the casual reader, understanding may be obfusticated. But as one dwells on the images, they begin to coalesce and one begins to grasp at potential reasons Bernadou may have chosen to depict things in one way rather than another. And like with all parables, they who have ears to hear, let them hear.

The book opens with the infant woman nursing at her mother's breast. Her father sits at their side. Over the course of a couple pages, the infant woman grows to maturity, still nursing as her mother grows older, hair turning to white. The father is present for a couple panels and then only in the family portrait on the wall behind the mother, then absent. When the once-infant woman reaches adulthood, her mother's breasts dry up and she can no longer nurse. Her mother blind folds the woman and leads her out into the magical dangerous forest and leaves her. A man approaches (he is nude, we do not see his face) and leads her further into the forest. By her thoughts, we see she believes this man to be or associates this man with her mother. That's about the first five pages and introduces the idea.

Sound Of The World By Heart

by Giacomo Bevilacqua

192 pages

Published by Magnetic

ISBN: 1941302386 (Amazon)

Genre notes: New York living, photography, magical realism

Sam's a photographer for a boutique-published magazine in France. He's in New York recovering from a broken heart and using the opportunity to work on a special project for his editor. He will spend two months without communicating to another human (apart from morning updates to his editor via texting) in the midst of the bustling throng of the metropolis. He can eat at a particular restaurant or his apartment no more than three times in that two month period, forcing him to find ways to interact without speech. A key prop in his operating mode are huge headphones with which he can appear logistically insensible to dialogue.

This book is gorgeous, the illustrations lush and colourful. This is one of my favourite reads from 2017 so far. I can see it fitting in my end-of-year top 10 pretty easily. It's about the romance of living, the romance of a challenge, and the romance of a city. Your experience of the book will definitely be helped if you can give yourself over to the idea that New York City is a living, breathing entity suffused with a kind of special magic. I've been there once and my personal experience said the opposite, but suspending my bias for the space of this book turned it into something wonderful.

Generations

by Flavia Biondi

144 pages

Published by Lion Forge

ISBN: 1941302505 (Amazon)

Genre notes: day-in-life

"I thanked all my mistakes and my cowardly choices. If it hadn't been for them, I wouldn't understand."

Generations is about second chances. Generations is about growing up. Generations is about other peoples shoes. Genreations is about family and what family means and what family does and how family will make you the strongest person in the world if you let it—and sometimes maybe if you don't.

Genreations is about Teo, who ran away to Milan in the face of his father's unhappiness when Teo comes out to him. Generations is about Teo, who comes back home to the country, living with his grandmother and three aunts and his pregnant cousin while he tries to figure out whether to and how to patch things up with his father. Generations is about Teo, who is trying to not be a great big baby about life for the first time in his life, only he needs help but isn't that good at asking for help.

When I first was reading Generations, I thought it was fine. A good book but not a great book. It hit a lot of notes I'd seen before. But then, somehow in the final twenty pages or so, in the book's closing sort of an essay, I was swept up into this roiling torrent of emotion. I found myself deeply and satisfyingly moved. It's not a feeling that hits me often enough while reading and for that I'm rewarding Generations as best I know how. This book will remain a treasure to me.

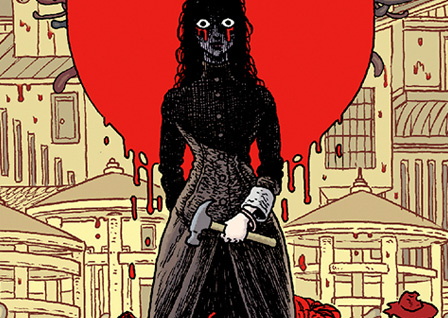

House Of Penance

by Peter J Tomasi and Ian Bertram

176 pages

Published by Dark horse

ISBN: 1506700330 (Amazon)

Genre notes: hallucinatory biography, pretty gore

Man. This thing was an incredible experience, mostly from the art but the writing made room for the art and that's respectable. It's gorgeous and grotesque.

It's basically hyperrealized biography of Sarah Winchester (of California's famous Winchester Mystery House). The barebones of the history is that Sarah Winchester married into one half of the Winchester Repeating Arms ownership. Her husband and 5yo daughter died and she kind of went a little haywire with depression, moved out to San Jose, California and started work on a house (possibly to comfort the spirits of a) her husband and daughter and b) the spirits of those slain using Winchester guns. She spent basically $23K a day building, tearing down, and rebuilding the great house (at its height, possibly 7 stories, but after the SF quake only 4). There are doors and staircases that lead nowhere.

Tomasi and Bertram embellish the legend and make her truly bonkers but also sympathetic. The book is deliriously full of hallucination and visual metaphor. It was a wild ride.

Strangely, though, they got the year and age of her death really wrong.

1–1011–2021–3031–4041–50

51–6061–7071–8081–9091–100

MetricsExclusions 1Navel Gazing

Ooku

by Fumi Yoshinaga

13+ vols

Published by Viz

ISBN: 1421527472 (Amazon)

Genre notes: history, alt-history, gender roles, internecine political madness

Would highly recommend the series Ooku: The Inner Chamber. It's an alt-history of Japan. During the third shogunate (what, around 1625 or so?) the country gets swept with the red-face pox, a pox strain that Y-The-Last-Man-style only affects males. Only 20% of the male populace survives so society (and even the shogunate) switches to a female dominated life and governance.

The cool thing is that despite the switch, Japanese history is essentially unchanged. All the shoguns and all their stories and all the Japanese events remain unchanged save for that now it's women in the same roles. So you're getting this amazing story that is basically just a trick to get you to read Japanese feudal history and think about women outside their traditional roles. And it's amazing.

And there are some seriously deeply Machiavellian nuttos up in this thing. Poisonings are rampant. Scandals, beheadings, coups, maneuvering, jockeying heirs, the whole shebang. It's madness and you want so badly for some catharsis and for the villains to get theirs. And sometimes you get that but a lot of times the bad guys just win and never suffer a single consequence.

And the crazy thing? All of this really happened because Yoshinaga is just telling you the story of Japan.

Vol 13 just came out and those 13 vols cover a space of about 250 years. I don't know if vol 14 will be the finale, but it certainly feels like it could be drawing to a close. (The series was originally slated to run 10 vols but the story was just so big.)

Theft: A History Of Music

by James Boyle, Jennifer Jenkins, Ian Akin, and Brian Garvey, with Keith Aoki

262 pages

Published by Duke Law School

ISBN: 1535543671 (Amazon)

Genre notes: music history, copyright history, IP ethics

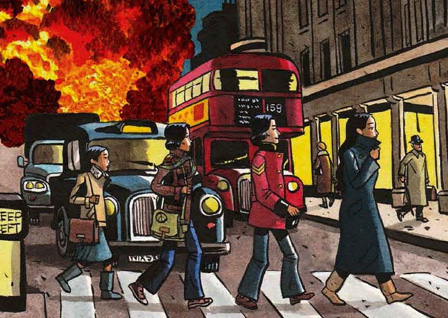

One of my favourite things about Theft: A History Of Music is how it itself continually samples/borrows/swipes from verbal and visual pop culture while discussing the rampant history of the same between basically all musicians and composers for all time. Deliriously informative read. I had been aware that all music is borrowed/sampled/swiped from (or in polite company, inspired by) other pieces and performances, but Theft does a great job of offering examples not just from a particular period but from a wealth of periods. The book drops knowledge on you in a big way but is ultra-glib and enterataining while doing so. Takes what could be an otherwise pretty dry subject and keeps it light enough so that even the lowest common denominator (like me) can be carried along to its end.

