Habibi

A couple weeks ago, I read and reviewed Chester Brown's Paying For It, a book singularly concerned with separating love from sex. Brown forwards the idea that fewer problems arise if we segregate sex as completely as we can from the relational sphere. He does this to such an extent that he proposes that sex is a pleasure best paid for and made entirely transactional. It's not spoiling anything to say that Brown, as he represents himself in the book, is more wholly concerned with sex than he is with relationship. Despite the author's protestations, readers will almost certainly feel some sorrow for him as he shows himself unable to enjoy the manifold blessings of romantic relationships. We watch his philosophy play itself out and wonder: is it enough?

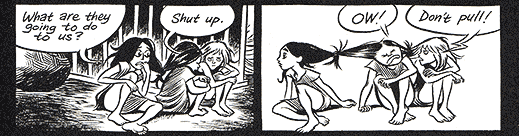

Craig Thompson's latest work, Habibi, may function well as a companion piece to Paying For It, only emphasizing the inverse of Brown's work: love that excludes sex. Thompson balances several themes throughout Habibi's unfolded history of two runaway slaves, but perhaps chief among these is an exploration of love, of true love—and how it can exist, flourish, and grow even in the absence of sexual fulfillment. Chester Brown focused on his women as pure objects, as receptacles for his sexuality to the exclusion of their ability to exist as full-orbed human persons with dreams, hopes, loves, or even (for the most part) personalities; Thompson, on the other hand, uses the objectification of his characters to craft them into noble persons deserving of dignity, of hope, of love.

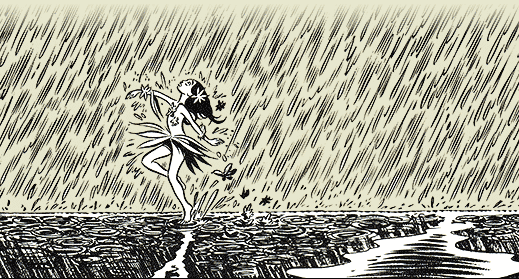

Thompson walks a narratively perilous path, pushing envelopes with his characters that draw out the terror of the human spirit and balancing against the redeeming power of a full-bodied and depth-defying love. The story he crafts is dangerous because as his characters participate in choices that may seem abominable—and in some sense they are abominable choices, made so by their sheer necessity—Thompson risks the reader losing interest in their plight. Still, the compassionate reader won't be able to help investing themselves into their two stories, which are really just one story.

In Habibi, Thompson introduces us to his heroine, Dodola, as she is sold into marriage to a scribe who will teach her to read, to understand the power of stories. Dodola is nine and Thompson does not spare us the aftermath of her wedding night. What's worse is that the anguish of such a scene, such an experience, is small in comparison to the fate Dodola and her adopted son Zam will live out. Thompson makes a cruel god for his world and creations; yet it is in his cruelty that we see the beauty of Dodola and Zam spill out in Habibi's nearly seven hundred pages.

Habibi is a major work in comics literature and Thompson's first since the nearly-six-hundred-page Blankets. Comparisons will be obvious. Both works traffic deeply in religious language and colour their texts in displays of sacred ferocity. Both explore the boundaries and need for love and human contact. Both play with non-linearity in storytelling, skipping back and forth and only revealing the past in time to illuminate the future. These two creations are very much the work of the same author and it's a joy to see his voice maturing.

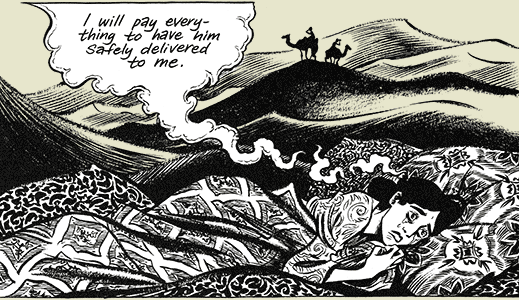

Still, for those hoping for another Blankets, Thompson has something very much different in store. In both tone and scope, Habibi is an entirely more ambitious work. We see Thompson redressing things that were focal points in Blankets. In the former book, Raina is depicted in such sacred light by Thompson that she becomes the ultimate example of female sexual objectification—all with the best intentions of course, but when young Craig deifies her, he makes her into little better than a graven image. In Habibi, however, when Dodola is depicted nude (which is often), she is wholly human. This is a triumph of Thompson's technique, for in the midst of the narrative she is being wholly objectified, yet these instances serve only to drive home her humanity. For the majority of those within Habibi's narrative landscape, Dodola exists much as Chester Brown's ideal woman—she is merely a receptacle for their sexual advances. Thompson, however, prevents the reader from seeing her in this way by refusing to give her the visual lyricism he bestowed upon Raina. Both are sacred and both are holy, but the one is made so by her sexuality while the other is made so by her personhood. It's a difficult line to draw and that Thompson illustrates it so well ably demonstrates why he is one of the leading auteurs in the medium.

