The Sculptor

I don't like to think about death. I mean, I do it all the time. You can't read very much literature or encounter many movies without being confronted almost constantly with the mortality of the species. But almost exclusively, in that transmission from author to story and then to me the reader, there is a level of abstraction to the concept that renders death palatable—or at least digestible. That's the curiosity.

Death is such a terrible, final horrorshow of mystery that nearly any expression of it in art or narrative deadens it. Death becomes, suddenly, a toy—a plaything for abstracted meanderings—a way of fooling ourselves into imagining we might be able to get a handle on our own return to mulch and to dust. But there's always going to be something inevitably fake about the stories we consume. Sometimes we'll think, Oh! What a clever way to have killed that character! or Oh! What pathos! But because we're aware that these characters are fictions, there's always going to be some part of us reserved, held back. It won't be real. Not like real death really is.

A couple years back, I had a health scare that thankfully was both brief and really nothing more than a scare, a little jack-in-the-box that popped out to say Boo! and remind me that life wasn't safe. Throughout the waiting period—waiting to hear whether I was to be merely startled or straight-up terrified—I was largely philosophical about the possibility that I might die, that this might be the end of me as Me. Stories had taught me myriad paths to distancing myself from reality. Coping mechanisms, not in name but in practice. I was able to consider the impact on those around me and to plan for inevitability, all with minimal emotional investment. I could prioritize projects, knowing which could be completed in time, which weren't worth pursuing, and which could leave my best plausible legacy. I was obviously unhappy with the prospect that I might depart this age prematurely, but Hey, that's life, right?

But then I struck upon the idea that I should record two short films, one for each of my young children offering them each advice for life, telling them a little bit about myself, letting them see a warm fifteen minutes with the father they would never have the opportunity to really know or remember. Rehearsing what one of these thoughtful expressions might sound like, I broke. I was in that moment granted a certain clarity that had previously been elided. The full weight (or what I imagine to be a full weight) of my mortal state bore down on me and I saw everything that I would be leaving and everything that would be left by me. I couldn't breathe. I couldn't speak. I cannot express in any terms what that moment meant to me but to say: in that instant, I became focused in a way that would be impossible for me otherwise. Of course, I no longer possess the crispness of that epiphany, but I do remember that it happened. Scott McCloud's The Sculptor doesn't do anything to make death real to readers (death works in the story as a gimmick, a funny character, and a plot device), but what it does sell particularly well, I think, is that moment of clarity.

Protagonist David is a struggling New York sculptor. He is the last in his lineage, the remaining son in a family built of people who die young at the hands of cruel fates. And having made a recent bargain with an incarnate reaper of souls, he will die young too. As he approaches his expiration date, he bounces back and forth between panic and acceptance. In either case, his interaction with death is mediated by the fact that he still doesn't know what he thinks about life—and if one doesn't know what they think of life, then how can they know what to think of the collapse of life?

David's bargain with death grants him a limited-time supply of magic sculpting powers, and as the time limit begins to wind down, he throws himself into a final work. One that won't be discovered until after his death. It's the entirety of his experiences pressed into a single, intricate work. It's everything he knows and believes. It is his absolute expression of his art. And then, suddenly, it isn't.

An event occurs just before David's finale that brings him the clarity and focus that is kind of the essential motivator in those who are aware of their imminent demise. It doesn't mean his judgment in the midst of that clarity is better or more wise. But he is seeing, rather suddenly and with force, what it is that he thinks of life, what it all means to him. And so he creates a second final piece. A sculpture that says everything he finally hopes to say. And perhaps ironically, none of his substantial audience will be able to decipher his meaning. Even the best, most crisp, and most acute communication eventually collapses and is lost in the static of time and distance. It all dies. Meaning and purpose vanish. Sometimes years later, sometimes instantly.

David is haunted by the possibility that he might not create some thing that will secure his immortality in that very mortal way by which we understand Michelangelo and Picasso and Shakespeare to have been immortalized. He is terrified of being forgotten. At one point, David shares this fear and has his perspective challenged. Rather than fear that we will be forgotten, he is admonished, we should embrace our transience—we should exult in our temporary place. The suggestion is made: own it, own your inevitable mortality, own the fact that you will be forgotten, whether forgotten in a hundred years or in a hundred days. The solution offered: create a secret, a momentary parcel of meaning intended to exist only so long as its single recipient survives and then to be forgotten and lost for all time. Something powerful precisely for the intentionality of its transient nature.

And in the end, David has two posthumously unveiled pieces: the penultimate piece that aimed for immortality and the final piece whose meaning is lost immediately. Each in their way is a celebration of life, but only the last was that crisp concatenation of David's sense of the world. And only in that final piece is the madness and lunacy of death actually confronted.

The Sculptor is a large work, too difficult to summarize in anything so concise as one of my reviews. It's got a lot of moving pieces, a lot of ideas. Instead, here's something a little different from my usual review: a scattered collection of bullet points.

