The Grand Inquisitor

I've always enjoyed the idea of unfaithful adaptations. In truth, I largely* prefer an adaptation to stray dramatically from its source. The more wildly and inventively a work reworks the fountain of its inspiration, the more respect I'm likely to have for it. A film that takes Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials, sets it in 1920s' Chicago, and recasts it as a polemic in favour of Shintoism would be a phenomenal experience. Because, really, the only point in straight adaptation is to glad-hand the adapted material's most ardent fans with a slavish reinterpretation of the object of their infatuation.

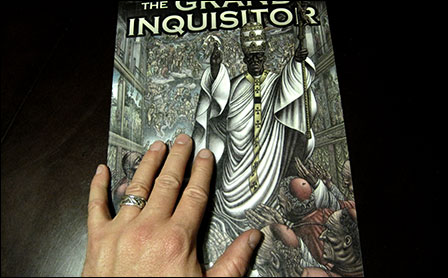

So repurposing Dostoevsky's "The Grand Inquisitor" (a piece from The Brothers Karamazov) to read as a Third Millennium exploration of the battle between conservatives and progresssives for the heart of the Papacy could have been incredible. As The Grand Inquisitor's two creators are entirely unknown to me and the book hails from a small Roman Catholic press, I couldn't have too many expectations to lay upon the work. Still, just looking at the book's large** cover portraying a black pope in all his apocalyptic finery excited me a bit at the possibilities—possibilities that due to both art and writing only ever remained a distant, unapproachable goal.

Author John Zmirak takes a unique tack, pressing all the text found in The Grand Inquisitor into the constraints of poetic verse. Readers will differ on how successful he is here, but allow me to betray a personal preference for a moment. I've rarely found a time when prose wasn't superior to verse in expressing meaning. Philistine I may be, but my predisposition to think lowly of poetry definitely colours my experience of Zmirak's writing here. The narrative is poetry, the dialogue is poetry, and the news casts itself in poetry. It's largely blank verse (and I imagine would be read in some sort of slam performance), though the newscaster reads in rhyming couplets.

The problem is that Zmirak has an interesting story at stake, but he obfuscates his purpose, forcing the reader to slog through what doesn't even look to be well-penned verse. On second thought, that may be my aversion talking. Here's a sample (that you might judge for yourselves):

He looks like the nigger on the black boot polish can!

"Sambo brand," I remember. Used by Mussolini.

And what if I let him go? Or better,

embraced this extravagantly gallant

negro, and led him back to the Conclave?

The thought warms an old heart like a ray of

sunshine on the Appenine ice that packs

an organ traveling for a transplant.

One enjoys the warmth. But should one feed it

with a life's work? Let all that be consumed

by sentiment, a weakness of the nerves?

Sir, here's your chance to prove that you should leave

this room unharmed and ride to the Conclave.

I'll call the taxi.

By what authority proceed, what right?

Tonight, the right of conquest will suffice.

What is your post in the Conclave?

I am its Holy Ghost.

It is a role I've exercised some fifty silent years.

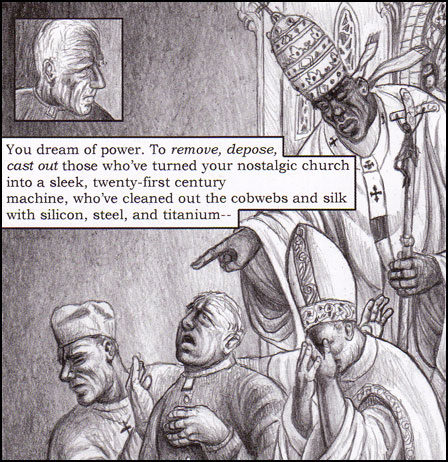

Read that as you like but my take away is that Zmirak ruins his work by smothering it in device, by miring it in unlyrical artificiality—which is a shame, really. The story, when one comes to recognize it, is fascinating enough. The old pope has gone to ashes and the Conclave is trapped in deliberations, hunting for the next to wear the Ring and Hat. The progressives want a papacy dedicated to taking the new world on by that world's terms—at the low cost of dumping outmoded doctrine, if that's what it takes to be relevant. The conservatives, of course, wish to retain the majesty of two millennia of history's weight, of councils and bulls. Into this cacophony steps a Sudanese man, called from Africa to claim the Vatican for those who would throw the heterodox out on ears, a black man to woo the world's cameras and sooth the sting of doctrinal fidelity. He is kept from the conclave, however, by an old liberal man of cloth and designs, kept in a madhouse and questioned between threats of Thorazine. The Grand Inquisitor is laid out as conversational gladiatorialism, a battle between Old Nick's advocate and the church of the narrow road. This back-and-forth between the white liberal and the black arch-conservative plays out like Christ in the wilderness being tempted by the prince of the Fallen. It all could have been so notable had not Zmirak felt the need to torpedo his idea by forcing upon it the gimmick of poetry.

