Ichiro

One of the more recurrent themes of young adult literature is disorientation. A young protagonist one day wakes in an unfamiliar place and—through a variety of struggles and trials—eventually overcomes the cultural hindrances that hold him back. Or a young protagonist's home is destroyed and she, alone and unprepared, must discover and come to control the wildness of the greater, wider world around her. Or a young protagonist arrives at a new school (perhaps even mid-term) and must learn to swim in the new, strange waters of his new social ecology. These are common stories—common enough that we probably don't need names or titles to prompt us to fill in some of the details about how these things will work out.

But what if that sense of disorientation, that alienation, didn't give way to heroic success and comfortability? What if the story was less about success in a strange place than it was about acquiescence in the face of an inescapable foreignness, an otherness that cannot be overcome because its alien nature was too great. In a way, that's the kind of story Ryan Inzana explores in Ichiro. It's a book where success is measured not in fighting against disorientation but more in simply coming to apprehend that feeling and taking what ambiguous lessons one can from it. For this, despite the book's certain indebtedness to fantasy and folklore, it may actually be a more realistic story—and hence more valuable to the young reader.11It may be slightly presumptuous to describe this book in terms of YA lit, as I haven't seen that taxonomy prescribed elsewhere. The jacket and indicia give no clue to how it should be catalogued. I only lean toward YA because the protagonist is a young teen and is fraught with young teen concerns. Ichiro, like all good YA lit, can be enjoyed by adults as well as young adults.

This kanji apparently means "yellow" for whatever reason. Or something. Don't ask me, I can't read kanji.

This kanji apparently means "yellow" for whatever reason. Or something. Don't ask me, I can't read kanji.

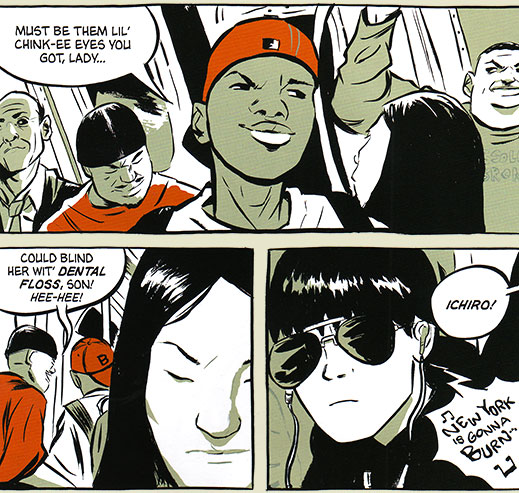

Ichiro and Ichiro survey through several layers of disorienting strata, investigating and coming to terms with vertiginous environmental, historical, and political paradigms. Inzana's protagonist is introduced immediately at the mercy of two common circumstantial troubles, as well as a third—this one less common but unfortunately by no means rare. In the first place, Ichiro is a young teen, which naturally places him at odds with every other living being (for even the best of us, traveling through puberty is an awkward journey—with our ungovernable bodies controlling us rather than being controlled by us). On top of that: Ichiro, the son of an American father (of indeterminate heritage22Ichiro's father is at least a portion Westerner as Ichiro's grandfather, Benny, appears to be the typically ethnocentric Caucasian American. Although... the art is unclear as to whether Benny is Anglo, Italian, Jewish or of any other nationality. It's even possible that Benny could be a Japanese man whose hair had lightened with age and whose attitudes may have been shaped by the same media projections that too often capture the hearts and minds of the average American.) and a Japanese mother, is hapa. Because he has Asian physical characteristics, even in a city so cosmopolitan as New York, Ichiro has to endure the stereotypical racist reactions that in America still haunt those of Asian descent. Even in his home country, Ichiro is made to feel a foreigner. He hides his eyes behind thick, dark aviators and his personality behind loud, angry music. He projects the ethos standardized across the disenfranchised American youth. Both of these are environmental and ontological struggles that must be endured rather than overcome. And while we all grow out of teenagerness into whole new insecurities, ethnic identity is as much the response of others as it is a projection of our own.

I mean, it will of course.

I mean, it will of course.

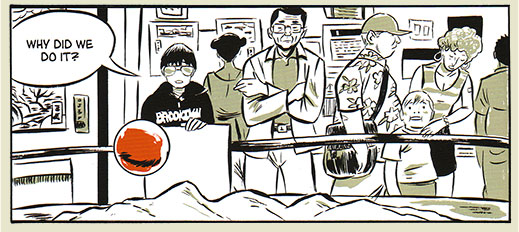

The third threat to Ichiro's comfortability in this world may be built of melodrama, but it fits the story well enough. Ichiro, by military accident, is fatherless. He wasn't abandoned so much as he was de-fathered. Remembering his father nearly only in dreams—a silent, almost ominous figure for much of the narrative—Ichiro is set at a heavy disadvantage so far as male influences go. While his dad (obviously enough) was world-friendly and adept enough at adapting to other cultures, Ichiro's grandfather Benny is characterized by the worst American ignorances. He's loud, boastful, and builds his interactions with the world off bias and presupposition. And so, Ichiro threatens to follow suit.

