Polina

I had sat down to write a review of Bastien Vivès' Taste of Chlorine, a beautiful book that dances around the skirts of a public pool, exploring a relationship that develops amongst swimmers in that place. I had already finished my opener, a minor discussion of the wonder and mystery of language—of how we make ourselves known in the murk of the unknown. And then another book arrived on my doorstep, a package from Amazon UK. I hadn't been expecting it so soon. It was publisher Jonathan Cape's latest release from the author of the book I was at that moment reviewing. The book was Bastien Vivès' Polina, and all hope of me finishing my Taste of Chlorine review that night was wholly evaporated.

In September 2013, I returned from the Small Press Expo galvanized. In the midst of those gathered hundreds of artists and writers who had actually created wonderful and intricate works of comics art and story, I found myself compelled by the need to create one myself. I knew I didn't have the time or confidence to do anything of real length so I thought I might try putting out a couple mini-comics. And who knows? Maybe that'll help me better appreciate the form for my reviews? That's what I was telling myself. But really, I wanted to build something substantial. Something, perhaps, great. In the back of my head and heart, I wanted to create a full-length graphic novel about classical dancers. Ballerinas, if you will. I have four astounding friends who are professional ballet dancers, scattered around the North American continent. Seeing them work so hard and struggle and succeed and stumble and rise is inspiring. I knew there was a fascinating story there. (I even doodled up some little sample art.)

And then, in the middle of September, I saw on Zainab Akhtar's site a news bulletin alerting readers to the English translation of Bastien Vivès' Polina, a book concerned with the life of a Russian ballet dancer. Akhtar included some few page samples. I was floored. They were beautiful. I didn't even have time to be upset that someone had beaten me to my half-formed zygote of a dream. I was too excited. I was only angry to find that the book wouldn't be released in English until January (and in America, who knows?).11And yes, I am that entitled sort of reader who demands that every book be continuously and presently available on the off chance that I will want it that week. It kills me to have to wait for wonderful things. I have no patience.

My excitement, as should be plain by the fact that I'm foregoing my Taste of Chlorine review, was well-justified. I had expected something good. I had even expected something beautiful. I had not, however, expected a work as accomplished and perfect as Polina.

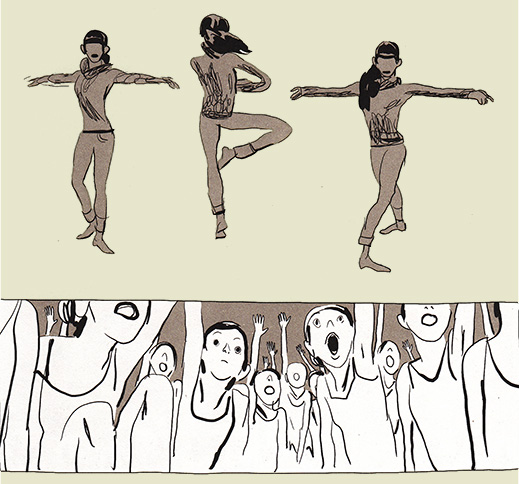

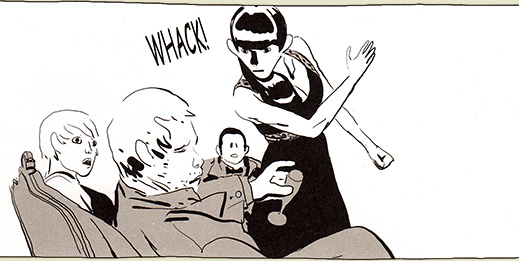

The first thing a reader will notice is Vivès' illustrations. His figures are compositions of gestures, scaffolded together by the merest hint of connection. Thin lines and black blobs of ink dance across the canvas of each panel, outlining a space that I fear to paint too breathlessly. I'm very conscious of myself here and exerting considerable force on my need to wax eloquent in praise of what exactly Vivès does. His artwork is spare and organic. What appears on the page is often either ephemeral or fantastically dense. His layouts and choice of subject feel in every instance to be The Right Choice. He tells his story visually with such great aptitude that I cannot imagine this story being better served by any other illustrator.

