Pity the books that came out in the pandemic years. Hm, maybe let's start differently.

We're all too much prisoners of the cult of the new. We're trained and we in turn train each other to only truly perk our ears up when discussing the recent. Recent films, recent games, recent books, recent songs.

Nobody wants to read today in 2023 a list of the best graphic novels of 2016, even though a critic today in February 2023 would have a much better chance of having read all the good stuff from 2016 than a critic in December 2016. Except for that a 2016 critic was already gearing up to start reading 2017 books, and any 2016 books they read in 2017 they've probably forgotten ever existed because it wasn't part of their year-end list. (Just pretend I'm not speaking from experience here.) I guess also, a good chunk of those 2016 under-the-radar critical masterpieces might even be out of print now. (Did you know that Cross Game is now out of print? Isn't that just insane?)

I feel I'm losing the thread again. Let's start over.

Hey there. Been awhile, eh? I'm exactly three years late with this thing. And also, this edition of The Annual Thing will be a little different from those in the past.

While for marketing reasons I title these lists as the "Top 75" or "The Best Comics Of The Year" (because that's the kind of thing that people want to see, they want the combat and conflict of the Best vs Not The Best, not some wishy-washy list of one guy's recommendations), I've also been pretty up front that (in light of human subjectivity combined with inability to read everything) the whole concept is a bit ridiculous. That is more the case for this present list.

I publish my annual best-of-the-year list every February. Not ideal for Christmas shoppers or big clicks, but it's always felt more ethical, more responsible, giving me a chance to better do the due diligence of checking out as much as possible from the year in question. In February 2020 I had just posted my 2019 round-up, the 75 best books I'd seen from the year. One month later, our kids were locked in the home with us, attempting to do school over Zoom while my wife attempted to teach school over the same.

Those early months of the pandemic exhausted me, and in strange ways. They robbed me of the joy I took in reading comics. In a normal year, I would read around 450 graphic novels, which would easily give me a wide selection of books with which to fill a top 75 year-end list. By the time February 2021 emerged around I'd only read 30 comics from the previous year. I'd hoped that as the pandemic rolled on, things would more or less return to normal and I'd be back to reading voraciously.

That hasn't happened. I'll still go months without reading a comic. Then I'll have a nice month where I read 12 books (which is still not many), then I'll dry up again. I'll get books from the library, run out all my renewals, get my account locked, and then still not have finished them. So who am I to put out a best-of list?

But comics are still good and I've still read some good ones! AND I like sharing that joy. So this year, this list is emphatically not a best of list. This is very simply My Favorite Comics, Graphic Novels, And Manga from the last 3 years.

They're still ranked but even that's more loosey-goosey than normal, because it's a little tough to keep in mind the details of a book I read in Nov 2020 well enough to compare it to something I read a month ago. I had even finished this list and was looking at my shelves for something to read and found a book that I'd forgotten had even come out in the covered period (that book now sits at №17). But we do the best we can with what we can.

At the end of the day, this isn't about upsetting anyone because their favorite from 2021 isn't included. Instead this is just one more opportunity to celebrate comics and remember what a wonderfully diverse, robust, and warm-hearted artform we've inherited.

SupportNear MissesNavel Gazing

My Best 100 Comics of 2020-2022

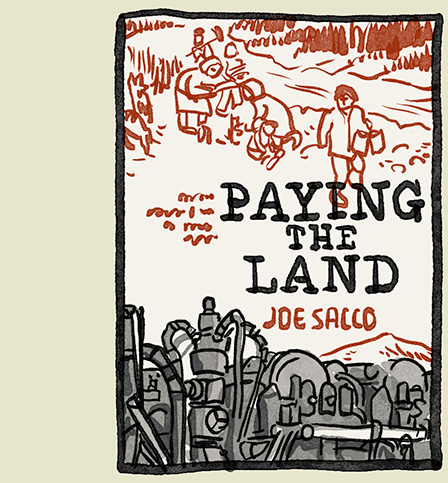

Paying The Land

by Joe Sacco

272 pages

Published by Metropolitan

ISBN: 1627799036 (Amazon)

Joe Sacco has become these last 30 years a chronicler of doom. Beginning in 1993 and shuffling through publishers from Fantagraphics to Drawn & Quarterly to Metropolitan, Sacco has given voice to those whom the wheel of oppression grinds and grinds. The one thing Sacco's books never fail to do is fill me with impotent rage. They make me hate people. They push me to believe the human experiment an abject failure. And Paying The Land is no different. He may sprinkle in moments of hopefulness, dashes of simple human beauty, but the doom chronicle moves on, its pace inexorable.

In Paying The Land, Sacco wanted to get away from the war-torn, away from the cycle of violence pitting weaponed neighbors against less-weaponed neighbors. After several books in Palestine and several in Bosnia, the plight of the native tribes in Northern Canada sounded like a nice break. Only... I think I may have felt more rage in Paying The Land than in any of his earlier works. That could just be proximity and forgetfulness, but man was this book a rough read.

I think Sacco's storytelling and journalistic excellence are in top form here. It might be his best book, focusing on colonization, assimilation, and the burgeoning attempt at decolonization. But it's really hard to take, seeing the systematic way a people were disintegrated, seeing their culture dismantled - all on the alter to the twin gods of capitalism and white supremacy.

Sacco's getting older (compare his self-depiction in Palestine with that in Paying The Land; I feel like I've watched an old friend grow old). He'll be 60 in a couple months. I don't know how many more of these books he'll have in him, but I hope for at least another two. More if we are fortunate. We certainly don't deserve these books, but I'm glad we have them and hope they'll help push us in better directions.

Nod Away

by Joshua Cotter

2+ vols

Published by Fantagraphics

ISBN: 1683964608 (Amazon)

When vol 1 came out seven years ago, it began a strange, often opaque science fiction story about a society wrapped up in connective mind, an innernet allowing constant and instant mental access to, basically, an internet of minds. It was a quietly awestriking book, skirting into horror at times, but most pronouncedly a drama of persons.

A couple years ago in a discussion of the idea of transcending genre, I thought about genre works that are thoroughly a product of their genre but employ techniques exterior to the genre to increase perceived value of the story. The converse is literary fiction that employs genre motifs in order to likewise increase value. Nod Away feels less like a science fiction story and more like a literary work that dances with sci-fi elements to round itself out. That becomes more apparent in vol 2.

Anticipating the arrival of vol 2, I decided to revisit the first book in order to refresh my sense of characters and predicaments. It was a good time. Cotter's work blends wry, amusing, and everyday conversations that build character and relationship, and while it would rather spend time with characters being characters than deal in moments of catastrophic disaster, vol 1 does end midair—and the drop is sudden.

Vol 2 picks up in that final moment and then bends time backward 40 years to show us how we got there. And that How We Got There is really just 300 pages of normal, everyday human relationship. The sci-fi aspect goes almost entirely dormant while we watch a graphic artist hope to kickstart a relationship with a French hippie girl and then get into... farming? Still, the weirdness and tech are creeping around the corners, reminding us where we are. And then we catch up.

Early on, Cotter said (I think) the book was to be 7 volumes. After volume 1, I thought this is going to be a fairly interesting read and wanted to know where it was going to take us. After volume 2, I decided Cotter is actually probably a genius auteur and I'll be happy to go wherever he'll take us.* In any case, Nod Away is one of the books of the 2020s for me.

*and I say that as someone who didn't like Skyscrapers Of The Midwest at all.

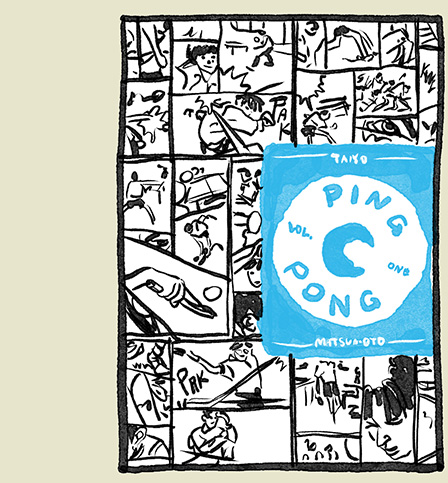

Ping Pong

by Taiyo Matsumoto (translated by Michael Arias, lettering by Deron Bennet)

2 vols

Published by Viz

ISBN: 197471165X (Amazon)

Taiyo Matsumoto's Ping Pong is a frenetic story following five top-class high school ping pong players as they each strive to balance their desire to win with their love of the sport. Peco is a natural ace but has grown sloppy with too many easy victories. Dragon is the indomitable champion backed by the best gear, tech, and training. Demon isn't a prodigy but has trained hard to beat Peco into submission. China has been kicked off the Chinese national team and hopes that winning the Japanese nationals will begin his redemption arc. Smile has lost his love for the sport because his best friend Peco goes easy on him. And everything hinges on what Smile does next.

Matsumoto's virtuosic illustrations trade heavily on dynamism, making the smacks and dives burst from the page. Part of that art is the sound effects Matsumoto uses—and so important are they to experiencing the story that in adapting the book to an American audience, letterer Deron Bennett put substantial work into redrawing those effects into English.

From uniquely tailored choice of fonts to hand-drawn text within the art, Bennett's lettering across three localizations of Matsumoto's work is careful, innovative, and has brought a level of quality to manga imports that is still relatively rare.

Because the original effects in Ping Pong are art themselves, Bennett hand-drew English-language substitutes and often found himself drawing in background art to fill the holes created by the absence of the Japanese script. In each case, he worked to put himself into the mindset of Matsumoto, trying to decide how the creator would have drawn a particular PAK or a KYAK or a POK. Method acting for letterers. Bennett describes it as somewhat like forging a signature: “You practice the forms, pushing aside your own tendencies to adopt the other person's hand.”

Ping Pong is also helped by bringing on Michael Arias to translate. Arias, a longtime fan of Matsumoto, directed the film adaptation of an earlier Matsumoto work, Tekkonkinreet, as well as translating two other of Matsumoto's graphic novels, Sunny and Cats of the Louvre. Arias' familiarity with Matsumoto's work, with his narrative pacing and his voice, lends itself to a seamless translation, easy to fall into. Ping Pong, like most sports stories, lays out a series of character studies. Any excitement or inspiration derives not so much from the display of athleticism so much as from seeing these characters grow against the obstacles in their paths, crash against them, and become new creations. Arias' script punches well and keeps us invested throughout.

