Welcome to my annual attempt to share what I feel are the best comics of the previous year (in this case, the books of 2019). Before we get down to it, a caveat:

This year's list is almost entirely due to the use of the public library and their participation in interlibrary loan. Since losing my job a year and a half ago, we've shifted household activities around a bit, and I've been in stay-at-home-dad mode, spending my days with my two youngest children. This has meant that comics purchases have been reduced to almost nothing. With that in mind, there have been several books that I would have liked to get ahold of (like Angola Janga) that just aren't available to me yet.

Okay then, of course all the usual obnoxious caveats apply: a) that these lists are always only going to be a highly subjective record of tastes of a particular moment in a given segment of time; b) that it's virtually impossible and actually impossible to retain the same memory of a work read in January as it is of one read in November; c) that I of course haven't read a great many of the potentially fantastic works from across the year. All that's the same-ol' same-ol'.

Eligible for this list I'll be including:

- Comics printed in collected form for the first time in 2019

- Comics printed as books for the first time in 2019

- Comics printed as books for the first time in the US in 2018

- Comics published on the web in 2019

- Comics published through digital services like Crunchyroll in 2019

- Important comics reissued for the first time in many years

I believe that covers all my bases. Really though, I'm less interested in being a stickler for details than I am in just flat out recommending you some great comics reading from over the last year. So let's do that.

1–1011–2021–3031–4041–5051–6061–70

My Best 70 Comics of 2019

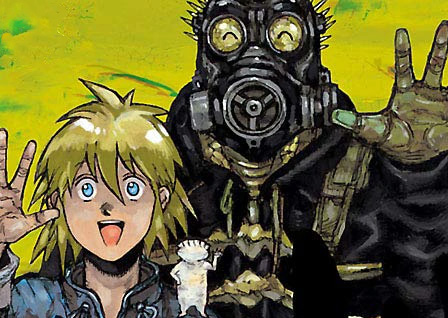

Dorohedoro

by Q Hayashida (translated by Hiroko Yoda and Matt Alt, lettered by Kelle Han and James Gaubatz)

23 vols

Published by Viz

ISBN: 1421533634 (Amazon)

Dorohedoro readthrough tweet thread

After nearly two decades of work, Japanese auteur comics creator Q Hayashida put a cap on one of the most astonishingly singular works in the medium. Working without assistants (uncommon in the kind of manga that exports to the US), Hayashida crafted a wild vision, ferociously grimy, simultaneously dark and buoyant, and always at liberty from the expected.

Dorohedoro is about wizards, about the downtrodden, about family, about revenge, about mystery, about gang warfare, about the illuminati-like machinations of devils. It's about learning who your friends are even when you don't know who your friends really are. It's about gyoza and how truly appreciating food can be the one thing that keeps things going.

At the end of the day, it's going to be very difficult to explain exactly why Dorohedoro is in my Top 20 Comics Ever Made. It's smart, it's funny, it's unexpected, sure. But it's also so many other intangible things. I suppose we can sum up with: it's art. Like in that “Are comics/games/anime Art?” sense that people unsure of the validity of their tastes like to wonder about. It's art-art. It would find itself happily placed next to Caravaggio in any reputable museum. For all the humdrum waffling involved in art-as-subjectivity, I'll tell you this: Dorohedoro is Citizen Kane, Casablanca, Godfather 2, and Silence. Dorohedoro is “Water Lilies,” “The Scream,” and “The Thinker.” Dorohedoro is The Great Gatsby, The Bell Jar and Lincoln In The Bardo. It's confusing, delirious, emboldening, hilarious, heartfelt. It's art-art, and it'll make you think if you let it.

The Book Of Forks

by Rob Davis

3 vols (the Motherless Oven trilogy)

Published by Self Made Hero

ISBN: 1910593737 (Amazon)

Motherless Oven, the first of Rob Davis' trilogy, was delirious and unexpected. A gorgeously drawn and intricately developed world off-kilter enough that one could be forgiven for thinking everything was just pure authorial whimsy. It's sequel, The Can Opener's Daughter proved that what seemed like whimsy was actually planned and formulated with devotion to a set of rules. This was world-building in the finest, most worthwhile sense. And with Book Of Forks we marvel at just how far Davis is willing to go to justify his world's existence, to outline its lore, to undergird its systems. Book Of Forks is Return Of The King sprinkled with liberal bits of Silmarillion and Christopher Tolkien's History Of Middle Earth.

When I first came to a page of text from the in-universe Book Of Forks (because the Book is something being compiled by Castro, one third of the books' protagonist trio), I was slightly put off, as I don't usually care to read prose within my comics. But once I saw what Davis was doing, my heart goggled. As the book continued, surprise stood upon surprise until I could only simply wonder, awe-struck at Davis' achievement here.

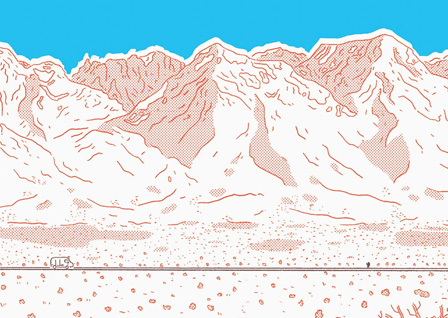

Americana

by Luke Healy

336 pages

Published by Nobrow

ISBN: 1910620610 (Amazon)

In Americana, Luke Healy recounts journal-like his progress along the Pacific Crest trail as he attempts (by his description) to gorge himself on America and thereby satisfy or purge himself of his affection for the deeply broken little nation/culture. I don't know that he was successful in that aim, but his achievements both on the trail and after, making this book, are laudable.

Americana was an important book for me because it allowed me to reinhabit (vicariously) a me that I will never be again. My affection for the outdoors was ferocious. I loved to camp, loved to backpack, loved other unrelated outdoorsinesses (such as skimboarding, boogieboarding, creeping around the tidepools). All of that was taken from me through a gradually developed set of injuries and conditions (some forged by my love of the outdoorsy activities themselves). It's been a decade since I last camped. In a campground. Next to my car. With an air mattress and other comforts. And that was too much for my body even then. Since then, I've acquired bone-eating tumours and degenerated discs, meaning walking for 30 minutes on even ground is extremely difficult. In short, I've been for too long cut off from one of my deep affections.

Healy's work here brought back in my heart's eye the experience of backpacking in the Sierra Nevadas two decades ago. Sitting with him through his joys and miseries along the trail returned me to my same experiences on my own trails.

It's a beautifully drawn book, evocative and tender, even while skirting the dark clouds of fear that the American national machine inculcates in all its children, foreign and domestic. My personal connection to the work certainly elevated my opinion of it, but even so, I recognize Healy's book as something special. Something with heart, something with soul.

The House

by Paco Roca

134 pages

Published by Fantagraphics

ISBN: 168396263X (Amazon)

In The House Paco Roca (also responsible for last year's Top 5 book, Twists Of Fate) breaks the walls of time and memory as we sit with the grown siblings (and their families) of a recently deceased man while they meet for a weekend to do work on the man's house, preparing it for sale. The siblings, each haunted by loves and regrets, each unique in personality and talent, bumble through their care for their father, their care for each other, and their affection for the house itself and come to a different place than when the weekend began.

It's a familiar sort of story, but Roca's ability to convey memory, time, and meaning through his art elevates what could have merely been another reunion story.

Invitation From A Crab

by panpanya

224 pages

Published by Denpa

ISBN: 1634429206 (Amazon)

In Invitation From A Crab panpanya gifts us with a set of haunted short stories, investigating our sense of the world through the oblique. Thoroughly mundane until thoroughly not, these are some of the cleverest, most fascinating stories I've read. They're cynical, but not in a negative way. They're skeptical, but not in a way that belies belief. They're richly imagined, they make me laugh, they make me consider. They're really weird but—and this sounds dumb—not really all that weird at all. I think you just have to give yourself up to panpanya's world. In any case, these are stories I'll return to a plurality of times over the years, especially when I want to investigate how an author can create a mood.

