The Hound of the Baskervilles

Created by: Ian Edginton and I.N.J. Culbard

Published by: PUBLISHER

ISBN: 1402770006 Amazon

Pages: 128

After an unsuccessful permanent hiatus (and killing off his great detective), Arthur Conan Doyle returned to Sherlock Holmes and penned perhaps his most famous of the sleuth's stories. The Hound of the Baskervilles was well-regarded and is still read by students and Holmes aficionados every year. I, however, have never read the book and approached this adaptation in near total ignorance. As mentioned recently, I have some familiarity with the characters and their inclinations via the cultural hivemind in the same way that I know about Bambi's mother and the man behind the curtain without having ever seen either Bambi or The Wizard of Oz. And of course, I have now also read an adaptation of A Study in Scarlet.

So while I'm starting to get a better handle on Holmes' moods and methods, prior caveats remain in that I cannot judge the faithfulness of the adaptation but can only judge the story as it appears to me in the Edginton/Culbard work. Any issues I take with the story will be issues that may or may not be a reflection of the source itself.

While Edginton and Culbard's A Study in Scarlet chronicles the first of Conan Doyle's Holmes stories, the pair adapted Baskervilles first (probably to help generate interest in a series I hope will continue for some time). In the backmatter, Culbard shares some of his original sketches for how he planned to render Dear Elementary Watson.* It's interesting to compare Edginton and Culbard's two adaptations. While Baskervilles is a fine book, one can sense certain refinements between it and Scarlet. The story flows better in Scarlet, but as I mentioned, I'm not in any position to judge whether that responsibility belongs to Edginton or Conan Doyle himself.

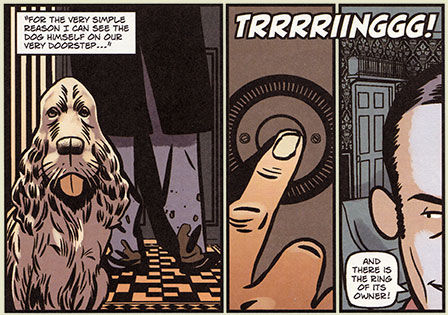

Regardless, even in keeping our focus on Culbard's work, we can note one singular improvement: less reliance upon technical gimmickry. In Baskervilles, Culbard experiments with Photoshop techniques to show skewed character reflections and these always look out of place. Later in the book, when rendering the moorish landscapes, he relies upon what I have to imagine are shopped photographs of the moors themselves. Each time, these additions look strikingly out of place, at odds with the wonderfully consistent style that Culbard brings to the rest of his work. Scarlet betrays none of these weaknesses so far as I remember and even though Culbard had the opportunity to experiment similarly in depictions of the American frontier, he thankfully restrained himself. I am always cheered to see an artist evolve through his work. (I am looking forward to seeing what Culbard does with The Sign of the Four, their next Holmes adaptation.)

As a detective story, I'm not sure exactly why it became such a popular event in Holmes' life. Perhaps readers of the era were unduly enamoured with the Scooby-Doo-style crossover of science vs. the supernatural. After all, if it worked for X-Files... Honestly, despite the presence of several cheats in the former tale, I really did prefer A Study in Scarlet. The present tale is built upon an overwhelming implausibility, namely that the villain would pursue the inheritor of the Baskerville fortune from his first step in London rather than simply wait for the man to walk, unsuspecting, into his trap. As the story wraps up, I found myself baffled as to why any would-be murderer smart enough to outstrip Homes in the early game would forfeit himself in such amateur ways.

On the other hand, I am kind of a sucker for glowing dogs.

Apart from my negative feeling toward the story's plotting and my (mostly) positive outlook on Culbard's art, there are two other points worth noting. For the one, the creative team again (for the first time!) does a marvelous job with Holmes' character. He is exactly as distant and arrogant and wry as I imagine he is meant to be. He is conveyed perfectly. For the other, Edginton and Culbard take an early opportunity to present Holmes as a genius whose inductive process is incredible though far from foolproof. In the earliest episode from the book, Holmes and Watson take on the task of identifying the owner of a walking stick based on nothing save the stick itself. Holmes is patronizingly charitable toward Watson's own attempt before revealing the whole truth of the matter. Which is then proven to be only partially correct by facts far more brute than his meager inductions. It is a humbling moment and Edginton and Culbard capture it flawlessly.

If The Hound of the Baskervilles was the creative team's first attempt and A Study in Scarlet their second, I am well onboard to see what they do with their third and can only hope their improvements carry on in a similar vector.

Note:

*Myth busted: Holmes said, "Elementary, my dear Watson," as often as Rick Blaine said "Play it again, Sam." Which was zero times.

Good Ok Bad features reviews of comics, graphic novels, manga, et cetera using a rare and auspicious three-star rating system. Point systems are notoriously fiddly, so here it's been pared down to three simple possibilities:

3 Stars = Good

2 Stars = Ok

1 Star = Bad

I am Seth T. Hahne and these are my reviews.

Browse Reviews By

Other Features

- Best Books of the Year:

- Top 50 of 2024

- Top 50 of 2023

- Top 100 of 2020-22

- Top 75 of 2019

- Top 50 of 2018

- Top 75 of 2017

- Top 75 of 2016

- Top 75 of 2015

- Top 75 of 2014

- Top 35 of 2013

- Top 25 of 2012

- Top 10 of 2011

- Popular Sections:

- All-Time Top 500

- All the Boardgames I've Played

- All the Anime Series I've Seen

- All the Animated Films I've Seen

- Top 75 by Female Creators

- Kids Recommendations

- What I Read: A Reading Log

- Other Features:

- Bookclub Study Guides