One Story

by Gipi (translated by Jamie Richards)

128 pages

Published by Fantagraphics

ISBN: 1683963199 (Amazon)

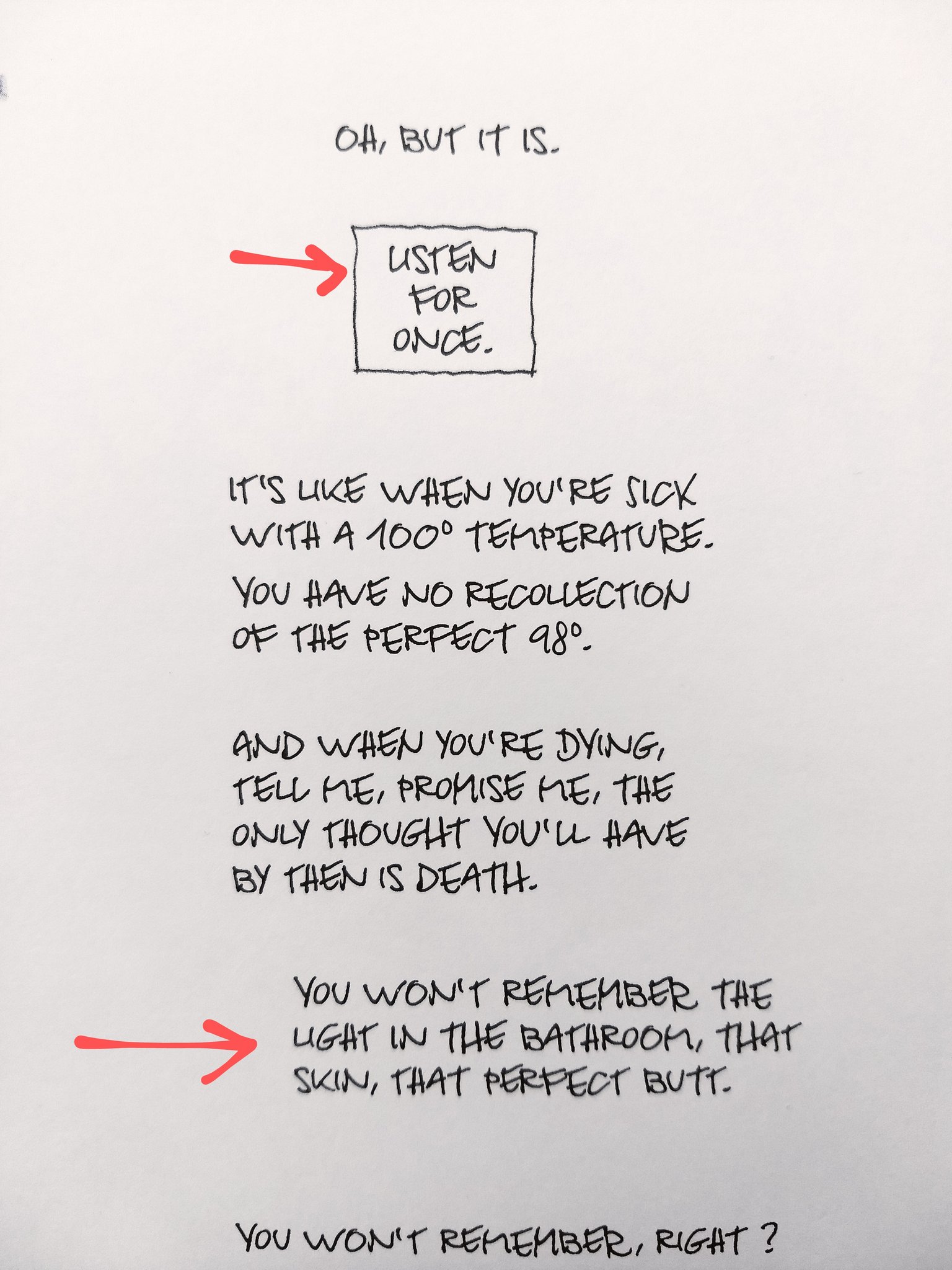

A jaw-droppingly gorgeous story of a celebrity author whose mental deterioration leaves him stranded in his own fabrication of his great grandfather's memories in the trenches of WWI, extrapolated from some discovered letters he fixated on decades ago to the ruin of all else.

My only quibble is the lettering. Any time I follows L, it makes a U. Like so:

"Usten for once." "It's uke when you're sick with a 100į temperature." "You won't remember the ught in the bathroom."

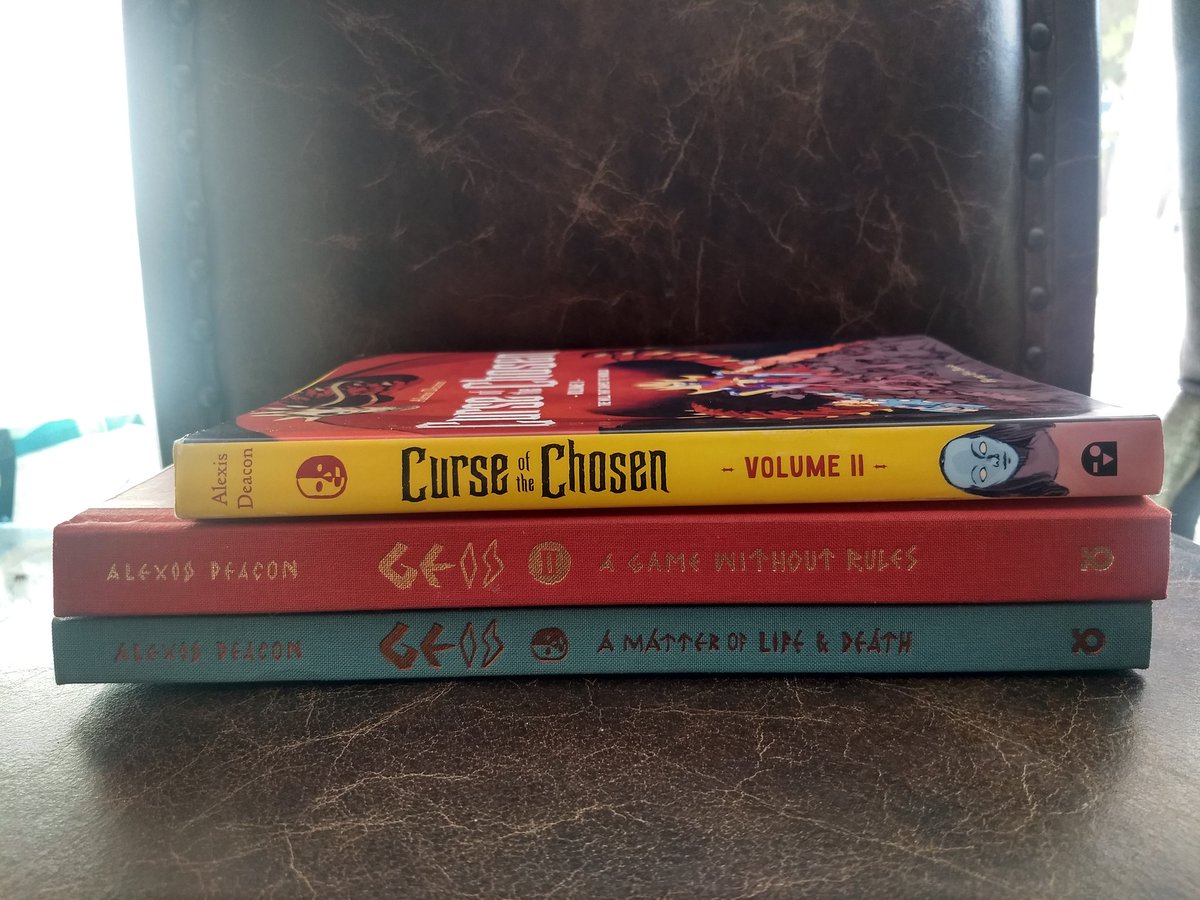

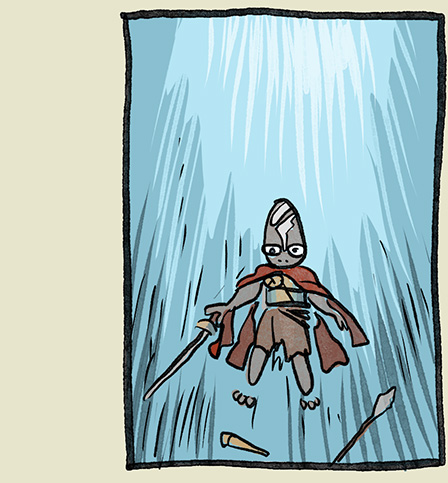

Curse Of The Chosen (formerly Geis)

by Alexis Deacon

2 vols

Published by Flying Eye

ISBN: 1910620831 (Amazon)

Curse Of The Chosen (formerly Geis) just absolutely slaps. It's a dark fantasy series—but not dark fantasy in the overly chatty, grimdark, ironically self-assured manner of we've seen become boringly common today. This is understated and confident without being jabbery. The art is delicate, sometimes feathery with bold colors and strong layouts. Lovely, tricky, sinister work. And smart. Not in the I'm-smart-watch-me-drop-pop-allusions sort of way. Just a really cleverly conceived story that never forgets where it's going or where it came from.

One thing. While vols 1 and 2 were released several years ago in nice hardbacks and beautiful matte paper under the title Geis, vol 3 was delayed and delayed. Finally, it's come out but they've rebranded the series as Curse Of The Chosen. Vols 1 and 2 of Geis are now included in a single vol, Curse Of The Chosen, vol I and Geis, vol 3 is titled Curse Of The Chosen, vol II - so the trilogy is now available packaged in two vols, which is great for new readers. Unfortunately for old readers, the finale is only available in paperback and is smaller at 82% the size of the previous editions. Here's how they'll look on my shelf:

I'm sure this was all related to marketing and maybe Geis wasn't either evocative enough or easy enough to remember. All I know is that bafflingly Geis didn't get anywhere near the play it deserved in the US. This is top-tier fantasy storytelling.

Dead Dead Demon's DeDeDeDe Destruction

by Inio Asano (translated by John Werry, lettered by Annaliese "Ace" Christman)

12 vols

Published by Viz

ISBN: 142159935X (Amazon)

Tweet thread readthrough

In Asano's Dead Dead Demon's Dededede Destruction, he retains the wild cynicism that you'll readily find in his other works but spices it up with some lunatic humor. This is a book about catastrophic alien invasion and how, for the average citizen, that'd merely just be a minor hassle to ignore while continuing to work our ultimately meaningless jobs. It begins as a funny book (and one gorgeously drawn) with Asano continually poking at the bear of contemporary society and its values, but as revelations and reality pile up, it grounds its zaniness in sober reflections and grim consequences.

If you found Goodnight Punpun too brutal (and, I mean, fair point) but still want to take part in the Asano conversation, Dead Dead Demon's is probably your entry point. The final volume (vol 12) is set to land a couple months after I write this and the whole thing is a doozy.

After the parallel world flashback emotional devastation of vol 9, Asano gets us to the moment promised since vol 1, The End Of Humanity, and it's huge. I haven't seen such colossal scenes of concussive destruction since Akira blew his top in the middle of Akira. Asano's technique is completely different from Otomo's but the effect is just as startling.

John Werry pours out a firehose of social chatter in the bookís text, catching the voice and flavor of all of Asanoís tar-gets, whether young or old, liberal or conservative, authority or disenfranchised. His dialogue sparkles and shines in exactly the spastic oversaturated way that Asano clearly intends. Annaliese Christman for his part blows the top off with careful lettering choices that exactly suit the mood of every panel. Text in messaging apps feels like text in messaging apps. News articles look like news articles. Advertisements, magazine covers, news chirons. They all look like they were originally presented in English. The transformation of Japanese sound effects to English is bold and striking, adding weight to the story as it rolls out. Itís breathtaking how much work Werry and Christman put into this localization.