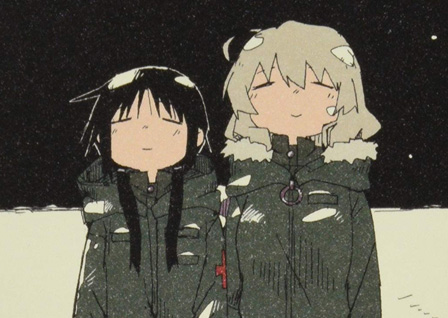

Girls' Last Tour

by Tsukumizu (translated by Amanda Haley, lettered by Abagail Blackman and Xian Michele Lee)

6 vols

Published by Yen Press

ISBN: 0316470627 (Amazon)

Girls' Last Tour readthrough tweet thread

Tsukumizu's Girls' Last Tour is a wonderful book. Cute, thoughtful, morbid, and filled with humanity. It's about two teenagers, Chito and Yuuri, who ride around the post-war ruins of civilization on their halftrack both trying to pass the time and trying to survive. The need food, water, shelter, and fuel, and as they putter around acquiring these, they chat about stuff. What music is, what god is, why people go to war, what's worthwhile, what cheese is. Stuff like that. They need each other and while they're very different in personality and interests and intelligence and ability, they are pretty much all they have. There're not really any other people around. One here, one there, but food is scarce and so is the will to keep living. One person they meet hasn't seen anyone in so long that he starts choking when he tries to use his voice.

Despite the brevity and abortive nature of the girls' forays into the philosophical, their conversations are lent gravitas by their context. It's a kind of shorthand that works really well. Then there are these pretty out-of-the-blue moments of sublimity that can strike in such a way that beauty and thoughtfulness transcend the page and threaten to make the readers exterior life more beautiful as well. It's a good book that tries to deal with hopelessness in a manner that is warm, cozy, and not entirely depressing—even if it can't avoid it entirely. I mean, it's right there in the title.

Pittsburgh

by Frank Santoro

216 pages

Published by New York Review Comics

ISBN: 1681374048 (Amazon)

Using an art style that reminds me of Santoro's earlier work, Blast Furnace Funnies, Pittsburgh sings visually in a romance of pinks and greens, yellows and purples. Less a monument to the foundational characters (Santoro's divorced for two decades parents) and more an evocation of a place and time, Pittsburgh still brings these two people to life in surprising ways. There are, as well, moments that shock, horrify, and underline the sickness embedded in the human endeavor. In the end, the book doesn't answer the question it proposes about Santoro's parents, leaving their relationship and future sketched as lightly, wildly, and ephemerally as he draws the city around them.

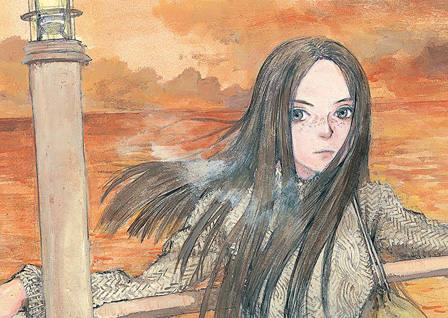

Emanon

by Shinji Kaijo and Kenji Tsurata (translated by Dana Lewis, lettered by Susie Lee)

3 vols

Published by Dark Horse

ISBN: 1506709818 (Amazon)

[Inconsequential spoilers ahead] While I suspect that Tsuruta may have been happy to make Emanon as a good excuse to draw a pretty girl over and over (very much in the wheelhouse of Wandering Island), the story is probably what inspired him to stay on. It makes great sci-fi (set, primarily so far, in 1967).

Emanon has a secret. She's 17 and remembers everything she's experienced. And not just from those 17 years, because the "she" inhabiting her has never ceased to be from the beginning of planetary life. Emanon estimates that she is 3 billion years old. Every time she reproduces, her consciousness (and memories) moves to the next generation.

It gets pretty wild. Neat concept with excellent execution and gorgeous Tsuruta art.

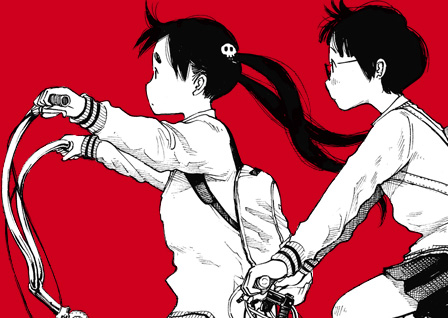

Dead Dead Demon's DeDeDeDe Destruction

by Inio Asano (translated by John Werry, lettered by Annaliese Christman)

7 vols

Published by Viz

ISBN: 142159935X (Amazon)

Dead Dead Demon's readthrough tweet thread

Dead Dead Demon's is the most blatantly satirical work we've seen from Asano in the US. Diabolically eviscerating facets of the contemporary millieu, it presents clueless socialmedia heroes and pastiche culture warriors in a way that is simultaneously compassionate and callous. Asano invites the reader to wonder at the implications of their own small decisions and how they implicate us in the larger calamity of the Way The World Is. DDDddddD pits a hawkish lust for violence against the backdrop real violence and the society that permits and ignores it and revels in it. I don't want to speak for Asano (his work will speak for itself), but my sense is that DDDddddD rightly pins us all as culpable in the tremendous number of failings in our societies.

I don't know if this is my favourite work of Asano's but it may be.

The Adventures Of Alexander Von Humboldt

by Andrea Wulf and Lillian Melcher

272 pages

Published by Pantheon

ISBN: 1524747378 (Amazon)

Wolf and Melcher tell the story of Alexander von Humboldt's South American adventures and explorations and experiments through a mixed media comics story that aesthetically reminds me of bits of Caitlin Cass mixed with Duncan The Wonder Dog. If you've got any interest in the naturalist or his body of work, this large book should be a delight.

Penny Nichols

by MK Reed, Greg Means, and Matt Wiegle

208 pages

Published by Top Shelf

ISBN: 1603094482 (Amazon)

Penny Nichols is sharp and funny. There was a point where I, sitting at the patio table in my backyard late at night, had to put the book down for a good couple minutes 'til I could compose myself and stop laughing. It may have just been a regular funny moment and not the king of all funny moments, but for whatever reason, it hit me exactly right, the perfect, practical absurdity of it.

Penny Nichols, a forgettable title for a book filled with amusing schlock horror titles is about Penny Nichols, a 26-year-old woman who has no ambition, has little interest in much of anything, and moves from temp job to temp job, just whatever it takes to make rent on the apartment she shares with a roommate she hates. Then comes the horror.

At a health expo (where she's temping for the day), she meets two indie horror filmmakers, and the ball gets rolling. They make the low budget/no budget stuff like the original Evil Dead. Big on splats, big on camp. They're making a new film—their best yet—and Penny's going to help them. They invite her as an extra but soon she's doing their book-keeping, scheduling, animal wrangling, assistant editing, prop management, acting, scripting, and directing. And more. Basically everything. For free. She kind of slips into it without realizing, but eventually she's all-in for the love of the game.

It's got a great little arc about Penny becoming a better person, finding that One Thing that will allow her to become a better person, but really that's all just icing on the cake. A cake filled with squibs. And laughs.

Skip

by Molly Mendoza

168 pages

Published by Nobrow

ISBN: 1910620424 (Amazon)

Skip is probably the most ambitiously beautiful book of the year. It's a futuro-fantasy story in which a survivor from a far-off AI apocalypse gets sucked into a fantastic world and then, with one of that world's inhabitants, sucked into world after world after world. All of this allows Mendoza to use myriad styles and palettes, each to depict another kind of reality. Mendoza is prodigiously talented and some of her spreads in the book astonish.

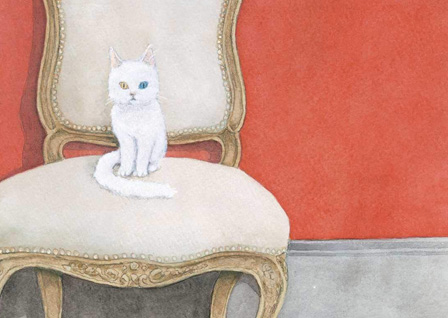

Cats Of The Louvre

by Taiyo Matsumoto (translated by Michael Arias, lettered by Deron Bennett)

168 pages

Published by Viz

ISBN: 1974707083 (Amazon)

Another in the Louvre's library of comics in which they allow superstars of the medium to tell stories so long as they involve the museum. This one fares better than Taniguchi's Guardians Of The Louvre, following a collection of feline strays who make their home in the attics of the Louvre. One cat, Snowbebe, has the ability to leap into paintings, drawing to a close a mystery that's haunted the museum for the better part of a century.

