Sandcastle

Created by: Pierre Oscar Lévy and Frederik Peeters

Published by: PUBLISHER

ISBN: 1906838380 Amazon

Pages: 113

I'm not a fan of poetry. Never have been. There's always been some obstacle between me and my enjoyment of what so many others seem to dig on. That said, there are a couple bits here and there that I've enjoyed. A line, a stanza, an idea. I liked a poem an English professor friend of mine wrote because it mentioned Bubo, the mechanical owl from Clash of the Titans. I liked bits of "To His Coy Mistress" because it was absurd and, so, funny. And I liked bits of Shelley's "Ozymandias." You know, "two vast and trunkless legs of stone" and all that. I heard the poem in seventh grade and the whole idea resonated with me—the fragility of kingdoms, the temporary nature of everything we are and do.

I grew up on the beach. We moved to the coast when I was three. I stayed near the sand until I was thirty-two. In those nearly three decades, I built a lot of castles, sometimes in the traditional sense, packing sand into shapes and then carving out everything that wasn't "castle" from the mass. More often though, I crafted what my dad (our master craftsman to whom we were apprenticed) had termed dib-dab castles.11I've since learned from Wikipedia that these are probably more commonly called drip castles, though a good number call them dribbled castles. These are constructed by taking a fistful of very wet sand (a slurry) and letting it drip in a controlled manner from the hand. The castles are wonderful and organic and amazing when well-produced. Here's a basic tutorial:

And yes, dad, I know that if I held the sand so high above it would demolish the castle below. I drew the large space between to illustrate the 3 steps: 1) the hand holding the slurry, 2) the wet sand dripping down, and 3) the drops of sand solidifying into a castle. Window included, just like I was taught (by example). And of course, the greatest tragedy of each of our creations was their limited duration. Not one single fortress survived the night and the rising tides. No matter the strength, value, or beauty of the castle. Time and tides swept flat every kingdom. By comparison, Ozymandias' kingdom was particularly tenacious, leaving those two stone trunks.

Books about the mortality of the race are not rare. In fact, most stories can in some sense be read as an exploration of our perishable nature, of our inevitable expiration. The fact that we will all die pretty much sooner than we'd prefer motivates (even if only subconsciously) so much of our narrative displays—and of course our real-world actions as well. One of the saving graces of the human experience is that without the intervention of some terrible accident (injury or disease or murder), we all get at least six decades to gradually make sense of the whole tragic mess. Those years and years of intermittent contemplation may bring us to peace or push us toward existential horror, and that's what centuries of literature helps us explore. Sandcastle is no different, and by collapsing those decades and years and months and days and hours of potential meditation into the span of a day or less, authors Frederik Peeters and Pierre Oscar Lévy force the issue rather neatly.

Sandcastle, like most Twilight Zone episodes, is heavily plot driven. The reader's first pass is going to almost inevitably be wholly invested in the question of Holy Crap What Is Happening?! The book is written and drawn with judicious tension. Lévy and Peeters grab hold of one's attention deftly and don't show any concern with offering relief until the book's final curtain draws closed. It's an exhilarating ride and well worth the ticket paid.

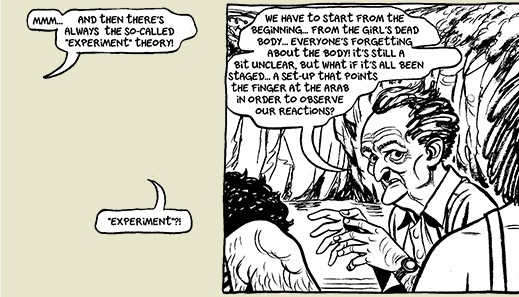

Partway through, however, readers will begin to sense that the plot, the story, the mystery, and whatever climax awaits is probably beside the point. Sandcastle is thoroughly invested in the human dilemma—that bit of story that takes place in between plot points. Lévy and Peeters offer a neat entry into their discussion of the human end, lubricating the conversation by its relevancy and immediacy. The characters are rather typical, but that allows us to investigate the typicality of their conundrum.

