Negima: Magister Negi Magi

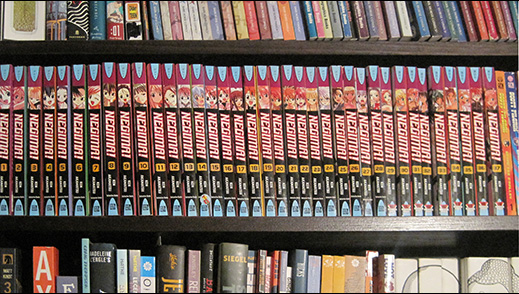

These take up a lot of space

These take up a lot of space

There are very few books I read any more that I'm partially embarrassed by. For the most part I've either abandoned the stuff that shames me or grown confident enough in my enjoyment that I can feel no guilt for reading something others might not understand. And yet, there remains that small number of works that I demur to recommend—or even admit I read.11Let alone admit to owning all 38 ten-dollar volumes of the thing. Negima: Magister Negi Magi is one of those. It's highly embarrassing to me, but I can't stop. Because for all the ways it's really bad, there are as many ways in which it's really good.

Magic, yo!

Magic, yo!

I came to Negima through another guilty pleasure. In 2001 or 2002, I decided I needed to check out all these books that were importing from Japan in the freshly minted manga wave. I had read Akira way back when Marvel was releasing it through Epic and scattered issues of Viz's Area 88 and First Comics' Lone Wolf and Cub, but that was all more than a decade earlier. Coming to manga at that time just after the turn of the millennium was, for me, daunting. There were a lot of titles available and a lot more coming out every month. And despite the internet, it was still pretty difficult to find legitimate critical sources from which to find recommendations. After combing through forums and blogs (2002 was pretty much the zenith of the blogging phenomenon22Or maybe it was 2003.), I saw the title Love Hina crop up often enough that I began to recognize it when walking through Walden Books or Suncoast Video (remember those!). I figured what the heck and picked up Love Hina volume 1 as my first foray into modern manga imports.

The book was bizarre, rather offensive, and kind of intriguing. I was immediately confronted with blatant pandering to a decidedly lascivious male gaze, sexism, and probably even misogyny. My memory of the series is a bit spotty, but I do recall not being comfortable with the book. Still, in the interest of not prejudging cultural expression foreign to my own, I wanted to give Love Hina a fair shake. I picked up the second book, confident that reading two volumes would fulfill Due Diligence and then I could abandon the series. Only, I grew attached to the characters. For all their fulfillment of sexist tropes and promotion of female objectification, these were characters whose plot I became invested in. So I begrudgingly finished off the series.

The conflict within me was real, but I've always been fairly good at sifting wheat from chaff. Being a thinking person whose ideological foundations are constantly evolving with the acquisition of new information, it's rare to encounter a work from any author that doesn't contradict some aspect of my paradigm-shifting belief system. I became, then, accustomed early on to reading books and encountering art that said things oppositional to what I believed. Sometimes those things would be deeply confrontational with the way I perceived the world. So I learned not to be entirely put off by such encounters but to instead compartmentalize for evaluation after reading. It's been a helpful system for me and allows a level of critical involvement impossible were I to simply react in the midst of a text. So that's how I read Love Hina. And that's how I read Ken Akamatsu's following work, Negima.

*hugs*

*hugs*

Not long after I finished with Love Hina, I discovered that Akamatsu would be releasing a new series, featuring a ten-year-old British wizard teaching a class in Japan. I figured I'd give it a shot and hoped that the author had gotten the fan service out of his system.33I'm still rather unaware how endemic this is in the shounen comics industry. I don't know if the inclusion of upskirt shots and bathing scenes is primarily at the whim of the creator or if these things are mandated by editorial—which I understand has a strong role in production. He, as it turned out, had not. And in several substantial ways, Negima is a much more objectionable work than Love Hina is. But it also paints a much more compelling portrait of the women it horribly objectifies.

Negi Springfield is ten years old (almost) and has just graduated from his school of wizardcraft and witchery and the sorting hat has decided that he will be employed at an all-girls junior high in Japan. The girls junior high at Mahora Academy is part of a much larger academic complex, with attached elementary and high schools and university. Its headmaster and several teachers are wizards, so Negi's not completely on his own. Because Negi's only ten and not quite capable of caring for himself (because he's ten), the headmaster installs the boy in the room of Asuna and Konoe (the headmaster's granddaughter). Hijinks, of course, ensue.

Hijinks!

Hijinks!