This doesn't carry the meaningful human weight of Sunny or the mystery of Gogo Monster, but it's substantial all the same and a delectable treat.

Stand Still Stay Silent

by Minna Sundberg

Read here

As the second Stand Still Stay Silent story finally journeys deep enough into the Silent World to bring the terror, we're reminded that Sundberg can be really deft at keeping readers anxious for the lives of her characters. The first journey held some truly heartbreaking moments along with those of deep beauty, and now the second journey seems poised to do similarly.

In Waves

by AJ Dungo

368 pages

Published by Nobrow

ISBN: 1910620637 (Amazon)

I grew up in surf culture, a son of the waves. My dad was a surfer (at age 73, he still surfs whenever he's in town) and we lived a 2 minute walk from a point break and the sweetest left I've ever ridden. For all that, I've never surfed. I boogie boarded, skimboarded, skateboarded, and body-surfed, but in that way that kids can be tragic punk a-holes, I always demurred whenever my dad offered to teach me to surf. He would have loved to share his great passion with me but I was too much of a stubborn little ass to allow him that happiness (I think I subconsciously feared not being any good at it too). And now, of course, it's far too late.

None of that childlike fussiness has stopped me, however, from appreciating surfing - or from understanding *just* how it feels to be out there in the line-up, anticipating the next set, enclosed in the green room, feeling that rush of jubilance when it spits you out again. As with AJ at book's end, I went out alone more often than not. It was a comfort and I look back on those days with fondness.

All that is to say that when I cracked open AJ Dungo's book In Waves, I was happy to see another graphic novel devoted to surfing. I feel like they're pretty rare. I've read two others, Pat Grant's Blue, which focuses on surfing and immigration, and Kim Dwinell's Surfside Girls, which is more of a ghost mystery with protagonists who also happen to be surfers. (Incidentally, while Grant is in Australia, both Dungo and Dwinell are local to Southern California, which makes me happy.) In Waves though may be the first I've read that is properly *about* surfing.

Or at least half of it is. Dungo skips back and forth in history, telling two stories. In earthen tones, he unspools the history of surfing, largely through two figures, Duke Kamehameha and Tom Blake. In water tones, he speaks of love and loss, remembering his girlfriend Kristen who would die in 2016 at age 24 of cancer.

It's a fresh work of grieving, a tribute to a woman and to the sport she loved and shared (Dungo took up surfing himself despite a fear of the sea, inspired by Kristen). Whether intentionally or not (probably intentionally), Dungo sets up the pair of Duke and Blake as a reflection of Kristen and himself, with Duke and Kristen being these larger-than-life figures of passion and inspiration and Blake and himself seeking comfort from brokenness in the break. It's a delicate work of simplicity and heart. It was worth my time and may be worth yours.

The Queen Of The Sea

by Dylan Meconis

400 pages

Published by Walker Books

ISBN: 1536204986 (Amazon)

With The Queen Of The Sea Dylan Meconis has crafted a book accessible to upper elementary-aged children but still rich enough to reward older readers. Developed as sort of a based-on-a-true-story alt-history, Meconis introduces Margaret, an orphaned girl living a peaceful life on an isolated island, home to a small convent. What Margaret views as an idyllic life is about to be torn asunder by the politics and intrigues of Albion (England by another name). Daily living, adventure, mythology, and information about how the world works tangle together to weave a beautiful tapestry—and one I look forward to reading more of in the book's follow-up in 2022.

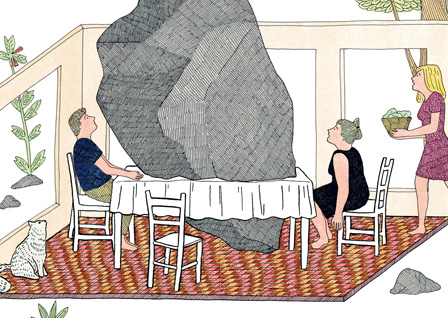

The Tenderness Of Stones

by Marion Fayolle (translated by Geoffrey Brock, lettered by Dean Sudarsky)

144 pages

Published by New York Review

ISBN: 1681372983 (Amazon)

For all its careful and detailed drawings, The Tenderness Of Stones offers, really, a rather impressionistic experience, depositing the reader in the midst of reflections on the narrator's (and author's) father's bout with what I gather to be lung cancer (or something similar). The technique used is distancing, which helped keep me from being bowled over my the emotionality of loss—but simultaneous offers a different kind of avenue into the circumstances of watching a loved one gradually diminish. It's a strong book and a weird book.

Mighty Jack And Zita The Spacegirl

by Ben Hatke (coloured by Hilary Sycamore and Alex Campbell)

6 vols

Published by First Secon

ISBN: 1250191726 (Amazon)

Wrapping up (I think) both the Zita The Spacegirl and the Mighty Jack series, Ben Hatke delivers a satisfying conclusion to his characters' adventures (which really is just the jumping off point for many more adventures, untold but not unexpected. Hatke does something fascinating for an adventure series and caps the whole thing off with a pacifistic solution. It's not a common direction for a swashbuckling series that has had plenty of fighting up to this point, and I appreciated the surprise of it. Hatke's work has long held a special place in my heart and I'll certainly look forward to whatever he's got coming down the pike.

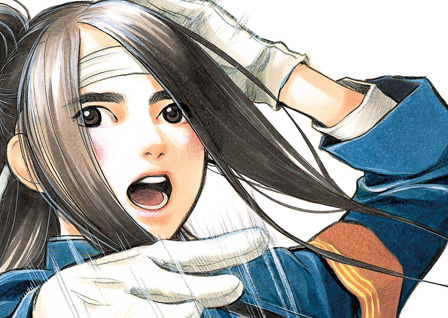

Vinland Saga

by Makoto Yukimura (translated by , lettered by )

11+ vols

Published by Kodansha

ISBN: 1612624200 (Amazon)

With vol 11, Yukimura wrapped up the long Baltic Sea War arc, the third act of the series and is set to head into his finale, which will be at least as long. Thorfinn continues to navigate his pacifistic ideals in the midst of a people who prize violence, fighting, and the valor of dying in battle. But it wears on him. It would be so much easier for him to solve his problems through violence, but he's aware by now that this would be no solution.

O Maidens In Your Savage Season

by Mari Okada and Nao Emoto (translation by Sawa Matsueda Savage, lettering by Evan Hayden)

5+ vols

Published by Kodansha

ISBN: 1632368188 (Amazon)

Five teen girls form the high school's literature club. They read great, usually rather contemporary, works of literature. If you've read basically any books written for adults in the last 100 years, you're aware that good books for grown ups often contain sex scenes.

These girls, naive in sexual matters, are trying to navigate the boundaries of the transition into adulthood, and their literature club lights a need to understand in them. The journey is raucous, true, heartfelt, and awkward. And by Okada's pen, very very funny.

Even in the first volume I found myself in Starbucks stifling laughter as the main character, embarrassed to be thinking about sex, Just Cannot Stop thinking about sex. It's a funny pericope and it's not alone.

O Maidens In Your Savage Season will appeal to both male and female readers. Its subject matter, though focused on female experiences of sexual awakening, really is pretty universal. The book recently received praise from several quarters at the SDCC manga industry roundtable.

Delicious In Dungeon

by Ryoko Kui (translated by Taylor Engel, lettered by Abigail Blackman)

7+ vols

Published by Yen Press

ISBN: 0316471852 (Amazon)

As more and more of the workings of the dungeon are revealed, Delicious In Dungeon also seems to be angling toward, if not a conclusion outright, then at least a framework by which a conclusion might be developed. The book continues to be a joy, full of warm-heartedness and humour, but now begins to more propose a narrative structure away from simple monster-of-the-week fun.

Land Of The Lustrous

by Haruko Ichikawa (translated by Alethea Nibley and Athena Nibley, lettered by Evan Hayden)

11+ vols

Published by Kodansha

ISBN: 1632364972 (Amazon)

SYNOSPSIS: The world is very different than it was. There are, essentially, three forms of life: the mollusks, the Lunarians, and the gemstones. And Sensei, whatever he is. The Lunarians attack the gemstones fairly regularly for reasons unknown. The gemstones are smartly dressed creatures (coded as vaguely androgynous women) whose toughness and character is related to the Mohs scale of the gem from which they're formed. Most of them are hundreds of years old. This story concerns Phosphophyllite, a fragile and pretty useless gem, as it investigates the world and seeks to understand the Lunarians and the Sensei.