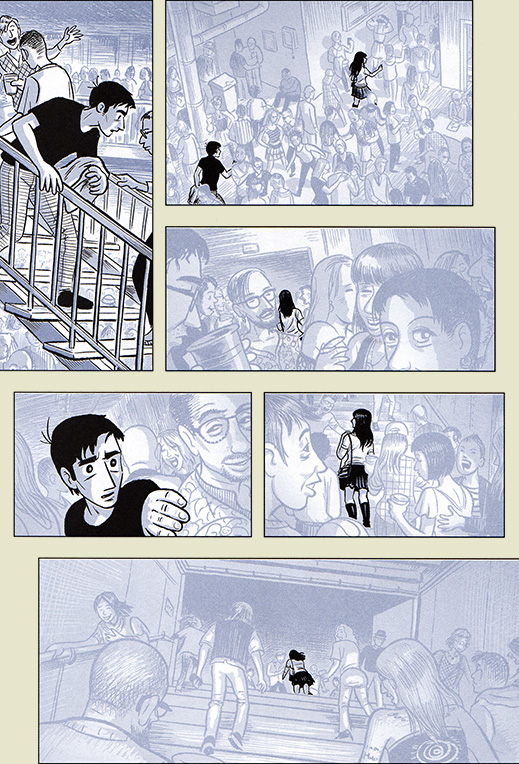

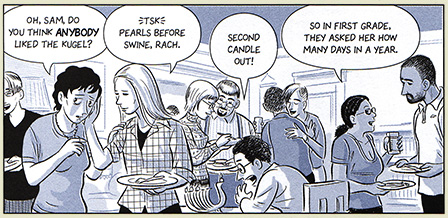

- McCloud does a great job of making his city into a vibrant, lively place. The panels are often filled with people, walking here or there, inhabiting their own stories. Snatches of their dialogue pingpong through David's story, underscoring the fact that despite however he may feel, he is not alone.

- The cast is diverse. Even if David's circle of friends are largely of lighter complexion (probably what one would expect from those in New York privileged enough to live in the city and toast among the toast of the art set), McCloud fills his book with figures of all sorts of shapes, sizes, ethnicities, and cultural profiles. He gives his New York a very cosmopolitan feeling, one that's missing from a lot of comics stories, I think.

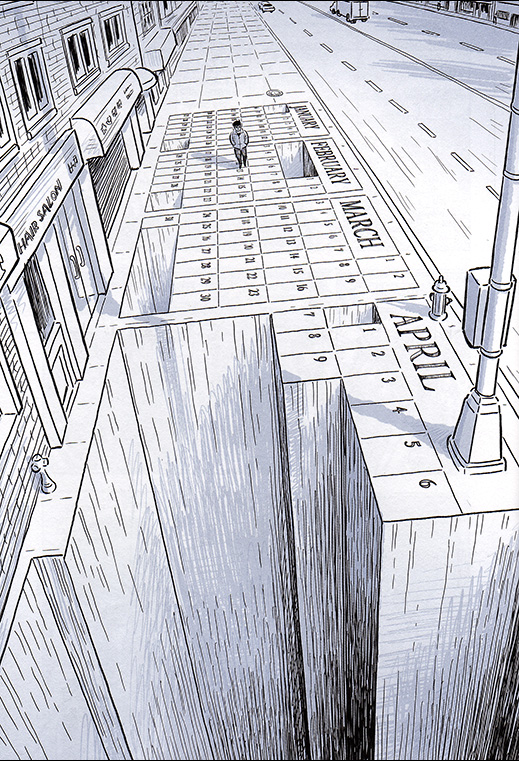

- McCloud's illustration work is a bizarre chimera of intricate and sloppy. His page designs are tops and the storytelling from panel to panel is lovely. His linework is rough and is often just layers of scribbles. Shadows are a mess and some characters' hair is just hilarious. But for all that, there's a certain cohesion to the style—and if he didn't draw with such a speed-conscious style, we likely wouldn't have seen The Sculptor until well into 2025. I'm always kind of aggravated by detecting the obvious presence of digital tools in comics art, but after a few minutes managing my prejudices, I gave in to the story and was largely able to forget my tastes. And then some of McCloud's pages are just so exquisitely designed and such idea-triumphs that he bowls you over. Like this picture in which David is haunted by the diminishing days remaining on the calendar of his life:

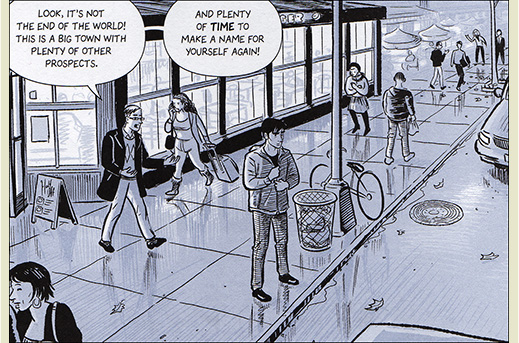

Also pretty cool is the way he uses his varying blues to achieve the look of a sidewalk wet with recent rain though no rain is presently visible:

- I liked this book. The Sculptor is not my favourite book but it is a good book. It has so many many things to think about and it bears up well under repeated reading. I've read it twice now, with two months between readings, and I saw different things each time. And that's something I like in my books. Growth, evolution.

Good Ok Bad features reviews of comics, graphic novels, manga, et cetera using a rare and auspicious three-star rating system. Point systems are notoriously fiddly, so here it's been pared down to three simple possibilities:

3 Stars = Good

2 Stars = Ok

1 Star = Bad

I am Seth T. Hahne and these are my reviews.

Browse Reviews By

Other Features

- Best Books of the Year:

- Top 50 of 2024

- Top 50 of 2023

- Top 100 of 2020-22

- Top 75 of 2019

- Top 50 of 2018

- Top 75 of 2017

- Top 75 of 2016

- Top 75 of 2015

- Top 75 of 2014

- Top 35 of 2013

- Top 25 of 2012

- Top 10 of 2011

- Popular Sections:

- All-Time Top 500

- All the Boardgames I've Played

- All the Anime Series I've Seen

- All the Animated Films I've Seen

- Top 75 by Female Creators

- Kids Recommendations

- What I Read: A Reading Log

- Other Features:

- Bookclub Study Guides