The Underwater Welder

Memory is a beast, savage and merciless. It bites and tears and conquers. Its armory storehouse is not filled with inconsequentialities but with the things that stick—with barbs and teeth and talons more often than not. Certainly memory can be a rewarder, but only capriciously so.

Do I remember my first kiss? I do. But not in the fidelity of colour and texture and temperature and tone that such a moment should deserve. Do I remember where things went wrong with that girl, so long ago? I do. And often in tantalizing, horrible detail. Do I remember where things went wrong with the next girl and the next? I do and I do. Scars, as it turns out, are more indelible than comfortable massages.

Do I remember when my daughter was born? A little. More that it happened and that I was there than any sense of real presence. Do I remember my son being born? Not really. But I do remember, vividly, the first time my daughter fell down a flight of stairs, when she had a terrifying experience with croup, when she hit her head hard and stopped breathing. I do remember saving her with a split-second to spare from a rogue tide shift when she was only one. The things that break your heart are the things that build you for they are the things that remain strongest in your memory.

And if memory has one single weapon with which it eviscerates the soul more gleefully, heartlessly, and permanently, that tool of destruction is surely regret. And it is against that particular blade that Jack Joseph struggles. He may not yet have put a name to the thing that is killing him, destroying his life, and leaving his personal society and civilization a derelict wasteland—but a deep regret (and its companion sense of guilt) is Jack's enemy, whether subconscious or not.

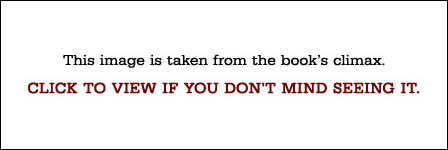

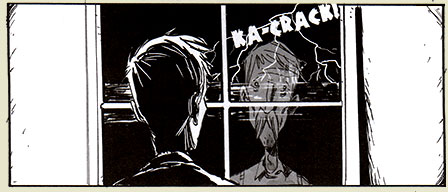

Jeff Lemire, as he has in Essex County, continues to explore the lives of broken people—people to whom life's treacherous circumstances have paid particular attention. In exploring Joseph's life, times, and other times, Lemire uses a mix of pages defined either by the strict and straightforward promise of black-and-white, cut-and-dried art or by dreamy, less-defined and less-defining water-diluted ink washes. The stark positives and negatives of the former are the ground on which The Underwater Welder's present day unfolds. This reality seems unshakeable and intentionally closed to interpretation and reinterpretation. The hazy, low-contrast mist that colludes with Lemire's usually strong-lined art is used strictly11There is one notable exception to this (spoiler): In the finale, after Jack has his undersea reunion with his father, finds the watch, and is rescued, Lemire doesn't return to stark black-and-white but instead remains in ink-wash mode—which lends strongly to the idea that Jack hasn't actually returned to the real world. That he somehow remains in another world, in the perhaps-afterlife catharsis-land he entered when he abandoned his labouring wife to look for a watch. in narrative sections that cross the boundaries of the real, whether through memories or through imagination or through the imposition of some sort of world of magic and mystery that runs parallel our own. It's a good visual trick and works very well for a story that skips through all sorts of versions of What Is And Was.

Through his visual storytelling Lemire has crafted a pretty wonderful tale of how the mistakes of the past, even when forgotten, can rule the choices of the present. Jack, the titular welder, is governed (almost maniacally so) by the ghost of decisions made as a child. Decisions that, while certainly selfish and childish, would hold outcomes impossible to predict. These are the kinds of choices that none of us should feel guilt over, but rationality and memory have never held any tenderness toward each other. We live our lives feeling responsible for things beyond our control (and inexplicably feeling not-culpable for a host of things we ought to feel responsible for—a topic for another story perhaps). We are confused souls and far more delicate than we usually prefer to recognize—and as Lemire explores, we are not that super at dealing with the wounds that memory not only leaves to visibly scar but tends also to draw to our attentions.

And at this point, I will discuss the ending, so if you wish for a spoiler-free experience of The Underwater Welder, please skip down to the Notes section below.

Initially, I was disappointed in Lemire's conclusion to Jack's struggle with regret. It seemed too crisp, too easy, too pat. Unlike the rest of us, Jack was granted instant catharsis, a magical moment unearned and unendured. He gets what he wanted, an impossible forgiveness. And while it makes for exciting storytelling, it felt to me too hollow. I wanted a story that reflects my experience with the beast, with memory. I wanted to see what Lemire had to say as a reasonable, thinking artist of great works about how a man weighed down under the bondage of regret might resolve his struggle. And in the end, it seemed, his entire solution was that there is no solution save for the miraculous. I felt cheated in that Jack's story no longer bore any resemblance to our own stories—for the wronged dead do not rise to offer their unmerited forgiveness.