Stand Still Stay Silent

by Minna Sundberg

2+ vols

Self-published on internet

Read here)

Genre notes: post-apocalypse, adventure, ghosts, zombies, other... things...?

Post-apocalyptic zombie fiction has never been better. Which is good because the post-apocalypse is pretty well played out and man do I hate zombie fiction. But Sundberg's vision here is almost entirely unique in every way.

1) The remaining civilized world is so far limited to Iceland, fortified pockets of Norway, Sweden, and Finland, and a single island of Denmark. That's a rare and interesting setting for a story told in English.

2) The zombies aren't zombies like we typically think of zombies. There're also corrupted beasts and now a bunch of super-interesting ghosts. And an eight-legged horse that's kind of a ghost boss thing. The lore of this new world is extensive, detailed, and imaginative.

3) Sundberg's art is gorgeous. It's luscious and the way she affects mood through colour is essentially like nothing I've seen.

2017 was a huge year for Stand Still Stay Silent. The status quo shifted in a way that had fan discussion going wild with thoughts and processing and cetera. The tone and tenor of the book is unmistakeable now. This is some of the best comics around. Highly recommend. ¤_¤

Geis

by Alexis Deacon

2+ vols

Published by Nobrow

ISBN: 1910620033 (Amazon)

Genre notes: Celtic folklore, fantasy, darkness

Here's author Alexis Deacon talking about what a geis (pronounced gesh) is.

I’d grown up with this book of Celtic mythology and folk tales and they very often used this concept of "geis." The idea is that we all have these "geisa," these rules we mustn’t break, but you don’t necessarily know what they are. You go to a priest or a wise woman and they would say, you must never speak to a woman wearing purple or you must never eat five peanuts consecutively or you must never jump over one black sheep and two red sheep. You go, okay, got it, no problem–but then you inevitably do all those things. There’s no way of escaping it. Often in the stories the more things they do to get away, the quicker they bring the events about. I really liked that idea of an inescapable fate. I don’t use it in exactly that way but the core is the same.

Geis a dark fantasy series, kind of a dark fantasy version of Hunger Games or Battle Royale. But not dark fantasy in the overly chatty, grimdark, ironically self-assured manner of we've seen become common today. This is understated and confident without being jabbery. Deacon seemingly effortlessly (though I'm sure he put in plenty of effort) draws the reader into a world and story that doesn't let go. I am delighted by this book and hungry to see where it goes next—Deacon so far excels at defying expected routes and carving new paths through the adjacent thicket. And the art is reminiscent of Kerascoet's in Beautiful Darkness. Lovely, tricky, sinister work.

Goodnight Punpun

by Inio Asano

7 vols

Published by Viz

ISBN: 1421586207 (Amazon)

Genre notes: coming of age, dysfunctional families/society, road trip, magical realism

Goodnight Punpun is one of those books that I don't really like at all but still recognize as being of superlative craft. Punpun himself as well as nearly every other character in the story are basically awful. These are small-minded, violent betrayers who stalk the streets and homes of Tokyo looking desparately for wells (figurative) to poison and lives (literal) to ruin. And they all lay blame at each other's feet (which is good) while not taking responsibility for their own blame (which is bad). Punpun is the main character and he is an absolute creep and pretty nearly irredemable. And sure, we can blame some of the withering of his compassion glands on growing up in a dysfunctional family, but not all of it man. Tons of people put up with worse without sinking to the depths of his vileness. In short, I guess: I hated every minute of Punpun's revelation of self.

But then, there's the superlative craft of the book. Asano shows himself something of a genius. Diabolical perhaps, sure, but still. Goodnight Punpun is the work of prodigy. It expands the reach and the stretch of the form in so many ways and so consistently. Even Anneliese Christman's lettering is par excellence (sometimes it even blew me away).

Punpun's story is brimful of magical realism. It's almost certain to take new readers aback, leaving them few ways to understand the bizarre things that happen on the outskirts of Punpun's vision. Nevermind that Punpun himself is drawn as a simplistic cartoony bird while everyone else is rendered as detailed and (usually) ugly humans. Principals and teachers play hide-and-seek during school hours. Students pose in ritualist stasis wile drama unfolds on panel. Punpun invokes God and God appears to tell Punpun how little he cares for the little guy. And across the background of the story, a superhero battle unfolds with seeming little connection to the rest of the story.

It's a strange book, unlike anything I've yet read, but it's a magnificent testimony to the skill and creative imagination of its author. It's simultaneously disgusting and heartfelt and queer and critical. I didn't like it but it astonishes me.

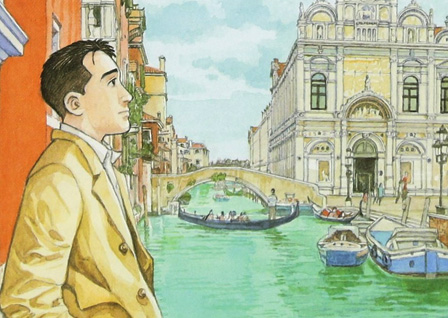

Venice

by Jiro Taniguchi

128 pages

Published by Fanfare/Ponent Mon

ISBN: 1912097044 (Amazon)

Genre notes: midlife crisis, travelogue

So Louis Vuitton hires these artists to do travel books for them, basically a carnet de voyage. They'll get ahold of an artist and send him or her to a location they've never been before and the get back a book of paintings of that place, which they'll then publish in a pricey little art book. Lovely stuff, nice for coffee tables. They tapped Taniguchi for the series a number of years ago and as Taniguchi does, he turned it into a narrative about, surprise, a man wandering around Venice taking in the sights.

The frame is that the man found among his deceased mother's things a lacquer box filled with photos and some small watercolours from Venice a long time ago. In the photos are a young woman (his grandmother?) and a child (his mother?), and occasionally, a young man (his grandfather?). As he travels around Venice he tries to match up locations with the photos and the watercolours—and along the way hopes to get some better sense of his family and their history. The narrative is slight but affecting. The real draw, however, is Taniguchi's gorgeous paintings of the city. Some are good, some are beautiful, and some are awestriking.

Here's a 4-minute video of Taniguchi talking about the project:

Audubon, On The Wings Of The World

by Fabien Grolleau and Jérémie Royer

184 pages

Published by Nobrow

ISBN: 1910620157 (Amazon)

Genre notes: biography, nature, ecology

Audubon is a sumptuous book, filled to brim with illustrations of forests, rivers, animals, and birds. It was a delight to discover the mania that lit the life of John James Audubon, a man of whom my only prior knowledge was his connection by name to the Audubon Society.

It's a well-paced jaunt through the man's later life, dwelling on episodes that confirm his infatuation with nature, his love for it, and his need to catalogue it. It's also interesting to see the 19th century environmentalist for how vastly different they are from their contemporary counterparts. In the 200 years ago, the environmentalists were hunters and one of their best tools for securing assistance in unveiling the natural world to the public (and eventually protecting it through parks and reserves) was to kill lots of animals and display them. This was Teddy Roosevelt's M.O. as well.