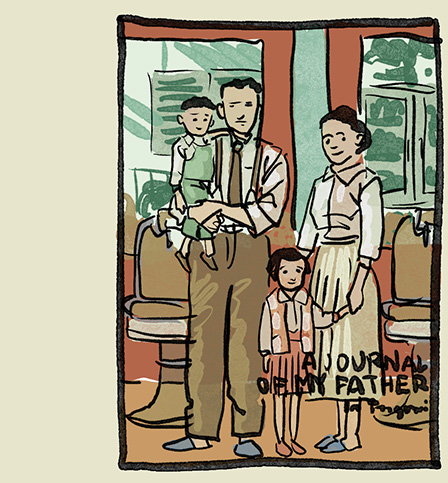

A Journal Of My Father

by Jiro Taniguchi (translated by Kuman Sivasubramanian)

280 pages

Published by Fanfare/Ponent Mon

ISBN: 1912097435 (Amazon)

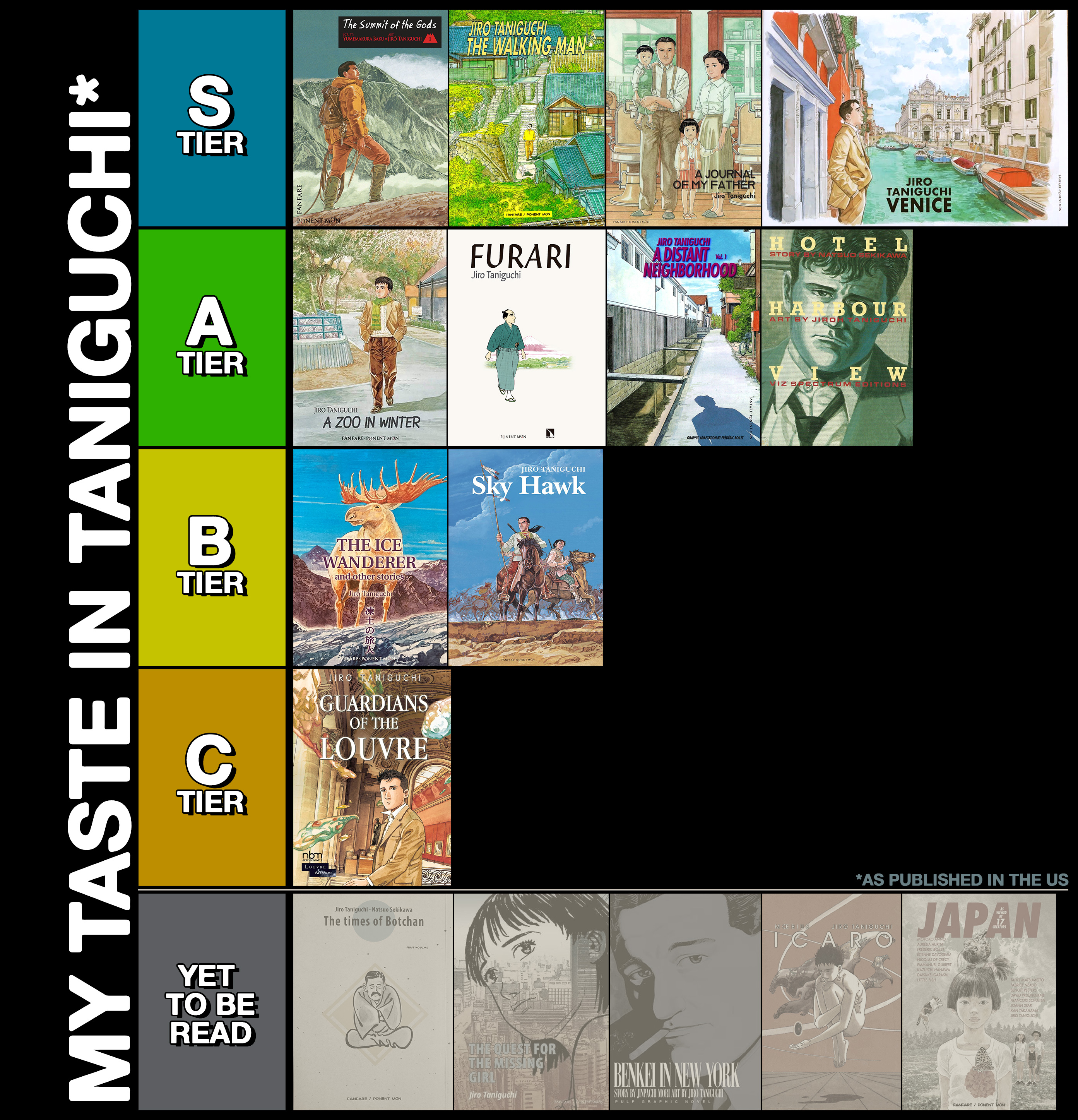

Written roughly in the early middle of Taniguchi's career, Journal follows a man returning for the first time in decades to the town he grew up in to attend his father's wake and funeral, a father he's long had no communication with and whom he bears plenty of ill feeling toward. There he comes to discover through conversations with others the depth of how badly he misunderstood his father and the life they had. It's a thoughtful, insightful look at estrangement and the fallibility of experience. Journal is in my top 3 favorite Taniguchi works, see?

And note: I absolutely recommend this episode of Mangasplaining in with the cast talks through A Journal Of My Father in ways I'm incapable of. It's a delight and peels back some additional personal meaning that will almost certainly add to your own experience of the book.

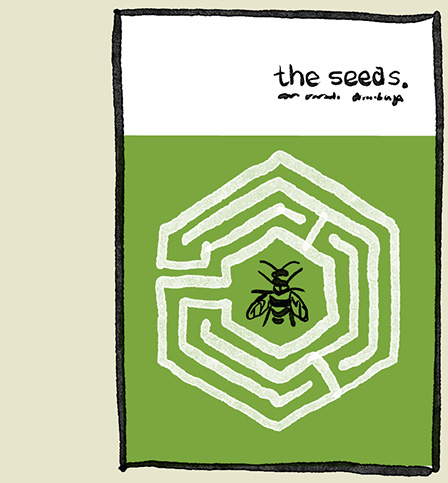

The Seeds

by Ann Nocenti and David Aja

128 pages

Published by Berger Books

ISBN: 150670588X (Amazon)

While Louise Simonson and Chris Claremont were the first comics writers I ever followed, Ann Nocenti was the first to blow me away, to stop me with a Wow. She did stuff I didn't know to think possible with comics. The Seeds was unquestionably a treat, to see her stomping again, free to blow our minds with the able and explosive design and illustration talent of David Aja.

In a broken future, the world is poisoned and divided and there are aliens and seeds and something about... bees. It's all very wacky and Nocenti-esque and recalls some of her wilder flights in Daredevil.

And visually it's a real treat. Aja uses only black, white, and a single toxic bit of yellow-green. No grades, just stark, brutal halftones.

Vattu

by Evan Dahm

4 vols

Read on Rice-Boy.com or purchase from Topatoco

After twelve years, Dahm finally finished his epic political fantasy about a little fluter named Vattu. Dahm is one of the most creative voices in fantasy, refusing as part of his purpose to fall back on stale fantasy races (humans, dwarves, elves, halfings, etc).

It was an incredible piece of storytelling. I've not read anything like it. So surprisingly fresh, constantly hitting me with what I don't expect. So many stories, so many peoples. Absolute joy to have been here for it.

Aposimz

by Tsutomu Nihei (translated by Kumar Sivasubramanian, lettered by Darren Smith)

9 vols

Published by Vertical

ISBN: 1947194305 (Amazon)

Tweet thread readthrough

The art in Aposimz is both wild departure and apotheosis of Nihei's creative vector. It's spare, fragile, airy. A rejection entirely of his ultra-dense, shattered, and much darker (in that his pages were soaked with ink) earlier work. Knights Of Sidonia, Aposimz's closest relative visually, relied on crisp lines and heavy solid blacks early on, but by the final volumes you get what is prototype to Aposimz. In fact, backgrounds in late Sidonia could sit comfortably in Aposimz.

This feels the strongest work and most confident illustration work we've seen from Nihei. I don't have any idea where he'll go from here, if anywhere at all.

Nihei books tend to be these nihilistic deathscapes where life's value is measured only in the collection of moments a background character survives until they get squished by the environment that "supports" them. Life is cheap and vain. In a very real sense in Nihei, life doesn't matter. The moments of comfort readers receive when a character or community avoids extinction is us importing our values onto Nihei's worlds. It's hollow. They survive, but only for the next week - if lucky. There's no real sense that the inhabitants are building toward a living culture. Their only real purpose is survival - for the sake of survival. But the deathscape Always wins.

Knights Of Sidonia, with Nihei attempting to be his most commercial, changes things up a bit and has a hero attempting to preserve a culture under threat. Life is still incredibly cheap in Sidonia, but there's at least some sense of value to the human endeavor. Aposimz is new though. It takes the same old brutal deathscape from Blame or Biomega, but gives us in that penultimate chapter a twist that both explains why life on the surface is vanity *and* how life can have value (both inside and outside the core).

At the end of the day, Aposimz may be my favorite work from Tsutomu Nihei. Apart from some fan-service topos nonsense, which just isn't what I'm looking for in a book, this is super great Nihei.

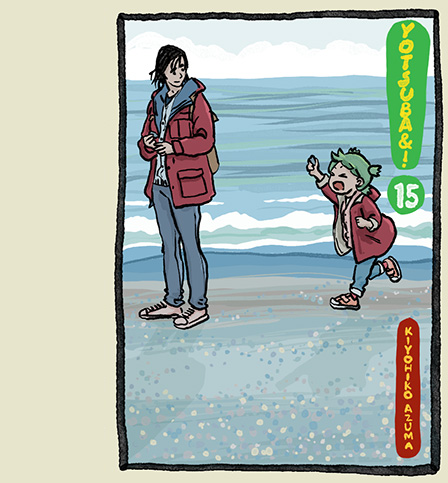

Yotsuba&!

by Kiyohiko Azuma (translated by Stephen Paul, lettered by Abigail Blackman)

15+ vols

Published by Yen Press

ISBN: 1975336097 (Amazon)

I met my wife in 2004 and ever since, whenever a new volume of Yotsuba&! comes out, we curl up together and I read it to her. Vol 15 came out mid-pandemic, so we squirreled away for a bit and I read to her from it. A delightful experience as usual. I'm not sure but it's possible that each book is better than the last. We stop every few pages to point out the moments and expressions we recognize from our own kids. Three of them so far have been Yotsuba's age (4yo) and it's clear Azuma has spent time with kids that age, because he nails it. Yotsuba is exactly as ridiculous as any of our own kids.

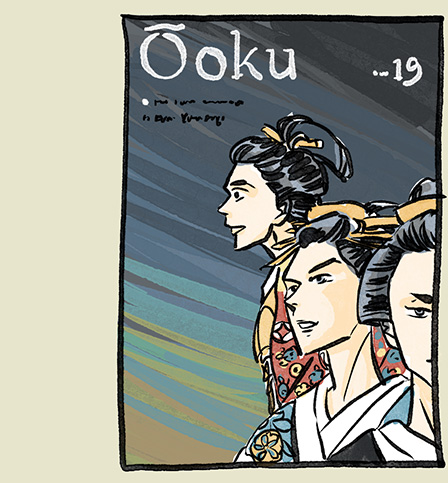

Ooku

by Fumi Yoshinaga (translated by Akemi Wegmuller, lettered by Monalisa De Asis)

19 vols

Published by Viz

ISBN: 1421527472 (Amazon)

Yoshinaga ran this massive project for more than 16 years, retelling the history of the Tokugawa Shogunate as the True-And-Secret-History-That-Had-Been-Lost-To-The-Whims-Of-Fate-And-Patriarchy. And allow me to allay any fears: it is wonderful and ends wonderfully. Just perfect.

19 volumes is a lot for people jumping in. I mean, not for One Piece readers obviously, but for people interested in a gradually paced series of political love stories set against a century-long plague, 19 volumes may be daunting, but it is so well done I don't hesitate to recommend jumping in feet first.

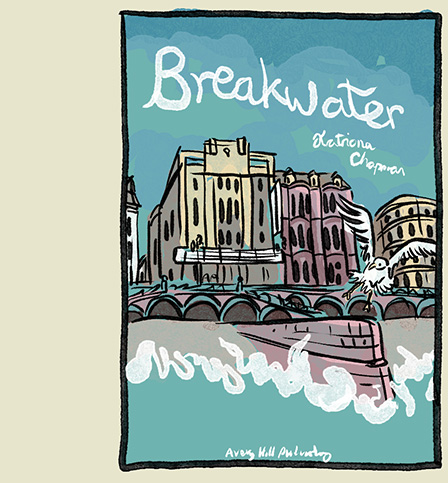

Breakwater

by Katriona Chapman

160 pages

Published by Avery Hill

ISBN: 1910395579 (Amazon)

Holy cats this was good comics. Chapman tells the story of a woman who isn't comfortable around people but makes friends with a really thoughtful and understanding guy WHO HARBORS A DARK SECRET, only it's way more mundane than that sounds. Chapman's characterizations are pitch perfect and the conversations unfold beautifully. It's a great story about being friends with someone who is simultaneously exactly what you need in a great friend and and a life-sucking drain on your emotional resources. Powerful work.

