Ōoku: The Inner Chambers

It all began in seventh grade, as I perused my Nintendo newsletter and discovered that in Japan they had an NES called the Famicon and that the Japanese were able to enjoy new releases sometimes years before we were able to in America. Then, in tenth grade, I discovered Marvel's publication of Katsuhiro Otomo's Akira. And then Akira, the cinematic adaptation. And then I saw pretty much every film Akira Kurosawa ever made. Then I read Shogun. Then I saw Princess Mononoke in theaters. Then everything else Miyazaki had done. Then Usagi Yojimbo. Then there was Haruki Murakami. Then Takaski Murakami and Superflat. Then the manga boom. Really, I've held a fascination with Japan, its culture, and its history pretty much since I first discovered that it had a culture and history that could hold my interest*—and so, the last two-and-a-half decades have left me perfectly primed for Ōoku: The Inner Chambers.

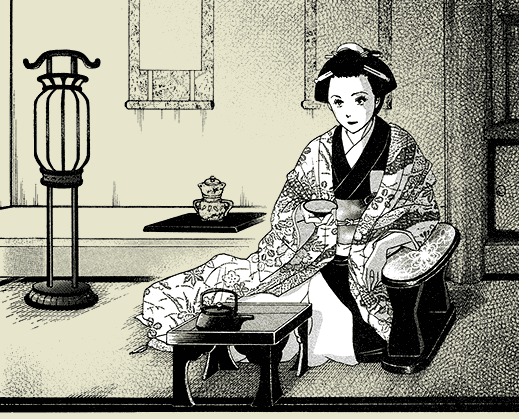

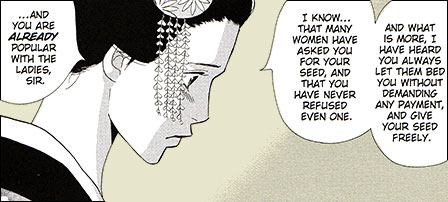

Ōoku is a work of alt-history. It posits a Japan that never happened** and traverses eighty years of would-bes. Taking a page from Y: The Last Man, author Fumi Yoshinaga oppresses 17th-century Japan with a plague, called the redface pox, that decimates the male population of the nation (other countries seem unafflicted). By the time the disease has worked its course, there is only one man for every five women. The national character evolves quickly and drastically under these new terms and the roles of men and women within the society undergo sharp shifts in vocational direction. Women become the primary workforce, tending to all mercantile matters, all fieldwork, and all burdens of government—while men, now prized primarily for their reproductive function, are often sequestered and kept from any exertion that might tax their delicate constitutions. Many men are prostituted by their families to women who don't need the sexual release so much as they simply desire offspring. The Yoshiwara pleasure district quickly empties of women and falls into disuse until it comes to play house to men dedicated to the role of stallion. For their part, women take on the role of lords of households and rulers of domains—even claiming the Shogunate as a female role. And it is with this last that Ōoku is concerned.

Ingeniously, the first volume of the series introduces the situation eighty years after the plague hit, exploring this strange world through the eyes of Mizuno, a young man who enters into the service of the Shogun's inner chamber (what is known as the Ōoku). Alongside Mizuno, the reader learns of the situation of men within what I presume to be the most secretive palace in all Japan—though, to be fair, we have yet to see the Emperor or his/her own inner sanctum. The entire staff of the palace is men. The Shogun keeps for herself a stable of well over a hundred men, none of whom may ever leave the palace grounds—service in the Ōoku is a lifelong duty. With Mizuno, the reader comes to understand the duties, hierarchy, and politics of the place. Nearly upon his entrance into service, the sixth Shogun dies and is succeeded by her young daughter—who also dies soon after, still a child. The succession then passes to Yoshimune, the eighth Tokugawa Shogun, and it is with her entrance that the focus of the book shifts and begins developing a host of protagonists and points of view.

Yoshimune expresses a curiosity for the history of Japan and wonders if there wasn't a time when men were in greater abundance. Using a particular story device, volume two of the series returns to the time nearly a century earlier when the plague first arrived in Japan. Author Yoshinaga then records events from that point onward up until the advent of the eighth Tokugawa Shogun.