Land Of The Lustrous is kind of amazing in how rapidly a story about incalcitrant, functionally immortal beings evolves and changes. Some of these characters are 700 years old and harder than steel, but the youngest of their group breaks and remolds and grows and shifts in both form and personality and motivation. She doesn't just have a character arc; it's more like a character squiggle.

And the story continues to evolve dramatically. It's impossible to predict what's going to happen next. I mean, sure, one might expect a manga time skip here and there, but one that's more than 100 years and is the one time the story doesn't principally change? Didn't see that coming.

BTTM FDRS

by Ezra Clayton Daniels and Ben Passmore

288 pages

Published by Fantagraphics

ISBN: 1683962060 (Amazon)

BTTM FDRS is a sci-fi horror story set in a contemporary millieu and Daniels uses the occasion to deliciously poke at race, gentrification, Whiteness, and class privilege. Brilliantly fun.

Ooku

by Fumi Yoshinaga (translated by Akemi Wegmuller, lettered by Monalisa De Asis)

16+ vols

Published by Viz

ISBN: 1421527472 (Amazon)

For years I've been thinking that Ooku could satisfactorily end almost at any time, but now I'm guessing we could get up to four more volumes, taking the narritive to the close of the Shogunate. In any case, Yoshinaga continues to surprise with her twisting alt-history/secret history to Tokugawa Japan. After we finish off this current Shogun's reign (probably in vol 17), there is only one more Shogun remaining before the dissolution of the Shogunate and the beginning of the Boshin War. The collapse of the Shogunate, of course, ends the existence of the Ooku (that is, the titular Inner Chambers), so I can't imagine the series moving beyond that much. In any case, Ooku has positioned itself as one of the greatest, most intricate comics of all time. Truly a masterpiece.

The Seventh Voyage

by Jon J Muth (adapted from Staislaw Lem's The Seventh Voyage)

80 pages

Published by Graphix

ISBN: 0545004624 (Amazon)

This is the funniest time travel story I've ever read. Muth, adapting one of Stanislaw Lem's Ijon Tichy short stories, creates a bizarre, old-timey aesthetic for the story that works perfectly. The only flaw, perhaps, is that the lettering is weak.

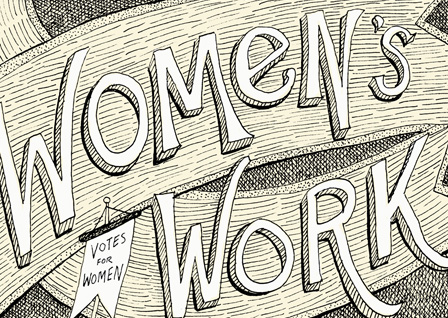

Great Moments In Western Civilization: Women's Work

by Caitlin Cass

Self-published

Subscribe here

I've been a fane of Great Moments In Western Civilization for years now, often delighting in Cass' skewering of the ludicrous people, beliefs, and happenings that weave together to form the foundations of the moment at which we now stand (itself a ludicrous moment), but this last year's work has been a wonderful series of reflections on women's suffrage, telling the stories of women and the worlds that stood in conflict against them. I very much hope Cass will find a way to compile this disparate works into a single volume, making them easily accessible to schools and the teachers who could readily emply them.

Two Dead

by Van Jensen and Nate Powell

256 pages

Published by Gallery 13

ISBN: 1501168959 (Amazon)

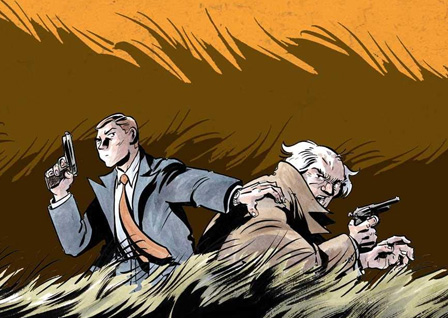

While I love Nate Powell's auteur work most of all, I still will take any opportunity to enjoy his illustrations. With Two Dead, he and writer Van Jensen craft a tense, police thriller set in the postwar American South. Based on true accounts of policework, crimes, and personalities of the era and locale, Two Dead seethes at the too-great power wielded by the police forces intended to keep order and protect justice. It's a dark ride that won't end well for many of its characters. Which is also true to life.

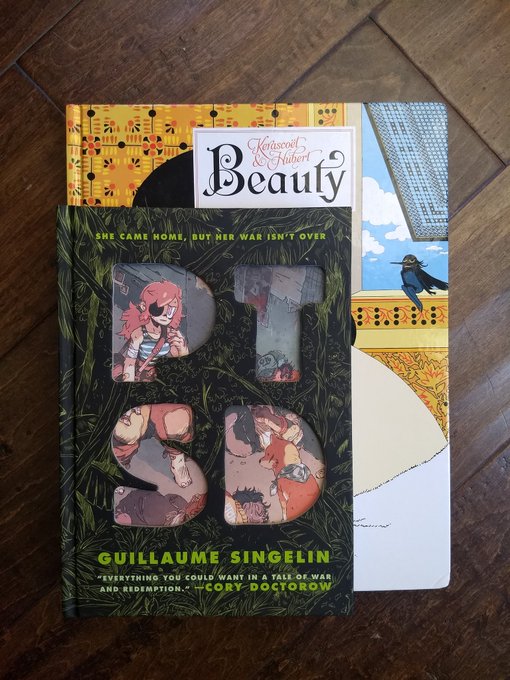

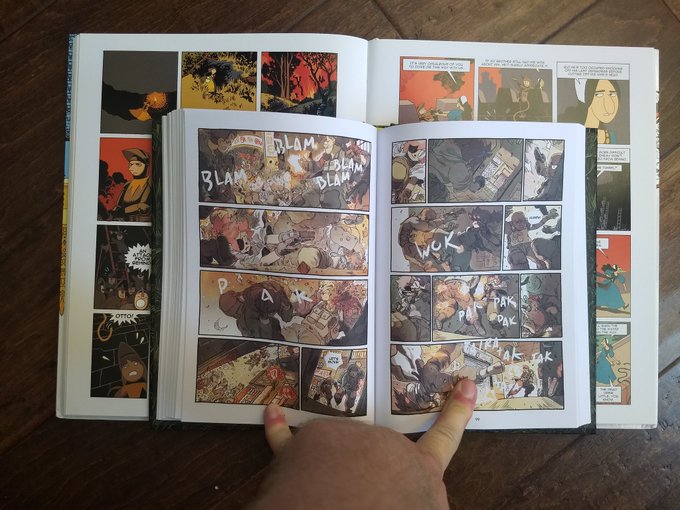

PTSD

by Guillaume Singelin (translated by , lettered by )

208 pages

Published by First Second

ISBN: 1626723184 (Amazon)

Singlin in PTSD has delivered a visually lush experience, a city both metropolitan and traditional, thriving and beaten down. His art is filled to gill with detail and bursting with colour. Into this gorgeously designed set, he litters homeless and often helpless vets from a now-finished war. These are humans, hurting and hardened, but simultaneously they are the waste product of nationalism, of militarism. They are the trash that these anonymous systems create in order maintain their power structures. And the war that produced them is just as murky as any of the recent ones that my own country (America) has perpetrated. In flashbacks to the field, soldiers complain that they no longer know what they're fighting for - since how can a soldier cut off from decision-making understand the mechanism that keeps him fighting for what only ever amounts to greed or fear or self-aggrandizement.

Into such a post-war society, Singelin gives us Jun, a former sniper in an eyepatch. She suffers from anxiety and trauma. She had a team she relied upon and who relied upon her, but now she's alone by choice. Her problems are nobody's and nobody's problems are hers. Only, in a society, this is never the case and we share each other's burdens whether we wish to or not.