Tuki

by Jeff Smith

2+ vols

Published by Cartoon Books

ISBN: 1888963751 (Amazon)

This is the first third of Smith's latest adventure, taking place in 2 million BCE (give or take a year or two) during a period when several early ancestors of homo sapian co-existed (often violently). This is a beautifully drawn adventure featuring the same lush blacks as Bone. I'm glad I read vols 1 and 2 together because vol 1 alone would have felt probably too slight. Together though, they serve as a great introduction to the mysteries, protagonists, and factions. Just as Bone took ages to spool out, I suspect it'll take years to reach the finale, but just as with Bone, I'm sure the wait will be worth it. Good, fun book.

Always Never

by Jordi Lafebre and Clémence Sapin

152 pages

Published by Dark Horse

ISBN: 1506731376 (Amazon)

Always Never is a tremendous excursion into cartooning in that Lafebre is one of the best character artists around. The book uses an interesting reverse chronological format, not one we've never seen, but still used to good effect. It begins with chapter 20 and counts down to chapter 1. At the book's start, the principle couple are finally going to begin seeing each other romantically in their retirements. The following earlier chapters show us how they got there, bridging a span of 40 years or so. At the book's end, they are around age 18 or so, and meet for the first time. It's a love story that for a lot of its space is a break-up story—and absolutely worth any reader's time.

A Frog In The Fall

by Linnea Sterte

330 pages

Published by Peow

As good as Stages Of Rot is, A Frog In The Fall (Sterte's follow-up with the dearly departed Peow) is even better. Or at least more in line with my tastes. It was such a charming, earthy surprise, with a delightful sense of humor and timing. Story-wise, a young Japanese frog who's never known winter, is lured by the tales of a couple vagrant toads by their plan to head to the sea and find passage to the tropics. It plays out like a road adventure, with a series of pericopes along the way featuring other creatures, a dog, a village of cats, a friendly plum tree. Sterte dresses her characters in rustic pre-Meiji attire and pays careful attention to her illustrations of various flora. It's a beautiful work filled with mystery and longing, forgiveness and hope, and a lot of surprising laughs.

№5

by Taiyo Matsumoto (translated by Michael Arias, lettered by Deron Bennett)

4 vols

Published by Viz

ISBN: 1974720764 (Amazon)

Within Matsumoto's collection of work №5 is kin to Gogo Monster. It's unhinged in that way the vibes you into a new sense of reality. Sure, it says superheroes on the tin, but if Marvel Studios had the balls to put something like this out to multiplex audiences, the world would change. The Snyder cut kiddies would vanish in a Thanos snap and Scorcese would say, "Hell yeah Marvel cinema!"

But since that won't happen, take heart that you can see this vision of the future in 4 beautifully produced volumes of №5.

Plotwise, there's a team of superheroes numbered in order of prowess. They work for/with the government and enjoy massive celebrity. At the opener, the fifth strongest has kidnapped/rescued №1's girl, Matryoshka, and has killed one of the team already in his escape. The rest of the series is a surreal chase full of combats between these super monsters and character building moments that add to the pathos of this grave tragedy.

Save It For Later

by Nate Powell

160 pages

Published by Harry N. Abrams

ISBN: 1419749129 (Amazon)

In Save It For Later, Powell presents several essays on political action for civilians, especially interacting with the question of how he as a parent navigates what he views as civic responsibility and the urgency of teaching his children that compassion for neighbors means action. This is one where I read it long enough ago that the details have largely faded, which just means that I'm due for a reread of a book that surely deserves a reread.

Dai Dark

by Q Hayashida (translated by Daniel Komen, lettered by Phil Christie)

4+ vols

Published by Seven Seas

ISBN: 1648271162 (Amazon)

While I miss Dorohedoro, Q Hayashida's new series is just as madcap and incredible as you'd expect. Really, I don't know what else there is to say. If you liked Dorohedoro but aren't yet buying Dai Dark, you're probably somehow broken inside, because this is exactly what your life needs.

It's Lonely At The Center Of The Earth

by Zoe Thorogood

196 pages

Published by Image

ISBN: 1534323864 (Amazon)

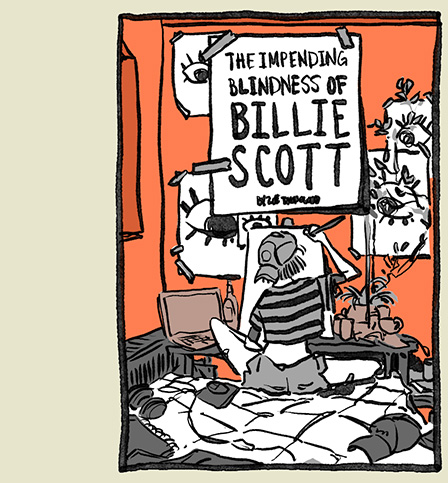

This was so great. Thorogood levels up so much between The Impending Blindness Of Billie Scott and this that I'm kind of beside myself. I'm not remotely a fan of autobio comics, so they always have to work extra hard to win me over. Within pages, I knew that I would love this book. And it helps that the book has a HUGE Chainsaw Man/Look Back/Goodbye, Eri vibe. I don't know how conscious Thorogood is of channeling Fujimoto, but Lonely At The Center looks so good because of it.

In

by Will McPhail

272 pages

Published by Mariner

ISBN: 0358345545 (Amazon)

In is a tremendous feat of cartooning. Some of it may read a bit too twee, but regardless this is a work that should be examined by anyone interested in how comics work. McPhail threads the needle of performance vs authenticity (by now a tired old horse in other media), but does so with verve and imagination. And some of these pages are an unaccounted for pleasure to behold (e.g. the single page depicting the theatricality of the contemporary mating ritual).

The Junction

by Norm Konyu

176 pages

Published by Titan

ISBN: 1787738302 (Amazon)

Konyu's smart little ghosty mystery book had the bad luck to arrive with the pandemic. Absolutely nothing that came out in 2020 got its due, overshadowed by News and by the usually quiet trauma of global fears and lockdowns and waaaaay too much internet.

But guys, this book so good. It's crisply delivered and (despite my usual distaste for vector illustration) looks great.

It won't spoil anything to say that Konyu presents a supernatural mystery—the book opens with 11-year-old Lucas Jones showing up on his uncle's doorstep 12 years after he and his father mysteriously disappeared, and he hasn't aged a day. The breadcrumbs trickle out as the lead detective and the psychiatrist evaluating Lucas pour over the diary Lucas kept while in a town called Kirby Junction.

This is Konyu's first graphic novel, realized first through crowd-funding, and then published in hardcover by Titan in a 2022.

Lupus

by Frederik Peeters (translated by Edward Gauvin)

392 pages

Published by Top Shelf

ISBN: 1603094598 (Amazon)

This in some ways might be Peeters's best work. It concerns a complicated set of human relationships, an expansive and inventive environment to explore, and the kind of dream/vision/hallucination his books are known for. It kind of crosses Blue Pills, Aama, and Pachyderme. I may still prefer Pachyderme, but Lupus feels more robust.

The Harrowing Of Hell

by Evan Dahm

128 pages

Published by Iron Circus

ISBN: 1945820446 (Amazon)

Harrowing Of Hell was beautiful, and I had no idea what to expect. A meek, wounded Christ enters into hell and journeys through, almost ushered to Satan's place there, along the way receiving both reverence and mockery. Dahm's Satan delivers a devastating indictment of what we see in the historical and American church related to Christ's canonical temptation. His words are gorgeous, savage, and still stick with me.

Guyabano Holiday

by panpanya

210 pages

Published by Denpa

ISBN: 1634429648 (Amazon)

panpanya is a gift. Guyabano Holiday is a single volume collection of haunted short stories, investigating our sense of the world through the oblique. Thoroughly mundane until thoroughly not, these are some of the cleverest, most fascinating stories I've read. They're cynical, but not in a negative way. They're skeptical, but not in a way that belies belief. They're richly imagined, they make me laugh, they make me consider. They're really weird but—and this sounds dumb—not really all that weird at all. I think you just have to give yourself up to panpanya's world.

A creator in the vein of Haruki Murakami, panpanya explores the hidden corners of the world, and so itís fitting that Ko Ransom carries a tone throughout the work that seems an echo of Jay Rubin and Phillip Gabriel, Murakamiís own translators. This is especially evident in the ruminating mini-essays panpanya includes between each story. These are delightful excursions into a genre that might just be called thinking-bout-stuff.

Hedra

by Jesse Lonergan

48 pages

Published by Image

Purchase from (Image)

A silent comic with the most gorgeous panel design. The story's a bit simplistic, but that's not the main draw. The reason to read Hedra is to bask in the absolutely fabulous page designs Lonergan devises for the book. He works a 35-panel grid (5x7) and is constantly fiddling and inventing across the book, often breaking the "rules" of comics reading in perfectly lovely ways.

Hedra is so visually fun, in fact, that I almost immediately began incorporating it in the Making Comics afterschool course I teach every year.

The Winter Of The Cartoonist

by Paco Roca (translated by Andrea Rosenberg)

128 pages

Published by 1683963245

ISBN: 1683963245 (Amazon)

With Winter Of The Cartoonist, Paco Roca tells the story of the rise and fall of an independent collective of five legendary cartoonists. Unhappy with the pay and treatment by big 1957 Spanish comics publisher Editorial Bruguera and wanting to kick a little harder against Franco's censors, these five artists quit to form a new comics publication, Tio Vivo. Think of it as Image Comics but 35 years early; and then imagine that Marvel had the power to crush Image within a year by putting pressure on channels of distribution. Imagine Todd MacFarlane, Jim Lee, and Rob Liefeld crawling back to Marvel within a year. That's the story Roca's telling.

And he's telling it because that's the way it happened.

Roca bounces back and forth between 1958 and 1957 so that we know that Tio Vivo failed within the first couple pages. That's the set up. That's the uninteresting part. It's the relationships between editors and artists and publishers that draws the attention. It's the lurking menace of Franco. It's the hope that rests in dreams.

Silver Spoon

by Hiroma Arakawa (translated by Amanda Haley, lettered by Abigail Blackman)

15

Published by Yen Press

ISBN: 0316416193 (Amazon)

I can't even describe just how fun Silver Spoon is. I probably like it more than Full Metal Alchemist. Maybe even a lot more than Full Metal Alchemist.

Arakawa's story about a city boy attending an agricultural highschool finally came to a close in 2020 and we watched him grow from naive failure into someone with goals and dreams and a chance. My kids read this over and over. Maybe they'll even learn something from it, but even if they don't, it's worth it just because of how much joy the book brings.

Dragon Hoops

by Gene Luen Yang (coloured by Lark Pien)

448 pages

Published by First Second

ISBN: 1626720797 (Amazon)

Dragon Hoops is for the reader who loves sports. Dragon Hoops is for the reader who doesn't think sports are that interesting. Dragon Hoops is for the reader who likes human interest stories. Dragon Hoops is for the reader who likes history. Dragon Hoops is for the reader who likes a little behind the scenes comics stuff. Dragon Hoops is for readers who like navel-gazing protagonists. This last one is where I fit in.

Dragon Hoops begins with multiple-award-winning comicker Yang full of self-doubt, wondering how on earth he'll find an idea for his next Big Book. He just happens onto the idea of following the basketball team at the Catholic high school he teaches math at. Along the way, there's lots of wondering what to do, how to approach it, how to balance family, what happens to the book if the team doesn't win, whether he should include the coach accused of molesting boys as part of this feelgood story. There's also the subplot where (shades of Seagle's It's A Bird) he gets offered to write Superman and has to decide Yay or Nay.

It's a good book, surprisingly exciting. Yang takes care to spend time on the team members, to explore the coach's story, to talk about what the school means to him. All of this builds investment and pays off in the end. And, as most of his personal book (e.g. American Born Chinese and Boxers & Saints), there's more going on here than just the surface story of How Did The Team Do?