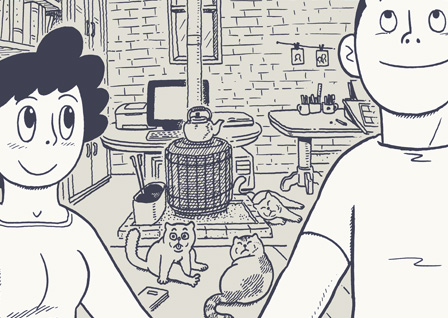

Uncomfortably Happily

by Yeon-sik Hong

576 pages

Published by Drawn & Quarterly

ISBN: 1770462600 (Amazon)

Genre notes: autobio, artists, losing your mind, marriage

I complain a fair amount about autobio, because often (probably even usually) it's obtuse or aimless or doesn't really have any real narrative trajectory. Also, unless the author is very specific in their aims, the work meanders and really isn't about anything beyond scattered snapshots of a life lived with little sense of understanding What Actually Happened. A lot of this can be mitigated by choosing a succinct pericope and essentially making your autobio comic about The Time I Did This And This Happened And Here's What I Got Out Of It.

When I first picked up Uncomfortably Happily, I winced to find it was autobio. At 576 pages, aimless navel gazing for the duration might actually kill me. Fortunately, Hong gets it. He knows what he's doing and does it well.

Hong and his wife are artists. Hong has been in comics for 14 years and his wife, a former student, is just attempting to get her career off the ground with a couple quirky children's books. They get fed up with the cost and chaos of life in Seoul so they move to a remote house up on a lonely mountain if order to work more freely. Uncomfortably Happily is the story of the year they spent there, what happened, and how it changed them.

We see their joy and interest in the move, Hong's early budding reticence, and their realization at just how much work living provincially will cost. We see how each deals with the loneliness, how cold and hard winter can really be, and how Hong begins to lose his freakin' mind. And then we see the rest of it.

Beyond the fact that Hong tells his story well, there were two principal things I deeply appreciated.

1) We see intimately Hong's struggle as an artist desiring to do work he considers valuable and of merit but needing to take on other people's contract work in order to keep the phones on and the house heated (spoiler: these things don't always get done). There're a lot of moments when there are two or three Hong's on panel talking with each other, arguing about what to do or how to live. Hong feels like a failure, constantly fielding revisions from his editor on books that never see substantial royalties. As an artist myself (and comics artist) who struggles to find time to work on my own projects and makes ends meet in graphic design, I found many moments of myself in Hong.

2) As Hong (the character in the book) gets sick from burning candles at weird ends and his depression and anxiety and anger at life overwhelm him, Hong (the author of this story) dives into non-literal representations of things. Animals talk, his comics come to life, things get kind of crazy. It was an unexpected direction and it elevated the work for me to see him portray his inner struggles with such fancy.

There might be something better out there, but for my money so far, Uncomfortably Happily is the best comics autobio of 2017 by a pretty wide margin.

My Love Story

by Kazune Kawahara and Aruko

13 vols

Published by Viz

ISBN: 1421571447 (Amazon)

Genre notes: progressive romance

It took me a couple years to give My Love Story a shot. I wasn't taken with the art. It kept me from bothering with the series. But man, you guys, I loved this story. And the art gradually became rather charming to me.

Later in this list, I'm going to recommended Horimiya, another wonderful progressive love story. I love Horimiya so much but if there's one part where it falls down a bit, it's with side character creep. Gradually as the series goes and new side characters join the book, we get less and less focus on the main couple, who are the reason why we're reading the story in the first place.

My Love Story doesn't have that problem. This is about Takeo and Yamato from beginning to end—and any stories dealing with the side characters are there to serve the telling of the main story. It's refreshing to see such a single-minded pursuit of a story about a boy and his girlfriend.

My Love Story is progressive romance (i.e. one that moves beyond the meet-cute and the will they/won't they question, exploring their life as an established couple and beyond). Takeo is a 6'6" muscular and forthright 15yo boy (who people mistake for an imposing and therefore creepy adult) and has had zero luck with the ladies despite being incredibly popular with the guys. Early in volume 1, he rescues Yamato from a groper on the train and after an initial confusion where Takeo thinks she's interested in his friend, they start dating. All this happens in the first half of vol 1. The rest of the 13 vols is exploration of their relationship given their personalities and insecurities. And it's kind of delightful.

One other aspect I appreciated was the deep love between Takeo and his best friend Sunakawa. They care so much for each other and are deeply invested in each other's happiness. It was pretty beautiful to see.

I got the whole thing from the library and binged it over the course of three days. I'd probably recommend taking more time with it than I gave.

Pantheon

by Hamish Steele

216 pages

Published by Nobrow

ISBN: 1910620203 (Amazon)

Genre notes: egyptian mythology

This is off-the-hook bonkers. Also, pretty faithful to the Egyptian myths. Therefore, off-the-hook bonkers.

You know how the Greek myths are pretty nuts? Rape, incest, Zeus being a giant animorph and screwing basically anything with a hole and making demigod after demigod (cf here). One lady he seduces by being a ridiculously charming swan.

So yeah, as nutty as Greek mythology is, it reads like Anne Of Green Gables next to the Egyptian brand of the stuff.

With that in mind, Hamish Steele's tongue-in-cheek and deeply gross comic about them is probably the perfect way to encounter and understand the Egyptian mythos. Lots of sex, lots of incest, lots of murder, and lots of other things like one god mixing his and another god's semen into a salad and feeding it to the other god and then later? that god who ate the salad? he gets pregnant and gives birth to the moon god—who had already been around for centuries at that point. ¯\_(?)_/¯

It's all very funny and very brightly told and is 100% not for non-debauched children.

1–1011–2021–3031–4041–50

51–6061–7071–8081–9091–100

MetricsExclusions 1Navel Gazing

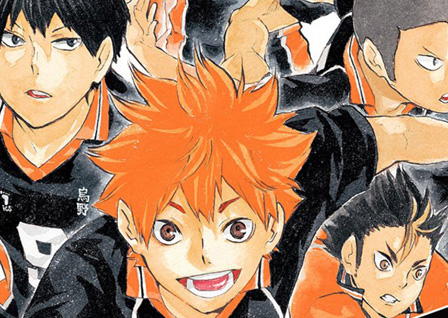

Welcome To The Ballroom

by Tomo Takeuchi

8+ vols

Published by Kodansha

ISBN: 1632363763 (Amazon)

Genre notes: sports, competitive dance, prodigy

This is a sports story and one of those sports stories about the prodigy player who got a late start on the sport and is going to quickly make up for lost time because he’s that good. It’s a common enough formula, but Welcome To The Ballroom performs its steps very well. It’s graceful on the fundamentals while throwing in some delicious variations for a pizazz that serves to elevate the rest of the story. In the five vols I’ve read so far (I’m enamoured enough that I plan to continue with the series as new vols are released), fifteen-year-old Fujita moves from entirely inexperienced amateur to gifted would-be competitor. He begins the series aimless and struggling to find an interest as he is being pushed to choose a high school to attend. Accidentally, he finds himself in a dance studio with members devoted to competitive ballroom dance. While initially embarrassed and hoping nobody discovers him there (male dancers have about as great a reputation amongst other teens in Japan as they do here), Fujita sees a video of what competitive ballroom dance is actually like and in set alight. He has a direction now and will rocket toward it through the rest of the story, meeting obstacles and overcoming them or using his defeats by them to improve himself. (See? That sports story formula. AKA life story formula.)

If you’ve read sports manga before, you’re probably familiar with the story beats, but where Welcome To The Ballroom shines is in its visual depictions of athleticism. In Polina, Bastien Vivès ably depicted his ballet dancers in spare, minimalist gestures, giving the dance a quiet fluidity emphasizing the grace and beauty of the form. Welcome To The Ballroom doesn’t remotely attempt this. Takeuchi’s dancers are vibrant, bursting with frenetic energy. They are electric and exciting and Takeuchi draws flourishes to highlight some of the emotional energy exploding beneath the skin. Fire will crackle off the clasped hands of a couple as they waltz. A character will be engulfed in flame to express his rage or passion. The skin of another will bristle and steam as their waning strength rejuvenates to pull out one last showstopper. And the sweat.

