Wandering Son

I was in elementary school in 1980 and in high school in 1990. I predated by a few years the rather briskly paced evolution of alt sexualities from something horrifying to kids to something that kids could dabble in without too much fear of ostracizing. I grew up in a town whose homosexuals-per-capita population was second in the state behind San Francisco. We were all pretty well aware of how common open homosexual lifestyles were in the town. We knew about the Little Shrimp. We knew about Sneaky Pete's. We knew about the Different Drummer bookshop. And yet, for all that, "homo" and "fag" were still slurs, and when a rumour spread in junior high that this one guy was playing pocket pinball in class, the whole school took it upon themselves to brand him as gay and therefore worthy of a derision that remained probably all the way through high school for the poor guy. We were all little bastards and didn't really have the cultural wherewithal to learn any differently. There certainly wasn't an internet out there to help us empathize with different people's stories about being different. Even when some of us turned out to be different in the ways we previously derided.

I'm not sure that having a book like Wandering Son would have helped when I was a kid, but it wouldn't have hurt, I don't think. At worst I would have written it off as gross—but even so, I would have seen another perspective. One I wouldn't see for nearly a decade more.

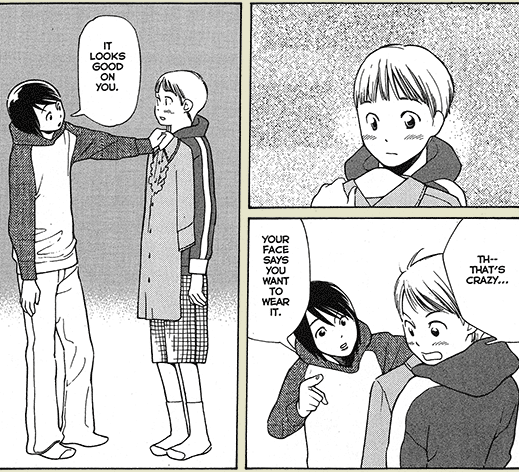

That's the trouble with girls

That's the trouble with girls

Story time. In a gathering of high school kids for some event or other, there was a game in which people would have to perform some stunt of the leader's choosing. One of them was to speak in a gay lisp. Five-sixths of the guys involved wouldn't participate—not because it was insensitive and othering—but because it was too gross. A friend of mine took a trip to Africa and this tribe's chief took his hand, wanting to show him the village. My friend shook off that man's hand. Fifteen years later he is still proud of that decision. In high school, at a school in the center of the second gayest town in California, there was a boy who tried out for the cheerleading squad. He was immediately deemed gay. I don't even know if he ever wore a cheer skirt or if he wanted to. Of course that wouldn't have had anything to do with his sexual preferences—we wouldn't have known that—but at least within the scope of our warped cultural pericope, that would have been slim justification for our prejudice. As it was, the mere hint of peculiarity in terms of sex or gender presumptions was enough to send us all into a whirlwind of confusion and antipathy.

Again, I'm not sure that having read Wandering Son would have helped, but it very well may have. Anything that humanizes the targets of othering is worthwhile because empathizing with those who are Not You and Not Like You is essential to loving them as you do yourself. And above everything else that it does so well, Wandering Son humanizes its characters—regardless of how much they deviate from the cultural norms their societies dictate.11Which should be easy, right? Because these characters are human. Really, we shouldn't even need a book to make the effort, but even my own very narrow personal history demonstrates with force that we do need books to make the effort. When I first approached Wandering Son I was concerned that, like so many works that have lessons to impart, it would come off as didactic and proselytizing. Instead, we have this warm-hearted, gentle story about a collection of kids growing up. Wandering Son doesn't lay out any argument for the humanity of its characters who diverge from social expectation. It doesn't need to.

Pro-tip from a non-pro

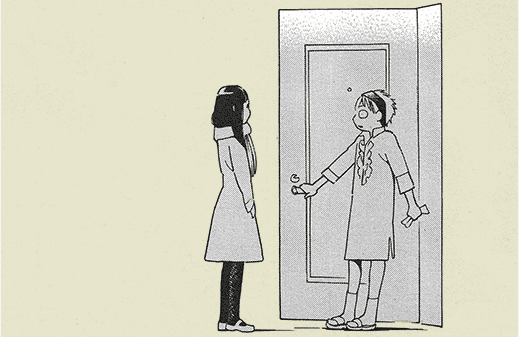

Pro-tip from a non-pro

don't answer the door in a dress if you don't want to be seen in a dress

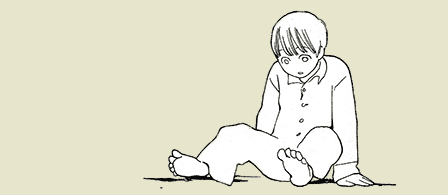

Takako's book allows you to grow comfortable with these kids as you would members of your own family. You see them happy; you see them hurt. You see their dreams; you see their fears. You see them reaching for lives that make sense to them, struggling even as we all do to find comfort and value in the things that attract our affections—all while trying desperately not to have our spirits crushed along the way.