Goodbye, Eri

by Tatsuki Fujimoto (translated by Amanda Halley, lettered by Snir Aharon)

208 pages

Published by Viz

ISBN: 1974738930 (Amazon)

In Goodbye, Eri, Fujimoto twists narrative through a series of revelations and feints so that by the end, we're never quite sure what "really" happened. The story takes a couple opportunities to poke at curated lives and experiences and how storytelling, which is oppositional to true documentation, might be better after all, lining up with the moral of Yann Martel's Life Of Pi that the better story may actually be the truth's truth.

F

by Imai Arata (translated Ryan Holmberg, lettered by zhuchka & Tim Sun)

224 pages

Published by Glacier Bay

Purchase from (Glacier Bay Books)

Imai Arata's graphic novel is transgressive in repurposing hostages John Cantlie and James Foley, throwing their real-life situations into a post-Fukushima Japanese warzone. It's brutal, poking at the volatility of the imperial powers via the reprehensibility of the terrorists.

The Girl From The Other Side

by Nagame (translated by Adrienne Beck, lettered by Lys Blakeslee)

11 vols

Published by Seven Seas

ISBN: 1626924678 (Amazon)

What a book. The Girl From The Other Side is a beautiful faerytale exploration of grief and love, despair and hope, desolation and consolation.

Doesn't hurt that the art is lovely either.

The Golden Age

by Roxanne Moreil and Cyril Pedrosa (translated by Montana Kane)

2 vols

Published by First Second

ISBN: 1250237947 (Amazon)

Both volumes of The Golden Age feature some of the most incredible illustrations to grace the comics form in, well, its long history. Pedrosa is an unreal creator. And while no story could likely equal the art on these pages, The Golden Age is at least interesting, following a young queen in exile, fighting against her despotic younger brother, all while a democratic movement rises amongst the peasantry—and a rotting curse threatens the life of the good young queen.

Ducks

by Kate Beaton

436 pages

Published by Drawn & Quarterly

ISBN: 1770462899 (Amazon)

Originally a short series of reflections posted in 2014 on her Hark A Vagrant website (coming out to between 27 and 40 pages worth of comics), Beaton's expanding the telling of her time on the oil sands dramatically. I'd described the original as "sad and funny and poignant and altogether human." At 436 pages Ducks, as it is now, as true and whole a Ducks as we will see, is dark. Grim and harrowing for sure, but throw in some other descriptors: heart-breaking, rage-inducing, tragic, awful. There are moments of humor, moments of poignancy, but the whole thing is smothered by the absolute, unquenchable awfulness of men when they are not at home.

While Beatonís earlier attempt at telling stories from the Albertan oil sands (she worked for Syncrude and Shell) focused on the inhumanity of the work, the environmental impact of the oil extraction process, and the essential humanity of the workers cut off from their homes and families, in the present telling, Beaton tells more of the whole story, and that is a story of how a project focused on stripping resources from the land as efficiently as possible unsurprisingly also builds a world steeped in misogyny, sexual objectification, harassment, assault, and rape. As a result, many of the things that felt central to Ducks (2014) fade into the background of Ducks (2022). Beaton still includes most of the stories she used in the earlier Ducks, but the horror of asshole men is so exhaustingly pervasive that it dominates the book.

And thatís not a criticism. As young Beaton asks, what good would Ducks be if it elided the most everyday and constant of Beatonís experiences on the oil sands? Ducks (2014) reminds us gently of the human cost of industry. Ducks (2022) will not allow us to forget the human cost of industry. Itís like Grave Of The Fireflies like that.

Beaton juggles a lot here, thematicallyóand most of it successfully. Ducks is good. Ducks is even probably great. I don't know how soon I'll reread it or if I'll ever reread it. It just makes me mad.

It did, however, inspire me to write my first real review of a book in more than a year—so there's that!

Meadowlark

by Greg Ruth and Ethan Hawke

256 pages

Published by Grand Central

ISBN: 1538714574 (Amazon)

Meadowlark is so good. Only reason I can think of that it's not talked up, like, at all is that it landed during the pandemic. I guess? Tail end of it so who knows. But nobody was talking about it in their year-end lists and that's just insane.

Meadowlark is Greg Ruth and Ethan Hawke telling a story about fathers and sons and how hard it can be to be either of those. All told atop a gruesome prison escape story. I don't know if Ruth and Hawke have more in the pipe (this is their second after Indeh), but I'll be here for it if they do.

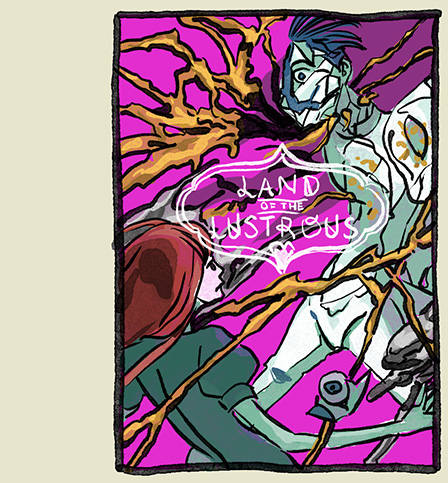

Land Of The Lustrous

by Haruko Ichikawa (translated by Alethea Nibley and Athena Nibley, lettered by Evan Hayden)

12+ vols

Published by Kodansha

ISBN: 1632364972 (Amazon)

SYNOPSIS: The world is very different than it was. There are, essentially, three forms of life: the mollusks, the Lunarians, and the gemstones. And Sensei, whatever he is. The Lunarians attack the gemstones fairly regularly for reasons unknown. The gemstones are smartly dressed creatures (coded as vaguely androgynous women) whose toughness and character is related to the Mohs scale of the gem from which they're formed. Most of them are hundreds of years old. This story concerns Phosphophyllite, a fragile and pretty useless gem, as it investigates the world and seeks to understand the Lunarians and the Sensei.

Land Of The Lustrous is kind of amazing in how rapidly a story about incalcitrant, functionally immortal beings evolves and changes. Some of these characters are 700 years old and harder than steel, but the youngest of their group breaks and remolds and grows and shifts in both form and personality and motivation. She doesn't just have a character arc; it's more like a character squiggle.

And the story continues to evolve dramatically. It's impossible to predict what's going to happen next. I mean, sure, one might expect a manga time skip here and there, but one that's more than 100 years and is the one time the story doesn't principally change? Didn't see that coming.

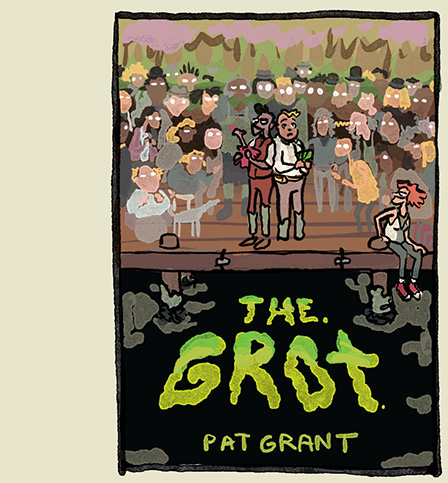

The Grot: The Story of the Swamp City Grifters

by Pat Grant and Fiona McCabe

200 pages

Published by Top Shelf

ISBN: 1603094660 (Amazon)

It's been a while since Blue or Toormina Video were released and I'd been wondering what Pat Grant was up to. The Grot is it and I'm pretty impressed. It's a delightfully grimy story about cons.

In The Grot, the world's gone down the bowl and things like fuel seem a distant memory. Cars and ships run on pedal power and there's been huge speculator boom in the Swamp. Patches of a glowing green substance (grot) have been discovered and Everyone who wants a better life has left for the Swamp to do a bit of prospecting. It's all about as sanitary as you would expect of a place called the Swamp.

It's an ugly place full of ugly people. Grant's work takes on a distinctly misanthropic tone. This may be veneer because the story and characters are simultaneously buoyed by empathy and hope. These people are ugly and terrible and selfish BUT they are propelled by dreams and desires that we can probably all smell in our own motivations.

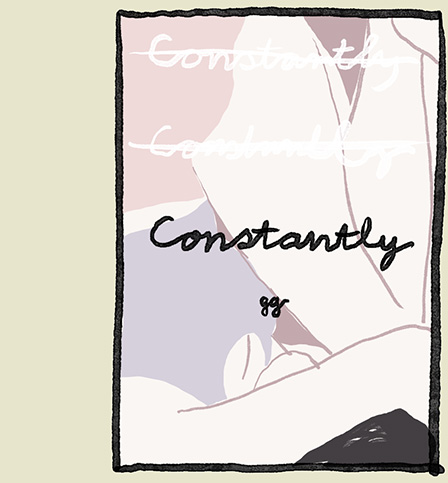

Constantly

by gg

48 pages

Published by Koyama

ISBN: 1927668727 (Amazon)

Call it depression or malaise or even a haunting, but some of us are trapped by unseen hands, by a force that actively prevents us from functioning as we probably ought. They steal from us our desires. The rob us of our motivations. They seem invested in cruelly making every mundane everything just a little more difficult than it should be. A thousand tiny cuts, a thousand light bruises. On their own, they would be nothings, but they come in every moment. Constantly. And their loyalty to their cause, their brute constancy prove able to undo the best of us with relative ease.

Taking the reader through a single morning in the life of a woman from about 5:30 to 9am, gg's Constantly is a slight work. 48 pages and its only words are those written on pages of a notepad that intersperse through the story. You can read the entire thing in bare minutes. Just like you can look at Van Gogh's Starry Night for just 15 seconds if you want. Or 5. The appreciator's time of investment will vary, largely depending on their investment in appreciation.

Constantly is a narrative, but its also somewhat less a narrative than it is a work of art, a presentation of a mood, the revelation of a mode of existence. It may not be for you but it may be just exactly what you need. In any case, her illustrations are lovely as expected.

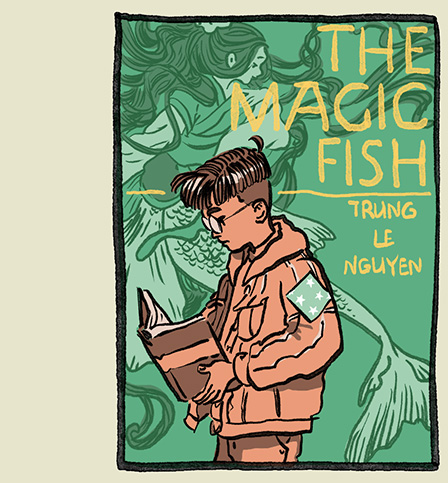

The Magic Fish

by Trung Le Nguyen

256 pages

Published by Random House

ISBN: 0593125290 (Amazon)

Trung Le Nguyen draws the most gorgeous hair. It's unbelievable. In lesser hands his thick, defined strands would look like Raggedy Anne's yarn hair, but through whatever talent/craft/witchcraft, it instead calls out its own lushness. I will never get tired of looking at the hair in The Magic Fish.

The story itself is a lot of fun, a series of faery tales read to a mother attempting to learn better English, the reading of which is broken up by the interruption of daily living. It's a wonderful book about family and loving family.

But, man, that hair.

Two Stories

by Joshua Kemble

1+ vols

Published by Markosia

ISBN: 1913802205 (Amazon)

Kemble won a Xeric a million years ago and embarked on Two Stories, about his attempt at rational suicide, move toward atheism from a dippy Christianity. The upcoming volume is about some brutal assaults, his mental breakdown, and the start of his move back to Christianity. It's very good and pretty grim.

Look Back

by Tatsuki Fujimoto (translated by Amanda Haley, lettered by Snir Aharon)

144 pages

Published by Viz

ISBN: 1974734641 (Amazon)

Look Back, Fujimoto's reaction to the Kyoto Animation attack, is both touching remembrance and meditation on envy as a motivator of artistic growth. It's also about how insecurity feeds competition and how sometimes that can create relationship. Look Back rather came out of nowhere and it has some of Fujimoto's most mature storytelling to date.