Takeuchi does one thing I’ve never seen in a comic about active characters before. They are drenched in sweat. Rivers of it pour from their hairline down their faces as they exert themselves. It’s an incredibly small detail but it goes so very far in selling the world of these competitions. The beautiful, gorgeous women in this book do not glisten. They sweat. Buckets. It’s perfect and real.

So far at least, Welcome To The Ballroom doesn’t escape its tropes or formulae, but it’s not trying to. Instead, the book is playing entirely within the established realm and doing so with verve. It’s nailing all the steps and avoiding many of the pitfalls. It’s sweeping across the floor getting it done and showing how to do it. Welcome To the Ballroom doesn’t have the emotional range or sweep of Cross Game but does make its sport thrilling even for those, like me, who don’t have much actual interest in the activity depicted.

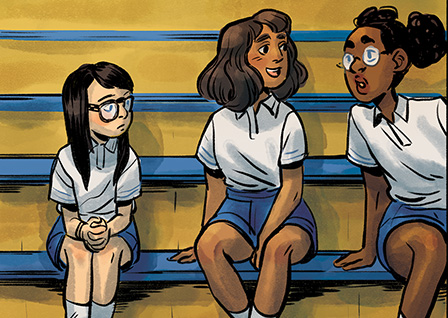

On A Sunbeam

by Tillie Walden

20 chapters

Self-published

ISBN: 1250178134 (Amazon)

Genre notes: scifi, school, coming of age, a universe without men

Walden's story here is breath-takingly beautiful. Light and darkness play against gorgeous spacey vistas, presenting empty the threat of making too miniscule the human drama unfolding in the foreround—because, really, what can matter in the face of the cosmic? Walden's answer is grandiose: the mundane daily life of a girl. And to misappropriate Walter Simonson: it is answer enough.

Walden bounces aroung through space and time to build her characters' story, relationship, and world—in much a similar way to Evan Dahm with Vattu. Only her place and time cues are a bit more overt. It can be envigourating, the way Walden lets one story inform another and vice versa. And throughout, there's this sense of quiet danger, of foreboding. Everytime I read a new chapter, I'm nearly overcome by a creeping anxiety. Like THIS is the chapter where it all goes wrong. And of course it eventually does and oh what a blast that is.

And on top of all of it, we have Walden's illustrations. Stunning work.

Can Opener's Daughter

by Rob Davis

136 pages

Published by SelfMadeHero

ISBN: 1910593176 (Amazon)

Genre notes: world-building 101

As both prequel and sequel to Motherless Oven, The Can Opener's Daughter answers questions about the rules of the prior book while expanding the scheme in delightful ways. Can't wait for the finale to the trilogy.

Thornhill

by Pam Smy

544 pages

Published by Roaring Brook

ISBN: 162672654X (Amazon)

Genre notes: art history, biography

More and more often over the last few years, comics creators seem to be willing to experiment blending straight prose with comics. There have been some successes like Russian Olive To Red King and Nao Of Brown and Equinoxes. And some less successful ones like A.D. After Death where I really just wanted the prose parts to be in comics form. Thornhill is one of those that gets the mix right, and maybe wildly right.

Thornhill will remind acquainted readers of Ruth Ozeki's novel from a few years back, Tale For The Time Being. Similarly, the book jumps between found diary entries and the reader in the present who is seeking to uncover the mystery involved. There's also some heavy bullying involved, which is the other genetic thread the two books share. That's about where the similarities end though and Thornhill has its own spooky trade to ply.

In Thornhill, present day investigations of Ella's interest in Thornhill and the events surrounding its destruction are comics, told in double-page spreads. The journal entries are in prose and unburden the many woes of Mary, an orphan who lived in the group home at Thornhill thirty-five years ago. It's a good story and a brisk read.

And Pan Smy does the thing that I wish artists would go back to doing: she letters in-world text as illustration (e.g. this) rather than using a computer font—there's nothing worse than to be reading a comic and enjoying its illustrations and come across Obviously Not Hand Drawn Sign.

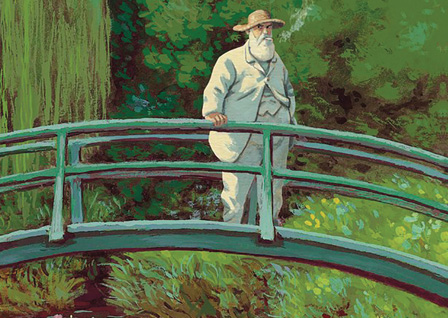

Monet: Itinerant of Light

by Salva Rubio and EFA

112 pages

Published by NBM

ISBN: 1681121395 (Amazon)

Genre notes: XXX

NBM, like SelfMadeHero, has been for the last several years been putting out these fantastic graphic novel biographies. Last year they released a Glenn Gould biography that, for me, set the gold standard for what comics can achieve when it comes to biography. Monet: Itinerant Of Light is no Glenn Gould: A Life Off Tempo, but it is still very good. Efa illustrates in a style not impressionistic be one that evokes the impressionism of the subject. It's a good story and a sad story (as most biographies must be).

Run For It: Stories Of Slaves Who Fought For Their Freedom

by Marcelo D'Salete

180 pages

Published by Fantagraphics

ISBN: 1683960491 (Amazon)

Genre notes: slavery, Brazil, magical realism

D'Saleto has created a sumptuous, frenetic book containing four short stories interacting with slavery in the Portuguese colonial history of Brazil. The stories are hard, girded in the diabolical truth of the human nature and capacity for the depraved. Still, though the slaves by nature of their bondage are always going to be on the losing side of the power struggle represented, there remains a kind of triumphalism, even sometimes in the midst of terrible betrayal and madness. Run For It offers a curious mix of the concrete tangible and the hallucinogenic magically real. It's a short but worthwhile experience.

Lighter Than My Shadow

by Katie Green

514 pages

Published by Lion Forge

ISBN: 1941302416 (Amazon)

Genre notes: autobio, eating disorders, abuse, recovery

Seth doesn't like autobio blah blah blah. We've been down this road enough that I won't reiterate. Let's just say that Lighter Than My Shadow surprised me near its middle, provoking a passionate rage and a struggle to catch me breath. More than just another navel-gazing reminiscence over the common tragedies that mark us all and leave us more dillapidated than we when began, Green's story is one that pulls back the curtain on blunt force trauma that strikes the reader in the slimmest fraction of the way it struck Green herself, and even so leaves the reader angry or furious or completely discouraged or something else both immediate and lasting. And then and then and then... at the end of it all, we find that if Green has a glimmer of hope and light ahead of her, then maybe we do too.

Hostage

by Guy Delisle

436 pages

Published by Drawn & Quarterly

ISBN: 1770462791 (Amazon)

Genre notes: biography, terrorism, kidnapping, psychology

This is going to sound like a weak recommendation but I don't mean it to be: Hostage is the perfect book to get from the library. At least it would have been for me. I don't need to own it—though I do.

It does its job really well. It relates Christophe André's real-life kidnapping from a Doctors Without Borders office and the time he spent as a hostage while negotiations for the One Million Dollars required for his release sputters and stalls and lurches and... well. The trouble is: when you're a hostage, you don't really get to do much. It's a lot of sitting there cuffed to a radiator and a lot of going slightly mad. A lot of nothing really at all. And Delisle, I think, nails this. As Anderé suffers from the sameyness of his routine, I suffered as a reader. His boredom was my boredom. Which, again, sounds like a knock on the book but it really really isn't—Delisle does exactly the right thing by not embellishing, by not turning André's time as a hostage into a thrill ride.