Ichiro, at story's beginning, is a lost boy—and the storm into which he will soon be drawn doesn't promise to make finding his way any more likely. At best, Ichiro may discover himself better able to orient along his life's current, but he will only ever be carried where the rivers of fate will move him.

While Inzana sets Ichiro in the midst of a shaken, uncertain world, the author quickly moves him into much more disorienting worlds. If New York didn't understand him, at least he somewhat understood it. Or at least his place in it. Japan is quite another animal and beyond a presentable-though-obviously-foreign use of the language, Ichiro is a fish out of water. A fish out of water out of water. He vastly prefers America and holds onto the national arrogance that his Grandpa Benny built into the lens of Ichiro's foreign policy. Still, living with his Japanese grandfather will only serve to cause further disorientation, further disillusionment—though with his Asian grandfather's help, Ichiro may come to recognize that this kind of alienation from expectation is actually the common human experience throughout life. Perhaps his mother and both grandfathers are continually experiencing this at-odds-with-the-world experience as well. And maybe it's the way you deal with the fear that these experiences create—maybe it's your reaction that will prove what kind of a person you have been raised to be.

Mostly because we didn't see them as human. We were not great people.

Mostly because we didn't see them as human. We were not great people.

Ichiro's grandfather is way more charitable than me.

Ichiro can be a powerful, thoughtful work—an evaluation of what it means to be a human trapped by the arbitrary structures inherited by the capriciousness of birth. Male or female? Rich or poor? Red or yellow, black or white? American? Japanese? Ugandan? How are we responsible for the state into which we are born? Ichiro, among its other conceits (for instance, a decent story with well-crafted art), can give us a framework by which to better evaluate the existence we have been pushed into. It's not the path of victors, but it proposes something better than living as one of the conquered.

Note

I hadn't mentioned it, but a good portion of Ichiro—perhaps a full third of the book—takes place in a world of myth and magic reflecting traditional Japanese creation legends. Ichiro is drawn into this mythic world as much by his own volition as he was when when born into our own. It was not by his choice and he is as much at the mercy of that foreign environment as we each are of our own worlds. Ichiro's time in that fantasy realm seems to function primarily as a filter through which to understand his real-world struggles. It's a parable of sorts, and more or less works. As with Miyabe's Brave Story, I preferred the real-world side of the story to the myth-world side, but I do appreciate Inzana's purpose.

NOte: Word balloons in pale yellow-green are in Japanese. In white are English.

NOte: Word balloons in pale yellow-green are in Japanese. In white are English.

Other Note

I'd seen several reviewers describe Ichiro as manga. The appellation is baffling to me, no matter what sense you choose to honour for the term manga.

- If manga means "Japanese comics," it is unsuitable here, for Inzana is American.

- If manga is meant to refer to a certain genre of comics, then it also seems an inane description as it follows none of the stylistic tics commonly associated by Americans as being hallmarks of "manga"—big eyes, speedlines, chibi versions of characters, sweatdrops on the backs of heads, and interminable fights punctuated more often by inner monologue than by actual action. Visually, Ichiro is composed in a manner very consistent with Western comics culture—save for when Inzana homages traditional Japanese arts. In fact, his work looks reminiscent of that of GB Tran.33And yes, I realize how ironic that might sound, but Tran (while of Vietnamese heritage) was born and raised in America (cf. his wonderful recountment of his recent family history, Vietnamerica).

- If manga simply means "comics," as it does in Japan, then the appellation is worthless in an English context because our word for comics is comics.

It's possible (i.e. likely) that reviewers' use of manga to describe Inzana's book is a serendipitous intersection between 1) the narrative state of alienation that Ichiro experiences and 2) a similar state which Inzana himself almost certainly experiences to greater or lesser degree (cf. Gene Luen Yang's American Born Chinese). So I guess, in some sense, we can cheer the awkwardness created as an object lesson in support of Inzana's work.

Good Ok Bad features reviews of comics, graphic novels, manga, et cetera using a rare and auspicious three-star rating system. Point systems are notoriously fiddly, so here it's been pared down to three simple possibilities:

3 Stars = Good

2 Stars = Ok

1 Star = Bad

I am Seth T. Hahne and these are my reviews.

Browse Reviews By

Other Features

- Best Books of the Year:

- Top 50 of 2024

- Top 50 of 2023

- Top 100 of 2020-22

- Top 75 of 2019

- Top 50 of 2018

- Top 75 of 2017

- Top 75 of 2016

- Top 75 of 2015

- Top 75 of 2014

- Top 35 of 2013

- Top 25 of 2012

- Top 10 of 2011

- Popular Sections:

- All-Time Top 500

- All the Boardgames I've Played

- All the Anime Series I've Seen

- All the Animated Films I've Seen

- Top 75 by Female Creators

- Kids Recommendations

- What I Read: A Reading Log

- Other Features:

- Bookclub Study Guides