A Girl on the Shore

"Both elbows on the table, I covered my face with my palms. Inside the darkness, I saw rain falling on the sea. Rain softly falling on a vast sea, with no one there to see it. The rain strikes the surface of the sea, yet even the fish don't know it's raining. Until someone came and lightly rested a hand on my shoulder, my thoughts were of the sea" (from South of the Border, West of the Sun).

While better known for his epic, bizarre excursions into real-but-magical worlds of talking animals, dreams that infect the day, and empty-shelled men and women who might never be whole again, it's often in Haruki Murakami's quieter works that I find his best expression. For a long time The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle was my favourite of his bibliography. It may still be—that's a hard thing to decide. But after reading about ten of his works, I came across South of the Border, West of the Sun, and I was floored. I had understandably grown accustomed to his writing, his themes, his tics. I was still appreciative of his work but no longer excited. Everything felt familiar.

But with South of the Border, I felt as if I were reading the best distillation of the map he wanted to leave us to find entrance to his world. It's a terse work. 213 pages. Nothing like the 600+ page works that mark the usually noted high points of his collection (Wind-Up Bird, Kafka on the Shore, and 1Q84). South of the Border is mundane by Murakami's standard, a love story and a story of love sustained in absence. It's a story with pockets of frank eroticism—in place much less to titillate than to unveil character and purpose. And then, at the end of the day, South of the Border, West of the Sun's love story is not actually even the point, and instead we find we've been present for a coming of age story that is stretched across four decades. Through an evocative coda, life-bringing rain cleanses in the midst of a psychological turmoil and peace settles through the mundane act of simple human contact. A winding, fraught journey of fumbling and longing ends in a simple realization, unstated and understated.

When I read the American press for Inio Asano's A Girl on the Shore, I was thrilled to find that the book was apparently inspired directly by Asano's experience with Murakami's Kafka on the Shore. That is an invocation brimming with mystery, for Kafka is almost certainly the strangest of Murakami's works. It was the first Murakami I ever read and spurred my reader's imagination in new ways—I had never encountered anything of the like. However, I've poked around and haven't been able to find any corroboration for the cited inspiration. Googling in English only returns references back to the original press release. A friend who lived in Japan until she was 25 or so searched that corner of the internet for me and after forty-five minutes (an admittedly brief dive into the web) could only uncover piles of people discussing how very like a Murakami novel Asano's book is. Still, whether A Girl On The Shore is actually inspired by Murakami or not, it's certainly very plausible. Interestingly, the book only holds a glancing likeness to Kafka on the Shore and seems much closer paired with South of the Border, West of the Sun.

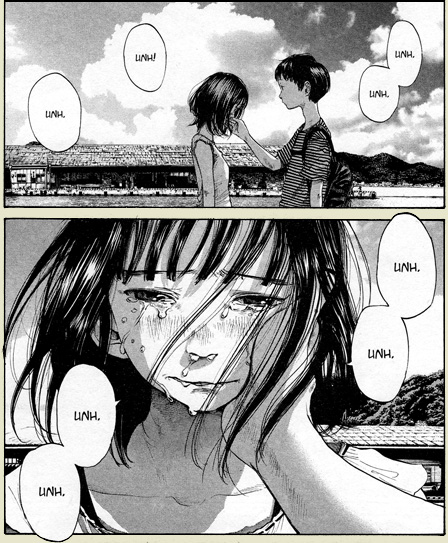

A Girl on the Shore opens with an awkward post-coital walk along the shore of a somnambulant little town in which two ninth graders discuss whether to forge a romantic relationship out of what the girl viewed as a virginity-losing one-afternoon stand. The girl, Sato, wanted a bit of sex in order to feel something, to rage against the way another boy (the one she pines for) abuses her and is dismissive to her. She instinctively reaches out for a measure of control and convinces Isobe, who's long been attracted to her, to put a little sugar in her bowl (to euphemistically borrow from Nina Simone). She knows he will, and so she takes advantage of that attraction. She's still unfilled, but she's awakened a curiosity and a need.