Witches

by Daisuke Igarashi (translated by Katheryn Henzler, lettered by Aidan Clarke)

392 pages

Published by Seven Seas

ISBN: 1648278396 (Amazon)

Witches is a one-vol omnibus collecting Igarashi's short series and it's pretty solid (even if they didn't have the budget to tackle the color pages). This was a day-one purchase for me since I'm kind of a huge Igarashi fan and a friend lettered the new translation and poured a ton of work into it.

It's good! We get more of Igarashi's affection for the natural world and the focus on witches across the world allows him to do the kinds of wild earthly/cosmic scenes that made Children Of The Sea so bonkers. This won't lodge in my consciousness like COTS did, but it's solid work and I'm glad to have gotten to read it in English (I have a bunch of pages from it in my Igarashi artbook, but I don't read Japanese, so until now, they've just been art to look at).

Methods Of Dyeing

by B. Mure

92 pages

Published by Avery Hill

ISBN: 1910395625 (Amazon)

Methods Of Dyeing is B. Mure's fourth book in the Ismyre collection and continues the delirious mix of politics, intrigue, murder, and botany. It is always a pleasure to return to these books, not just becuase the stories are fun (as fun as death and danger can be!) but for the wonderfully lush kaleidoscopic tapestry of colors B. Mure invests in every page. Absolutely delightful.

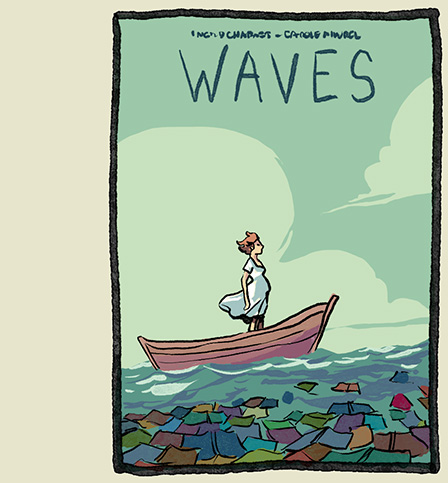

Waves

by Ingrid Chabbert and Carole Maurel (translated by Edward Gauvin)

96 pages

Published by Archaia

ISBN: 1684153468 (Amazon)

Struggled with this beautifully formed novella. Having a hard time dealing with mortality recently. No near losses wreaking their havoc, just anger at the specter of endings, rage at the impotence of life and how frail our dreams are. I didn't realize just how much grief I was still holding over the loss of our middle child until I read Waves. It's been 6 years and most days go by where I only spare a thought or two and quickly (even blithely) move on. But the day I read this completely washed me. Heartbreaking story whose hopeful, healing arc doesn't ever overcome the tragic horror it opens with - which is how it should be.

[Note: it wasn't 'til after I wrote this that I realized that this was a 2019 book, but the work involved in reordering everything is just... well it's a lot. Just pretend that your favorite book I didn't include is sitting here instead. Was there a Saga book in the last few years? You love Saga. It's right here, in spot 44! Congrats!]

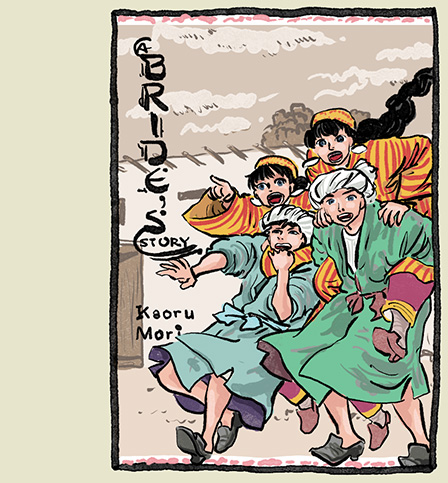

A Bride's Story

by Kaoru Mori (translated by William Flannagan, lettered by Abigail Blackman)

12+ vols

Published by Yen Press

ISBN: 0316180998 (Amazon)

Tweet thread readthrough

With volume 12 we have Smith and company returning to the Aral region even as the political situation grows more and more difficult. We reunite with characters from prior volumes, the sworn sisters and the twins of the sea. With things heating up with Russia, I wonder how much longer Mori will continue the story. I just want a happily ever after for Amir and Karluk.

Stages Of Rot

by Linnea Sterte

168 pages

Published by Peow

Purchase from Stuart Ng Books

This was my second read, the first was in digital but digital sucks, so it was almost like a first read. One of the amazing things about whales is that when they die, their corpses become tremendous seedbeds for new ecosystems. Sterte takes this concept and ramps it up apocalyptically, science fictionally, and fantastically. It's a brilliant work with each chapter sitting in a different stage of the ecosystem's development. It's light on plot but heavy on mood and presence.

Delicious In Dungeon

by Ryoko Kui (translated by Taylor Engel, lettered by Abigail Blackman)

11+ vols

Published by Yen Press

ISBN: 0316471852 (Amazon)

Comedy is hard, but translating comedy and bringing it over to a-whole-nother culture with different puns, different idioms, and different cultural boundaries for humor is harder. Much harder, actually. That Delicious In Dungeon page after page brings laughs and mirth and good feeling volume after volume is incredible. Never a false note, never a joke that fails to land. Ryoko Kuiís book about Dungeons & Dragons-style adventurers stuck in a dungeon, forced to subsist on the monsters they kill along the way is wildly entertaining thanks to Taylor Engelís beautiful script.

Delicious In Dungeon isnít even primarily a humor book. Itís funny, sure, but itís also exciting, mysterious, adventurous, and an exhibition of as creative a world-builder as any working in the fantasy genre today.

The setup feels too simple. A group of adventurers is working to clear out a dungeon full of monsters, discover treasure, and find riches and rewards for their labor. With a bit of bad luck, one of their members is eaten by a dragon while they are teleported to the surface. The leader insists on returning immediately (without taking time to reprovision) to find the dragon, dispatch it, and recover the body before she (his sister) is digested so they can resurrect her (a normal function of dungeon adventuring). Without fresh supplies, they will have to eat the monsters they kill. What rolls out looks like it will follow the conventions of the cooking comic genre, with lots of images of food prep, cooking, delicious looking meals, and satisfied gastronomes ó only with meals like hippogryph tempura or walking mushroom hotpot. While this would get old relatively fast, Kui builds in several compelling mysteries to be picked at as the adventurers travel deeper into the dungeonís ecosystem.

Engelís work is excellent whether in drawing laughs, in conversationally situating characters and their relationships, or in conveying the lore and world-building that Kui very thoughtfully has laid out.

Witch Hat Atelier

by Kamome Shirahama (translated by Stephen Kohler, lettered by Lys Blakeslee)

10+ vols

Published by Kodansha

ISBN: 163236770X (Amazon)

The art of Witch Hat Atelier is stunning. It looks almost exactly as if Arthur Adams followed The New Mutants: Special Edition #1 by tempering himself and taking his structural cues from manga instead of diving deep into whatever it was that turned him into whatever it is that can churn out bizarre thigh after bizarre thigh. The linework and detail is stunning, and the pages are filled with so much exuberance.

I'm loath to say it, but my interest in the series wanes slightly as more and more new characters are introduced. I can only keep so many in my head!

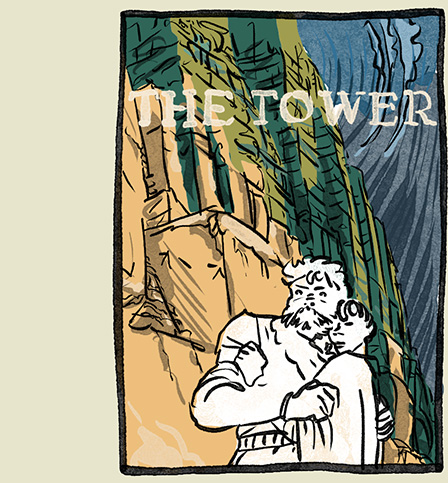

Obscure Cities

by Benoit Peeters and Francois Schuiten (translated by Stephen D. Smith, lettered by Amauri Osorio and Neil Uyetake

7+ vols

Published by IDW

ISBN: 1684057310 (Amazon)

The last couple years have been a great time for Obscure Cities in the US, seeing the release of 4 separate volumes in the collection: Shadow Of A Man, The Tower, The Fever In Urbicande, and The Invisible Frontier. These were pretty much exactly what you expect from an Obscure Cities book that isn't Leaning Girl: incredible art, a wonderfully weird story conceit, everything going wrong somehow, and even repellent dudes scoring with pretty ladies. (The Leaning Girl had all that but also had a layer of thoughtful meta-value on top of all that, making it the superlative Obscure Cities so far.)

My favorite of this new crop was The Tower, which stars a protagonist designed to look like late-middle-aged Orson Welles.

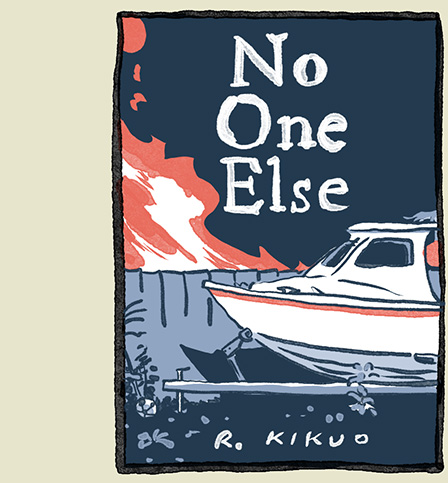

No One Else

by R. Kikuo Johnson

104 pages

Published by Fantagraphics

ISBN: 1683964799 (Amazon)

D'you want more Jimmy Corrigans? Because this is how you get more Jimmy Corrigans.

It's always tough to read stories about parents incapable of showing love, incapable of relating to other people in ways that don't create distance. It's tough on themselves for sure, but more, by their distance and disassociation they're creating fresh people to grow up broken and bent in ways either like or tangential to their own brokenness.

No One Else is that kind of story. We see a man die from the careless negligence of his grandchild (but kids are whimsical and careless negligence is part of their ethos) and then we see the effect of his death on his grown children and it's... disheartening. No One Else exists as a long held breath, and even in the end when the sigh comes, it's a hesitant, struggled thing.

I had been looking forward to seeing more of the lush brushwork and inventive illustrated collage we saw in The Night Fisher, but in the intervening years, Johnson seems to have pared back to a simpler, cleaner style. It looks good. Sometimes it looks real good. Here he uses tones of blue with bits of orange to emphasize.

Odessa

by Jonathan Hill

328 pages

Published by Oni

ISBN: 1620107899 (Amazon)

Odessa is a great post-apoc family drama, even if I want to throw the main character into a lake. Maybe because I want to throw the main character into a lake. She's 17 years old, so it's a bit expected, but she's dumb enough (or naive enough) and brandishing that particular kind of selfishness/self-confidence/self-righteousness that the young are galvanized by (I know I was!)—and that gets innocent people killed. It's a first volume with more to come, which caught me off-guard since I didn't see that when I started the book, but it ends in a decent place where everything is nuts but will also be kind of satisfying if it doesn't sell well enough to get a second volume. But man, I'd like to see a second volume, because it ended with everything kind of nuts.

