How to Be Happy

You wake up from the perfect night's sleep, your cycle having been monitored and corrected by the room's somnometer. You eat a refreshing morning meal, calculated to your tastes and nutritional needs. You're ready for a day of doing things both that you love and that will contribute to the society. You are healthy, rested, secure, and fulfilled. Life is good and you feel good about it. And it's all due to this wonder-filled civilization you've inherited, perfect in every way. You think. I mean, maybe there's this little nagging something at the back of your mind, but maybe there's not. It's not like you could tell—not with how amazing everything is.

I haven't read a lot of science fiction criticism—or really and honestly, any science fiction criticism—but I have to imagine the idea that utopia and dystopia are some kind of synonym is pretty commonplace. It's pretty facile on the face of it, the concept that any man-made paradise is going to suffer from ultimate problems that render it a false Eden. Whether a utopian society is such because of its citizens' willful ignorance of the flaws in the system (a la the Eloi in Wells' Time Machine) or because of its citizen's blithe willingness to exploit another group (a la Fritz Lang's Metropolis) or because of its fascist management of thought and speech (a la Vonnegut's "Harrison Bergeron")—whichever the case, because of the natural pluralism of the human community, our only access to utopia could ever be through a negligent imagination, a kind of naive carelessness.

Some of the less inventive works pick at the easy fruit of dystopia, presenting broken societies from the outset, worlds in which the inequities are both made obvious and then capitalized on from their earliest chapters. Hunger Games' inequitous Districts make for a recent popular example. Blade Runner, too, presents an amazing futureworld, but even from the opening credits we know that the high-science future is dirty and grim and awful. More intriguing by a margin are those books and films that explore a perfect world only to eventually find cracks that turn to crevices. These are necessarily going to be rare because a beautiful world without conflict makes for a boring story. And then there're the few books that present full-fledged utopias. I haven't read in the niche extensively, but they're difficult books to pull off—1) because story conflict has a hard time existing in a true utopia, and 2) because most readers will scoff at the author's naïveté.

Two interesting examples of straight utopian literature, both from Kurt Vonnegut, include Galapagos and "Unready to Wear." Galapagos entertains the high-concept of being narrated from billions of years in the future by a ghost from the 20th century who flits above a world in which our humanity has long been extincted and replaced by a kind of peaceful human/seal hybrid. The implication, of course, is that in order for humanity to arrive at anything resembling a utopia, it'd first have to quit its humanity. "Unready to Wear," an earlier work, prototypically explores the idea by positing an evolved humanity who have solved all of their problems by shaking off the sweaty, itchy, irritating bother of the human flesh. Again, humanity must become other than itself in order to have a hope of paradise.11Interestingly, the Christian story fits well enough with Vonnegut's cynicism toward the human endeavor and also demands humanity to evolve into something we wouldn't quite recognize as human—only a brave new species of humankind could ever traipse around a heaven or a new earthly paradise or what have you and not start a war within a year or a month.

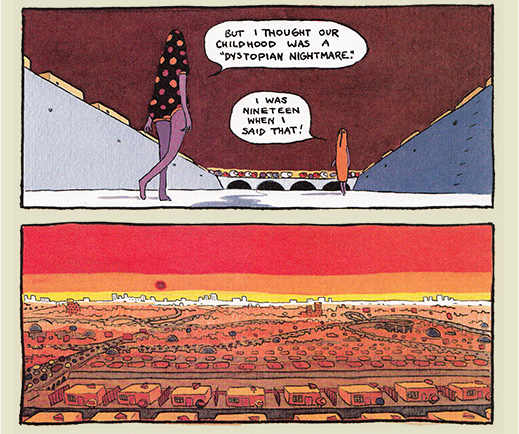

For her part, Eleanor Davis spends almost the entirety of How to Be Happy offering a delicious exploration of the tie between utopia and dystopia, between paradise and infernal paradise. It's a fine balancing act, funambulating between hope and despair, but she travels back and forth the distance with sure feet. On only two occasions amongst the collection of shorts does Davis overtly invoke the concepts of utopia and dystopia (once even going so far as to use the word dystopia itself), but for the most part she keeps the theme as mere atmospheric hum. One could be forgiven for not using the idea of earthly paradise as a governing filter for the work if it weren't for the book's title, How to Be Happy.

Utopia, the word, is derived from two pieces. The first, eu-, means "good" and sees itself in common English use in euthanasia and euphemism22Eu (good) + thanatos (death) = euthanasia, and is concerned with people dying a good or peaceful death with dignity.

Eu (good) + pheme (speak) = euphemism, the broaching of brute ideas via evocative but less volatile words, e.g. time of the month for menstruating.. The second, topos, means place and we see this term crop up in the cartographic practice of mapping topography. Utopia, then, is a good place, a kingdom of peace and security. Of happiness. A society coming to a place of peace via learning how to be happy is an essential piece of utopian presence. Without a general sense of happiness (no matter how broadly we define happiness) amongst the beneficiaries of a society, we have no utopia.