And at the same time, as boredom creeps in, there's this gradually rising sense of tension and anxiety. André feels it and because he feels it, the reader does too. Is today the day? Surely it will be today. What is happening? What are those noises? Will I be home in time for my sister's wedding in three months? They want how much?? Should I try to escape? I don't know where I am or the language at all. I don't know if everyone around is in on it or if I call help loudly enough will I be rescued. I could attempt an escape but I might just complicate things since my release will surely happen tomorrow. Oh, I... I'm going to die here aren't I?

The whole experience was excruciating and delicious and now that the tension is gone because I know exactly how everything plays out, I don't see myself reading the book again. It was great and while I don't regret owning it (because ownership means I can lend it), in retrospect I would have been fine checking it out from the library.

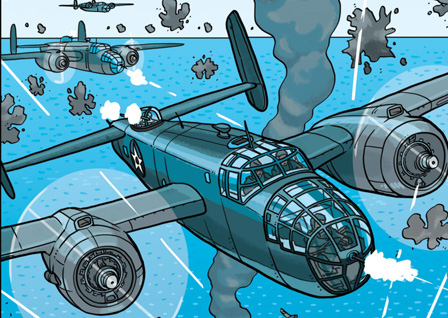

In This Corner Of The World

by Fumiyo Kouno

450 pages

Published by Seven Seas

ISBN: 1626927472 (Amazon)

Genre notes: day-in-life, wartime, WWII

I've been waiting for a long time for more work to import from Fumiyo Kouno (her Town Of Evening Calm is an old favourite); I'm only sad that it took the release of her movie here to inspire a publisher to get on that ball. In any case, In This Corner Of The World is a treasure cut from the same vein as Town Of Evening Calm and concerns, in its way, the Hiroshima event.

Suzu grows up in a town in Hiroshima. As a teen, the war sparks up and a man who remembers a happenchance meeting when they were kids comes from the nearby coastal city of Kure to ask for her marriage. Because that's the way things work, Suzu moves to a strange city with a strange man where she will live with and work for the house of a strange family. As the story moves inexorably toward the Moment, we see daily life getting gradually impinged by the rising tide of war. It's a study in how the commoner interacts with a gradual increase of heat and pressure—and what it means to lose, badly.

Vinland Saga

by Makoto Yukimura

9+ vols

Published by Kodansha

ISBN: 1612624200 (Amazon)

Genre notes: historical fiction, fictionalized biography, Vikings, religion, war

Vinland Saga is basically the series to be reading. It's incredible. The only reason it's as low as it is on this list (still pretty high) is that 2017's vol 9 is just the beginning of a new ar (the Baltic Sea War) and it's anyone's guess how that'll play out. Anyway, I'm just going to give my standard pitch on why you should be reading Vinalnd Saga.

Vinland Saga is a graphic novel series from Japan about vikings and Odin-worship and Christianity and warrior culture and pacifism and revenge and redemption and having scary dreams about all the hundreds of people you've killed. It's loosely biographical, telling the life story of Thorfinn Karlsefni, his wife, his founding of a settlement in Newfoundland, and his interaction with the Viking king Knut.

So here's this kid named Thorfinn who's set on avenging his fathers death. His dad was this epic warrior, the best of the best, but he gave it all up for something more powerful and became a pacifist. Then because when you're a Jet, you're a Jet all the way, his old gang of super tough vikings have him assassinated. So Thorfinn's been part of this mercenary band since he was six, waiting for his chance at revenge. He's become this monstrous fighter, basically a superhero of murder but it's okay because vikings are all about battle and war.

Then events conspire so that his reason for living vanishes. There's no longer any vengeance for him. He's rudderless until he remembers some stray words his father spoke. This combines with a lot of talk about Christianity (if you remember history, this was a time of great mashups between Odin-worship and the Christian mythos).

So suddenly, after 1700 pages, we finish Chapter 54, which is titled "The End Of The Prologue." The book has been 1700 pages of brutal war. It's a bloody violent action-lover's dream (with a sprinkling of religious and political talk to make it feel not entirely like a dumb superhero book). And suddenly, [END OF PROLOGUE SPOILER] the action hero—this unstoppable warrior—takes a vow of pacifism, becomes a slave on a plantation, and starts living toward the goal of building a world of peace.

I mean think about that, it's pretty brassy to put together what is basically a brutal action adventure story and then suddenly after 1700 pages get your readers on board for a book about a guy who won't fight back. It would be like Christopher Nolan making The Dark Knight Rises into a movie where Bruce and Selina wander around Gotham City chatting Before Sunrise-style and at one point they get mugged and Bruce gives up his wallet and maybe offers the mugger a job at Waynetech.

I find the book fascinating, not only because of how it incorporates mature and varied discussion of faith and its consequences (which are pretty much totally unexpected in the genre), but also because it implicates the reader in Thorfinn's violence. You hear that kind of thing a lot, a book or movie or videogame implicates the reader in this or that, but I think Vinland Saga really drives it home after Thorfinn dumps his old self to become a man of peace. You have this warrior who's both incredibly skillful and incredibly savage, who could kill ten men in a flash. And he gets confronted with unjust brutality or theft and you just want him to strike back, you want those who oppose him, those who would abuse him, to know the fear they ought to have for him. You want catharsis and vindication—and because you're wanting violence and the hero instead offers the other cheek, you're left feeling the power of that decision.

So far, vol 7 is my favourite of the bunch for its truth-to-power moments, and the conversation between King Knut and Thorfinn where Knut (the Christian) says that God has failed us and that we've got to subjugate the world with terror and violence in order for some of us to know peace, and Throfinn (the pagan) is like, "Nuh-uh, bruh."

1–1011–2021–3031–4041–50

51–6061–7071–8081–9091–100

MetricsExclusions 1Navel Gazing

My Favorite Thing Is Monsters

by Emil Ferris

2 vols

Published by Fantagraphics

ISBN: 1606999591 (Amazon)

Genre notes: monster movies, fiction through diary, the '60s, prostitution, the Holocaust, mystery

Originally, vol 2 of My Favorite Thing Is Monsters was slated for a 2017 release. Obviously that's been revised and so I'm not quite sure what to do with it. So much of my evaluation of the book is going to hinge how it wraps up its ambitious story. It could end up Top 10 material or it could slip, but for now, I'm just going to let it sit around 30 or so, which is still a strong place.

MFTIM does some things very very well. The use of ballpoint pens (or possibly pen-emulating brushes) is awesome. Ferris' use of colour here is almost incredible. As well, the bouncing around of the narrative and the discrete release of revelations works very well. On the other side, page and panel flow can be awkward and about 30% in I gave up trying to guess in which order I was meant to approach text blocks and balloons. As well, I struggle to buy that the narrator/artist is ten years old; there's things that feel like discrepancies (I guess) where she's handing out Valentine cards in class (a pretty ten-year-old thing to do) but then a week later being threatened with actual penile penetration by classmates. Maybe that does happens in fifth grade (!?) but I know I wouldn't have had the physical development required to have sex with anyone back then, and I was old for my grade.

On the other hand, Karen from the first proves that she has an overactive imagination that she is full-well ready to believe as fact, so maybe that will play a role. I don't know. But I do know that like most everybody who read vol 1, I am hungry for vol 2 to see how this whole terrible circumstance is resolved.

