Saturn Apartments

Generally, there are two kinds of science fiction. The most common are stories that use imaginary technologies, alien races, and futuristic promise as a gimmick, a means to wowing audiences with slick bombast in order to distract from narrative deficiencies. The original Star Wars, for all its good points, makes prominent use of this technique. Viewers are confronted with impressive fabrications—TIE fighters, droids, a landspeeder, the Millennium Falcon, the Mos Eisley cantina, and the Death Star—all to the end of camouflaging bad dialogue and weak acting. Certainly we give ourselves over to the film's charms, but Star Wars uses its setting to disguise its weaknesses.

Less common are examples that use science fiction as a means to approach social issues from a perspective divorced from a reality that may be overladen with presuppositions and biases. These stories extrapolate worlds that may someday exist in order to speak to present concerns. Gattaca, A Brave New World, Fahrenheit 451, and 1984 each use their setting for the purpose of something more than simply providing an engaging entertainment.

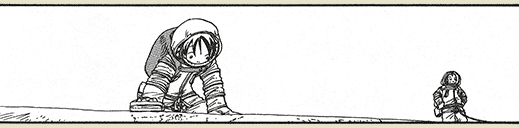

Hisae Iwaoka's Saturn Apartments is somewhat enigmatic then, in that it seems to fit neither of these categories. While the book does include a number of set pieces that provide fantastic viewscapes (notably, some gorgeous illustrations of the earth from outside the book's principal space structure), these have no narrative inadequacies to cover up. And while the book does present a world in which the strict class systems common to some dystopian fiction exert a negative influence on its cast, making social statements seems to be the least of Iwaoka's concerns. (That may change as the story evolves, but as of the first two volumes, she doesn't seem overly interested in addressing social inequity.) Instead, the futurism and social state of Saturn Apartments seems in place wholly to the end of presenting a fully forged world in which Iwaoka's small story can take place.

When I say small story that is only to say that this is not a book devoted to national or interspecies struggles. This is not a series about the end of the world (in a way, that already happened). This is not the story of good vs. evil, the rescue of a princess, or a race to recover a lost treasure before it's lost for all time. It's the story of a boy who's just joined the workforce and is trying to come to grips with who he is in the shadow of his father's death five years earlier.

And in that way, Saturn Apartments may actually be a bigger story than Star Wars or Lord of the Rings. After all, every person is an expansive universe of interests, motives, stories, treacheries, and dreams. And each of these universes is governed by an entirely unique set of forces, every bit as sovereign as gravity and entropy.

In Saturn Apartments, the earth (for reasons as yet untreated) has been abandoned for decades, existing now as a global nature preserve. Whether due war or pollution or a humanitarian attempt at a Babel-like house to scrape the heavens, the reason for the current state of the earth is, seemingly, apart from the interests of the series. All that matters is that the earth has been abandoned and all the remnant humanity dwells on a great ring encircling the earth in low orbit, pretty much smack in the middle of the stratosphere. While never explicitly referred to within the text as the Saturn Apartments, the ring does make the earth resemble Saturn a bit. Or at least maybe Uranus. The ring itself is divided into three strata: upper, middle, and lower sections. The middle section is devoted to public works such as schools, parks, government, and scientific endeavors. Elites live in the upper reaches of the ring while everyone else is shuffled into the lower division.

Saturn Apartments' primary narrative conceit (I mean, beyond the ring itself) is that somebody's got to wash all those windows. Dwellings that sit on the epidermis of the ring have windows that look out into the reaches of space (everyone else has to content themselves with artificial light and skies) and, even in space, a film of dust gradually accumulates. Those with the money to do so hire window washers to help them keep their perspicuity. As washers require space suits, months of training, and hours to pressurize in order to clean windows, it's rare that anyone from the lower levels has the opportunity to clean their windows; ironically, it's these grime-caked windows of the lower levels that face the earth and the spectacular view that such portals could provide.