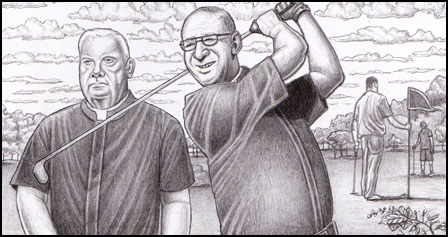

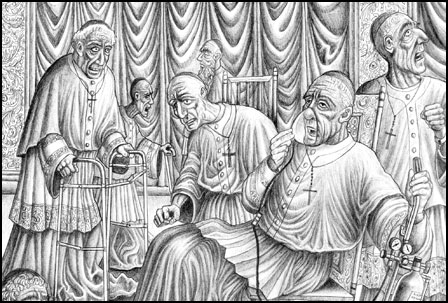

Beyond that, the art is a struggle as well. It's hard to tell whether Carla Millar is an honestly talented illustrator who's consciously wielding a stylistic tic or maybe she's actually got the chops of a talented ninth grader who's never had any official instruction as to anatomy or the formation of drawn persons. The Grand Inquisitor's pages, for all their complexity, resemble too much the mural on the wall of your local pizza place that had been painted by the owner's nephew who's had a couple semesters of art in high school. Drawn characters seem to have that whimsical variety of facial muscles that were popularized in the early '90s profusion of Image artists—despite having no earthly analogue.

I'll be honest in saying that I struggled to get through this book. Its provenance in Dostoevsky was my motivation for pursuing the thread to its happily ambiguous conclusion. There were things that I liked—things that crept out of the creative swamp as I pushed my way through. By the end, I realized that this was a story that I was excited about—in principle. If Zmirak would have scripted his story differently, the work could have been salvaged. One might have even been able to overlook the art or the fact that all dialogue is presented in Times New Roman*** had only Zmirak remedied his presentation of dialogue. As it is, I can't say I look forward to his next work. Maybe he'll surprise me (not that my approval is his goal, by any means). I might even light a candle to whomever the patron saint of good comics is.****

Notes

* There are of course exceptions. Fight Club is a generally faithful adaptation of Fight Club but puts all its bang into visual and editing tricks unique to its cinematic expression, making it a perhaps superior product to its source. Snow Falling on Cedars almost slavishly adapts its sources but does such a good job that it becomes a far more powerful experience than the text from which it derives.

** By large I mean huge. And by huge I mean very big. Look at this thing. It's the size of twelve cows.

*** It might not actually be Times New Roman. It might be Garamond or any number of other serifed fonts that look acceptable in prose novels but atrocious in comics.

**** Just saying this proves I really have no idea how the Roman Catholic interaction with the saints (patronizing or otherwise) plays itself out. From movies, I understand there are saints and that there are candles. And I think that they sometimes go together. Or seem to in movies.

Good Ok Bad features reviews of comics, graphic novels, manga, et cetera using a rare and auspicious three-star rating system. Point systems are notoriously fiddly, so here it's been pared down to three simple possibilities:

3 Stars = Good

2 Stars = Ok

1 Star = Bad

I am Seth T. Hahne and these are my reviews.

Browse Reviews By

Other Features

- Best Books of the Year:

- Top 50 of 2024

- Top 50 of 2023

- Top 100 of 2020-22

- Top 75 of 2019

- Top 50 of 2018

- Top 75 of 2017

- Top 75 of 2016

- Top 75 of 2015

- Top 75 of 2014

- Top 35 of 2013

- Top 25 of 2012

- Top 10 of 2011

- Popular Sections:

- All-Time Top 500

- All the Boardgames I've Played

- All the Anime Series I've Seen

- All the Animated Films I've Seen

- Top 75 by Female Creators

- Kids Recommendations

- What I Read: A Reading Log

- Other Features:

- Bookclub Study Guides