Ragnarok

by Walter Simonson

2+ vols

Published by IDW

ISBN: 1631400681 (Amazon)

Genre notes: expansion of Norse mythology

Walter Simonson wrote and drew (to me) the very best Thor comics of all time. The marvel series always left me unaffected and often seemed too hokey. Then Simonson picked up the reins back in the early '80s and the book blew up. Thor was interesting, grand, noble, and larger than life. Simonson had a knack for the character and for his world. That run of comics (from Thor 337 through 382) would be the only time I truly enjoyed the character.

When I heard that Simonson was doing a new Thor book, I was interested. When I heard it was unrelated to his Marvel work, I was even more interested.

I didn't know what to expect but I did expect brilliance. And in the first vol, SImonson ... doesn't quite deliver. It's fine. It has some great art. It has some interesting concepts—e.g. Thor is basically undead after hundreds of years and has no lower jaw. But it was missing some of that spark that made me fall in love with Thor in the first place. As it turns out, this is because vol 1 is essentially prologue. It's all set-up.

Vol 2 delivers on that set-up and makes me so happy to be following this book. In honesty, probably vols 1 and 2 together form the prologue for the rest of the book. Or maybe Act One. I don't know how long this is intended to be. In any case, these 2 vols form a complete story that seems to be just the start of something epic and hopefully long and almost certainly amazing.

For synopsis: Thor has been asleep and imprisoned for a long time. The gods are all dead. Darkness and fell powers rule the earth. Ratatosk tricks someone into waking Thor—and now his long Monte Cristo-like quest for vengeance and mourning begins.

Monograph

by Chris Ware

280 pages

Published by Rizzoli

ISBN: 0847860884 (Amazon)

Genre notes: autobio, retrospective

Monograph is part memoir, part career retrospective, part celebration of all the weird projects the author got into along the way. As a monument to Self, Ware creates something both lowbrow and highbrow—and ridiculously large. I can't imagine more than a slim percent of those who purchase the volume will actually read the entire thing for all its miniscule text. For those with only a tacit interest in Ware or his self-history, the book still boasts some great comics. I was particularly happy to find my favourite of all his works, a one-page story he did about this kid whose older brother went to war and never made it back. It's a haunting piece and explicates loss in a clear-hearted way.

Furari

by Jiro Taniguchi

204 pages

Published by Fanfare/Ponent Mon

ISBN: 190800729X (Amazon)

Genre notes: wandering, mellow story, perspectival shifts

Furari concerns an 18th-century man whose hobby in his early retirement has been measuring the distance between places in the city by counting his steps and perfecting the regularity of his gait. Along his way he is often caught up in the spell of his imagination, considering the creatures he runs across and how the world must look to their perspective. Turtles, cats, hawks, elephants, dragonflies, etc. Observing the people and animals and natural phenomena in his path gives him an idea for the construction of a device to help him accurately measure distance and he eventually receives a command from the Shogunate to measure and map the whole of the nation. But all that is really just an excuse for Taniguchi to draw feudal Japan and the wide variety of life that filled up the place. His drawings, as usual, are beautiful and he sometimes uses floating world style perspective and clouds to breath a sense of legend into his pages.

New York Stories

by Kevin Huizenga, Tom Gauld, Tillie Walden, etc.

74 pages

New York Times Magazine, 4 June 2017 edition

Read here

Genre notes: journalism, New York Times metro desk

If the New York Times would release an all comics magazine every Sunday (without a dip in the quality present here), I would subscribe to their newspaper. This was delightful.

Jornalistic stories in comics have been a thing for at least a little while. I first encountered the genre in Joe Sacco's Palestine around 1999. Even that was a bit of journalism mixed with autobio. Certainly there's a place for the ??? in journalism, but generally we look for stories about someone other than the reporting journalist. I think I first noticed a surge in non-??? journalistic comics a couple years back with the rise of The Nib. Certainly there were plenty of stories about What It Was Like For Me Colouring Black Characters For Marvel and The Time I Visited A Prison Island and My Experience With Sensory Deprivation (each interesting stories), but then there were the non-??? stories about what's happening with the economy in San Francisco, how people interact with the C-word, and the strange ruin of Fort Ord. I was glad to see this trend because it revealed one more cool avenue for comics storytelling.

When I went out of my way to find a copy of this NY Times Magazine edition (I honestly had trouble finding a place to buy one), I was hopeful but guarded. Anthologies are rarely Very Good. They're usually a mix of good and bad and end up leaving a mediocre taste in my mouth. The Nib's collection a couple years back (Eat More Comics) had some amazing stories and some just plain crappy or boring or eye-rolling comics. I was glad I had gotten it but I also wished it was half as long and that its editor was more discriminating.

The NY Times Magazine all-comics edition evades this trap. They either got lucky or just have a better editorial team. There is still some variation in quality between stories, but even the worst story in here is still Good. One of my favourites is about these two people in Harlem who just sit at their windows and watch the world go by. The artist, Bill Bragg does this thing like Here and 750 Years In Paris do, where he takes the same exact scene and camera angle and lets time wash over it. Basically you spend a day looking out this woman's window. One of my favourite parts is when it begins to rain in the early evening. The store windows have lit up and the ground darkens with wet and then a puddle forms. In half of the puddle, you see the reflection of the store window. It was such a great detail that it sold me on the comics in a way that I wouldn't have know I was missing out on had it not been there.

This magazine is no longer in print, but you can still read it for free on the NY Times site.

A Thousand Coloured Castles

by Gareth Brooks

208 pages

Published by Graphic Medicine

ISBN: 0271079274 (Amazon)

Genre notes: medical condition, dementia

Myriam is seeing things that defy believability, but really of course she would. Castles pouring from the sink, girls in motorcycle helmets melting into the ceiling, men with ladders for heads, a naked boy next-door playing with exotic parrots. The usual for the British suburbs, of course. But something more is going on. In Myriam's mind or in reality, it hardly matters.

Master Keaton

by Naoki Urasawa

12 vols

Published by Viz

ISBN: 1421575892 (Amazon)

Genre notes: mystery, archaeology

A few years ago, I gave Master Keaton a shot (three vols worth), but it didn't click with me. I'm a big fan of Urasawa and the stories were fine and all, but there was no enduring narrative. A reader could start anywhere and read another Master Keaton yarns and leave entirely satisfied. It's like reading those short Hercule Poirot mysteries in that one story doesn't inform the next story. There was no over-arching direction for the book.

Seeing that the series wrapped in 2017, I thought I'd binge the whole thing in a fit of completionism. And largely, my opinion endured. Through vol 11, the series is comprised of short, unrelated mysteries and adventures. Kind of like watching MacGuyver. There were a couple recurring characters and occasional references to past cases, but not much. Then vol 12 hit and the whole thing is a volume-long culmination of the Keaton mythos, resolving so many of the things dangling around since vol 1. That was satisfying. What a nice little ride.

Usagi Yojimbo

by Stan Sakai

264 pages

Published by Dark Horse

ISBN: 1506701876 (Amazon)

Genre notes: historical fiction, zoomorphs, samurai, educational

Usagi Yojimbo is the story of a fictional, idealized, totemic, and somewhat historical Japan. It is a story told by following (primarily) a single wandering ronin as he follows the way of the samurai, seeking enlightenment, honour, justice, and the beauty of living. Due to his wandering nature, the reader encounters a breadth of stories, regions, and cultures. These tales unfold circa 1627 and create, despite their (sometimes) almost mythical hue, a worthwhile vantage into real and historical Japan.

