The Moon Moth

Created by: Jack Vance and Humayoun Ibrahim

Published by: PUBLISHER

ISBN: 1596433671 Amazon

Pages: 128

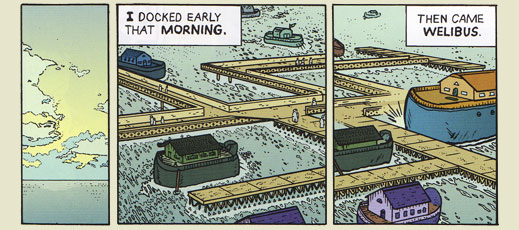

On Sirene, everyone who's anyone drives their own Noah's ark

On Sirene, everyone who's anyone drives their own Noah's ark

(minus the two-by-twos of course)

Generally, the purpose of setting a story in a science fiction world meanders down one of two lanes. On the one hand, an author may hope to introduce in the reader's mind a critique of contemporary society, culture, or history by forcing a comparison of analogy. A Brave New World, 1984, Gattaca, Solaris, even Alien—these are stories whose goals are above and beyond the simple entertainment of the reader. These follow in the grand science-fiction tradition of giving readers easy tools with which to evaluate the current world-state by stripping the contemporary situation of its context. It's a time-honoured and noble pursuit.

The other option, less praise-worthy perhaps, is the simple use of science-fiction elements to decorate well-worn stories and make them seem fresh or exciting. Star Wars, Predator, Treasure Planet, E.T., Aliens, or Back to the Future—there's nothing wrong with these stories in principle. They're fun and adventurous and make for an invigourating experience; but they're not exactly stories that couldn't exist successfully in non-science-fiction terms.

I have not read the works of Jack Vance—this Moon Moth adaptation is my introduction—but I hope his other works slide so neatly from these alternating taxonomies as well as The Moon Moth does. This isn't a work by which we examine our present culture's social ills; neither is it predictive, extrapolating out from some forseeable future. And it doesn't even so much dance a thrilling adventure epic to save the world from the A.I. threat or span galaxies to watch the combat of empires unfold. It probably wouldn't make a great film (though a great film might be set in these fascinating climes). Instead, The Moon Moth seems more a development of possibilities solely for the sake of deducing the directions they might take a people.

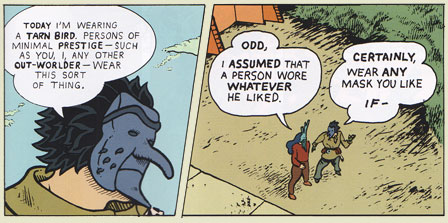

The particular investigation at stake here is the quality and means of social communication if a civilization were to develop along a different, perhaps more elegant, vector. On Sirene, the world central to The Moon Moth, conversation is blatantly far from equitable. All discussion is embellished, pronounced, and finally given meaning through the use of instruments. Each instrument has a particular purpose, a goal through which status and intent is communicated. One instrument may convey wrath to a lesser member of the social hierarchy, while another when properly used may convey polite obsequience to a person of superior standing. Only the slave caste sings conversations unaccompanied by instrumentation, and that is a bare mark of their low station. Further complicating matters each citizen wears a mask, the make of which further codifies social station and directs which instruments should be played in conversation with each other citizen.

All interactions on Sirene are conducted according to the concept of personal honour. There is no currency beyond one's personal honour—or more properly, what personal honour one may convince others he possesses. A citizen may wear a grand mask if he has the honour to pull it off. A citizen may take goods of the finest craftsmanship if he has the honour that would allow him to do so. On Sirene fortune favours not merely the bold however, for overstepping one's honour may lead to a speedy decapitation. Foreigners, then, are at a distinct disadvantage on this world, and being an offworlder ambassador would be a trial of great magnitude for even the most quick-witted diplomat.

The Moon Moth is constructed as a sort of thriller, engaging a not-so-quick-witted ambassador as he tries to unearth a murderer whose face he cannot know—after all, on Sirene we all wear masks and may change our masks at will so long as we can keep up with the demands of the masquerade. While there is some excitement over protagonist Ser Thissel's dilemma as he tries to detect a man who may be undetectable, the plot is not the book's central joy. This is good because that avenue is rather thin and even as the narrative turns to its final twist, we recognize that the story may have only ever been an excuse for us to engage Vance's strange, intricate world. I was fine with the story, but Ser Thissel (nearly incompetent for much of the book) and reaching the climax were never my motivations for remaining in The Moon Moth's grip.