Singelin's message or moral is pretty simple and a common one throughout the history of film and literature: help and get help, no man is an island. But regardless the commonality of the story and its beats, Singelin delivers something fresh through his blisteringly good art. The action scenes feel like Otomo in Akira. In the backmatter, he references a lot of films that influenced this book, from Hurt Locker and The Deer Hunter to Hard Boiled to Tampopo (Tampopo!), and it's easy to see how PTSD enters into the continuing conversation by cribbing from these stories and evolving those cribs into his own contribution.

If there's one thing I have against PTSD, it's that in the US release of the book, the publisher reduces its size by 20%. That may not seem like much (it's just 20% after all), but compare here with PTSD laid over a book the size of its original edition.

In a book where the detail in the art plays such a monumental part, this reduction feels like a tremendous loss. Especially for those of us with older eyes.

This Was Our Pact

by Ryan Andrews

336 pages

Published by First Second

ISBN: 1250196957 (Amazon)

Around a decade ago, Ryan Andrews released an 80-page, black-and-white story about two kids on bikes that run into a bear. It was outstanding, a quick-punch tale of whimsy and wonder. A little while later, he announced that First Second had picked it up and would be releasing it in print.

Years and years later, that book is here. With all-new art (in colour this time) and 250 extra pages of story, Andrews gives us the same story that is also a whole-different story.

While the old version as perfect for what it was, the new one crackles with a different kind of vitality. Where the original seemed built to affect the feelings of thirty-somethings remembering their childhood adventures, the new one best targets a different kind of reader, those still in the midst of their youths, with adventures still in store.

It's a beautiful book and both my reading kids have been through it several times already.

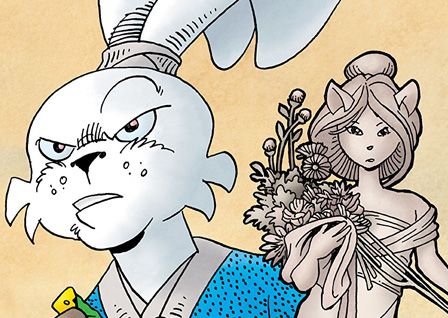

Usagi Yojimbo

by Stan Sakai

33 vols

Published by Dark Horse

ISBN: 1506708528 (Amazon)

Usagi Yojimbo readthrough tweet thread

This story, "The Hidden," is the last volume of Usagi to be published at Dark Horse. It's a fitting send-off, dealing with themes of religion and following convictions. Christian persecution has come to Usagi's world and as he and Inspecter Ishida (along with folk-hero thief Nezumi) follow the mystery of a foreign box. Sakai uses the probably-familiar-to-American-readers sense of Christianity to highlight how alien those principles would have been to a man (rabbit) so deeply devoted to the honour of the way of the samurai. It's a fascinating journey and Sakai continues to show why he's one of the shining stars of the comics form.

Vattu

by Evan Dahm

3 vols

Self-published

Read here

As Dahm nears the conclusion of this epic, everything is falling apart for everyone. The Empire is changing hands or in the process of collapse. Vattu is set adrift, having accidentally delivered the killing stroke to her own hopes. Jinti has pushed the Surin to the breaking point. Kadrash readies to flee as the Grish are stoked to calamity. And what of the Warmen?

Exciting things, beautifully drawn, written with the firm stroyteller's voice that Dahm's established over the last fifteen years of his Overside chronicles.

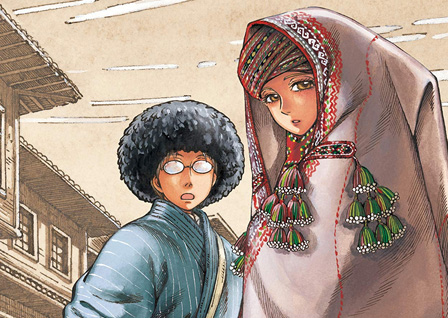

A Bride's Story

by Kaoru Mori (translated by William Flannagan, lettered by Abigail Blackman)

11+ vols

Published by Yen Press

ISBN: 0316180998 (Amazon)

A Bride's Story readthrough tweet thread

Vol 11 of A Bride's Story picks up a narrative thread I'd assumed dropped back in vol 2, and does so to the happiness probably of most of Mori's readers. Mori even includes a full chapter devoted to the question of What Happened To Smith's Watch!? Also, a cool chapter about mid-19th century photography and how delicate the chemical admixture required to produce images at that time.

Witch Hat Atelier

by Kamome Shirahama (translated by Stephen Kohler, lettered by Lys Blakeslee)

5+ vols

Published by Kodansha

ISBN: 163236770X (Amazon)

The art of Witch Hat Atelier is stunning. It looks almost exactly as if Arther Adams followed The New Mutants: Special Edition #1 by tempering himself and taking his structural cues from manga instead of diving deep into whatever it was that turned him into whatever it is that can churn out bizarre thigh after bizarre thigh. The linework and detail is stunning, and the pages are filled with so much exuberance. The story seems like it's going fun places, but I've only read 3 vols so far, so we'll wait and see on that count.

The Tower In The Sea (Ismyre books)

by B. Mure

3 vols

Published by Avery Hill

ISBN: 191039534X / 1910395439 / 1910395498 (Amazon links)

I only discovered B. Mure's Ismyre series this year, so I had the privilege of reading Ismyre, Terrible Means, and The Tower In The Sea across a single week. What beautiful art. Mure develops these so far unrelated stories within a world of magic and corruption and beauty and greed. Each is wonderful on its own, but as they build their own stories, Mure's world begins more and more to gain solidity. And as these are so wonderful, that's a good thing. I don't know if there's more in the work, but I dearly hope there will be.

Through A Life

by Tom Haugomat

184 pages

Published by Nobrow

ISBN: 1910620491 (Amazon)

Through A Life is a great experiment that reminds me of 750 Years In Paris (also published by Nobrow). The book is silent and each pair of facing pages are a duo tied by a device. On the verso page, Haugomat shows us a single illustration of the main character (undergirded by a date and a location so we can track age and place of our protagonist), and on the recto page, we see what the character on the verso is seeing. So on on page we might see a toddler standing at the bath, looking out a four-paned window; on the facing page we see that boy's father, outside on the porch at night, our view divided into four panes. It's experimental, for sure, with no dialogue and no standard comics paneling, but it really does work, providing a view of a life through a series of snapshots, sometimes important moments, sometimes less so.

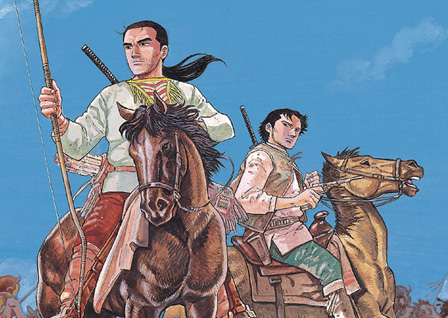

Sky Hawk

by Jiro Taniguchi (translated by Kumar Sivasubramanian, asst by Chitoku Teshima)

288 pages

Published by Fanfare/Ponent Mon

ISBN: 1912097346 (Amazon)

Somewhat an homage to the bande dessinées westerns he grew up on (Blueberry, Cartland, Comanche, etc), Taniguchi created a story of Japanese involvement in the conflict between General Custer and the Souix that is as gorgeously drawn as you would expect.

Fleeing to American after the Boshin War, Aizu samurai Hikosaburo and Manzo work in a mine until everything falls apart and they are on their own. Driftless, they ingratiate themselves to a Crazy Horse's Souix tribe and become fast friends through shared values. Hiko is an expert archer with the long bow and Manzo excels at jiujistu; they train Souix warriors as they can but rise in esteem eventually becoming Souix heroes, Sky Hawk and Winds Wolf.

In the end, as fantastical as the idea of these two samurai Lone-Wolf-And-Cubbing their way through Custer's forces is, it's pretty epic. And while Taniguchi's story means two Japanese share victory over Custer in the Black Hills engagements, he does not lessen the strength and leadership of Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull (who only appears in cameo). Further, Hiko and Manzo fully dwell within their part within the Souix citizenry - as with many naturalized citizens, they find themselves eager to be the best representatives of their adoptive nation.

The book ends with a letter from Taniguchi, penned in 2009, wondering what American audiences would think of his mucking around with their history and culture. He considered that he might like to do more. Finally seeing light 2 years after his death at age 70, it is with sadness that I report that I loved this book and would eagerly look forward to more of his vision for the West had time allowed for it.