Even odds that Thompson actually tried this out at some point in his life.

Even odds that Thompson actually tried this out at some point in his life.

Habibi is a book marked by rape, slavery, castration, forced marriages, the murder of children, harems, and love. While in its murk and depths, it may not seem possible that the last of these—love—should so completely over-power all else, this is the case. Love is not always victorious, but it is always glorious. The love of these two for each other is simultaneously heart-rending and heart-warming. For this reason, when Habibi asks of love without sex, Is it enough? the answer, though quiet in the face of the world's roar, is defiant: Yes, it is.

Note

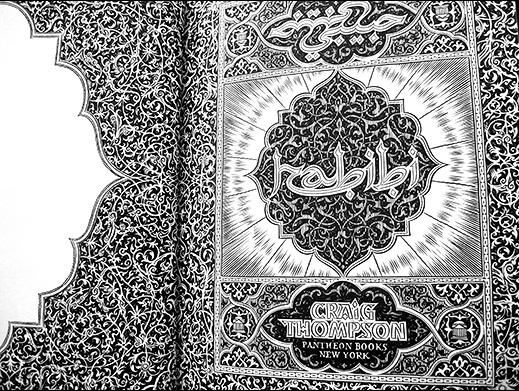

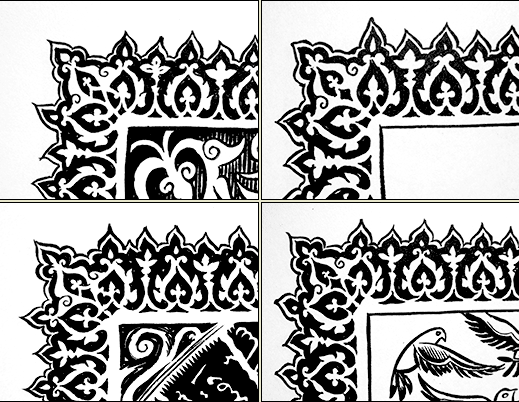

One word about the art: it's manifestly evident why this book took Thompson six years to create. Beyond the research necessary to develop such a well-rounded story that borrows so heavily from the Qur'an, Habibi's art is a wonder. The intricacy with which Thompson approaches his pages staggers the imagination—especially when one recalls the stress-injury pain in his hand that he related in Carnet de Voyage. So many of the pages of Habibi feature delicate ornamentation pulled from Islamic culture, ornament that would take hours to complete. Here's an example:

These are corners from four different instances, showing the kind of decoration that Thompson wrapped around entire pages. At first I presumed that he drew this just the once and reproduced the designwork for subsequent pages. This photo though shows that each page's work was distinct. That Thompson took the care to patiently (or impatiently, it hardly matters) draw out these magnificent designs helps flesh out just how much effort was poured into this production. The six years shows and Thompson outdoes anything I'd seen from him previously.

Good Ok Bad features reviews of comics, graphic novels, manga, et cetera using a rare and auspicious three-star rating system. Point systems are notoriously fiddly, so here it's been pared down to three simple possibilities:

3 Stars = Good

2 Stars = Ok

1 Star = Bad

I am Seth T. Hahne and these are my reviews.

Browse Reviews By

Other Features

- Best Books of the Year:

- Top 50 of 2024

- Top 50 of 2023

- Top 100 of 2020-22

- Top 75 of 2019

- Top 50 of 2018

- Top 75 of 2017

- Top 75 of 2016

- Top 75 of 2015

- Top 75 of 2014

- Top 35 of 2013

- Top 25 of 2012

- Top 10 of 2011

- Popular Sections:

- All-Time Top 500

- All the Boardgames I've Played

- All the Anime Series I've Seen

- All the Animated Films I've Seen

- Top 75 by Female Creators

- Kids Recommendations

- What I Read: A Reading Log

- Other Features:

- Bookclub Study Guides