In Clothes Called Fat

[A note: this review will contain depictions of nude women from the work being reviewed. Discretion is left to the reader.]

The Ancient Near East was a land filled with gods and cosmologies at war with all others. The inhabitants of every nook and cranny had their own deities and their own religious customs and their own emphases. And as with the religions of today, the zealous devotees of one god were not particularly interested in tolerating the gods of their neighbours. It made sense for a culture to have a god different from that of a neighbouring culture—after all, if you wished to war with and then absorb a neighbour, it didn't make much sense to pray to a god you both worshipped and/or served. Gods of seas, gods of rivers, gods of land, gods of fire, gods of sky, gods of clouds, gods of rain, gods of sex and of war and of death and of life and of alacrity. Take your pick. Different gods for different needs. And all the different practices that go along with those needs.

Still, almost across the board in the Ancient Near East, there was a great commonality. These gods received some form of visible rendition. Idols proliferated. Carved images, painted figurines, metaphorical representations. It's probable that no Philistine actually thought Dagon looked like a hybrid between a fish and a dude, but people need something to hold on to, a little prop to turn mere metaphor into something vaguely solid and believable. But not the people of Israel. Their god, Yahweh, disallowed physical representation of deity (we even see this carried forth into the Islamic antipathy toward the visual expression of Moses, Jesus, Mohammed—and really, any of their prophets). The thing was: Yahweh was considered too vast and magnificent to be represented by something as inarticulate as an image. When the Israelites were cursed at the foot of Sinai for building a golden calf, it wasn't for following another god; instead, they had minimized Yahweh by creating a Yahweh-idol that magnified only his strength (what a calf was known for in that culture). The problem with the golden calf or bull was that it crafted an inadequate portrait of Yahweh.

FYI: The images in this review read right-to-left, the Japanese way!

FYI: The images in this review read right-to-left, the Japanese way!

And that's the trick. Art objectifies its subject. Inherently.11And actually, literally, while we're at it. The nature of illustration, of painting, of cartooning is to take things—whether animal, vegetable, mineral, or ideal—from their multifaceted, multidimensional, highly nuanced reality and smash them down into a flat, inadequate representation of their actual selves.

But we're generally okay with this because, thinking people that we are,22Even if only on a subconscious level much of the time… we recognize that the intention of objectification is not to explore with ultimate depth and patience the full expression of the object of our objectification. When I draw a woman or a chair or a political ideology, I can reasonably only investigate a fractional portion of her/its multitude of properties. If I draw a Dollar Sign or the Uncle Pennybags33 or an Illuminati Pyramid With An Eye and call it "capitalism," you might get some sense of some portion of what I'm intending to describe about the economic ideology, but only that. And we're usually okay with this because we recognize that the work of art was never intended to entirely explain capitalism. We might object to what I've said about capitalism, but our objection will always be because we think the aspect represented was poorly described, not because we expected the representation to entirely explore or explain the theory.

or an Illuminati Pyramid With An Eye and call it "capitalism," you might get some sense of some portion of what I'm intending to describe about the economic ideology, but only that. And we're usually okay with this because we recognize that the work of art was never intended to entirely explain capitalism. We might object to what I've said about capitalism, but our objection will always be because we think the aspect represented was poorly described, not because we expected the representation to entirely explore or explain the theory.

In the present circumstance in which the world finds itself circa the beginning of the third millennium AD, sexual objectification (esp. of women) has come under particular scrutiny—not so much because of its nature, but because the context in which it occurs plays into a harmful societal condition leading generally to a misogynistic culture that renders the female experience of life particularly less readily enjoyable than the male experience of the same.44In the same way that the group of kids who will get stung by bees at birthday parties can be said to have a less enjoyable experience than the group who doesn't get stung—even if through luck, circumstance, and outlook the bee-stung kids eventually happen to experience more joy at said parties unrelated to the bee stings.. There is nothing exactly insidious about the objectification of women in and of itself. As art the Mona Lisa is inherently an objectification—though not one we readily recognize as being harmful. The problem, then, is twofold: 1) the overwhelming singlemindedness in the tendency to reduce women for objectification along a single vector (sexual availability); and 2) the tendency for the members of the contemporary society to forget that objectification is meant only to convey a narrow portion of the object's properties thereby allowing that narrow perception to govern the conception of the whole.

In short, women are largely and forcefully objectified along sexually titillating lines and the consumers of that objectification begin to perceive women wholly through sexual filters, breaking the tacit agreement that objectification is only meant to convey limited facets. This breach of the normal experience of objectification (say, the kind we comprehend easily when viewing a child's drawing of a cactus or a dog) actually meets up well with the trouble Yahweh had with objectifications of his own self. In portraying Yahweh as a calf, a symbol of strength in the Ancient Near East, the fear was that his Israelite worshipers would begin to view him wholly as a a deity of bullish strength (much as the fire-and-brimstone preachers of legend gleefully viewed the Christian god principally as a being of wrath and terror). So the tendency of people to break the good-faith agreement between the objectification and the object is not new, and special care must be taken in the dismantlement of the problem.