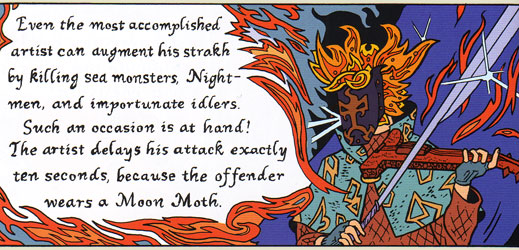

Vance and his adapter, Humayoun Ibrahim, have crafted a world that I've returned to over and again in thought over the several weeks since reading The Moon Moth. Not only is Vance's world fascinating, but Ibrahim's visual translation of the instrumental idea leaves me wondering how the story could have ever succeeded in bare prose. While I generally found Ibrahim's figure-drawing a weakness, the manner by which he effortlessly demonstrates both the instrument being used and the technical proficiency with which it is being played is so winning that I can hardly imagine the story in any other form. Comparing Ser Thissel's lurching melodic incompetence with the natural musicianship of Sirene's natives is caught by readers at a glance and the story's purposes are never hindered for lack of craftsmanship on this score.

In case you missed it, he's playing a violin with a sword. Badass!

In case you missed it, he's playing a violin with a sword. Badass!

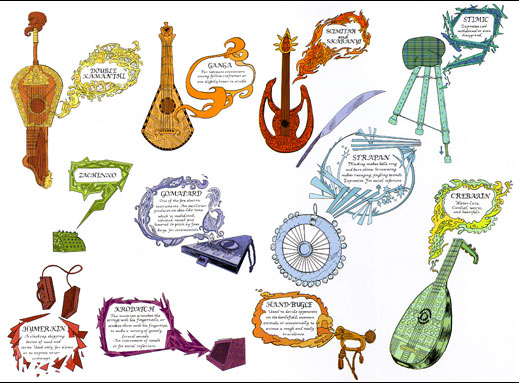

There are some bumps to the road, however, the chief of which is the natural difficulty in translating a foreign language for readers in such a way as to make the text flow effortlessly. Because The Moon Moth is chiefly concerned with the exploration of a music/status based language, converting that simply to wholly verbal expression would be inadequate. There is some learning curve demanded of readers and Ibrahim does what he can to help by providing at the book's frontmatter a visual glossary of several instruments, the sounds they make, and the social implications of using each instrument. For the first few exchanges readers will doubtlessly be turning back to this glossary as an aid to understanding. Due this break in the reading rhythm, one's first experience of the text may feel staggered and a bit too staccato. I felt some of this myself but found a second reading to be far less punctuated and discovered a rhythmic sense that I missed on my first read-through.

This is basically like the inside cover of Vietnamerica that you keep flipping back to so you can tell who's who throughout the story

This is basically like the inside cover of Vietnamerica that you keep flipping back to so you can tell who's who throughout the story

I'd be tempted to understand that kind of difficulty in the reading experience as a knock against the work, but in The Moon Moth's case I think the complexity of the idea merits the work it requires of the reader. As I said above, I've come back again and again over the intervening weeks to the concepts Vance and his interlocutor present in this small book. It's such a fascinating excursion into what makes a language and how language can direct a people that I can't help but enjoy it, despite any initial reservations I may have held. Ibrahim presents a colourful, intricate world—one only partially of his own making, but one worth our time nonetheless.

Good Ok Bad features reviews of comics, graphic novels, manga, et cetera using a rare and auspicious three-star rating system. Point systems are notoriously fiddly, so here it's been pared down to three simple possibilities:

3 Stars = Good

2 Stars = Ok

1 Star = Bad

I am Seth T. Hahne and these are my reviews.

Browse Reviews By

Other Features

- Best Books of the Year:

- Top 50 of 2024

- Top 50 of 2023

- Top 100 of 2020-22

- Top 75 of 2019

- Top 50 of 2018

- Top 75 of 2017

- Top 75 of 2016

- Top 75 of 2015

- Top 75 of 2014

- Top 35 of 2013

- Top 25 of 2012

- Top 10 of 2011

- Popular Sections:

- All-Time Top 500

- All the Boardgames I've Played

- All the Anime Series I've Seen

- All the Animated Films I've Seen

- Top 75 by Female Creators

- Kids Recommendations

- What I Read: A Reading Log

- Other Features:

- Bookclub Study Guides