Yamada-Kun and the Seven Witches

So before we actually get to talking about Yamada-Kun and the Seven Witches directly, let's talk about what I personally think of as a fruitful way to engage books that contain ideas, themes, or presentations you find repulsive or harmful or maybe even just not to your taste.

It's possible that only four of these characters are even in the book.

It's possible that only four of these characters are even in the book.

One of the interesting things about living in a pluralistic society (and honestly, these days, in a global society) is that we are heteronomous but still making at least some attempt at social harmony. In any collection of people, you're going to find a variety of opinions on a variety of issues. At my day job, we are about ten people and all roughly concerned with the same goal—yet we are politically and social diverse, often strongly disagreeing on what may be important issues (their Facebook posts may even sometimes drive me a bit crazy). And that's just ten of us, from similar backgrounds in similar contexts. Expand that out to the wide world and you've got a myriad of ideas and beliefs and interests and histories, none of which can perfectly cohere.

I know people who think gun ownership is morally bad and I know people who think prohibiting gun ownership is morally bad. I know people who think being queer is morally bad and I know people who think that thinking being queer is morally bad is itself morally bad. I know people who think being a socialist is morally bad and those who think being a capitalist is morally bad. Republicans, democrats. Pro-life, pro-choice. Pro-vaxx, anti-vaxx. Ethics in gaming journalism, ethics in gaming society. And those are the blunt-force, overt, and simplistic issues.

The fact of the matter is: if you read books at all, you are going to encounter things that you disagree with, things that you may even find repellent—because books are written by people who are not you. So really, there are a couple ways of interacting with books: judge them for what they are (voices from distant souls) or judge them for how well they cooperate with what you believe.

And as much as I'd like to say, Sure, well obviously the responsible reader will go the former route, it's of course not as simple as that. Every one of us is happily imprisoned by our subjectivity—by the biases that consciously or unconsciously form who we are, who we display ourselves to be, and what artistic expressions we will ally ourselves with. Still, it's something to keep in mind—and maybe intentionally trying to remain aware will make us better readers and better members of a society trying to strive toward harmony while simultaneously doing its best to self-combust.

So then, what is my reaction to and interaction with a text in which the affable heroine expresses some form of fill-in-the-blank-thing-I'm-offended-by? I like this question—mostly because it lets me talk about books and why books are rad and why reading broadly and widely is one of the most powerful experiences in the human experience.

So here it is, nutshell-like: we donít read literature to see ourselves; instead, we read to see humanity.

There was a point at which I started noticing that I was better able to care about people, that I was better prepared to see the world from their shoes. It had to do with books and the fact that I was consuming not just lots of them, but that I was picking from a wide variety of sources and backgrounds. There was a recent study on empathy and itís backed up what Iíve been saying about myself for years:

Reading literature builds empathy.

In the space of a well-written book well-read, I am able to inhabit the mindset and decisions of a person who is not me, a person I will never in my life be. Their background, thoughts, beliefs, and life choices are not mine. For the amateur reader, these Being-John-Malkovichian episodes can be entirely discomforting, and the initial reaction for many is to rebel against the notion—to become upset that a character (or author) might not make the same decisions that you might believe yourself to make in similar situations.

Every book is an exercise in perspectivalism, in empathetic psychology. Every book is an opportunity to learn a little bit more about the human condition we all strive in. Every book is an opportunity to better learn to love oneís neighbour as oneself.

So when I read a book in which a protagonist overeats, takes a life conflictedly (or even unjustly), displays a distasteful and perhaps socially harmful view of women, supports Zionism, steals a pie from a window sill to curb their child's starvation, browses the internet all day instead of working, doesnít believe in the same God I do, robs a bank, says something I think naive or stupid or hateful about immigration or about the poor or about blacks or about international policy—when I read those books, I absolutely do not overlook those things. Besides those things being essential to stories generally, I donít see what the point would be. These are human things and things that humans do. If the goal of reading is to engage the human condition, then I am defeating books and their purpose if I turn my head away and tut-tut while skimming over to the parts that are less human.

And if I am defeating books, then in a very real sense, I am defeating myself. I am rendering myself incapable of growth. I am abandoning my soul-health to myopicism. Books are a conversation between the reader and the whole world—and when that conversation ends, the reader loses. (The world loses too, but Iím primarily concerned about the reader here.)

So when I read a book and encounter someone I don't like (or someone I do like but who does something I don't like), I relish the opportunity to get to know her. She is not real in the sense that she is corporeal, but she is real in that she was composed in the mind and of the beliefs, experiences, and imagination of a very corporeal person. In reading her story, I am having a conversation with the lives and beliefs and imaginations of her creator. What will I learn from this character? How will learning from her inform my world? How will the consolidated experiences of coming to better understand people who are not me translate into the way I live? How will the book improve me? This is the delicious proposition of reading literature.

