Sin Titulo

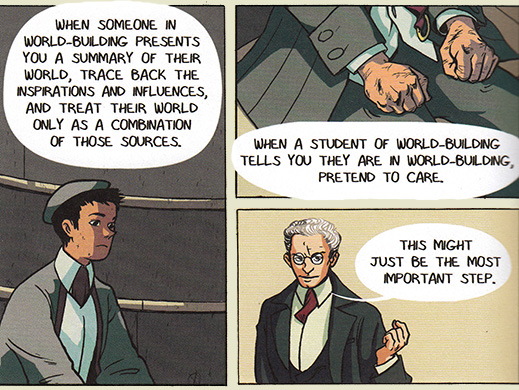

"When someone in World-Building presents you a summary of their world, trace back the inspirations and influences and treat their world only as a combination of those sources."

Panels from "Adel's Return" in Spera, vol 3

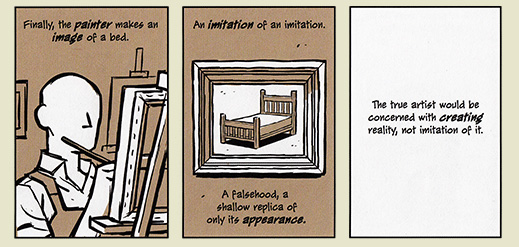

Panels from "Adel's Return" in Spera, vol 3

In the third volume of Josh Tierney's Spera, the author concludes with a short story, "Adel's Return," a bit of a coda in which Tierney (among other things) explores briefly the nature of the worlds we create versus those who would hope to diminish those worlds. His investigation develops via an in-narrative couple of high school classes, World-Building and World-Breaking (both introductory courses). World-Building is the province of the idealists and World-Breaking belongs to the cynics. World-Building is the whole output of the creative and imaginative self, in which a builder invests their lives and experiences, everything they are. World-Breaking is merely a set of tricks, illusions by which the cynic might chip away at the value of anything another creates. "Adel's Return" is a cool chapter in the middle of a cool series and flirts thematically with what I see going on in Cameron Stewart's Sin Titulo. Serendipitous that I read them in the same week then, right?

One of the things about worldbuilding we don't often recognize is that it's only tacitly the province of fantasy and sci-fi authors. Tolkien and Bradbury and Dick and Rowling and Martin are only showing us their amateur efforts in their novels. At the end of the day, a world you give a name is a world you've written off as one of your lesser creations. The real deals are those worlds that we continue to build and hone and craft across the landscape of our whole lives. We never think to name these because, really, what's in a name? A cheap taxonomy? A way of excluding all the glorious and vibrant details? A commodification of our imaginative selves? Genuine worldbuilding is the cosmos we create and recreate with every waking experience—and a good number of those that ricochet through the meat of our subconciouses, informing our dreams and learning from the same. Genuine worldbuilding is not Middle Earth or Hogwarts or Westeros or Earthsea or whichever other podunk barely realized fantasy realm we're so fond of. The real-deal worldbuilding takes place in every moment in the heads of every person across the globe. Billions and billions of worlds being constructed by the minute with a fidelity and complexity never imagined by any of the inhabitants of our favourite published fictions. It's the unnamed, unpublished fictions that are the real majesties of the human creative spirit—only we're so velocitized to their presence that we forget how incredible they are.

It's in the connections that you and I forge between ourselves and the objects around us (whether animate or inanimate) that we develop the story of the world. The relationships that we draw up and then (magnificently) prove, whether between human or animal or vegetable or mineral or—most elusive of all—ideological, are fictions we craft to lend credibility to a universe that is plainly beyond the scope of any of our powers to comprehend. And because we are each of us so adept at worldbuilding, at composing a believable circumstance in which the stories of our lives might unravel themselves, we never blink at the suspension of disbelief that goes on when we do simple things like pay for gum in a supermarket line. Or when we attend a class on macroeconomics that we're merely auditing. Or when we watch a Youtube parody of Peter Jackson's film adaptation of JRR Tolkien's published story version of a storyworld that he created long before he refined it for the page. We're so talented that we would never dream of couching our interaction with the world in terms of suspended disbelief. It's only when our worldbuilding conflicts with the builded worlds of those around us that we encounter dissonance.11And from there come the frustrations and fights and divorces and murders and wars which comprise the bulk of both our nightly news and our entertainment.

So yeah, worldbuilding is serious, big-deal stuff. It's also so completely normal and average that we almost safely ignore it completely and only use the term to describe its lesser cousins, fantasy worldbuilding and science-fiction worldbuilding. Cameron Stewart hints at this not-quite-subterranean sense of world creation in Sin Titulo. That he does so through thoroughly science-fictional terms does little to dilute his comic's exploration of the worlds we craft for ourselves. The book doubles as both a mind-bending, reality-melting thriller and a discussion of what it means to build worlds (in any of its senses).

I probably might not have come to think of Stewart's story in this way had I not sat and puzzled over the purpose of the book's title, Without Title, sin titulo. What kind of works are the ones that remain untitled? Either the pretentious ones or the ones that seek most baldly to engage the viewer, reader, listener, or audience. Presuming that Stewart's work is not pretentious (a preference and presumption I'm willing to extend simply for how beautifully composed his artwork is), that means that Stewart wants us to think more about his work than what he's laid out most plainly in the map of his panels and in the legend found in his bubbles. He hopes his readers will depart from the trail, explore a little, forge a path through the underbrush of his story. I mean, obviously I'm guessing here. But I think the clues are there.22Plus, I have a double ear infection so all sorts of things make sense that might not otherwise coalesce. I feel like I might actually be magic right now.