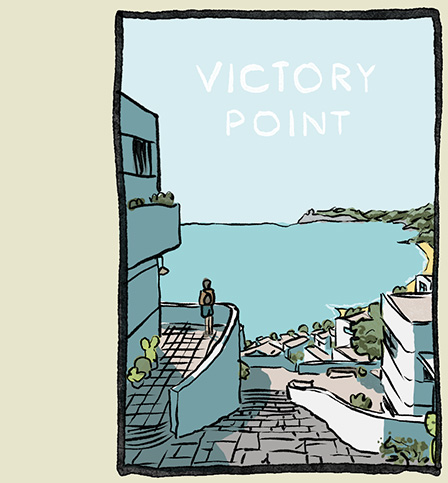

Victory Point

by Owen D. Pomery

80 pages

Published by Avery Hill

ISBN: 1910395528 (Amazon)

In Victory Point, Owen D. Pomfrey allows us to explore a meticulously rendered and slightly worn architectural marvel of modern design (named Victory Point). The town, 90 years old and never completed, is a beautiful place: a destination for students of architecture but "merely" home to its residents - an example how we can value and make a place for ourselves even in the midst of a failure to achieve purpose. And how maybe that can even be enough.

Ellen Small's life reflects and is reflected by Victory Point. She escaped the experimental town a decade ago but arrives on a visit to her father, who remains. Much of the short book is spent on Ellen wandering the streets and vistas she grew up with, both alienated and alienating. She feels uncomfortable in this place pregnant with depth and meaning, its streets a reminder and her old classmates and albatross. Simultaneously, there are charms that bring back nostalgia and sentiment.

Like most things, Victory Point isn't a singularity. It exists as this, as that, and as other things. To Ellen. To her father. To the people she meets along the way.

Victory Point is a quiet book. There is dialogue, conversation. But these words exist as punctuations to the observation of humanity's effort to mark nature. Nature takes and takes, but Victory Point is at least one man's intention to harness a piece of the world, to carve out a better world for humanity, even if a smaller world. From the beginning, Ellen rejects that world by living away in the city, where the architecture is less a subjugation of nature and more an obliteration of it. Victory Point (the book) is about the pull and draw of Victory Point (the town) and the question of whether the words it whispers can tempt Ellen.

Women's Work

by Caitlin Cass

82 pages

Self-published

Purchase from Cass' store

Cass uses the wit she's honed in more than a decade of Great Moments In Western Civilization to tell the story of the suffrage movements that brought women the right to vote. It's a wry book, pitting heroic strides by various women against walls of patronizing presumption (walls often erected by other women). Her heroes are sometimes heroes but rarely paragons, because they are real people, and Cass doesn't let the reader forget the foibles that went along for the ride. She also doesn't let us forget that despite there being some interest with some suffragists to expand these rights universally, at the end of the day, when it came down to white women voting or no women voting, the suffragists took white women voting. Cass pokes while celebrating, something an old cynic like me just pretty much loves.

Angola Janga

by Marcelo DíSalete (translated by Andrea Rosenberg)

432 pages

Published by Fantagraphics

ISBN: 1683961919 (Amazon)

Angola Jangaís translator, Andrea Rosenberg, has spoken of the ethical dilemma of translation, a quandary that goes beyond any political questions that arise in a text. She acknowledges the fabrication that must occur when a translator overwrites the words of an author (an operation intrinsic to every translation), but she notes that to the reader, fidelity to the author often merely hinges on the question of readability, of fluidity. To the reader, a good translation is one that ceases to be conceived of as a translation, one in which the mechanics of story vanish into the experience of the book.

Angola Janga is historical fiction exploring the final days of the communities of runaway Angolan slaves in the forests of Brazil, following the life of Antônio Soares, a figure mentioned only once within the historical record, a man of ignominy. Brazil between 1500 and 1900 accepted 5.6 million African slaves, nearly 12 times as many as North America did in its own slavery period. In the latter half of the 17th century, escaped slaves formed communities in the jungle to protect themselves from slave-hunting parties and Portuguese soldiers. The collection of these communities was known as Angola Janga. Marcelo DíSalete has been particularly interested in these stories. In 2014, he wrote a collection of short stories published in the US as Run For It (2017), and in 2017 he created the far more expansive Angola Janga.

Rosenbergís translation is interesting because she leaves words from under the Bantu umbrella alone (as DíSalete must have as well), delivering a text in plain English but also filled with non-English terms from either Kikongo, Kimbundu, or the large Bantu linguistic family. While an alienating choice (requiring either simple acquiescence or continued reference to the helpful glossary appending the book), it in a very real way strengthens readersí experience of peoples catastrophically alienated from each other, on the one side by standing victim to inhuman atrocities, and on the other fear, hatred, and a monstrous sense of self importance.

Monsters

by Barry Windsor-Smith

380 pages

Published by Fantagraphics

ISBN: 1683964152 (Amazon)

Monsters has some of my favorite lettering of all time. Not throughout, just in this very specific place, early in the book, when we see a father unhinged and shouting, ranting, in a feral German at or around the son he's beating. Each letter is large, intruding on its neighbors, expanding violently beyond the bounds of the word balloon and being cropped by it. It's a tough scene and the lettering here is as close to perfect as I've seen.

The book took me several tries before I could read it through. It's a strange mix of corny comics writing from the '80s or earlier combined with a devastating portrait of a family living under the terror cloud of a soldier come home from the war and traumatized by something beyond mere shellshock (or maybe he always had this monster lurking within himself). Watching the family tragedy was too much for me on several occasions and I had to abandon my reading to return months later and start anew. It doesn't help that we roughly know where it all is going to end, i.e. Nowhere Good.

Finally though, I did read through Monsters. The art is usually wonderful and the decision to leave it uncolored is a blessing. The story is sprawling, moving back and forth through time at will, and is ultimately I think pretty satisfying. I don't want to read it again (as a father deeply in love with all my children, large portions of the story are just too raw), but it's good to see more BWS art in the world.

Salamandre

by I.N.J. Culbard

152 pages

Published by Berger Books

ISBN: 150673152X (Amazon)

It's nice to see Culbard return to a sole creator credit. (The last time was 2014's Celeste, which was definitely worthwhile and you should hunt it down.) Salamandre is a good ride and kind of, I suppose, a middle grade sort of story (BECAUSE THE MAIN CHARACTER IS LIKE 12 AND THAT'S ALL IT TAKES RIGHT?) about a kid whose dad dies in a submersible accident prompted by greedy owners who skimped on his safety. The kid, not dealing well with things (obv), gets sent across the Iron Veil (an Iron Curtain stand-in) from the Republic of Montparnasse to live for the summer with his grandpa in the empire of Monolith. There's a lot of veiled danger, spies, propaganda, ministry officials, an underground, AND SECRET ARTISTS! It's a fun book and I'm glad to have spent the time in it.

The Con Artists

by Luke Healy

128 pages

Published by Drawn & Quarterly

ISBN: 1770466231 (Amazon)

In The Con Artists, Luke Healy blurs fiction with autobio via a thin disguise—Healy's author-avatar literally dons a fake moustache in the opening so that we won't confuse this for being at all about Luke Healy (wink-wink). The book sits well as a companion to Katriona Chapman's Breakwater, thematically tied through both works exploring friendship with a person who abuses the boundaries of relationship.

The Con Artists is funny, with Healy often mugging in any given page's final panel, as if we were reading a comic strip in need of a punchline. Because of the blur of reality and fabrication, the humor sits uncomfortably and does so intentionally, reminding us of the plurality of Artists in the title and whispering, Hey, there's more that one con artist in this book and you should think about that, 'kay?

Frieren

by Kanehito Yamada and Tsukasa Abe (translated by Misa "Japanese Ammo," lettered Annaliese Christman)

7+ vols

Published by Viz

ISBN: 1974725766 (Amazon)

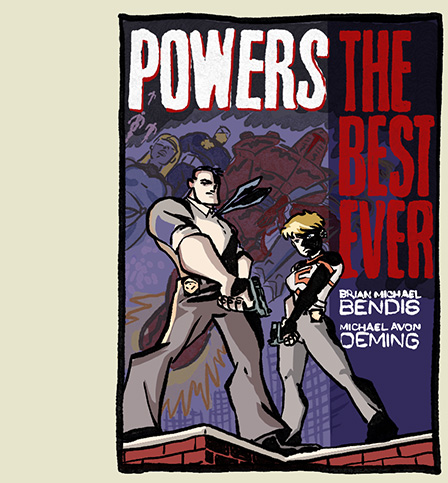

This feels like a cross between Delicious In Dungeon (picking up from the conversation there about age and racial lifespans) and To Your Eternity. It's about an impossibly old elf mage and how she gradually loses all her friends to their own mortal lifespans over and over. In that sense it's also like Bendis/Oeming's Powers except that the mage, Frieren, remembers everything. It starts out nice and breezy but the story is gradually building.

It's a fun series, different from a lot of what's out there. My only quibble is that it may be stretching itself out too long. It feels like it would have been a good 6-volume series, like Girls' Last Tour.

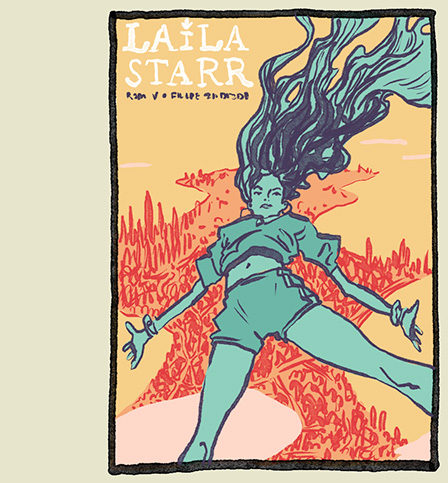

The Many Deaths Of Laila Starr

by Ram V, Filipe Andrade, Inês Amaro, and AndWorld Design

128 pages

Published by Boom

ISBN: 1684158052 (Amazon)

This was the wrong choice for me. It's very well done and engaging, in the thematic vicinity of Daytripper. It's a good book, maybe even a great book, but its ultimate conclusion on the value of death, of dying, ran smack into my last few months of anger about the fact of death and what a damned thief it is. It's thoughtful and does the beauty-in-all-things thing, which... rings a bit hollow. I'm sure this is a helpful interaction with mortality for a lot of people, but it was the wrong thing for me to read at this moment and I couldn't help getting a little pissed off. Good book though with an intriguing concept nonetheless.

Stand Still Stay Silent

by Minna Sundberg

4 vols

Published by Hiveworks

Purchase from Hivemill

I wasn't quite sure what to do with Stand Still Stay Silent. In the period covered, we have both the print edition collecting volume 3 of the first series and the completion of the second series online. Series 1 deserves to be in the top 25 easy. It's one of the best comics I've read. The second story shows potential but never quite gets there and then in the back third just loses steam altogether. Story, writing, and art grow careless, as if Sundberg were going through the motions, just doing it to get it done. After it finished, I realized that this was probably the case. She converted to Christianity partway through the second SSSS story and while not disavowing it entirely, she does say she didn't want to be spending time in that world anymore. And I think it shows. I'm glad for her religious convictions but I'm sad she didn't find her way into one of the interpretations of Christianity that made room for something like SSSS.

Ironically, one of the best instances of a Christian minister in comics is something she created while still an atheist, the pastor's ghost that Reynir meets in the climax of SSSS series 1.

Anyway, Stand Still Stay Silent gets placed here, bumped up for the wonder of volume 3, but bumped down for the collapse of series 2.

SupportNear MissesNavel Gazing

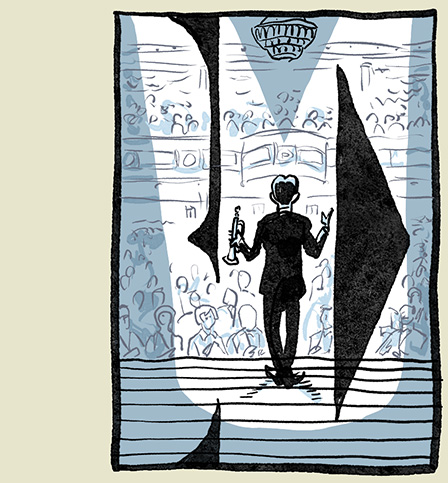

Bix

by Scott Chantler

256 pages

Published by Gallery 13

ISBN: 1501190784 (Amazon)

Bix is Scott Chantler's nearly wordless but nonetheless lyrical telling of the life of jazzman Bix Biederbecke. We chart the path of Biederbecke's life from young musical prodigy in a fundamentally religious home to a young man entranced by jazz music to teen runaway with musical dreams to burgeoning alcoholic to straining to settle down to dissolute wreck. Biederbecke burnt brightly and chaotically. His story pre-echoes many of the jazz and rock luminaries who would follow him. Charlie Parker, Billie Holiday, Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, Bill Evans, Stan Getz, Wynton Kelly, Zoot Sims, Art Pepper. So many casualties from the hard-living that so often accompanied jazz performance and the after-hours environments that ruled the communities.