It can be scary, maybe, to be confronted with that with which you disagree, that which is unknown to you, that which may even repulse you. But thatís part of the process. Every good book is an opportunity to improve oneself—and in improving oneself, you improve society (even if only by a smidgen).

The risk readers run at this point is that we turn all reading into pedagogy, into a chance to learn. And while certainly every book is an opportunity to enlarge our sense of the human endeavor, we cannot pretend that there should be no sense of enjoyment in books. Even books whose characters or expressions are not ones we approve of.

While I can nearly guarantee that almost no one read McCarthyís The Road to be entertained in any sort of facile way, almost no one probably read hoping that they would find no sense of satisfaction in the book. Entertainment need not be merely understood as that kind of rush of jubilation we might experience when we first saw the Death Star explode or watched Clint Eastwood fool Eli Wallach again and again. Entertainment can include any number of nuanced reactions to a piece. Maybe it's the sense of poignant loss when Rick lets Ilsa fly away to America. Maybe it's listening to the snappy banter in A Philadelphia Story. Maybe it's hearing Harry Lime explain cuckoo clocks and Borges to Holly Martin. Maybe it's watching two kids with cancer cheering and mourning each other through the valley of the shadow. Entertainment can be a lot of deeply held and deeply important things. And it can be found in so many various corners of a work (which is why I might adore Snow Falling on Cedars while you found it boring—I just found a corner to enjoy that remained undiscovered or uninteresting to you). We diminish entertainment when we think of it only in its dumbest sense.

There is a lot of mutual investigation of bits and pieces in this book.

There is a lot of mutual investigation of bits and pieces in this book.

All this has been a bit circuitous, but the short version is that we can find legitimate value and legitimate entertainment in stories that may repulse us in one way or another—and that we each have to investigate how we will personally interact with books containing things we find hurtful or harmful.11A great exercise in self-examination is to ask yourself which of all the things you think are bad are the things that will turn you off from a book. And then ask yourself why that is the case.

I remember reading some critiques of Bill Willingham's Fables. One strongly objected to the series based on a view Bigby Wolf expressed in regard to Israel's international policy of violent retaliation. I personally also did not agree with Bigby's praise of Israel's foreign policy, but I was curious about the reason why Israeli foreign policy was the tipping point for that particular reviewer. Why not the laissez-faire attitude in the book toward killing? I doubt the reviewer is actually comfortable with casual threats of murder and casual, expeditious killing, but none of those things were brought up as reasons not to like Fables.

It's fine to be turned off by one thing we don't like and not by another thing we don't like, but we should always be game to ask ourselves Why.

All of this comes back to Yamada-Kun and the Seven Witches in that it does this thing common to too much of the manga I've read aimed at a youthful male audience. It capitalizes on sex as titillation, as base entertainment. It sexually objectifies women (teenage women) and employs sexual harassment as a source of light humour. I talked a bit about this when I reviewed Ken Akamatsu's Negima, and while Yamada-Kun is pretty near amateur hour by comparison, it's still wildly distasteful and something I don't feel I can remotely condone. It may even contribute to negative or at least unhealthful beliefs about women and their place and purpose in the world. (All this despite the author being herself female.) In those moments, I found Yamada-Kun repellent, sometimes vile, and at the least problematic. Still, for all that, I'm very much enjoying the series and find it often highly entertaining.

. . .

. . .

Because things can, and often are, more than a single thing simultaneously. Especially when they're sprawling narratives with fistfuls of unique characters.

Yamada-Kun didn't seem like the kind of book I'd ever give a chance, let alone one I'd come to love. The premise is ridiculous and tailor-made for showcasing all the kind of sexual-harassment-as-humour moments I rather abhor. Ryu Yamada discovers he has the ability to copy the powers of the various witches at his school by kissing them. He can also exert those copied powers over others by kissing them. Lots of kissing, some of it even consensual. Some of the powers include body-switching (which inevitably involves self-investigation of one's new flesh), mind-control (removal of character agency is always a bit sketchy), and a charm power that causes those under the spell to fall hopelessly in love with the caster. None of that sounded great to me, but 180 chapters were available to read on my Crunchyroll Manga app and I was home sick, so I thought I'd at least check it out.

Even within ten chapters I was already hooked. For all the moments I was rolling my eyes or sighing at the same-old has-been tropes, I found myself charmed by the more genuine moments and surprising plot turns the book would take. And even for all of the common things that I'd normally find so boring—cf Yamada pretty quickly obtaining a harem—the book subverts expectations enough that I didn't often feel I was reading a regurgitation of stories I'd read a decade ago.