Not only are there plenty of opportunities for naive and innocent Negi to accidentally stumble into his students topless, bottomless, and any other assortment of awkward pseudo-sexual situations,44Negi, throughout, is generally treated as a sexual neuter, save for when the plot demands that he be the focus of one of his student's amorous attentions. This turns his accidental disrobements, his students' accidental disrobements, and various accidental contacts with sexual anatomy into something odd: innocent for him and (usually) for his students while actively implicating the reader. but the author forces the point regularly. In the beginning, while the series flounders for a few volumes, Negi is given a flaw by which if he is criticized too sharply, he'll sneeze. And if he sneezes, he'll disintegrate the clothing of anyone around him. (Note: he teaches at a girls' school.) Beyond this, several of his students develop feelings for him even though—as Asuna continuously reminds everyone—he's only ten and this makes the whoops-I'm-naked scenes still more awkward.

Scenes like this are not uncommon, like, at all.

Scenes like this are not uncommon, like, at all.

Like Love Hina, the nudity in Negima is coy and silly. The girls are unashamedly drawn fully nude but are nippleless. Either strands of hair or amazing tricks of light work to obscure their nipples so that we never need worry about seeing too much (as if nude fifteen year-olds weren't already too much). Groins are always hidden by legs or other props. The whole thing reminds me of that Mormon bubble-porn meme that was circling the drain a few years back. In the end, I'm not at all sure what to make of this stuff. The girls are drawn like twenty-three-year-olds but their ages put them well below the age of consent, thrusting them into the spotlight of awkward fantasies for I'm sure any number of the title's readership. (Maybe it's all some subtle commentary on the arbitrary nature of social rules like ages of consent vs evolutionary instinct.55Though that's really giving Akamatsu the benefit of the doubt. Or maybe it doesn't matter since the target demographic is fifteen years old anyway? Actually, I don't know who the target age for the book really is.) At any rate, Negi's students are regularly objectified in blatantly sexual manner and not (usually) in service to the plot. It's stale and old and often misogynistic. And I'm sure it does nothing to foster an environment of care and comfort for girls in Japan—or from the guys who read the book over here.

So why bother, right?

That this is an actual outfit worn by a fifteen-year-old girl is pretty much indefensible.

That this is an actual outfit worn by a fifteen-year-old girl is pretty much indefensible.

The strange fact of the matter is that for all that (and actually in opposition to all that), these books—like Love Hina before them—are curiously enjoyable. The real joy of Negima lies beyond its building of anticipation and pacing out of scheduled reveals. Those are all good and fine and keep things moving in the narrative department, but the greatest abundance of Negima's strengths is in its character building. The book begins with Negi Springfield and his class of thirty-one girls, and while some of them only get passing personalities, it's pretty impressive how many of them (an easy majority) Akamatsu explores in better-than-average detail. Through revealing these girls' characters, Akamatsu engages the reader's empathy for their circumstances, bringing greater tension and involvement in their struggles and trials. More than that, by turning these girls into full-orbed characters, Akamatsu actually begins subverting his sexual objectification of them.

There's a delicious66Delicious here is an extremely awkward description of the collision between honest character development and under-age cheesecake, but I think it's fitting for a manga series that is itself awkward. clash between contradictory purposes that actually mirrors how many inhabitants of our paternalistic world are happy to behave. The book posits that these young women are foremost people with strengths and dreams and goals that exist wholly apart from their genetic sexual disposition. They are individuated apart from their relationship to the series' male lead (this is solidified in the series epilogue in volume 38). And yet, for all that—for all their character strength both tied to and independent from their femaleness—Akamatsu always returns to their position as object for sexual fetishment. This is really how most men (and a fair number of women) treat the real-life women who inhabit their lives, mixing sensible well-regard with a careless desire to sexualize without consequence. That Negima does this so blatantly deserves, I think, at least bookclub-level consideration; and while Akamatsu may not have intended any net good from his creative decisions along these lines, I think the opportunity here for the reader to critically examine their own understanding and treatment of the female person is worthwhile and should not be overlooked in the face of disgust for the surface of objectification.

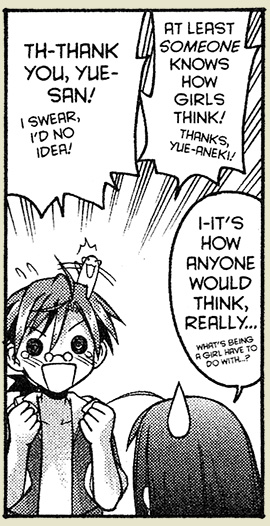

What's being a girl have to do with...?