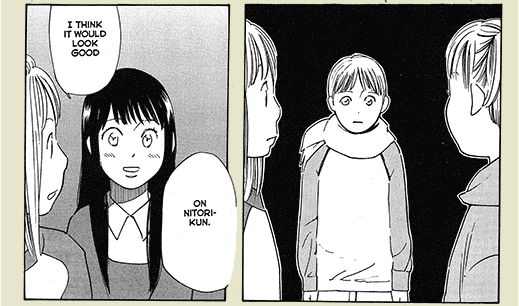

One thing I appreciated about Wandering Son is how neatly it eviscerates the presumption that transgressing gender distinction also necessarily informs sexual preferences. Growing up, it was the law of my land that transvestitism also meant homosexuality. A man who wore his wife's clothes in secret also obviously harboured a closeted homosexuality. A woman who dressed in man's attire22Granted, "men's attire" is a rapidly diminishing category of fashion. was giving off strong lesbian cues. Our understanding of the immutability of gender and its ties to sexuality offered us no room for understanding things in any other way. Wandering Son, by beginning its narrative journey in elementary school, removes sexual preference from the initial spectrum of topics—at least for the principal characters, if not for their peripheral antagonists (who engage in all the weak-minded slurs I would have ejaculated when I was their age). Series lead, Shu, a fifth-grade boy who gradually finds himself dressing more and more in girls' clothing does so wholly apart from any sexual interest. He simply enjoys looking like the archetypical young girl. So too with his opposite number, a girl named Takatsuki, who likes to dress as a male (which is easier for her to get away with, since male clothing is increasingly bi-sexual). In the first volume she begins her period, underscoring her sex despite her objection to normative gender cues, but has so far not had any opportunity to express her sexuality.33Honestly, when I was their age, I wanted so very badly to "hump" my crush into oblivion, but that was mostly just me going with social expectation. Though I bore affection for a girl, it wasn't really sexual, I don't think. For one, I was prepubescent. For another, I really only had the vaguest understanding of what "humping" included. I understood the reproductive aspect and I understood that I should want to do this thing, but I had no real libido and so no visceral understanding of how sexual desire actually worked. I had, instead, a stand-in for that desire that was constructed from expectation more than anything. 44Homosexuality does become topical later in the series.

While pretty clearly a book intending to explore the social issues involved in the gender/sex confluence of spectral anomalies—and one that so far as I can tell does a pretty stellar job at that investigation—Wandering Son is foremost an interesting story. I don't think it could possibly succeed at drawing out its social questions if it failed to present well-described human characters in largely believable55Not being Japanese, I don't really have any sense of how much verisimilitude with which Takako represents the Japanese reaction toward transvestitism and transgenderism and transsexualism. Translator Matt Thorn offers a brief essay on the subject in the backmatter of volume 2, but it's unsatisfyingly brief. In any case, the protagonists meet much less resistance in Wandering Son's story than I believe they would in the U.S. narrative circumstances. These characters move and speak in realistic, human ways. They aren't cartooned caricatures of pedagogical lances meant to joust with our presuppositions. They may actually do some of that jousting, but it's only because they are realized characters that they have any power to blossom empathy in our hearts.

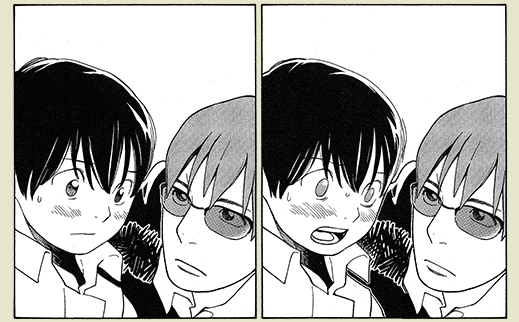

It can be tough being a freshly minted man...

It can be tough being a freshly minted man...

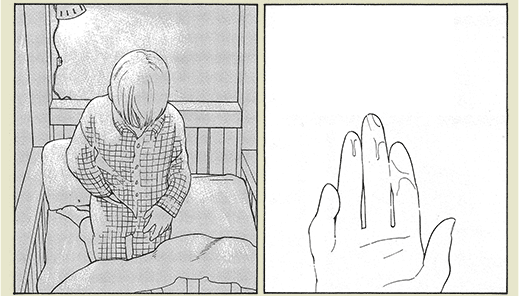

The art is rather lovely, the lines fine and bold. Takako employs a simple illustration style that provokes the reader to focus on characters, their expressions, and the way they carry themselves. The illustration of the book in every way serves the purpose of the story and its unadorned vitality both keeps the reader from distraction and invests characters with an immediacy that helps sell the illusion of their reality. Fantagraphics' production on the book gives the art plenty of room in which to luxuriate. The pages are large and the paper thick. For hardbacks, these volumes are surprisingly light. They are beautifully produced and will look handsome on a shelf. The only drawback is that considering their not-insubstantial size and the fact that there are currently fifteen volumes available in Japan, these will easily take up a whole shelf in many bookcases (and of course, for fans with plenty of space to grow, this might not be a bad thing).

In a year of some fantastic books, Wandering Son continues to shine and is easily recommendable. It can be a handy introduction to a different kind of experience for those who come from generations with more ossified social beliefs (such as my own generation); and it can function as a great segue for parents to begin discussing social/sexual issues with their children. Complex moral structures treated with humanity and care is one of my favourite hallmarks of good literature—and in case you hadn't guessed, I'd happily deposit Wandering Son in the category of Good Comics Literature.

Good Ok Bad features reviews of comics, graphic novels, manga, et cetera using a rare and auspicious three-star rating system. Point systems are notoriously fiddly, so here it's been pared down to three simple possibilities:

3 Stars = Good

2 Stars = Ok

1 Star = Bad

I am Seth T. Hahne and these are my reviews.

Browse Reviews By

Other Features

- Best Books of the Year:

- Top 50 of 2024

- Top 50 of 2023

- Top 100 of 2020-22

- Top 75 of 2019

- Top 50 of 2018

- Top 75 of 2017

- Top 75 of 2016

- Top 75 of 2015

- Top 75 of 2014

- Top 35 of 2013

- Top 25 of 2012

- Top 10 of 2011

- Popular Sections:

- All-Time Top 500

- All the Boardgames I've Played

- All the Anime Series I've Seen

- All the Animated Films I've Seen

- Top 75 by Female Creators

- Kids Recommendations

- What I Read: A Reading Log

- Other Features:

- Bookclub Study Guides