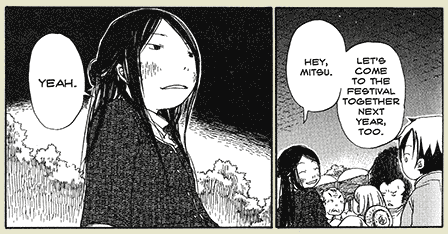

Iwaoka's protagonist is Mitsu, the orphaned son of Aki, a washer who fell to earth in a window-washing accident five years ago. Mitsu has just graduated high school and is accepted into his father's guild, where he encounters all of Aki's old friends and co-workers. Mitsu is both diligent and distracted, the presence of a hard-working father he barely knew weighing heavily on his life and direction. He's a little bit lost, a little bit unformed, and pretty uncertain about his purpose in things. He's eager to find and prove his place within the guild but until he discovers himself for who he is, he'll never be able to confidently chart his own personal destiny.

Saturn Apartments plots Mitsu's course through the interpersonal exchanges he experiences with co-workers and clients and then through the friendships he forms as a result. Mitsu's path evolves from one marked by loneliness toward something a bit more rounded with a breadth of human contact. Much of the fun of the series is watching him negotiate these new relationships while he takes cues from those around him in an attempt to understand how normal people interact. He's a great observer and does his best to conscientiously apply the practical knowledge his observations lend him. By having Mitsu intersect with a variety of lives from the outside literally looking in, Iwaoka leaves herself plenty of room to explore numerous story and relationship paths before wearing out her and Mitsu's welcome.

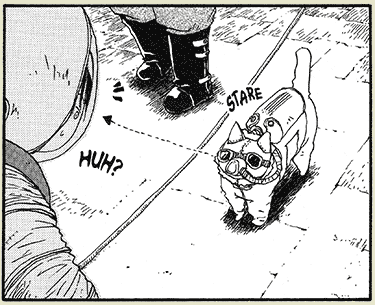

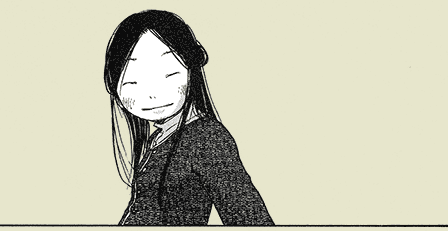

One of the charms of Saturn Apartments is its unique visual sense. Iwaoka employs a style of illustration uncommon in the manga I've yet encountered. Her character compositions sit far from what we may have come to expect from our Japanese comics, neither favouring the bold dynamism common in shōnen nor the ephemeral willowiness often present in shōjo. Iwaoka instead essays what I imagine would have to be some sort of indie manga. Her line is confident in its hesitance, a practiced stutter. In many cases, independent creators have more imagination than they have talent; this is decidedly not the case with Iwaoka's work. She creates big-headed people and her men are often distinguishable from her women by fashion alone—all, I suspect, by design. She also frequently employs visual gags to lighten the mood of what could otherwise be a book too sober by half.

Saturn Apartments is an exciting book to take part in as its release gradually unfolds. Generally, I prefer to take in a series once its publication is complete (therefore eliminating the story-hindering two-to-ten-month wait between volumes), but Saturn Apartments is such a quiet pleasure for me that I'm happy to take it in whatever chunks are available to me.

Good Ok Bad features reviews of comics, graphic novels, manga, et cetera using a rare and auspicious three-star rating system. Point systems are notoriously fiddly, so here it's been pared down to three simple possibilities:

3 Stars = Good

2 Stars = Ok

1 Star = Bad

I am Seth T. Hahne and these are my reviews.

Browse Reviews By

Other Features

- Best Books of the Year:

- Top 50 of 2024

- Top 50 of 2023

- Top 100 of 2020-22

- Top 75 of 2019

- Top 50 of 2018

- Top 75 of 2017

- Top 75 of 2016

- Top 75 of 2015

- Top 75 of 2014

- Top 35 of 2013

- Top 25 of 2012

- Top 10 of 2011

- Popular Sections:

- All-Time Top 500

- All the Boardgames I've Played

- All the Anime Series I've Seen

- All the Animated Films I've Seen

- Top 75 by Female Creators

- Kids Recommendations

- What I Read: A Reading Log

- Other Features:

- Bookclub Study Guides