Blank Canvas: My So-Called Artist's Journey

by Akiko Higashimura (translation by Jenny McKeon, lettering Lys Blakeslee and Katie Blakeslee)

3+ vols

Published by Seven Seas

ISBN: 1642750697 (Amazon)

Blank Canvas is Akiko Higashimura's memoir telling the story of how she went from listless, lazy, and self-important highschooler with visions of artistic grandeur to mangaka creator of Princess Jellyfish and Tokyo Takareba Girls. And while I enjoyed both those series and typically find memoir a chore, Blank Canvas is pretty easily my favourite work of hers. It's likely due to Higashimura's sense of humour that she turns the story of a pretty petulant little butt of a girl into something engaging, fun, and enlightening.

Hawking

by Jim Ottaviani and Leland Myrick

304 pages

Published by First Second

ISBN: 1626720258 (Amazon)

One of my favourite science biographies was Ottaviani's and Myrick's Feynman from several years back. Seeing the creative team return to tell the story of another scientist I was barely acquainted with was exciting. After several brain injuries over the last few years I'm left at a place where I struggle much more to understand the science being described, but it was still nice to see the human side of Hawking's life developed and described. Also, I'm glad I was not his wife. I mean, I wasn't in the running. But still.

Blossoms In Autumn

by Zidrou and Aimée de Jongh (translated by Matt Madden, complicated lettering attribution described here)

144 pages

Published by Self Made Hero

ISBN: 1910593621 (Amazon)

It's a nice, quiet book, about two older people (56yo man and a 62yo woman) falling in love. It's got a couple surprising turns, but generally it's just about love and wrinkles. More than anything though, I loved that De Jongh doesn't shy away from drawing folds, fats, and stretch marks. It's not something we see enough in comics.

The Princess Beast

by Sarah Burgess

Published online

If you want reliable romance comics, you're largely going to be spending your time on Japanese productions. They've kind of got the romcom nailed down at this point. My Love Story, Horimiya, Cross Game, Princess Jellyfish, O Maidens In Your Savage Season, ad infinitum. If however you'd like to read English-language romcoms, books that are foremost written for the reader immersed in English-language culture, there are only a handful of guiding lights. Andi Watson and Chynna Clugston were big around Y2K. Bryan Lee O'Malley shone for a time. There are a new crop of good romances from contemporary creators (such as Jen Wang's Prince And The Dressmaker), and then some that just didn't land quite right for me due to what felt like writing stumbles (Kiss Number 9 and Laura Dean).

Among my favourite of the last few years is Sarah Burgess. I featured her 4-volume comic The Summer Of Blake Sinclair in spot 246 of this series. And now she's been working on a new one, The Princess Beast. It's still pretty early in the story but I thought some of you might like to get in on it.

The Princess Beast seems like an idea spun out of Moto Hagio's story "Iguana Girl." The main character is a princess named Princess. She looks to everyone like a pretty young princess, but Princess looks in the mirror and sees the truh: she is a beast. It's about her and a beastly (but cool) prince. And presumably about love.

Burgess has a great voice for romance. She writes lively characters that can carry a banter. Her art is fantastic for the wide variety of expressions necessary to pull this kind of thing off.

Again!!

by by Mitsurou Kubo (translated by Rose Padgett, lettered by EK Weaver)

10+ vols

Published by Kodansha

ISBN: 1632366452 (Amazon)

Synopsis: It's high school graduation and bleached long-haired loner Imamura is friendless and scary. Through an accidental fall on an apparently magic staircase, he and popular girl Fujieda get sucked back into their 10th grade selves. Fujieda finds her knowledge of the future is screwing up everything for her but Imamura joins the school's ouendan cheer squad (ouendan is a loud chant-based kind of traditional Japanese cheerleading). And things, of course, develop from there.

If you're looking for something in the vein of A Distant Neighbourhood but not done by one of the great masters of comics and more silly and fun, Again!! might strike the right note for you. There's a lot of heavy stuff going on in the world and you're allowed to get comfy with some lighthearted stuff every now and then.

Ajin: Demi-Human

by Gamon Sakurai

14+ vols

Published by Vertical

ISBN: 1939130840 (Amazon)

As Ajin barrels closer and closer to its conclusion, things grow more and more cataclysmic. Japan's leadership is being picked off one by one, and an IBM flood has been unleashed. I've no idea how this whole nutty thing is going to wrap but it remains exciting.

Island Book

by Evan Dahm

288 pages

Published by First Second

ISBN: 1626729506 (Amazon)

Island Book is much less complicated than any of Dahm's Overside books (I don't think Island Book is an Overside book but I may be wrong). It follows a simpler, fable-esque structure, but contains Dahm's usual, beautiful, spare cartooning. It's a little bit Moby-Dick and a little bit Voyage Of The Dawn Treader, but still it's its own thing, and I look forward to seeing how book 2 expands on the theme.

Girl From The Other Side

by Nagame (translated by Adrienne Beck, lettered by Lys Blakeslee)

8+ vols

Published by Seven Seas

ISBN: 1626924678 (Amazon)

Girl From The Other Side is still one of the most lovely looking books published every year, though in honesty, I wished it would have wrapped by now. It continues to be good but, at least right now, I feel the book is at its best when Shiva and her Teacher are just sitting around making house, rather than encountering the kinds of conflicts that Story demands.

Grass

by Keum Suk Gendry-Kim (translated by Janet Hong)

480 pages

Published by Drawn & Quarterly

ISBN: 1770463623 (Amazon)

This was a good year for history comics that remind us of just how completely awful the human race is at being remotely not savage. We have They Called Us Enemy, which reminds us that America kept its Japanese resident in concentration camps during WWII because we were too racist not to. We also got 442, which reminds us of the same but also that we asked those imprisoned Japanese to prove their loyalty by fighting and dying to defeat the Axis forces in Europe. And now we have Grass, which reminds us that during the same period Americans were imprisoning Japanese because they were Japanese, Japan was kidnapping Korean girls and shipping them to China to serve as sex slaves to soldiers on the Manchurain front. Go, Team Humanity.

Grass is biographical and based off interviews with Lee Ok-sun regarding her time as one of the "comfort women," among the most digusting euphemisms coined. It's a well done book with some harrowing artistic sequences.

The Envious Siblings

by Landis Blair

240 pages

Published by W.W. Norton

ISBN: 0393651622 (Amazon)

Landis Blair (of The Hunting Accident)is making rad stuff. Along with Whetting Engines, a strange, haunted book devoted to gorgeous illustrations of some of his favourite pencil sharpeners intruding on daily life, Blair released The Envious Siblings, a collection of morbidly funny tales to delight. There are some real gems in here.

While we were at back-to-school night, my ten-year-old daughter read some to our two-year-old and reported back that it was disgusting. The next night I found her reading it on her own. I said, "I thought you said it was too gross?" Her response: "Yes, but I can't stop!"

The Hard Tomorrow

by Eleanor Davis

152 pages

Published by Drawn & Quarterly

ISBN: 1770463739 (Amazon)

Taking place in America in the slight future, one that looks much like the present only slightly further down a more fascist trajectory, The Hard Tomorrow is a beautifully drawn story about the future and the potential rememdy to that future. The lead figure is a basketcase whose heart is (mostly) in the right place. She protests abuses of state while nursing a deep crush on one of her comrades. Meanwhile she and her partner, a good-natured but lazy agriculturalist, are trying to get pregnant.

My first impression of the book was more negative. I didn't like the people inhabiting the story. They were naive, scattered, and loony. On reflection though, they do seem real enough. Would I have preferred to read about activists who seem mentally secure, rational, reasonable? Sure. But Facebook and Twitter regularly show us that the people (not just activists) we know very very often are not rational or reasonable. We're all so led by our fears and by our vaguely formed sense of self-righteousness. Taking that into account and the several breath-taking or well-observed moments in the book, The Hard Tomorrow grows on me more and more. And its finale is beautiful.

Beastars

by Paru Tiagaki (translated by Tomoko Kimura, lettered by Susan Daigle-Leach)

4+ vols

Published by Viz

ISBN: 1974707989 (Amazon)

Beastars is just getting revved up. While 3 vols landed in 2019, I've only gotten to the first two so far. It's a series with a ton of potential, but it's tough to judge just how good it is so far.