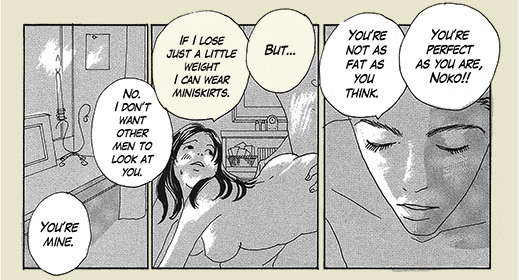

Moyoco Anno's In Clothes Called Fat intimately concerns a world maintained and partly governed by the sexual objectification of women and reads as a good companion to Kyoko Okazaki's Helter Skelter. The book revolves wholly around how the principal identity of a woman is founded in her attractiveness. Every new chapter (save for the finale) is abstractly heralded by the depiction of a lean, beautiful, and often nude woman—who is not (until the last chapter) the protagonist. The entire ecosystem of Anno's story is populated by an ethos and ethic developed around the desirability of women.

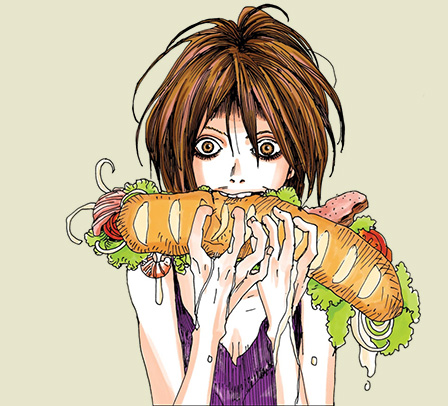

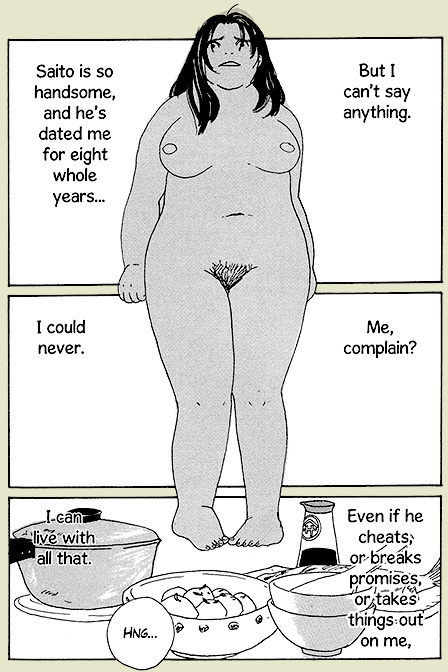

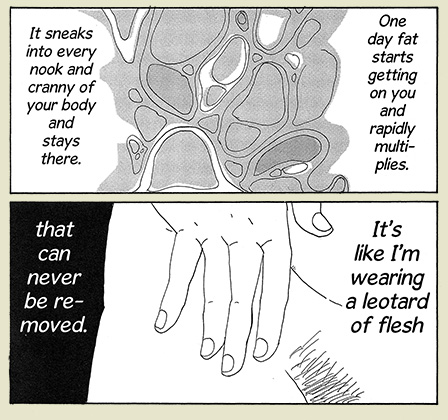

Noko is fat. She works in a business office, has a small taste of office social life, and keeps a handsome longterm boyfriend. But she is definitely fat. And while Anno's portrayal of her obesity waxes and wanes, she is defined (and irrevocably so) by her weight. Early on, she deliciously describes herself: "It's like I'm wearing a leotard of flesh that can never be removed." Her position with regard to her social circle, female co-workers, boss, and boyfriend are all exactly circumscribed by the way she looks. She lives in a world where the sexual objectification of the female has run amok. That is, of course, to say: she lives in a world crisply reflective of our own.

I'm not certain of the intricacies of Japanese culture and how measured their reaction to an obese woman would be, but while the American reaction (probably) wouldn't be outright bullying outside the cesspit interactions of YouTube and online forums, her measure as a woman would certainly be underlined and calcified by her weight. We value women in accord to their attractiveness. We believe that a woman can have use without looking good, but we're more willing to believe her useful if she's attractive. And then if she is attractive, we're more willing to forgive her inadequacies. In this manner, In Clothes Called Fat reflects even the American ideologies pretty well and should make for a fairly seamless read for the Western reader.