Chantler's telling of Biederbecke's life is understandably elegiac. Many readers will already know Biederbecke's fate (spoiler, he died in 1931 at age 28), so in some sense we read waiting to see how Chantler will handle what we know is coming. We see the early signs, the foreshadowing. It's downbeat waiting for inevitable mortality to assert itself like this.

But simultaneously, the jazz scene in the Roaring '20s was raucous and filled with frenetic energy, and Chantler conveys that as well. Dancing, drinking, all-night jam sessions, hanging with Louis Armstrong, getting on the wrong train and passing out drunk. The '20s.

Chantler's Bix is formally inventive, generally sticking to a single row of 5 panels at 40% of the page height. His trick is to evoke music by slightly (or sometimes dramatically) raising or lowering panels based on things like mood, energy, punctuation. And then to really punch up scenes, Chantler will throw in a cacophony of panels, many times overlapping, stepping on, and continuing other panels.

Additionally, and Chantler may be taking the cue from one of his epigraphs ("Mute, to a degree, he would always be; verbal communication would never be his medium") in that only 17 out of 254 pages contain any dialogue at all. All communication in the book is nonverbal, told through images alone. And all of this works very well. My only hesitation is that, as a comics reader, I often rely on words to slow me down, to press me to linger on pages. My hunger in stories (at least at first) is to get to the end, to see the thing finished. I'm like this in novels, films, and television. I just want to know what happens. Only then, can I go back and better attend matters of craft. With this in mind, my first read of Bix took me maybe 10 minutes - which is grossly unfair to Chantler and the years he poured into the book. Fortunately, later reads took much longer, and I was better able to admire what was on the page. How Chantler could convey boredom, excitement, worry, disgust, affection, and frustration.

Bix is a worthy project and Biederbecke is one of those early gifted musicians who doesn't necessarily get their due. Later more dynamic talents used more popular and more avant garde modes of the jazz form and became the legends that are more readily recognized by the citizen on the street. Armstrong, Parker, Monk, Gillespie, Goodman, Coltrane, Davis, Brubeck, Getz, etc. And if Chantler's book can get someone to look up some Biederbecke, then fantastic!

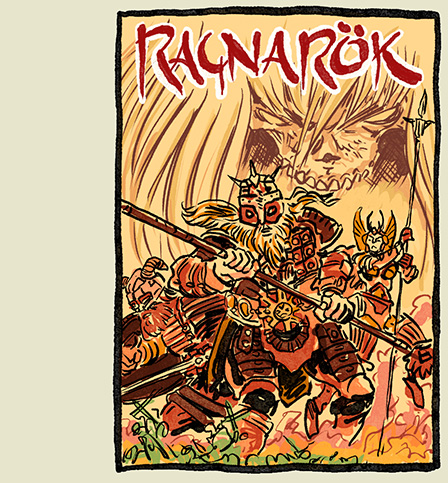

Ragnarok

by Walt Simonson, Laura Martin, and John Workman

3+ vols

Published by IDW

ISBN: 1631400681 (Amazon)

This is a fantastic series that recalls (nostalgia!) Simonson's exemplarary work on Thor from the '80s. It's raucous and celebratory and dour and funny. The concept is basically, what if Ragnarok happened but Thor was chained up and so missed it. He's now a draugr, a term you'll recognize from Skyrim probably, if not from elsewhere. He's awakened hundreds of years after when he was supposed to have his fateful combat with Jormungandr and wanders out into a post-apocalyptic (post-ragnorokic) world in which all the great enemies were stunningly victorious over the gods of Asgard. So he wants revenge. It's a lot of fun and comparisons to the old Marvel book are going to be obvious. I'm not sure if this is Simonson's best work. It might be or it might not, but it's very good. The one thing I'd wish for if I had a wishing panther is for a non-contemporary coloring style. For 1) Simonson's art looks sooo good with brash coloring that the contemporary affection for gradients drains a bit of life from the work, and 2) with both Simonson and Workman on Ragnarok, it feels a bit like getting the team back together, so why not bring back Christie Scheele? (Or at least try to find someone who could color like she used to.)

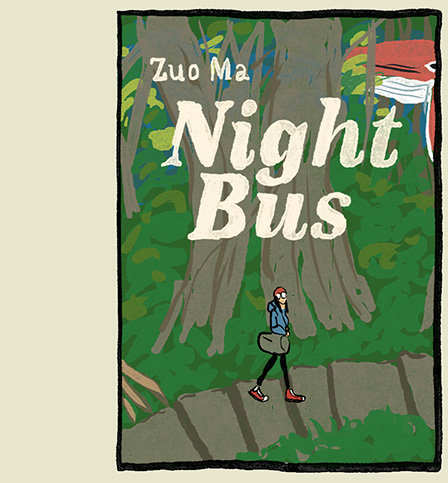

Night Bus

by Zuo Ma (translated by Orion Martin, lettered by Sophie Yanow)

412 pages

Published by Drawn & Quarterly

ISBN: 1770464654 (Amazon)

A collection of suitably bizarre short stories. They remind me a little of panpanya's work (maybe very lightly crossed with a brush of Junji Ito's aesthetic sensibilities). In an early story, a cat talks to the story's human protagonist, complaining that her life went so wrong that she had to hook up with a stray dog for comfort and that the dog has abandoned her and now her children (dog/cat hybrids) are cold and hungry. If that sounds like the kind of place you hang your hat, dive on in and be warmed and filled.

O Maidens In Your Savage Season

by Mari Okada and Nao Emoto (translation by Sawa Matsueda Savage, lettering by Evan Hayden)

8 vols

Published by Kodansha

ISBN: 1632368188 (Amazon)

Mari Okada is particularly known in film and television for her depictions of youth and youthful romance, with the playful, hesitant back-and-forth that denotes that kind bumbling, awkward attempt at wooing and at being wooed. And of course, much of the credit for those depictions in North American localizations of her work rests in the facility with which her mediators convey those raucous, delicate, hilarious conversations. Contrasting to her film work, in Okadaís first graphic novel series, O Maidens in Your Savage Season, the absence of actorsí inflections lending to the experience means much more weight is put on the translatorís work in painting a believable, entertaining story world for readers.

O Maidens is a book that could have gone horribly wrong. Four high school girls, each with their own situations and problems to overcome, are the four members of a classic lit club. They use their time together to read erotic scenes from classic literature aloud, exploring the curiosity for their own burgeoning sexuality in a safe way. The description sounds both implausible and very easy to get wrong. Still, despite expectations, what unrolls is a funny, poignant, and highly nuanced exploration of four individuals and their tumultuous coming-of-age stories. The feeling of the book swings from mood to mood: from funny to nerve-wracking to sweet to uncomfortable to thrilling to inspiring, and back and forth and around and about.

For a book about girls written by a woman and drawn by a woman, publisher Kodansha could have easily torpedoed their English-language edition by giving the job of translation to a man. Itís not so much that a man couldnít translate O Maidens well, but more a question of conveying trust. Even before opening the book, a reader will generally trust a woman to depict the intimate hearts of young women before they would a man. On top of this, Kodanshaís selection of Sawa Matsueda Savage is a delightful choice, delivering a crisp script that is sweet and scandalous, heartfelt and harrowing, and feels like it gets at something we donít often see in coming-of-age stories.

Little Monarchs

by Jonathan Case

256 pages

Published by Margaret Ferguson Books

ISBN: 0823442608 (Amazon)

Solid post-apocalyptic adventure yarn that's simultaneously probably geared at young readers with a 10yo (probably?) protagonist but also too complex for that age group generally.

So something in the character of the sun changed and everyone above ground died in contact with the sun's light. Now, like 60 years later, a girl and the scientist who's caring for her are researching a medicine to counteract the sun's damage. They use scales of monarch wings so they carefully follow the migrations along the American west.

At one point, they encounter a working Cybertruck, which is kind of hilarious.

It's a good book, mixing the grim with the light. Kind of like an adventure version of The Road. There's a giant Chekhov's gun dropped in the opening that never gets picked up and I'm still wondering if that was intentional or just careless.

Apsara Engine

by Bishakh Som

250 pages

Published by Feminist Press

ISBN: 1936932814 (Amazon)

Okay, so. I don't remember much about Apsara Engine beyond that I liked it. It's a collection of short stories and like all good collections I've seen, some stories are great and some are merely good. Some of the book's stories are futurist and others are set in the present. You should probably read this because I bet you'll kind of like it too. (Apologies for the lame review! I might do better later!)

infinite ©uck

by Joshua Cotter

32 pages

Published by Fantagraphics

Purchase from Fantagraphics)

I'd originally read this as Cotter was posting on Instagram as a break from Nod Away vol 3, and an escape from the chaos of the political sphere and how that was affecting his mental health, but now he's published the whole thing as a huge newsprint edition (like 20+ panels per page). It's a wild, goofy, dark comedy about him being a liberal in the South. The characterizations are a bit corny but that works in its favor and charm, I think. The drawings are in pencil so publishing on newsprint (it's like a small newspaper) loses a lot of the clarity, but that too is almost charming. It was only 2 bucks too, so that's nice.

Chainsaw Man

by Tatsuki Fujimoto (translated by Amanda Haley, lettered by Sabrina Heep)

11 vols

Published by Viz

ISBN: 1974709930 (Amazon)

Honestly, Chainsaw Man starts off pretty rocky, a mediocre shonen-y romp but gradually betters itself. It's hard to pin down, exactly. The book is like a mix of good funny bits + corny sex stuff that you read with a put-upon sigh + some great monster design + some decent monster design + some nice action pieces and great spreads + occasionally incomprehensible storytelling + these transcendent moments. The high point of the series is, hands down, the assassins arc. Lots of excitement, lots of nuttiness, and the best set-pieces of the series—a lot of those gorgeous pages (the astronauts, for instance) that have floated through the internet are from the assassination arc. I'm not sure where I ultimately come down on the series (except that it is definitely №68, no question). I really dug the assassination arc, which lands around chapter 60. I had to push through the first 40 chapters, buoyed by the sense of humor and some good paneling. The movie date with Mikama was solid. On the whole, it's an okay series with some great high points. The one thing it does REALLY well is pop in these surprising moments where someone's just having a normal conversation and in the next panel they're in five pieces. I rarely expected any of these and the abruptness of the mood shift always made me laugh.

I'll give it this though: I definitely plan to reread the whole thing when the second series finishes.

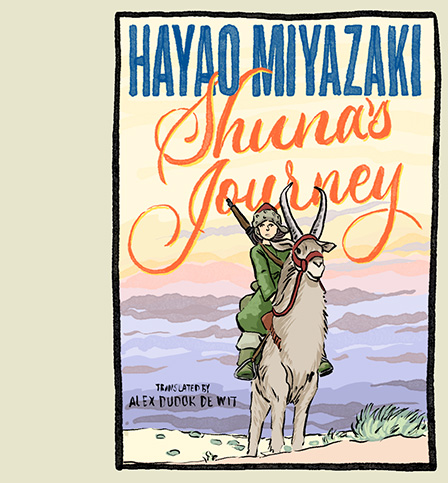

Shuna's Journey

by Hayao Miyazaki (translated by Alex Dudok de Wit)

160 pages

Published by First Second

ISBN: 1250846528 (Amazon)