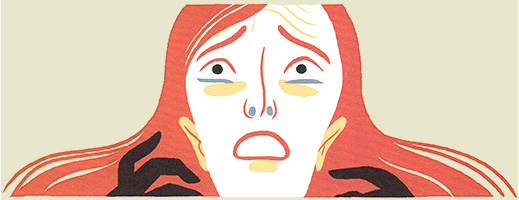

But while Davis occasionally speaks to the books' ruling concept in terms of societal shifts (especially in the second short, "Nita Goes Home," and on a smaller paleosocietal sense in the first story, "In Our Eden"), she mainly concerns herself with examining the attempts to escape dystopia in the detritus of much smaller-scale kingdoms. A boy seeks to perfect the world of his experience by maintaining ultimate control over a younger boy's interactions with him by a mix of psychological and physical aggressions ("Thomas the Leader"). A musician exercises a pacific effect over the animals of the wilderness through the sound of his guitar and seeks to bring an animal woman into his domain through the same tools, even against her nature ("Sticks and Strings"). A woman submits herself to the tutoring (governance) of a personal growth guru in order to find peace and joy in the world through tears ("No tears, No Sorrow"). In another, a young man becomes friends and more with a young woman because of his ardent interest in the woman's father, only to be discovered by the reader (in a perfect fourth-wall moment) capitulating to the woman's sexual advances in opposition to What He Really Wants ("Summer Snakes"). There are other stories, but the final narrative note seems to underscore the thesis (and echo in a way Vonnegut's solutions), suggesting that the human mind in its present state is the chief obstacle to utopia and we are better off freeing ourselves from its dystopic tyranny. She leaves the means to that end unstated and amorphous—whether by suicide or pharmaceutical intervention or altered mindstates or metaterrestial intervention—and the collection is probably more palatable for the ambiguity, because while we're happy to be given an inkling of her answer, the American way is to bristle at any lifestyle solution that is offered as anything close to an actual suggestion.

I was originally mildly disappointed in Davis' choice for the one-page final story, preferring the one-page story that immediately precedes it, a powerful and wonderfully conceived exhibition of perspectival shift that offers nearly the same conclusion, only slightly less overtly stated. After several readings, I'm satisfied that Davis' choice actually is the better ending in that it more succinctly ties together the disparate threads of her otherwise conclusion-eliding narrative pieces.

How to Be Happy appears as a dialogue or argument between a handful of ideologies unaware of each other's presence. They don't interact directly and orate as if theirs was the only voice in the room. Davis emphasizes this sense by illustrating many of these episodes using entirely different techniques and employing entirely different styles. One story appears as a colourful screenprint with absolutely no linework. The next could have been drawn with a Uni-Ball and features an oversaturation of watercolours. One has very detailed illustrations with strong negative space and sepia tones, another is washed and gentle with mysterious and lovely creatures, another is straight black-and-white with drawings that call to mind the childhood adventures of Nate Powell's Any Empire. And there's more. Davis is clearly talented and diverse. If one wasn't aware, it would be easy to mistake Davis for the collection's editor and the individual stories as the anthologic production of a number of artists.33I picked up How to Be Happy on the same day as I did Emily Carroll's Through the Woods. Both are short story collections, but the difference is striking by the proximity. Carroll's collection evidences a kind of evolution of style, but it is always obviously obviously Emily Carroll. There is no mistaking her work. Davis, on the other hand, plays all over the map.

This is my first encounter with Eleanor Davis and her work. I appreciated my time in her worlds. She offers plenty of food for the hungry of thought—even if thought may ultimately be the root of our troubles. Davis invites readers into realms of nostalgia and of mystery and of existential terror. The portholes through which we can view these kingdoms of hope and pain are small and smudged, but we see enough. Enough to apprehend them, enough perhaps even to judge them. And certainly enough to enjoy the experience of their lessons.

Good Ok Bad features reviews of comics, graphic novels, manga, et cetera using a rare and auspicious three-star rating system. Point systems are notoriously fiddly, so here it's been pared down to three simple possibilities:

3 Stars = Good

2 Stars = Ok

1 Star = Bad

I am Seth T. Hahne and these are my reviews.

Browse Reviews By

Other Features

- Best Books of the Year:

- Top 50 of 2024

- Top 50 of 2023

- Top 100 of 2020-22

- Top 75 of 2019

- Top 50 of 2018

- Top 75 of 2017

- Top 75 of 2016

- Top 75 of 2015

- Top 75 of 2014

- Top 35 of 2013

- Top 25 of 2012

- Top 10 of 2011

- Popular Sections:

- All-Time Top 500

- All the Boardgames I've Played

- All the Anime Series I've Seen

- All the Animated Films I've Seen

- Top 75 by Female Creators

- Kids Recommendations

- What I Read: A Reading Log

- Other Features:

- Bookclub Study Guides