What's being a girl have to do with...?

The most curious thing about Negima is that Akamatsu first establishes his female characters as sexual objects and then reestablishes them as non-object persons. And while he ping-pongs between their object and non-object states (sometimes within space of a single panel), the title's final statement is in support of these women not as objects but as wonderful, full-fledged characters. This is not to justify the book's rather gross and awkward use of sexuality, but to merely recognize its complexity.

And now because we all77nudge nudge wink wink approach texts containing disagreeable content with a sense of nuance and find ourselves able to appreciate quality and value even while disapproving of aesthetic or moral deficits, let's talk about what makes Negima something I rate well despite my deep conflicts over the book's material.

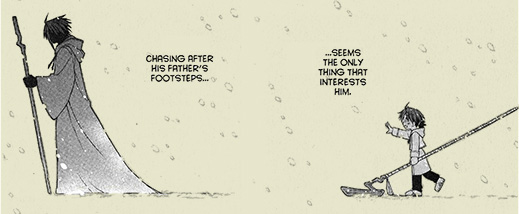

I've already mentioned Akamatsu's character work, but here are some specifics. Negi, the book's hero, is only ever okay. He's a bit of a Mary Sue but never really gets in the way of the book's true characters, the students. Negi begins the book as a fledgling magician, fresh from the academy and ready to prove himself. He's rather singleminded and so as much as he takes his role as teacher (and eventually protector) to these thirty-one girls seriously, he always struggles with his need to prioritize his true goal of locating his missing father. He's self-sufficient, self-reliant, and self-absorbed. If his character has an arc, it's wrapped up in his struggles 1) to put his students first and 2) to learn to rely on the powerful, wise, and intelligent friends who are happy to help him out.

But at least this happens at one point, right?

But at least this happens at one point, right?

But as I've implied, Negi may not even really be the main character in his own book. It's fun to watch him grow up a bit, even if he never really has to strain to do so. The real protagonist is his class of thirty-one girls. While the book seems to think it's the story of how Negi becomes the Best Wizard Ever, actually sitting down and reading the thing it becomes clear that this is really the tale of a bunch of girls who gradually discover the world is full of magic and how they'll interact with that knowledge. And while, as a class, there's never really any grave conflict over these girls' acceptance of the magical world (and a character arc with no conflict is generally dimly viewed under most rules of narrative critique), the charm of the individuals who make up Negi's class is so winning that it's hard not to consider their story worthwhile.

The girls are varied in temperament, skills, backgrounds, interests. Asuna has mysterious abilities and amnesia. Evangeline is centuries old and has millions of dollars in bounties on her head (and a crush on Negi's father). Nodoka is bookish in the extreme and her primary skill seems to be her courage in overcoming her shyness. Another girl is Negi's descendant from the future. Another is trying to be a good gymnast. Another wants to draw manga. Another died in 1941. Another is a scientist. Another is a chef. Another is a robot. Another is an orphan adopted by the church. Another has trained for years to protect the life of another student, who is the headmaster's grand-daughter. Only a handful of these girls have full arcs, but out of the thirty-one, each gets narrative spotlight for at least a short time and most are given distinct personalities and stories. That by series' end I can identify and tell you about almost all of them is, to me, pretty amazing.

Despite the title's rocky start, most of the stories end up being a lot of fun. After two volumes, I had given up on the book. Negima, in those volumes, just seemed an endless stream of disconnected school-daze stories and excuses to showcase nude teens. I took a long break from the series and then somehow got the third volume (maybe from the library). That volume was a distinct step in a better direction. The entire volume presents a single narrative arc (prior volumes never had stories longer than two chapters) and introduces the first hints that there might be some driving story behind the series. Volumes four through six offer a still longer arc and build more characterization and history into the series. As well, the fan service gets scaled back a bit, allowing the story to breathe on its own merits. By this point, I was invested enough in the story and characters that seeing where they'd go convinced me to stick with the series.

Akamatsu seemed to have trouble deciding what kind of series Negima would be. The first couple books seem to aim for Harry Potter crossed with harem comedy. After volume two, however, the harem aspect is relegated to occasional filler episodes scattered across the thirty-six remaining volumes. With volume three, the series seems to transform into supernatural adventure. Then, around volume eleven or so, the book becomes a tournament book for about three volumes. Then it becomes an otherworldly adventure, then tournament book, and then a kind of world-shattering epic adventure. Scattered throughout are chapters that seem to want to transform the book into a romance comedy. If the reader pays too close attention, a kind of literary whiplash may result, prompting frustration in those who want the book to be a single thing. Personally, I found the constant evolution of the series endearing—as it's hard to stay mad at the mistakes when the status quo is shattered with such alacrity and ease.