Sakai peppers his narrative with the fruit of a lot of research. The most popular of his stories, “Grasscutter,” begins with a lengthy-though-entertaining excursus into the mythological origins of Japan and her people. A shorter story, “Daisho,” explains the craft with which the samurai’s sword-pair is forged and the importance those two swords (called daisho) hold to their owners. Other chapters include overtly educational bits on kite-making, pottery-making, and the intrusion of the West into the Far East. And even when he isn’t completely halting his telling in order to instruct the reader, Sakai weaves a story that posits a seamless, discreet form of education—taking part in the story by simply reading it, Sakai’s audience is constantly learning more and more about a dead and foreign culture.

One of Sakai’s great talents is in his visual storytelling. His art flows naturally and his panel design is masterful. Some of the most beautiful pages are silent and filled with panels; each of these panels illustrates part of a picture-story that initially seems unrelated to the narrative intent but ends up providing context or mood for everything that is to follow. Sakai’s art has a wonderful, lyrical quality to it and it’s incredible that he’s been able to maintain his more-than-twenty-five-year schedule of producing one chapter per month. He really is one of the best creators in the medium.

31 vols is a lot to take in. If you want a nice place to start, to see if this is a book for you, I'd recommend read vol 28, then 29, then 30, then 31 and backtracking from there if the story suits your tastes.

Vattu

by Evan Dahm

3+ vols

Self-published

Read here

Genre notes: adventure, politics, anthropology

While Rice Boy was fascinating and inventive and Order of Tales offered a superb yarn, Evan Dahm's Vattu is his most ambitious story yet—a multithreaded, complex narrative about the crossing of cultures, imperialism on the verge of post-imperialism, the semitotics of identity, and how language shapes us.

While Rice Boy's colours were flat and Order Of Tales was black and white, Vattu is vibrantly coloured with a perfection of details. It's a beautiful book. I'm hungry to see the story complete if only because I 1) love the satisfation of a story concluded and 2) can't wait to see more stories in Dahm's world.

Jane

by Aline Brosh McKenna and Ramón K. Pérez

224 pages

Published by Archaia

ISBN: 1608869814 (Amazon)

Genre notes: adaptation, drama, romance

As an adaptation, Aline Brosh McKenna's interpretation of Jane Eyre as a contemporary story does exactly what adaptation is meant for. Not slavish reenactment but lucid extrapolation. There are plot points that have been excised or revised, all to the end of giving Bronte's masterwork a new spin and a new chance to move and thrum.

It's a delightful work—and one that wouldn't have succeeded half so well were it not for Ramón K. Pérez' illustrations and artful storytelling. A good artist might have made the story stand. A master like Pérez makes it sing. His choice of frame, of camera, of action is all amazing and breathes life into a story that many of us know quite well by now.

This is one of the most beautifully drawn books I've read this year in terms of pure cartooning talent.

1–1011–2021–3031–4041–50

51–6061–7071–8081–9091–100

MetricsExclusions 1Navel Gazing

Mighty Jack

by Ben Hatke

2+ vols

Published by First Second

ISBN: 1626722641 (Amazon)

Genre notes: adventure, adaptation

One of my favourite books to recommend younger readers (from Kindergarten to about fourth or fifth grade) is Ben Hatke's Zita the Space Girl. It's a buoyant story about a plucky, wonderful, and sometimes not very kind little girl who gets sucked into a tremendous space adventure. Hatke wrapped the trilogy a few years back and I've been waiting for his next major work since then. He's switched things up a bit, doing a couple picture books and a shorter graphic novel (Little Robot) that's probably aimed at readers a little younger than Zita was. These last couple years though, he brought us Mighty Jack, a sort of riff on Jack And The Bean Stalk. And you know what? It's better than Zita.

Mighty Jack proves that practice can make you better at what you do. Really, we already saw this at work with Hatke, since each volume of Zita was more accomplished than the one before. Mighty Jack is well-paced and more lithe. It's a fun and dangerous adventure, aimed probably at the same range as Zita, maybe a touch older. And yeah, I say the book is aimed at young readers, but despite the fact that my kids love it, I'm the one who is salivating to find out What Happens Next.

Happiness

by Shuzo Oshimi

6+ vols pages

Published by Kodansha

ISBN: 1632363631 (Amazon)

Genre notes: vampires, being a teen, there is no happiness in this book…yet

Shuzo Oshimi, the nutball (in an awesome way) behind Flowers Of Evil, Inside Mari, and Trail Of Blood) is putting out maybe the first vampire story that's caught my interest. There's a solid mix of stuff common to the subgenre and stuff that is more in line with Oshimi's unique set of interests.

Beyond the many weirdnesses at play, Oshimi draws the heck out of the book. He sometimes veers into straight-up surrealism when depicting the experience of his vampiric characters—and it works colossally well.

I wasn't sure I was onboard but because it was Oshimi, I thought I'd give him 3 vols to win me over. By vol 3, I was interested enough to keep going. By vol 5, I was in the bag and I can't wait to see how he subverts expectations in vol 7.

A Bride's Story

by Kaoru Mori

9+ vols

Published by Yen Press

ISBN: 0316180998 (Amazon)

Genre notes: history, anthropology, romance

In A Bride’s Story, Mori deposits the reader leagues away from the British romance of manners she crafted in Emma, instead exploring rural and nomadic life along the Western track of the Silk Road during it's diminishment in the Great Game era. While Mori has so far largely focused her attention specifically in what is probably central Kazakhstan, near the expanding Russian border and off a bit from what used to be the Aral Sea, she's been simultaneously following a narrative track that allows her to explore increasingly Muslim lands as she follows a character's trek around the Aral and south around the Caspian on his way to Ankara in Turkey. The cultures she describe are rich in a heritage and practice that will be largely unfamiliar to the average Western reader. This is a land of yurts, shepherds, big families, khanates, delicate carvings, intricate weavings, and ornate embroideries. Much of A Bride’s Story serves as educational documentary, explaining carefully the importance of these facets of the peoples the story concerns—and it’s a mark of Mori’s talents that these lessons are never dull. The story, while pausing its plot elements for a description of tribal politics or the importance of rug-hanging, is built and embellished and given life through these brief excursions.

The most obvious of the more unique aspects of the culture Mori explores in A Bride’s Story is this people’s tradition for youthful marriages. The author explains in her endnotes to the first volume that the average marrying couple in the region would have been fifteen to sixteen years of age. For dramatic purposes here, she adds and subtracts four years from the average for her principle couple—though in a subversion of the trope, the bride is twenty and the groom only twelve. This creates numerous opportunities for thoughtful consideration of how different cultures might deal with the man/woman dynamic—as well as plenty of related awkwardness for both reader and characters alike. Amir, the bride, is often torn between mothering her young husband, Karluk, and approaching him like a young woman who is gradually falling in love. Further adding to the dynamism of the work is the fact that at twenty years old, Amir is viewed by her society as an old maid and there is no small concern that Karluk may have been slighted by being given a wife who will likely bear him few children. Amir, therefore, is eager to please her husband and new family, which gives Mori ample opportunity to display the bride’s considerable talents. Amir hunts, herds sheep, embroiders, shows a talent at horsemanship to rival any of the men in the family, and has a good decorative sense.