In 180 chapters33The series is still ongoing weekly. Yamada-Kun has completed two story arcs. I think a third would be enough to wrap the series with a tidy bow, but unfortunately, popularity tends to draw these things out overlong (just like with American tv!). In any case, many of the twists and turns have been ingenious. Some of them have been the kinds of mundane Oh of course moments common to Willingham's resolutions in Fables, but a good number make you stop and think, Oh my, that was pretty clever! I love that kind of stuff.

He really, really isn't.

He really, really isn't.

But what I've enjoyed the most about Yamada-Kun is watching the book's single-minded approach to accommodating friendship develop. At core, relationship is what the book is all about, and while Yamada begins the book as an outcast and loner, creator Miki Yoshikawa seemingly will not rest until both Yamada is reconciled with everyone and everyone else is reconciled with each other. It's an entirely unrealistic vision, but Yoshikawa's focused dedication to the concept warms me.

Plus there's a cute romance bubbling throughout and I'm always a sucker for that sort of thing. Two lonely people finding fulfillment in each other and using that newfound confidence to bring light into the lives of others is a great little concept. It makes for an interesting dynamic because Yamada and his love interest each often sacrifice pieces of their own relationship for the good of others—which inevitably builds and strengthens their own relationship again.

Charmed, I'm sure.

Charmed, I'm sure.

Yamada-Kun is never going to be the kind of book that requires a lot of thought. It doesn't deal with ideologies or life-consequences or moral quandaries in a way that encourages readers to pause and consider. It doesn't seem to have much of an agenda apart from being a fun way to engage the idea of friendship. And that's okay. I enjoyed it for what it is—despite all the parts that I didn't enjoy.

A Note on Sex as Humour

Nearly 4000 pages of comics is a lot. That's how much Yamada-Kun I read over the weekend. And somewhere in there, I began to wonder about all the sexual humour—the boob jokes and the panty shots and the accidental co-ed baths. Did those things actually contribute to the overall happy-go-lucky vibe of the book? Would the book survive having those parts and characters stripped from the work or subdued?

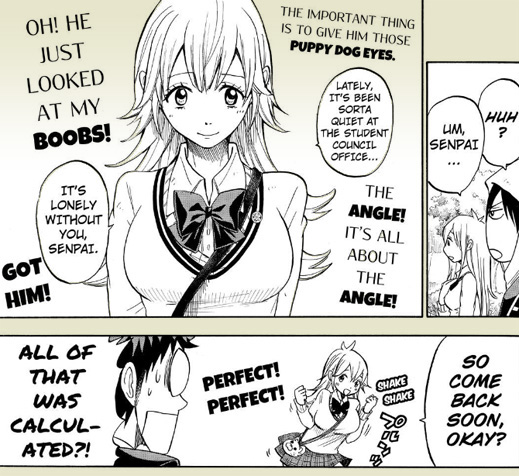

In this scene, Yamada reads the mind of the ditzy, large-breasted blonde—who proves that she is not ditzy at all but attempting to manipulate men through her physical assets and demeanor.

In this scene, Yamada reads the mind of the ditzy, large-breasted blonde—who proves that she is not ditzy at all but attempting to manipulate men through her physical assets and demeanor.

I thought about The Three Stooges. Not everybody finds them amusing,44I mostly do, but that's beside the point. but among those who do, I'm sure almost zero would find the cacophony of violence they employ to be fun if expressed in the real world. Not only would true victims of their antics be killed or blinded or hobbled or brain-damaged, but we don't at all believe their method of interacting to be appropriate in a real-world setting. But these kinds of pratfalls have a long history of being used in film and television to lighten a work, to keep it from being too serious. What if, I wonder, there's some legitimate use of fan-service in some similar manner? What if, like with The Three Stooges, we don't have to approve of the actual expression to find good-hearted humour in the fantasy version of it employed in our stories?

I don't actually know the answer to that. I'm just trying it on for size.

Good Ok Bad features reviews of comics, graphic novels, manga, et cetera using a rare and auspicious three-star rating system. Point systems are notoriously fiddly, so here it's been pared down to three simple possibilities:

3 Stars = Good

2 Stars = Ok

1 Star = Bad

I am Seth T. Hahne and these are my reviews.

Browse Reviews By

Other Features

- Best Books of the Year:

- Top 50 of 2024

- Top 50 of 2023

- Top 100 of 2020-22

- Top 75 of 2019

- Top 50 of 2018

- Top 75 of 2017

- Top 75 of 2016

- Top 75 of 2015

- Top 75 of 2014

- Top 35 of 2013

- Top 25 of 2012

- Top 10 of 2011

- Popular Sections:

- All-Time Top 500

- All the Boardgames I've Played

- All the Anime Series I've Seen

- All the Animated Films I've Seen

- Top 75 by Female Creators

- Kids Recommendations

- What I Read: A Reading Log

- Other Features:

- Bookclub Study Guides