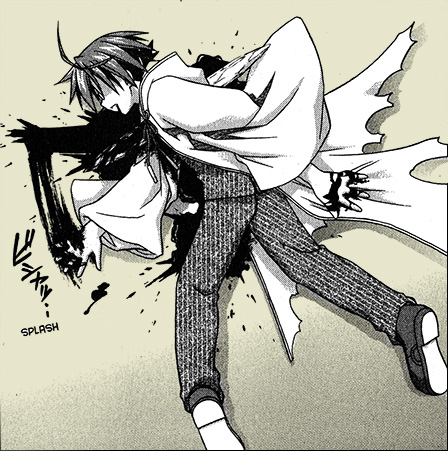

Annnnnd: fight.

Annnnnd: fight.

There remain a couple more things to talk about. Foremost perhaps, if one can minimize concern for the book's sexuality, most readers will want to know about the title's premature conclusion. For reasons I'm not yet aware of, Akamatsu elected to end the series before the principal story actually wrapped. The conclusion is moderately satisfying. With chapter 353 (of 355), all the story points are tied up save for Negi's quest for his father. This was the reason behind Negi's entire mission and so it's kind of the most important piece of the story. Chapters 354 and 355 zip the reader ten or more years into the future to a reunion of Negi's classmates where we are given a brief summary of how Negi's quest concluded. The series ends with an epilogue giving biographical synopses of each of Negi's students. It's a little bit underwhelming—but less so if one considers the series to be the story of Negi than that of his students. It's problematic, but could be worse.

The other thing is the sexuality. I've talked about it a bit already, but it may be worthwhile to discuss the age problem just a bit.

These girls are 14 and 15 years old according to their plot points and so, by fetishizing them, Akamatsu promotes a sort of statutory objectification. But then again, not really? These girls don't carry the awkward sexuality, physical proportionality, or carriage of a young teenager, but are instead mature women that the plot simply decides must be junior high students.88The exceptions are girls like Nodoka who, for reasons that also demand a good bookclub discussion, are more representative of the common young teen's figure and don't display the ballistic-level self-confidence that these other girls do. That Nodoka is the first to admit to falling head-over-heels in love with ten-year-old Negi must have some relation to her physical state. Perhaps her more modest proportions mean readers will find her pedophiliac ardor less threatening when compared with that of most of her classmates—though honestly the book seems written for a demographic that wouldn't be bothered by the implications. Still, no matter how old these girls appear, Negima encourages the readers' acceptance of them as junior-high-aged (even while confusingly depicting them as being much older).

I'm conflicted on this point somewhat. I think it's good to recognize that women, even young women, are sexual beings as much as anyone else—that they might have all the desires, curiosities, and kinks that you may have and plenty you don't. Negima recognizes that and pursues it (doggedly). The problem of course is that it does so with a camera lodged distinctly and completely within the cleft of the male gaze. Akamatsu presents strong female characters that are sexual and don't (often) apologize for their sexual natures—but he does so with the goal of titillizing his male audience (at least I presume his motive and audience here). It's one thing to present a mature and thoughtful depiction of a woman and her natural appetites. It's another to do so in order that a man can turn that woman into a sexual object. Too much, I'm afraid, Akamatsu's work is fueled by this latter prompt. And whether that's his intent or his editors', the result is pretty gross and kind of reprehensible.

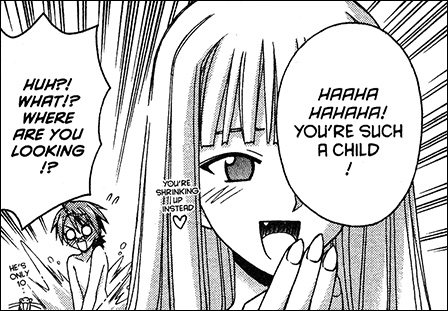

The girl here remarking on Negi's small penis is hundreds of years old but trapped in a ten-year-old's body.

The girl here remarking on Negi's small penis is hundreds of years old but trapped in a ten-year-old's body.