Zootopia-like (minus the kid gloves), Legoshi's highschool is populated by animal students who roughly divide themselves into carnivore and herbivore. There are strict rules governing carnivore behavior toward their herbivore classmates. Legoshi is a huge grey wolf, skittish and self-effacing. Other students including Bill the tiger and Louis the red deer are trying to get him to come to terms with the nature he tries so hard to sublimate.

Also, the book opens with the mysterious murder of Legoshi's friend Tem, an alpaca.

The Man Who Came Down The Attic Stairs

by Celine Loup

48 pages

Published by Archaia

ISBN: 1684153522 (Amazon)

[spoilers] This is psychological horror featuring postpartum psychosis. I don't know whether the horrors contained are plausible or if it's just pop horror using the psychosis label as a crutch (as was common in '80s/'90s psychological horror).

In any case, the art and atmosphere are gorgeous. Loup's illustration chops are top notch, and the use of SFX lettering piercingly good.

442

by Koji Steven Sakai, Phinneas Kiyomura, and Rob Sato

80 pages

Published by Little Nalu

ISBN: 0692156763 (Amazon)

The 442nd Infantry Regiment was a US Army regiment composed almost entirely of second-gen Japanese American soldiers, many of whom came (as a declaration of loyalty) out of the concentration camps that had sprung up in the US. 442 focuses on a particular soldier's experiences as a member of the 442nd in the Battle Of Vosges.

While you don't want to pit books against each other, it's unfortunate that 442 released in the same year as George Takei's They Called Us Enemy, because while Takei's book is the lesser of the two, it pretty much entirely overshadowed 442. Sakai, Kiyomura, and Sato's book uses unconventional paneling and blended flashbacks in a beautiful way to heighten the turmoil being felt in the midst of military service for a country that doesn't value the individuals being thrown into the grinder. Where They Called Us Enemy is mostly useful as an educational tool to introduce young readers to the fact of the concentration camps in the US, 442 is a work of literary art in its own right and will satisfy readers already acquainted with the terrors the US wrought against its own people.

Major Impossible

by Nathan Hale

128 pages

Published by Harry N. Abrams

ISBN: 1419737082 (Amazon)

Major Wesley Powell, fresh from the terrors of the Civil War, was the first to chart the path and elevations of the Grand Canyon in an expedition fraught with peril, underwear, and huge fires. And as per usual with Nathan Hale's Hazardous Tales, not everyone lived. Still, author Hale keeps things moving and humourous as he tells his ninth story of crazy stuff from American history.

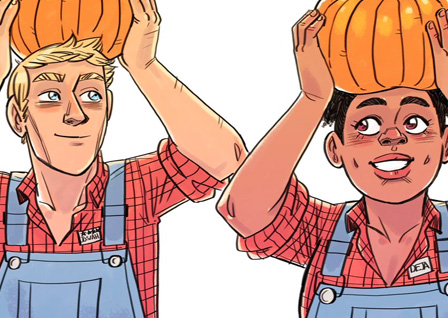

Pumpkinheads

by Rainbow Rowell and Faith Erin Hicks (colored by Sarah Stern)

224 pages

Published by First Second

ISBN: 1626721629 (Amazon)

Pumpkinheads is a fun, frisky rom-com. Rowell writes something like a cross between Can't Hardly Wait and Before Sunset (only with more madcap shenanigans). It's a book that's light but one that satisfies.

Hilda And The Mountain King

by Luke Pearson

80 pages

Published by Nobrow

ISBN: 1911171178 (Amazon)

Wrapping up the Hilda series, Pearson brings us full-circle from the troll-centric story of Hildafolk, finally bridging the gulf between countryside and city. It's a good book but tightly packed, and doesn't breathe as much as that first book did. (In fact, this might be why I prefer that first story to the later entries.)

Simon & Louise

by Max de Radiguès (translated by Aleshia Jensen)

120 pages

Published by Conundrum

ISBN: 1772620351 (Amazon)

Simon & Lousie is two stories (one Simon's and one Louise's) that end up being the same story. It's young love and young loss, and was a pleasant read. And it's always nice to see how seeing the other side of things can dramatically shift perception of an event.

Cleopatra In Space

by Mike Maihack

6 vols

Published by Graphix

ISBN: 1338204122 (Amazon)

With the penultimate volume of the adventure series for young readers, Maihack leaves everything in a shambles for his characters. Beset by big betrayals and the collapse of their safe spaces, Cleopatra and her friends are in place to fight their final battle against Octavian. Vol 5 has a nice section in its opening telling the story of Cleopatra's best friend Gozi and how he fared in Cleopatra's absence after she was mysterious drawn into the future.

Happiness

by Shuzo Oshimi (translated by Kevin Gifford)

10 vols

Published by Kodansha

ISBN: 1632363631 (Amazon)

Happiness grew more and more disgusting as it went. It moved from fun pop horror into the nauseatingly grotesque. And the vampires turned out to be the least horrifying aspect of the story. Honestly, I should have expected this kind of narrative subversion from Oshimi. (I've yet to read one of his books that remained the kind of story he began it to be.)

After the crescendo of abominations in vol 9, the tenth and final book in the series operates as a slow release of held breath. It begins with a very abrubt climax to the series and then follows with a long, relaxed epilogue—one that was enjoyable enough that I could almost forgive Oshimi for putting me through vols 7 through 9.

Fangs

by Sarah Andersen

Published online

Fangs is about a vampire dating a werewolf. Fangs is funny. Sometimes really funny. Also, it's by Sarah Andersen, the artist of Sarah's Scribbles. This was surprising to me because while Scribbles is rough, crunchy, and cartoony, Fangs is beautifully illustrated, making Scribbles an aesthetic choice. Whatever. Fangs is a hoot and really neat looking.

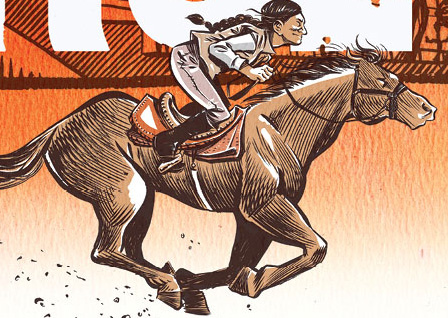

Grand Theft Horse

by G. Neri and Corban Wilkin

240 pages

Published by Lee & Low

ISBN: 1620148552 (Amazon)

Well-paced story about Gail Ruffu, who absconded with a race horse she trained and part-owned after she saw how badly it was being abused. It's a wild story that is almost more about a crappy lawyer than it is about the horse.

This Land Is My Land

by Andy Warner Sophie Louise Dam

160 pages

Published by Chronicle Books

ISBN: 1452170185 (Amazon)

Similar in structure to last year's Brazen, Warner and Dam's book takes a handful of pages each to summarize the history and circumstance of a thirty unique micronations, utopias, and self-made states. The chapters fall into five categories: intentional communities, micronations, failed utopias, visionary environments, and strange dreams. Some of these are bizarre, some are noble and interesting, and some are a hoot-and-a-holler. In all cases though, fascinating projects that just might inspire you to declare your own nation-state :)

Maiden Railways

by Asumiko Nakamura (translated by Jocelyne Allen, lettered by Nicole Dochych)

218 pages

Published by Denpa

ISBN: 1634429184 (Amazon)

We need more train-otaku writing rom-com stories focused on trains and the stations they pass through. I picked this up on the strength of Nakamura's luscious noir-esque mystery Utsubora, and while the genre and content was entirely different, I wasn't the least disappointed. These stories are light, breezy, and enjoyable. Good wholesome romance, with each story focusing on a different aspect of the the human interchange. (As with probably most readers, my favourite story was the one about the guy who discovers a hidden den of model train enthusiasts—which honestly should be enough to sell you on the book.)

Kingdom

by Jon McNaught

128 pages

Published by Nobrow

ISBN: 1910620246 (Amazon)

Kingdom could also probably be titled Scott McCloud's Aspect-To-Aspect: The Book. It's huge pages are absolutely clogged with tiny panels that take the reader on a tour of every single setting the book's characters inhabit. It's glorious in its way.