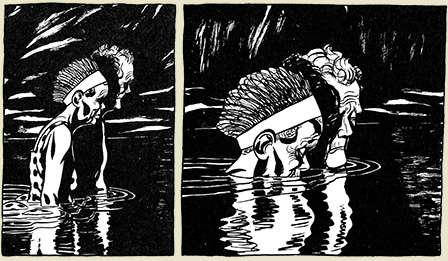

Throughout Sandcastle's paces, it's never quite clear whether the nature of the book's MacGuffin is founded in science fiction or magic—though various clues point toward some sort of fantasy sci-fi. Visitors to a secluded lagoon in (probably) Spain find themselves trapped there by mysterious means. More alarmingly, they rather quickly find themselves aging with alacrity—at something like a rate of one year in fifteen minutes. The elderly begin to expire, the children hit puberty early, and the younger adults try to figure out what to do. The authors use the generic character tropes as a means to more immediately bridge the gap between the reader and the question that hangs over each of our lives: What do we do with the fact of our limited time in this sphere?

He was going to say: without riding a pony

He was going to say: without riding a pony

Even as Sandcastle is itself a grand parable for those with ears to hear, Lévy and Peeters have seen fit to include a couple smaller interior parables for easy lessons and digestion. One is in the nature of the sandcastle itself, titular and obvious, finding itself expressed through several iterations over the course of the tale. Another is a swansong fable about a king who so feared death that he entombed himself to keep the spectre at bay. The careful (or lucky!) reader may discover more breadcrumbs and trails that the authors have laid out, all to the end of better engaging their subject.

Biology *is* cool!

Biology *is* cool!

The dialogue is simple and maybe sometimes a little awkward. This may be an artifact of translation or it may issue from vacationing foreigners all trying to speak in a common tongue. In the growing children's case, it may show that while their minds mature and they acquire some of the intelligence natural to their age,22Such as the five-year-old girl who, after having sex well after puberty (a.k.a. lunchtime), discovers bleeding and explains it to her partner as either the natural result of their intercourse or perhaps her period. Not the usual information for five-year-old to have at a ready hand. there's still a bit of social awkwardness attached to the absence of experience. The personalities, too, seem immune to aging. The petulant teenage girl still lives to frustrate her parents even at the age of thirty. The five-year-old girl still loves her parents with wide-eyed affection, even well into her newfound adulthood. And the three-year-old boy is as detached from the immediacy of his situation as an adult as he was as a child. And all of the children will sit bound and tight for a good story, even in the midst of imminent death.

Everybody loves a story!

Everybody loves a story!

Peeters, whose art is full and lively, describes the book as a parable. And it is. Sandcastle is one more opportunity to prompt our thoughts toward consideration of our mortality and if there can be any meaning in it. These parables surround us, whether in Shelley in junior high or in the kingdoms we build as children in the sand, but we are—as a species or as a culture—so prone to forgetfulness and distraction that reminders, even obvious ones, can be welcome. Even for those who believe they know about life and death and afterlife and afterdeath, the privilege to reconsider the limits we're born with is a gift that should not be squandered or abdicated. We are already, as a people, so very arrogant. Why not take the opportunity to take on the humiliation of mystery?

Good Ok Bad features reviews of comics, graphic novels, manga, et cetera using a rare and auspicious three-star rating system. Point systems are notoriously fiddly, so here it's been pared down to three simple possibilities:

3 Stars = Good

2 Stars = Ok

1 Star = Bad

I am Seth T. Hahne and these are my reviews.

Browse Reviews By

Other Features

- Best Books of the Year:

- Top 50 of 2024

- Top 50 of 2023

- Top 100 of 2020-22

- Top 75 of 2019

- Top 50 of 2018

- Top 75 of 2017

- Top 75 of 2016

- Top 75 of 2015

- Top 75 of 2014

- Top 35 of 2013

- Top 25 of 2012

- Top 10 of 2011

- Popular Sections:

- All-Time Top 500

- All the Boardgames I've Played

- All the Anime Series I've Seen

- All the Animated Films I've Seen

- Top 75 by Female Creators

- Kids Recommendations

- What I Read: A Reading Log

- Other Features:

- Bookclub Study Guides