But then, I thought more about Lemire's ending and I thought that I perhaps got it wrong at first. That Jack's conclusion remains steadfastly a variety of grey washes prompts the reader to wonder whether Jack has had his instant catharsis after all. If he never does actually return to the real world, the reader is opened up to all kinds of interpretive joys. Did Jack die and the magic of his ending is some sort of afterlife healing? Did Jack somehow travel into a parallel existence—and remain, as that place would be his only chance for happiness and safety from his memories? This second look at The Underwater Welder's conclusion leaves a more satisfying taste. It feels less a cheat and more an acknowledgement of the brutality of regret. In that reading, Lemire doesn't answer any questions so much as he points out how unanswerable those questions would be.

And that is good enough for me.

Notes

While The Underwater Welder is a solid project, both beautifully drawn and written, there is some evidence of rushed production that slightly mars an otherwise wonderful work. There are, for instance, strange interruptions of obviously computer-created graphics into what are meant to look like traditional-media pages—and not just the annoyance of the book's occasional digital fonting for signs. As awkward as that always looks, I'm referring to digital artistic elements, such as the low-res leg, ear, and blanket/gown that occupy the foreground of page 218.

And whenever there is a smoke-like trail obscuring the background, it looks as if it were drawn with a mouse. Examples of this can be found on page 9 (as well as throughout) both in the cigarette smoke of panel 3 and in the trail of radio words snaking up the page.

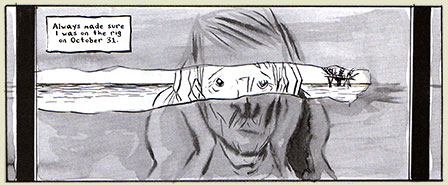

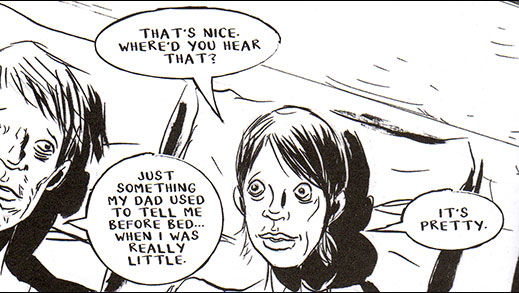

A lesser offense is that Lemire seems to have pretty small stock of word balloons (possibly even just one for dialogue and one for narration). He uses the same balloons throughout, only stretching them and rotating them as panels require it. It's not terrible and at least they seem to be vectored and well built to withstand the push-and-pull of resizing, but again, it makes it seem as if the project was rushed. Which is a pity when one considers how powerful Lemire's art can be.

These three word balloons feature the same art. The lower two have the same orientation but one is stretched vertically. The upper one is rotated. Sometimes they'll be mirrored, rotated, and stretched. Lemire gets creative, but I kind of wish he just drew each balloon.

These three word balloons feature the same art. The lower two have the same orientation but one is stretched vertically. The upper one is rotated. Sometimes they'll be mirrored, rotated, and stretched. Lemire gets creative, but I kind of wish he just drew each balloon.

Another issue is textual and should have, I think, been caught by an editor. On page 99, Jack narrates that he is the same age his dad was when Jack was born. On pages 164 and 191, Jack narrates that he is the same age as his dad was when his dad disappeared (his dad having disappeared when Jack was around ten). The conflict is obvious and could be read as a clue that Jack's grip on memory and reality are not firm, but as there don't seem to be other clues (so far as I noticed—to be fair, I'm not sometimes the most attentive reader) to direct us toward that line of thought, it seems more likely to read this as an error. In which case, more evidence of unfortunately rushed production.

Good Ok Bad features reviews of comics, graphic novels, manga, et cetera using a rare and auspicious three-star rating system. Point systems are notoriously fiddly, so here it's been pared down to three simple possibilities:

3 Stars = Good

2 Stars = Ok

1 Star = Bad

I am Seth T. Hahne and these are my reviews.

Browse Reviews By

Other Features

- Best Books of the Year:

- Top 50 of 2024

- Top 50 of 2023

- Top 100 of 2020-22

- Top 75 of 2019

- Top 50 of 2018

- Top 75 of 2017

- Top 75 of 2016

- Top 75 of 2015

- Top 75 of 2014

- Top 35 of 2013

- Top 25 of 2012

- Top 10 of 2011

- Popular Sections:

- All-Time Top 500

- All the Boardgames I've Played

- All the Anime Series I've Seen

- All the Animated Films I've Seen

- Top 75 by Female Creators

- Kids Recommendations

- What I Read: A Reading Log

- Other Features:

- Bookclub Study Guides