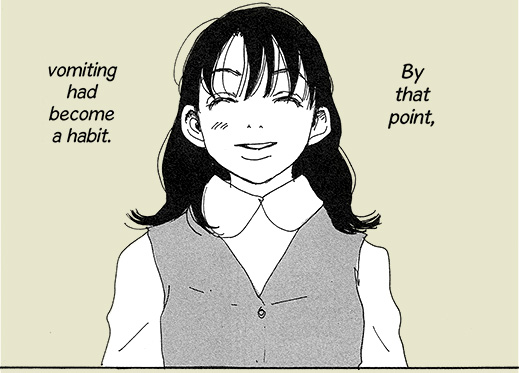

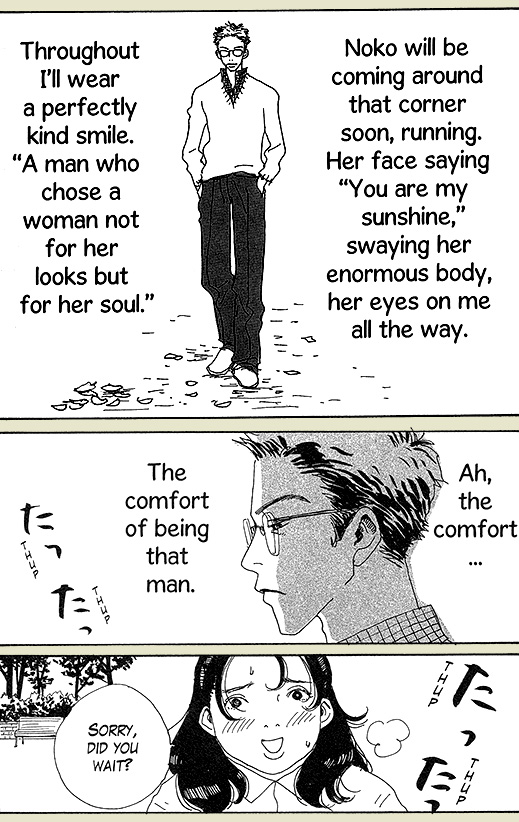

Anno delves into the experience and mystery of the culture's fascination with beauty through unsparing episodes from Noko's life. Her sex life, the bullying she experiences at work, her abortive attempts at self control. Noko is victimized by her own lack of self-confidence and inability to truly grasp the manner of the world about her. A dietician describes Noko: "Her soul is obese." Anno allows the reader to dwell in Noko's thoughts, giving us insight enough into the protagonist's sense of the world and herself.55 In an interesting turn, Anno presents three other minor point-of-view characters (Mayumi, Noko's antagonist co-worker; Saito, Noko's boyfriend; and Kiyo, Noko's dietician), allowing the world to be fleshed out in still more interesting ways.

The principle conflict seems to be the question of whether Noko will be able to lose weight, thereby gaining confidence and a place in society, but Anno is canny enough to avoid a problem/solution pairing so pedestrian. Instead, In Clothes Called Fat wonders if it really is the clothes that make the man, postulating instead that no woman can successfully survive the ravaging of society and escape with her true self intact.66 It even hints that men too are damaged by the sexual objectification of women by temporarily engaging Saito's personal struggles and inadequacies, completely invisible to Noko.

Visually, In Clothes Called Fat engages Anno's theme through the ready visual objectification (and sexual objectification) of its characters. Noko spends substantial time in the narrative naked, often having sex and one time having her body poured over and lusciously examined by a paramour. Mayumi too is forcefully depicted as almost pure sex appeal and her identity is determined by her fulfillment of the male sex fantasy. Anno's figurework resembles the loose grotesques present in Kyoko's Okazaki's books and whether intentional or not, this works to diffuse much of what would otherwise be titillating in the book. Both Noko and Mayumi are thoroughly and consciously rendered as sex objects, but we can almost immediately understand it as holding narrative heft (as opposed to much of what we've come to expect from the depiction of women in the visual arts).

This is not a relishment in sexual objectification but labours instead as an indictment of it.77Which is totally the kind of thing that a lot of untalented, thoughtless sexual objectification pretends to attain. By the epilogue, we are neither pleased nor amused by the ends of any of the characters nor in the circumstances that prompt those ends. We do not enjoy or approve of Noko's closing determination, but we can understand her resignation because we're neither stupid nor blind to the way of the world.

In Clothes Called Fat does that thing the best books do. It prompts renewed thoughtfulness about the world, the nature of civilization, and our place in both. We shouldn't expect that Moyoco Anno will change the world with this small graphic novel, but we might as well hope. And at the least we can allow ourselves to be affected and renovated.

Good Ok Bad features reviews of comics, graphic novels, manga, et cetera using a rare and auspicious three-star rating system. Point systems are notoriously fiddly, so here it's been pared down to three simple possibilities:

3 Stars = Good

2 Stars = Ok

1 Star = Bad

I am Seth T. Hahne and these are my reviews.

Browse Reviews By

Other Features

- Best Books of the Year:

- Top 50 of 2024

- Top 50 of 2023

- Top 100 of 2020-22

- Top 75 of 2019

- Top 50 of 2018

- Top 75 of 2017

- Top 75 of 2016

- Top 75 of 2015

- Top 75 of 2014

- Top 35 of 2013

- Top 25 of 2012

- Top 10 of 2011

- Popular Sections:

- All-Time Top 500

- All the Boardgames I've Played

- All the Anime Series I've Seen

- All the Animated Films I've Seen

- Top 75 by Female Creators

- Kids Recommendations

- What I Read: A Reading Log

- Other Features:

- Bookclub Study Guides