The Strange Tale of Panorama Island

I have never in my life seen an actual panorama. I'd love to, but I haven't. I'm sure most people living today haven't had the pleasure—as panoramas were largely popular in the 19th century and were already well on their way out by 1900. I have of course seen panoramic photography and the inheritor of the ill-fated Cinéorama, Disneyland's Circle-Vision 360°. Still, not the same thing and I regret that I will likely never have the opportunity to engage such staging and artistry in person. Reading about panoramas, while exciting the imagination to some small degree, really can't do justice to what must have been a tremendous thrill for 19th century viewers.

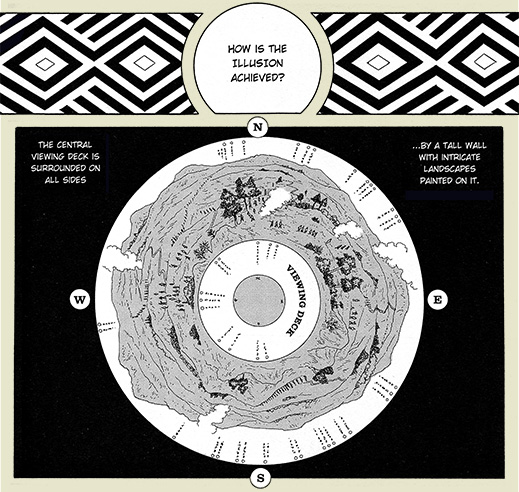

Panoramas were sometimes built of painted panels alone (often staged at differing depths to confer a sense of dimensionality), but many featured three-dimensional elements as well—sculpted pieces in the foreground designed to trick the mind into seeing depth where none existed. Observers were brought into an arena of specialized lighting and visual manipulation, which could then govern the rational mind into a particular aesthetic experience. The panoramic scene would elicit a mediation between beauty (a concept derived from sexuality) and the sublime (a kind of awe in the face of the horror of the unknown). This balance between the two was known as the picturesque.11Straight from Wikipedia: Thomas Gray wrote in 1765 of the Scottish Highlands, "The mountains are ecstatic. None but God know how to join so much beauty with so much horror." [sic]

Panoramas were means by which people could be theatrically transported into a world outside their own—a world of the picturesque, of beauty and awe conjoined. The panorama's chief conceit is that the viewer does not just take in a particularly lush painting but is installed within the painting itself. Canvas borders would be obscured by props such that the beginning and end of the panorama could not immediately be discerned. Having been enveloped within the panorama, the observer is made participant in the scene into which he or she has been placed—whether in landscape, cityscape, or the ferocious battles which dominated the later history of the artform.

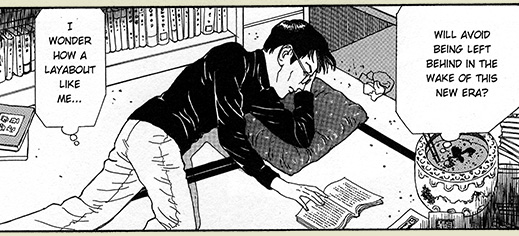

It is in multiple levels of panoramic engagement that Suehiro Maruo's adaptation of Edogawa Rampo's The Strange Tale of Panorama Island is concerned. The story's central figure Hitomi, a man of stolen identity, uses the wealth he acquires surreptitiously to fund the construction of some version of an earthly paradise.22Kind of like how I imagine Charles Foster Kane might have aimed in his own stately pleasure dome had there not been a Hays Code to hamper him. His goal is to submerge the book's characters in the titular island's vision. Through painstaking planning, skilled construction, a talented ensemble of actors, and wanton expenditures of seemingly endless wealth, Hitomi creates a lavish illusion—a living panorama into which guests (and himself especially) can experience an unreal world in a visceral way. Hitomi is centrally concerned that his fantasy island feel like a real experience—though one that is immediately picturesque, drawing together eroticism and natural awe almost seamlessly. Hitomi's strange and taled Panorama Island is an ode to hedonistic excess, a devotion to pleasure divorced from any context save for the immediate experience of that pleasure.

Interestingly, many of the critiques contemporary to the era of panoramic painting popularity are underscored and heightened through Hitomi's island. On top of the criticism that the easy illusionment of panorama experiences rendered them merely base propaganda, opposition at the time cited the operation of the locality paradox upon viewers. The locality paradox refers to observers' inability to discern their true place, whether they were in the locale presented in the panorama or in the viewing rotunda. Because Hitomi's goal is his guests' complete participation, he would not remotely see the locality paradox as problematic, but rather something desirable. Further criticism objected to the physicalization of the sublime. The Romantics feared that in rendering what ought to be awestriking from material compositions, the Wonderful would be reforged as Ordinary. While Hitomi would be likely to object to this, following his story through to its conclusion does offer evidence to support the Romantics.33In an entirely facile way, this makes sense. Here's a f'rinstance:

I grew up on the beach in Southern California. Almost literally. From age three through thirty-one, I lived within a short walk from the sand in Laguna Beach. Summers (and even falls and springs and a bit of winters) were spent on the sand and in the Pacific herself. Bare, tanned skin was everywhere. Bathing suits weren't particularly conservative and so seeing women with all but breasts and the nethers exposed was entirely normal. Common. Mundane. Even when I reached my teen years and was entrenched in a hormonally driven quest to surreptitiously take in the beauty of every girl I'd see, I never once considered bare shoulders, belly, or thighs to be any more magical than noses, knuckles, or elbows. When I discovered those from other American and international cultures considered otherwise, I was baffled. (An early, confusing lesson in multiculturalism—one that I wouldn't understand for a decade or more later.)