I was not so enthusiatic about my time spent with those characters, however. Kingdom tells the story of a mom and her two children, spending a holiday at a sad tourist village that she remembers from her childhood. We see a location worn down inhabited by people who are worn down in a world that is worn down. It's either a cynical book or a realist book. Really, these people and places feel like how I often feel. Their joys and indulgences are small, often petty, and their interactions with each other miss out distinctly on the wonder that human interaction is absolutely fraught with. The wonder is there, just unnoticed. (Or maybe just undernoticed.)

It's welld-one in that I felt like McNaught was lecturing me by simply letting me observe what I hope I am not like but very often may be. In the parlance of too many: I feel seen.

Guts

by Raina Telgemeier

224 pages

Published by Graphix

ISBN: 0545852501 (Amazon)

The third in Raina Telgemeier's autobio comics runs apace with the other two. Young readers, especially fans of the other two, are going to enjoy (and hopefully learn from) Telgemeier's discussion of anxiety and how she struggled to manage it as a kid. It's not my daughter's favourite book, but she is happy to own a copy on her shelf, and both of us would happily recommend it to other children.

They Called Us Enemy

by George Takei, Justin Eisinger, Steven Scott, and Harmony Becker

208 pages

Published by Top Shelf

ISBN: 1603094504 (Amazon)

The real power in They Called Us Enemy is that Takei is telling us the story of his own experience in the concentration camps that the US, in a fit of racist terror, set up for Japanese residents in America (not citizens, because we did not allow Japanese to become citizens by that time). The art was a disappointment to me, especially comparing with Harmony Becker's other work—I presume deadline and budget had a lot to do with that.

The chief value for They Called Us Enemy is going to be in introducing young readers to one of the great horrors that haunts the historical closet of The Land Of The Free. (I wish it were the only one.) I hope that Takei's popularity will help get this book into school libraries across the nation, because the government-approved codified racism in the midst of the "golden age" of American history should always be remembered.

For The Kid I Saw In My Dreams

by Kei Sanbe (translated by Sheldon Drzka, lettered by Abigail Blackman)

3+ vols

Published by Yen Press

ISBN: 1975328868 (Amazon)

This new murder-mysterious work from the creator of Erased boasts another supernatural twist but so far is quite a bit more mundane. Still, it'll be interesting to see how this one pans out. Still too early to tell if it'll be as great a thriller as Erased.

To Your Eternity

by Yoshitoki Oima (translated by , lettered by)

12+ vols

Published by Kodansha

ISBN: 1632365715 (Amazon)

To Your Eternity readthrough tweet thread

To Your Eternity is such a strange book. It never really gives you a place to hang your hat. It covers ten thousands of years, and different arcs feel like different genres. After concluding a long war-arc, its now jumped up to the present day and features shonen-esque highschool stuff. Still, it's a beautifully drawn book with an ambitious scope and curious to see where Oima will take us.

Off Season

by James Sturm

216 pages

Published by Drawn & Quarterly

ISBN: 1770463313 (Amazon)

Oh gosh. What to say about this? Honestly, I read it about nine months ago and don't remember the specifics that well. While I thought it captured some of the political turmoil I've seen tearing at families I know in the advent of Trump's America, where I felt the strongest was in its portrayal of human relationships, how external pressures can take something warm and comfortable and either introduce or uncover prickly parts that break or bruise what we previously found reliable.

Hot Comb

by Ebony Flowers

184 pages

Published by Drawn & Quarterly

ISBN: 1770463488 (Amazon)

Whether one finds the drawings charming or too rudimentary, Flowers' stories are warm, heartfelt, and open. I'm a bit conflicted as I found most of Hot Comb's value to me personally was tied too tightly to my position as a tourist. It was an interesting book, certainly, but I worry that too much of that was due to how little interaction I have with black people in daily life. I live in a place where 40% of the population is white, 40% is Asian, and the other 20% a split between Latino and Middle-Eastern. A bare .5% of my area is black, so the stories and kinds of stories Flowers tells are understandably interesting to me as they represent a whole world that seems exotic by how foreign it is. This is good in its way as it tills ground to grow empathy and suppress presumption, but simultaneously I don't know how great the book is for those who are much more familiar with the kind of world Hot Comb represents.

Frogcatchers

by Jeff Lemire

112 pages

Published by Gallery 13

ISBN: 1982107375 (Amazon)

A surrealistic death's dream reflection on what matters, Frogcatchers is a short story visually extended across a hundred pages. It's not Lemire's most invgourating work, but it's always nice to see him doing stories hampered neither by science fiction tropes nor by corporate IP.

Qualification

by David Heatly

416 pages

Published by Pantheon

ISBN: 0375425403 (Amazon)

An autobio comic in which Heatly describes his Fight-club-esque addiction to support groups. It's an engaging work and one can only admire the fortitude of Heatly's wife.

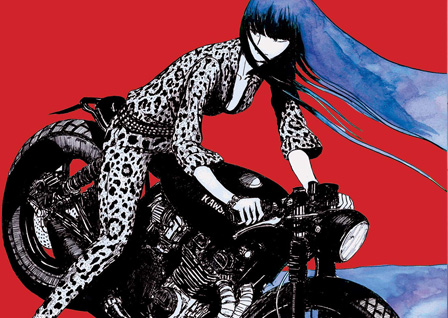

Ryuko

by Eldo Yoshimizu

2 vols

Published by Titan

ISBN: 1787730948 (Amazon)

Ryuko is a book with tramendous art but fluff content. If you're looking for an interesting or meaningful story, you should probably move along, but if you're up for some of the most dynamic and starkly exciting art around, you've found a home here.

1–1011–2021–3031–4041–5051–6061–70

Want to support me?

There are basically a couple ways to support me, if that's something that sounds fun or valuable to you.

1) Through Patreon.

2) Through buying my stuff. I've got an etsy shop to sell comics, books, and prints.

Navel Gazing

Coming up with a ranked list of things for a personal site or post on Facebook is entirely different in nature from ordering things for a Serious Critical Outlet (which I vaguely pretend to be). I can't just post What I Liked because 1) I have a site mission to consider and 2) for the list to be recognized as worthwhile to most readers, it has to contain enough of those things that other people would list to seem legit.

And while I never cheer on popular books that I hate just for the concept of earning legitimacy, there's always a bit of artificial list reorganization that is maybe even subconsciously designed to appeal to a readership. And maybe I'll even bump up a smallpress indie book that you can't even buy because Man that makes it feel like I'm serious about comics and you should trust me. (By the way, I *am* serious about comics and you definitely *should* trust me.) But maybe I won't do that. Most of these motivations are present but subconscious.

Does the fact that I'm on friendly terms with some creators give those books a bump? I don't see how it couldn't, even if I'm not conscious of it happening. When you read a good book by a stranger, you think, "Hey that was good!" When you read a good book by a friend, your naturally warm feeling for that other person blends with your experience of the book (because nothing social occurs in a vaccum) and now you think, "Man, that was a good book! I loved it!" And of course friendship also tends to soften criticism as well. Because we're not robots, you and I.

Also, I have to balance in some sort of subjective rubric for valuating a) What I liked with b) What is valuable and c) What is high in craft-quality. Every year, I find creating the list more daunting and more frustrating. Especially since not only is #26 not substantially "better" than #27 but also #26 is likely not substantially better than #45. I mean, it's a good problem to have. Lots of good books to read. And more every year. Essentially, we will never run out of good comics to read. It's like a golden age or something.

Good Ok Bad features reviews of comics, graphic novels, manga, et cetera using a rare and auspicious three-star rating system. Point systems are notoriously fiddly, so here it's been pared down to three simple possibilities:

3 Stars = Good

2 Stars = Ok

1 Star = Bad

I am Seth T. Hahne and these are my reviews.

Browse Reviews By

Other Features

- Best Books of the Year:

- Top 50 of 2024

- Top 50 of 2023

- Top 100 of 2020-22

- Top 75 of 2019

- Top 50 of 2018

- Top 75 of 2017

- Top 75 of 2016

- Top 75 of 2015

- Top 75 of 2014

- Top 35 of 2013

- Top 25 of 2012

- Top 10 of 2011

- Popular Sections:

- All-Time Top 500

- All the Boardgames I've Played

- All the Anime Series I've Seen

- All the Animated Films I've Seen

- Top 75 by Female Creators

- Kids Recommendations

- What I Read: A Reading Log

- Other Features:

- Bookclub Study Guides