A Bride’s Story offers contemporary readers a delightful opportunity to exercise the skill of reading and enjoying a text without finding moral agreement with the circumstances, actions, or particulars of its protagonists. For this reason, A Bride’s Story may even be desirable to get into the hands of younger readers (despite some occasional nudity—or substantial nudity once vol 7 rolls around since much of that volume occurs in a women's bath house) if for no other purpose than to promote this critical ability at an early age. Mori makes this an elementary text for this kind of exercise. Almost no American reader will approach the text thinking it good or appropriate that a grown woman should marry a boy who is only straddling the boundary between childhood and puberty—yet that is the circumstance this culture forces on its two very winning protagonists. Further, the reversal of the autumn-spring relationship trope presents opportunities to consider the contemporary sexual politic. As well, it’s interesting to see a situation in which a clearly competent, intelligent, and mature woman willingly places herself ultimately under the authority of a child (a kind child who evidently cares deeply for his new charge, but nonetheless…).

The last two volumes of A Bride's Story have focused on longtime side character Pariya, the brash, plain-spoken, and largely talentless young woman who became one of Amir's earliest friends. After a good pile of abortive matches, she's found a suitor who she neither scares off nor opposes, but the attack on the village in vol 6 destroyed her house and with it all of her wedding preparation and dowry. Vols 8 and 9 concern her bride's story and explore whether there might be a romantic future for her as well.

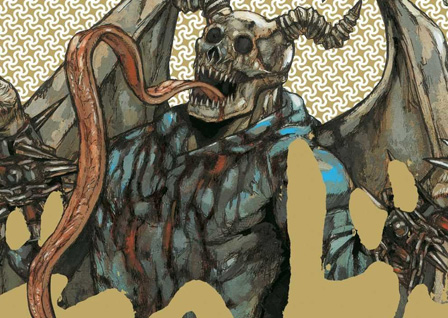

Dorohedoro

by Q Hayashida

21+ vols

Published by Viz

ISBN: 1421533634 (Amazon)

Genre notes: horror, adventure, grotesque, comedy

I don't even know what to write here. Dorohedoro is wrapping up and if you're already this far in then of course you're in for penny and pound. If you haven't yet tried the book, give it a shot please (if you can handle blood, violence, and comedy). It's one of the most creative books I've ever encountered. I can't even really begin to explain the book. you kind of just have to dive in.

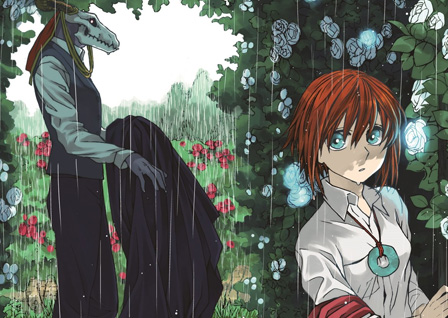

The Ancient Magus Bride

by Kore Yamazaki

264 pages

Published by Seven Seas

ISBN: 1626921873 (Amazon)

Genre notes: faery fantasy

The Ancient Magus' Bride is a funny mix of your typical fantasy story about a young but preternaturally gifted apprentice coming into her gifts built on the foundation of some bizarre and skeevy stuff—which actually makes the story interesting instead of just one more example of a long-mined-out trope.

Chise Hatori has been able to see beings from the fey world all her life. After abandonment by her father and the suicide of her mother, young Chise was left at the mercy of her relatives who passed her around and abused her. In her later teens, Chise sells herself into slavery to a mage (exactly how bad her life had to be to get her to that point, we don't yet know save for that damn it must've been bad). Elias, a half-fey (he has a deer skull for a head), half-human (or something) mage purchases her at auction and while he can do whatever he wants with her, he gives her a home and a routine and tells her she matters and begins training her to be a mage. It's not all sunshine and roses of course and Elias has ulterior motives and even shares some of those with Chise, but this begins her adventure into a new life that will change her and change Elias and change the world around them, hopefully for the better.

Oh, and there's the strange fact that everyone in the fey world (including Elias) keeps referring to Chise as Elias' bride. We don't yet know if their use is the same as our use of the term, but it's definitely an odd point and discovering what exactly this means is a large part of what's lurking in Chise's ongoing story. Everytime Chise corrects the fairy people that no she's not his bride but only his apprentice, they always shrug and say "whatever, same thing!" It's an engaging book and the art is crisp and, generally, fun. In a lot of ways, it feels like a much more shounen version of The Girl From The Other Side.

Erased

by Kei Sanbe

4 vols

Published by Yen Press

ISBN: 031655331X (Amazon)

Genre notes: time travel mystery

Erased is one of the series I'm most excited to see wrap in 2018. I've even kept away from the Netflix adaptation so I can approach the comic's conclusion with fresh eyes. So twisty, so turny. There's this moment late in vol 3 where I was like, "Wait what? What did you just do Kei Sanbe you bastard?"

For those unfamiliar with the premise, Satoru is kind of a loser manga creator who has this one weird "power." He'll be going through life and sudeenly, he'll find that time has rewound about a minute or so. This let's him recitify some unknown thing, if he can figure out what he's supposed to have noticed. So he saves a kid here and there throughout the course of his life. No biggie, right? Then something happens and he rewinds not just a minute or two but 20 years or so. Suddenly, he's in fifth grade with the mind of his sad sack adult self. Kind of a murder-mystery version of A Distant Neighborhood.

Horimiya

by HERO and Daisuke Hagiwara

9+ vols

Published by Yen Press

ISBN: 0316342033 (Amazon)

Genre notes: progressive romance, romcom, high school

Horimiya is the cutest thing ever. Basic idea: The story is about 1) Hori (the girl), a gorgeous high-achiever who outside of school wears sweats, no makeup, etc (basically she is a real person and is not 100% made up 24/7 but that is weird either in Japanese cultural or maybe just in Japanese pop cultural confections like this comic) and about 2) Miyamura (the boy), who in school appears a gloomy four-eyed otaku but outside of school is a good-looking, pierced-and-tatted dude who catches girls' eyes. They accidentally discover each other's real selves and it goes from there. They become friends and help keep each other's other selves' secret from the swirling populace of the highschool dramamill. And then the boy/girl thing starts to happen.

Horimiya, the book's title, is a portmanteau of Hori and Miyamura. Kind of, I guess, like Brangelina.

Among the neat things is that Horimiya is a progressive romance (i.e. one that moves beyond the will they/won't they question and explores their life as an established couple and beyond). It doesn't happen right away and the book follows their awkward courtship before courtship, the sort of mutual friendzoning in which they're each terrified to find out exactly what they mean to each other—but it moves beyond that and into the struggles, joys, and rhythms of life as a couple.

It's good. It's real good. And I laughed a lot. The artist's ability to capture expressions is great. The only weakness in these later vols (and why it's fallen in place since last year) is that as the cast grows, the book gives a fair amount of time to their love stories as well. And honestly? I'm not here for them. I'm here for Hori and Miyamura. These other stories feel like a distraction. They're not bad, but they aren't Horimiya.

What Is Left

by Rosemary Valero-O'Connell

36 pages

Published by ShortBox

Genre notes: sci fi, human connection

In the future, spaceships may be powered by the memories of people. After an accident in space, a woman gets caught in the memory core of the ship she works on and is trapped as a ghost within the memories of another woman.

Spacey. Gorgeously illustrated. A nice story playing with what it means to see another person, what it means to know them, and the very human desire to ourselves be known.

Samaris

by Benoit Peeters and Francois Schuiten

96 pages

Published by IDW

ISBN: 1631409425 (Amazon)

Genre notes: twisty urban fantasy

It's always cause for interest when a new Schuiten/Peeters Obscure Cities book comes out. Not only are the illustrations superb and, often, jaw-dropping, but the way the tales spin out often plays with interesting concepts.