Sorry, there I go breathless again. I can't tell the difference between objective praise and subjective adulation anymore, so please forgive me and read that into my review.

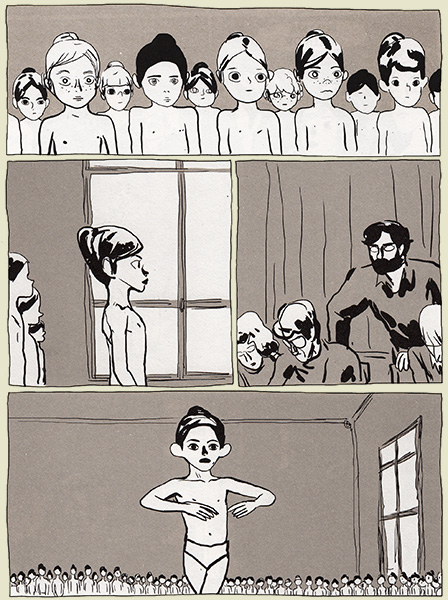

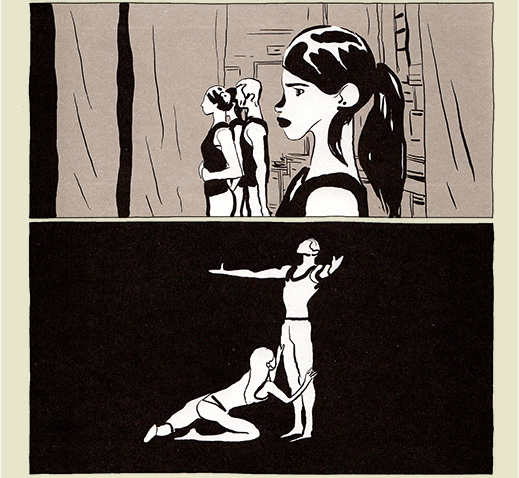

In a book about dancers, perhaps the one great question is how well Vivès captures the flow and sublimity of the human form and the precise gracefulness required of it in the dance. I can't say whether or not his work comes easily, but because Vivès conveys his subjects' lithe and supple movement so naturally, his illustrations appear effortless. It helps that his style here is closer to impressionistic than realist; that allows him to focus on exhibiting his intent rather than working counter to purpose by getting lost in details. And while Vivès will occasionally fill his backgrounds with intricated set designs, he still more often provides either no background at all or only the merest fragile skeleton of a setting for his characters. This permits his dancers to float in negative space, buoyed in an elegant frame of nothingness. They are the subjects and they communicate with their bodies even apart from the context of the spaces they would actually be inhabiting. It's a powerful technique and does much to lend weight to the presence of his actors.

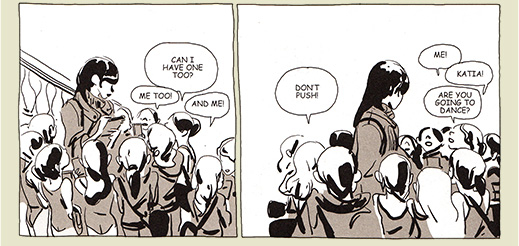

Vivès' story is lively and important—in the sense that any time we follow a child through to adulthood, the movements that carry her along must be of great moment. And nearly every page of Polina works to this end. Every moment is of moment. Every moment is a work of art.