As I've suggested, it's rare that a single ideological element (or even a collection of such elements) is enough to cause me to judge a book's quality in one way or another. Case in point: I grew up in the '80s in an Evangelical Christian home—one in which my mother confiscated my Dungeons & Dragons books because, you know, devil's work.99To her credit, she reimbursed me for the books that I had spent so much money on. I, like many of my peers of the era, trashed my Metallica and Oingo Boingo because that's what Christian kids did—because, you know, the devil. As a full-fledged addict of comics, I would have performed the ritual sacrifice of many innocent animals for a Christian comic that was anywhere within a hair's breath of good. If an agreeable ideology was enough to bend my tastes, I would have owned at least one Christian comic book. But I didn't because ideology (whether joyfully in agreement or abundantly antagonistic) cannot hold court over the question of quality. A bad book is a bad book whether it says things I like or not. A good book is a good book whether it says things I like or not. And Negima, despite the fact that I justly hate some of it, is a good book. Its characters are lovely and endearing. Its story is often thrilling and emotional. Its art is dynamic and crisp. And that I'd gladly read another thirty-eight volumes with these girls just to watch them continue their personal evolutions is, for me, a big deal. I may not recommend it and I may feel some embarrassment for owning it, but it is a good book.

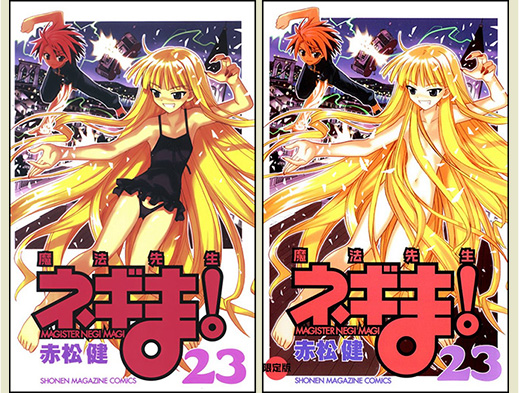

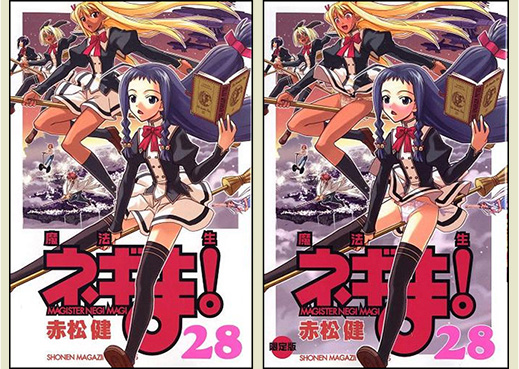

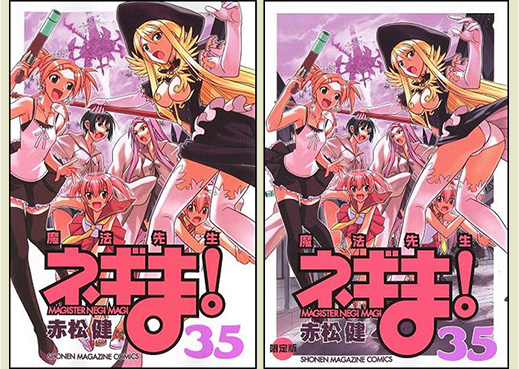

A Note on Covers

As I was finishing up writing this review, I remembered another evidence of the title's general misogynistic atmosphere. I'm not certain if it was for every cover, but at least for a good number there were offered special edition variants that depicted the series' heroines in more pointedly sexually objectified states. Here are four examples (the first is of the hundreds-year-old vampire trapped in a ten-year-old body).

That these are not available in the American edition does not alter Akamatsu's or the publisher's responsibility for bringing such things into the world.

Good Ok Bad features reviews of comics, graphic novels, manga, et cetera using a rare and auspicious three-star rating system. Point systems are notoriously fiddly, so here it's been pared down to three simple possibilities:

3 Stars = Good

2 Stars = Ok

1 Star = Bad

I am Seth T. Hahne and these are my reviews.

Browse Reviews By

Other Features

- Best Books of the Year:

- Top 50 of 2024

- Top 50 of 2023

- Top 100 of 2020-22

- Top 75 of 2019

- Top 50 of 2018

- Top 75 of 2017

- Top 75 of 2016

- Top 75 of 2015

- Top 75 of 2014

- Top 35 of 2013

- Top 25 of 2012

- Top 10 of 2011

- Popular Sections:

- All-Time Top 500

- All the Boardgames I've Played

- All the Anime Series I've Seen

- All the Animated Films I've Seen

- Top 75 by Female Creators

- Kids Recommendations

- What I Read: A Reading Log

- Other Features:

- Bookclub Study Guides