As the bulk of Stewart's discussion of worldbuilding occurs in his climactic, expository finale, I'll demur from speaking too specifically. The author does discuss the difference between worldbuilding and true worldbuilding, founding his argument on a sort of embellishment of the Platonic forms. He posits that the true artist's concern is with creating reality rather than imitating it. In a way, we could read this as a dismissal of Tolkien-esque worldbuilding and a promotion of the kind of reality-forging that takes place in you and I in every moment. He doesn't stop there and I'm not sure he or his characters would be entirely comfortable with this reading, but that's the story within his story that affected me—the story of several characters trying to build realities in which they won't be sickened by themselves and their weaknesses. A story that somewhat exists as pedagogy, a nudge to the reader toward an existence in which the stories we create for our lives eliminate our weakest selves and one in which our histories are not our fault.

It's a neat trick Stewart devises and it's well told. I'm not sure how ultimately convincing it is, but I'm also not sure it's intended to be that kind of a tract. Rather, Stewart leaves breadcrumbs to discussions that will be had outside his work—discussions in critical forums, bookclubs, classrooms, and in the space that exists between spouses and their conversation while driving to dinner on a Sunday evening. Sin Titulo, actually, is almost the perfect bookclub novel. Under two hundred pages, sitting squarely in the John-Warner-coined genre of the white, male fuck-up novel, and fraught and teeming with those kinds of interpretive hooks that lead to high anxiety frenzy and argument in the better bookclubs that dot the national landscape. It's a book about social anxiety, severed relationships, love and its absence, second chances, and the means to constructing a life that will be, at last, worthwhile and whole. Stewart's built something rather beautiful (for all its ugly bits) and even if I'm reading it entirely wrongly, I'm happy to be a part of the mythos that it develops.

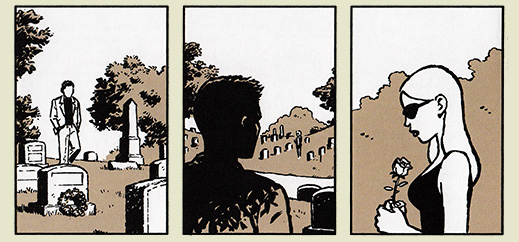

I'd never read a book entirely composed by Cameron Stewart, and for all I know this may have been his first solo comics work. Whatever the case, Sin Titulo is a lovely production. The pages, while long and squat, hold bold and thick-lined panels filled with dynamic art—made moreso by the choice to use a taste of burlap for the book's only shader, earthy and monochromatic. The paneling sits in a uniform four-by-two grid (though here I've only reproduced rows of three for legibility reasons, and I don't wish to spoil any story surprises). Sin Titulo's cover gives up one of its greatest images, the recurrent lone tree, but at a certain point when the motif breaks from format, I found myself caught unguarded by its forceful presence. Again, lovely work.

Different readers will appreciate Stewart's narrative more or less than each other, and probably across a great range. Its twisting nature is of the kind that especially appeals to college-aged men who delight in those mind-blowing what-is-real-anyway stories like The Matrix, Donnie Darko, The Thirteenth Floor, and Dark City.33All movies that I have enjoyed, fyi. Readers less enamoured with that particular trope may find themselves struggling over whether the narrative earns its conclusion. It's one of those stories that has a thousand dangling threads twenty pages before its final page and then neatly ties them up with a bunch of people standing around talking exposition. That works within the tradition Stewart's engaging here, but non-fans could be frustrated by what they might (I think unfairly) categorize as a Scooby-Doo Ending.

And at any rate, all this just builds on Sin Titulo's value as a great bookclub choice. Bookclubbers will have tons of fun drinking too much mulled wine and arguing about the book's titlelessness and which character is the worldbreaker44I mean, if they've read Spera vol 3 maybe? and which girl they ship for poor Alex and whether he deserves anyone. Someone get Oprah on the line.55I don't know. Does she even still do a bookclub? I haven't seen those gold seals in a while, but since the Borders closed up in my town, I haven't really gotten out to brick-and-mortar (do they still use brick and mortar?) bookstores in ages.

Good Ok Bad features reviews of comics, graphic novels, manga, et cetera using a rare and auspicious three-star rating system. Point systems are notoriously fiddly, so here it's been pared down to three simple possibilities:

3 Stars = Good

2 Stars = Ok

1 Star = Bad

I am Seth T. Hahne and these are my reviews.

Browse Reviews By

Other Features

- Best Books of the Year:

- Top 50 of 2024

- Top 50 of 2023

- Top 100 of 2020-22

- Top 75 of 2019

- Top 50 of 2018

- Top 75 of 2017

- Top 75 of 2016

- Top 75 of 2015

- Top 75 of 2014

- Top 35 of 2013

- Top 25 of 2012

- Top 10 of 2011

- Popular Sections:

- All-Time Top 500

- All the Boardgames I've Played

- All the Anime Series I've Seen

- All the Animated Films I've Seen

- Top 75 by Female Creators

- Kids Recommendations

- What I Read: A Reading Log

- Other Features:

- Bookclub Study Guides