The point here is that what might have been considered mystical or awe-inspiring was robbed of that potential by its brute commonality. In other words, for a person raised in track housing, the idea of indoor plumbing isn't even something that merits thought. It's boring and a given and holds none of the magic that it would for someone from 1850.

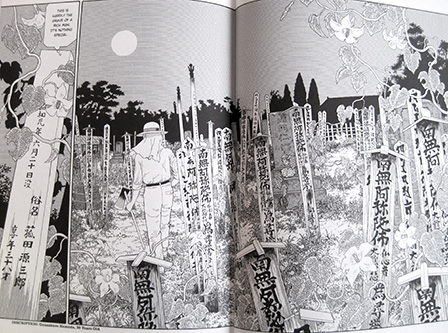

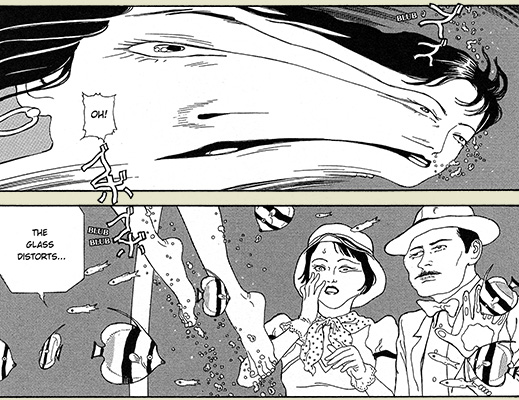

Additionally, more than Hitomi's goals even, The Strange Tale of Panorama Island does itself seemingly somewhat hope to draw even the reader into the panorama of the story.44Interestingly even the book's framework moves from horror (even if not necessarily sublimity) toward beauty, marrying the two concepts in a bifurcated sort of picturesque. Most literature attempts this to some degree, but Maruo revels so much in the visual spectacle afforded by the story's demands that one can't help but feel the forcefulness by which the artist presents both eroticism/beauty and horror/awe. Once Hitomi visits the near-complete island in the company of the woman with whom he pretends at marriage, the book shifts into a full-fledged attempt at propagandizing the wonders of the island. The artistic rendering of the island's decorations and landscapes is truly magnificent and sells prodigiously its paradisical lures. Maruo is an astonishingly talented illustrator when tackling the physical presence of the island, and some pages and panels may momentarily theft the artistically inclined reader of breath.55The artist is perhaps less equipped for the depiction of human persons—as faces (and especially the eyes) are often grotesque distortions beyond probability. I will admit that this may be an intentional stylistic bit and perhaps Maruo is making some artistic statement by giving everyone weird, lazy eyes. Like so:

In the end, as Citizen Kane-style utopian stories have taught us to expect, Hitomi's strange island becomes more Panopticon than Panorama. The reader sits centrally, observing all with unobstructed vision. Coinciding with the Romantic criticism, we find awe and beauty have been made cheap and so lose a bit of their magic. This is especially the case for Hitomi, who has lived longest and most abundantly the life within the panorama—he more than anyone is aware of the fabricated nature of the entire endeavor. By the strange tale's explosive conclusion, Hitomi seems rather spent, wearied, and bored by the whole thing. Perhaps this was Rampo and Maruo's intent, to propose a horror story in which the most unnerving thing is how easy it is to lose the verdancy of formerly wonderful things that arrive too easily. Perhaps they intend this as a statement on the value of struggle and rarity. Perhaps, in their way, they are Romantics themselves. Perhaps not, of course, but as within the panorama, what is seen is governed by one's context—so who's to say?

Good Ok Bad features reviews of comics, graphic novels, manga, et cetera using a rare and auspicious three-star rating system. Point systems are notoriously fiddly, so here it's been pared down to three simple possibilities:

3 Stars = Good

2 Stars = Ok

1 Star = Bad

I am Seth T. Hahne and these are my reviews.

Browse Reviews By

Other Features

- Best Books of the Year:

- Top 50 of 2024

- Top 50 of 2023

- Top 100 of 2020-22

- Top 75 of 2019

- Top 50 of 2018

- Top 75 of 2017

- Top 75 of 2016

- Top 75 of 2015

- Top 75 of 2014

- Top 35 of 2013

- Top 25 of 2012

- Top 10 of 2011

- Popular Sections:

- All-Time Top 500

- All the Boardgames I've Played

- All the Anime Series I've Seen

- All the Animated Films I've Seen

- Top 75 by Female Creators

- Kids Recommendations

- What I Read: A Reading Log

- Other Features:

- Bookclub Study Guides