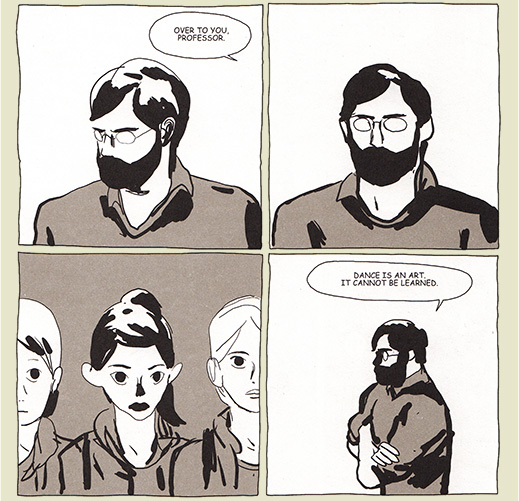

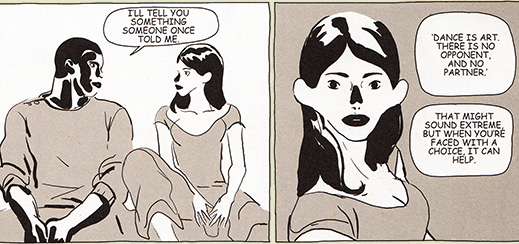

At about the halfway point a friend relates a maxim to Polina, a little something that carries him through: "Dance is art. There is no opponent and no partner." Polina, as Vivès presents her, is herself art. She is in every instance an artistic effort, a creative impulse intended to convey a creative impulse. Her carriage is practiced, her posture intentional. Bojinsky, the imposing figure who instructs Polina from her childhood, reminds that "The audience must see nothing except the emotion you are conveying. If you don't show them grace and lightness, they will only see effort and strain." Of her own intention or merely by Vivès fateful hand, Polina's every appearance is an exploration of her teacher's admonition. Vivès is intent on pushing tremendous readability into every panel. We know Polina's thoughts by her look, by her face, by the way her body hangs in the space she occupies. We know her relationship to those around her by Vivès' use of positioning and body language.

In Polina's climax, Vivès redirects wholly our perception of things through a few panels in which he temporarily alters a character's depiction—and in so doing, reveals the facade of so much of what we've already seen. It was a bravura moment. Vivès, without fanfare, turns so much of everything on its head and through a simple artistic decision gives the reader a lovely kind of insight into Polina and how her world has been composed. That single juncture of art and story elevated a very strong work to the level of greatness.22It's still very early in 2014, but I'm greatly looking forward to any book this year that is more magnificent or special than Polina. Because that book will be amazing.

Concerning realism, I feel as though Polina is nearly entirely believable. I haven't yet been able to consult my friends to see how much comports to their own experiences, but from what I do know, Vivès keeps our feet firmly planted in the world of dance as it is or may be. There was only a single moment in the book's final act that felt perhaps a little too contrived, a little too convenient. All the same, I didn't mind the strange twist of fate described because I found the rest of Vivès' story so winning, his heroine so fascinating. I was happy for the opportunity to see her involved in a new circumstance, no matter how surprising, simply for the fact that it would give one more window into her soul. Or at least into the art of her existence on the page, specially prepared for the audience Vivès delivers to her.33i.e. you and I and every other reader.

Polina is a book about perception and appearance. The world as it is and the world as we see it and the world as we present it. Polina is about beauty and distress. Polina investigates, by charting a small dancer's path to womanhood, the way the choices we make inform not only our circumstances but the manner in which we see those circumstances. It's rare to find a tightly woven narrative that simultaneously gives its story the chance to breathe, but Polina does that. Nothing, not even the emptiness, feels as excess. All of it is present for its purpose, but Polina introduces us to the idea that being governed by a fate and destiny (as all stories are) doesn't have to feel constrictive.

Good Ok Bad features reviews of comics, graphic novels, manga, et cetera using a rare and auspicious three-star rating system. Point systems are notoriously fiddly, so here it's been pared down to three simple possibilities:

3 Stars = Good

2 Stars = Ok

1 Star = Bad

I am Seth T. Hahne and these are my reviews.

Browse Reviews By

Other Features

- Best Books of the Year:

- Top 50 of 2024

- Top 50 of 2023

- Top 100 of 2020-22

- Top 75 of 2019

- Top 50 of 2018

- Top 75 of 2017

- Top 75 of 2016

- Top 75 of 2015

- Top 75 of 2014

- Top 35 of 2013

- Top 25 of 2012

- Top 10 of 2011

- Popular Sections:

- All-Time Top 500

- All the Boardgames I've Played

- All the Anime Series I've Seen

- All the Animated Films I've Seen

- Top 75 by Female Creators

- Kids Recommendations

- What I Read: A Reading Log

- Other Features:

- Bookclub Study Guides