Hildafolk

One of the things missing from too much of our narrative experiences is a sense of whimsy. It's not so much that everything should be whimsical, but more that it seems the vast majority of respected works are serious-minded, somber affairs. Much of what are considered to be the best examples of the storytelling mediums are works that challenge the reader's sense of the world or delve into the not-so-sunny depths of the human condition. As readers of Great Literature, we've become suspicious of happy endings. We've come up against this great wall of human woe. And because it is valuable to consider the suffering that pours from its gates, we may have focused our attentions too narrowly in our search for literary worth and merit.

Whimsy doesn't come off so well in the critical eye when compared to the towering works of the literary canon. As wonderful as some of us know The House on Pooh Corner to be, it's hard to compare Milne with the likes of Kafka, Proust, Hemmingway, Joyce, and Conrad. Serious works just feel more literary, more artistically viable. Whimsy too is often mistaken for escapism and escapism (justly or not) has been targeted as the opponent of worthwhile artistic achievement. And if escapist narrative, by its nature, ignores with braggadocio the primary concerns of the Great Writers, then certainly books suffused with the whimsical must also be suspect.

But if we're willing at all to investigate these matters, we'll find that this is just not a helpful way to look at things. Especially as game studies begin to propagate, we're finding more and more that play is not just fun and not just good, but important. All of a life is worthy of consideration for those of attentive eye. The human condition is fraught with every manner of depravity but it is also marked by a resilience of pleasures. And really, as much as our literary examples of the whimsical betray a yen for the fantastic, so too do our more morose books — those books that detail the collapse of families due to lies and betrayals or the existential crises of characters burdened by self-inflicted woes. The novel is, in all cases, the bastion of fantasy. Story is, in its nature, a carefully composed unreality. And to miss that fact is to miss out on the value of even whimsy. And to miss out on whimsy would be to miss out on Luke Pearson's Hildafolk. And to miss out on Hildafolk would be a damned shame.

I picked up Hildafolk knowing that I'd love its art and design. I saw a press release for Hilda and the Midnight Giant (slated for release in May 2012) and was wowed by photographs of the book's interior art. Knowing that I'd want to get my hands on The Midnight Giant, I thought I'd better acquaint myself with whatever Hilda-mythos already existed, so I picked up Pearson's earlier work, the slim, elegant Hildafolk. Also known as Whimsy Central.

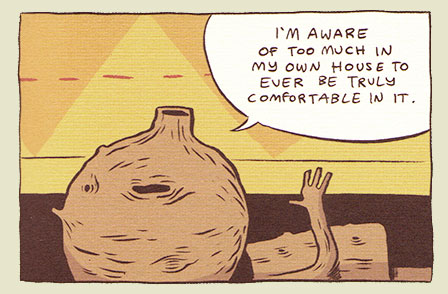

Hildafolk presents a terse tale of the precocious, blue-haired child, Hilda — and essentially just follows her around for a couple of days as she plays and explores and draws. Hilda lives in a mountainous hills-are-alive-with kind of setting and, as she is a child, has few responsibilities beyond staying out of Deep Trouble. Her current interests include reading about the different varieties of local trolls and scribbling in her sketchbook. Her companion is a blue-coated fox with adorable little antlers and her house is visited frequently and to her annoyance by a small man made of wood.

It happens.

It happens.

All of that is well and good, but the great joy in Hildafolk lies in its visual expression of the girl's life. Pearson's art is playful and perfectly rendered and evokes the kind of easy familiarity one finds in Carl Barks' Donald Duck or Jeff Smith's Bone. Pearson's palette is striking — perhaps one of the best I've seen in comics — and he uses the book's sense of colour to suffuse the reader in the book's unique mood. While Pearson generally maintains traditional paneling, some of my favourite of Hildafolk's pages were departures that utilized elements of the hilly topography to present a picture of how Hilda is spending her afternoon.

Hildafolk's story, while slight, exhibits a sense of humour that keeps even the book's darker moments from infringing too deeply on its sense of place. Actually, if I have one real complaint about Hildafolk, it's in regard to the book's brevity. It's not so much that Pearson didn't finish the story he was telling but more that I simply want a 400-page tome of Hilda. At forty-four pages Hilda and the Midnight Giant, when it comes, won't scratch that itch either. But I'm patient. If I live to life-expectancy, Pearson's got another forty years to satisfy me. For something this enjoyable, I'll wait.

Good Ok Bad features reviews of comics, graphic novels, manga, et cetera using a rare and auspicious three-star rating system. Point systems are notoriously fiddly, so here it's been pared down to three simple possibilities:

3 Stars = Good

2 Stars = Ok

1 Star = Bad

I am Seth T. Hahne and these are my reviews.

Browse Reviews By

Other Features

- Best Books of the Year:

- Top 50 of 2024

- Top 50 of 2023

- Top 100 of 2020-22

- Top 75 of 2019

- Top 50 of 2018

- Top 75 of 2017

- Top 75 of 2016

- Top 75 of 2015

- Top 75 of 2014

- Top 35 of 2013

- Top 25 of 2012

- Top 10 of 2011

- Popular Sections:

- All-Time Top 500

- All the Boardgames I've Played

- All the Anime Series I've Seen

- All the Animated Films I've Seen

- Top 75 by Female Creators

- Kids Recommendations

- What I Read: A Reading Log

- Other Features:

- Bookclub Study Guides