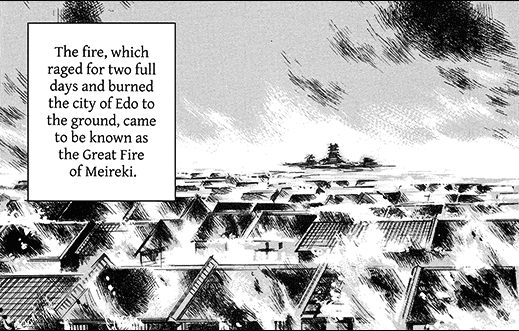

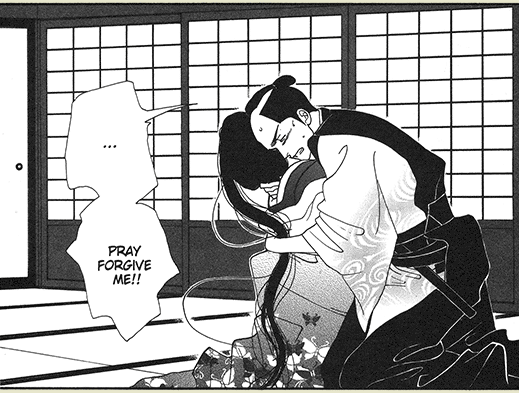

It's a fascinating journey, one full of romance and politics. Yoshinaga is careful to describe in plausible manner just how the power of the Shogun might shift from Iemitsu Tokugawa to his daughter without upsetting the rest of Japan. Part of the genius of the series is that it is entirely history—with narrative embellishments, of course. All the female Shoguns carry the names of the Shoguns as we know them historically. The Shogun following the Iemitsu reign is Ietsuna. And after her, Tsunayoshi. And then Ienobu and Ietsugu and Yoshimune, just like in our world's history. Even the events depicted mirror events recorded as we would know them: the expulsion of the Christians; the plan to burn Edo to the ground; the circumstances surrounding the Forty-Seven Ronin; and probably coming in next year's seventh volume, the Ejima-Ikushima affair.

My only prior experience of Yoshinaga's work was her trifling comedic book of restaurant "reviews," Not Love But Delicious Foods Make Me So Happy. The work here is altogether more substantial and her reinterpretation of history is careful and engaging. Every time I saw her shift her lens to focus on a new set of characters as she travels across the generations, I worried that I wouldn't find the new cast as compelling as the old. Happily those fears proved to be unfounded, as Yoshinaga shows an elegant command of her characters, investing in each of them a host of believable motivations, powers, and infirmities. Japanese history, as recast in Ōoku is excellent drama and I'm thirsty to discover what will happen next and how Yoshinaga plans to wrap the series several years from now.***

Notes

* Tautological, no?

** Some slightly spoilery speculation here (mouse over to view):

I do wonder if Yoshinaga might be here recording not alt-history but presenting a real history—one that is only other than what we have previously known to be the case because it was lost to us. As she is careful to retain all these key incidents, keeps foreign powers from recognizing that the Shogun is female, and retains the male names of Japan's historical rulers (as well as their female consorts), I wonder if she might not—by series' end—return Japan to status quo, with men in roughly equal number to women and have the men return to the seat of power. In such a case, the history of women's tenure in rulership might be understandably lost to the passage of time. It would be an interesting way to take the story and there are some seeds laid to this affect in volume 1, but now that I've thought of it, I'm hoping she'll come up with something even more daring and inventive.

*** Volume 7 should be out sometime in 2012 and the series is projected to be 10 volumes long, with a year between publication of each.

Good Ok Bad features reviews of comics, graphic novels, manga, et cetera using a rare and auspicious three-star rating system. Point systems are notoriously fiddly, so here it's been pared down to three simple possibilities:

3 Stars = Good

2 Stars = Ok

1 Star = Bad

I am Seth T. Hahne and these are my reviews.

Browse Reviews By

Other Features

- Best Books of the Year:

- Top 50 of 2024

- Top 50 of 2023

- Top 100 of 2020-22

- Top 75 of 2019

- Top 50 of 2018

- Top 75 of 2017

- Top 75 of 2016

- Top 75 of 2015

- Top 75 of 2014

- Top 35 of 2013

- Top 25 of 2012

- Top 10 of 2011

- Popular Sections:

- All-Time Top 500

- All the Boardgames I've Played

- All the Anime Series I've Seen

- All the Animated Films I've Seen

- Top 75 by Female Creators

- Kids Recommendations

- What I Read: A Reading Log

- Other Features:

- Bookclub Study Guides