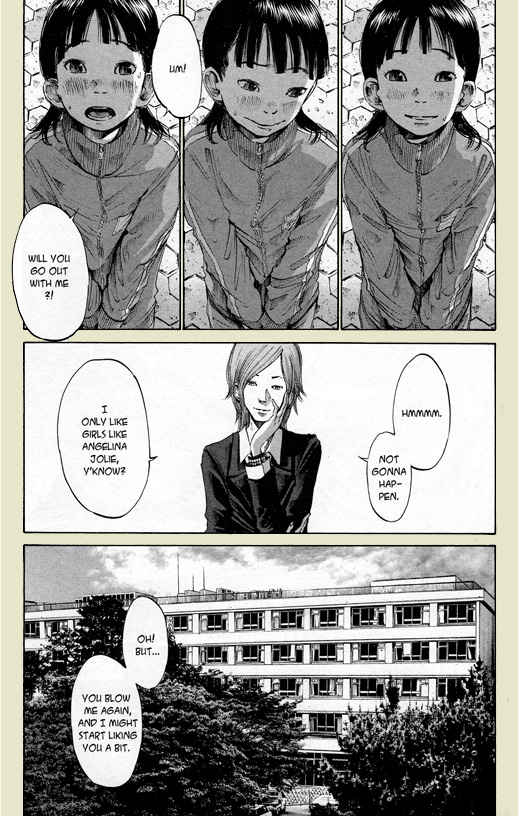

Misaki is a fantastic choice to have a crush on

Misaki is a fantastic choice to have a crush on

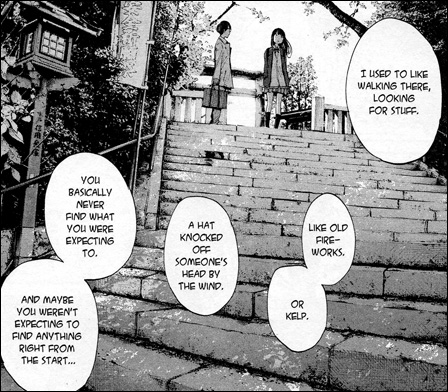

All of this happens before page 1, and Asano allows us to join them in media res as Isobe asks Sato if she wants to be his girlfriend. But she doesn't think of him like that and cannot be involved with him romantically while she is hoping against hope that Misaki, the cad of her dreams, will finally return her affections. It takes a couple days, but Isobe and Sato iron out a kind of rhythm in which they engage in frequent, escalating, no-strings-attached sexual exploration. The trick of course, as every story ever has taught us, is that we can't always see the strings that guide us, bind us, and draw us. Especially not when our eyes are glued tight in orgasmic ecstasy.

Things play out as they will as the kids head toward graduation and on to high school,11Remember that what is the first year of high school in the US is last year of junior high in Japan. and everyone discovers that the things they believed so deeply and strongly were most likely only their eager imaginations, fueling and burning in engines of youthful madness and indiscretion. There's a certain profane beauty and chaos to it all. In some ways it reflects the common boy-girl experience and in other ways is horrifyingly unique. There is nothing healthy being explored, but the whole experiment was never about health. It was about overcoming alienation and extorting life into healing without bandaids or antiseptic.

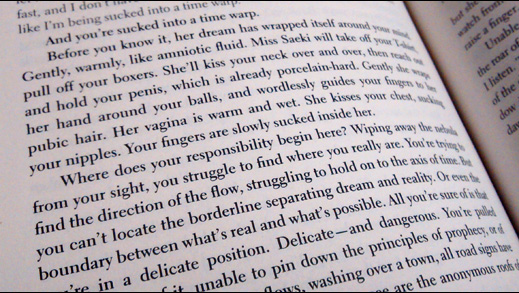

One of the marks of Murakami's fiction is his very dry, almost lifeless descriptions of sex. Those unfamiliar with his style and its use might mistake his sex scenes for clumsy because if there is one thing they are not, it's sexy. They are descriptive, spare, and get the point of the encounter across without making the scene lurid. Here's a sample from Kafka on the Shore.

from Murakami's kafka on the shore

from Murakami's kafka on the shore

The point of Murakami's sex scenes is either a) to convey human proximity and establish the intricacy of the social realm through non-expository means; or b) to investigate an abstract through the concrete act of the sexual encounter. I'd say that sex in Murakami is sometimes probably just sex, but I can't actually think of any candidates from his books where that would be the case.

In A Girl on the Shore, Asano's fashioned a curious work in that it conveys with a certain coy frankness a relationship that many of us are uncomfortable seeing depicted. Asano skirts around Japanese censor restrictions by drawing Isobe's penis as an outline admitting no detail and by indicating penetration through artful use of negative space. Despite his restrictions, one feels the cartoonist's lens has not blushed away from the activities depicted at all. And yet, because these scenes are not in place to titillate22Though they may very well enflame the prurient interest quite as well as had that been their sole purpose., the scenes are not gratuitous. Like Murakami, Asano has installed these episodes to an end—in his case, to investigate an abstract through the means of establishing character proximity.

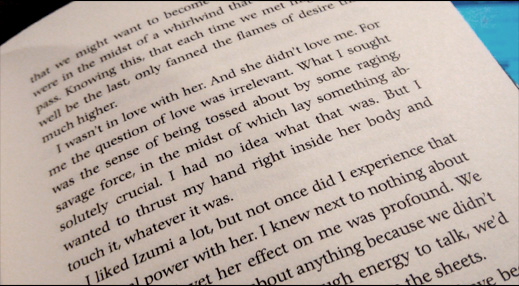

Sato and Isobe begin with plain vanilla sexual exploration. Isobe's clearly done this before, but apart from a blow job she gave to Misaki (only given in hopes that he would ask her to be his girlfriend), Sato begins the story as a virgin. As their encounters increase in frequency, there begins a sort of staleness. At one point Isobe has his head installed under Sato's skirt to stimulate her orally, but Sato just browses photos on a camera, bored by the whole endeavor. Still, while motivated in entirely different ways, they are fueled by a relentless hunger for sexual expression apart from love (though in fairness Isobe begins by hoping their sex will lead to something more). They, in this way reflect an episode from South of the Border, West of the Sun, in which the narrator Hajime describes his relentless sexual relationship with his girlfriend's cousin:

from Murakami's South of the border, west of the sun

from Murakami's South of the border, west of the sun

That passion is essential to the story being told and were this a more moralistic fable, we'd see it devour them. By the end, their sex gets more and more exploratory and almost entirely compulsory, but if there's going to be a destruction of what they have, it's not going to be the sex that does them in. Rather, the sex is merely symptomatic of larger struggles, of grander more encompassing needs. Needs that are at odds with each other's.

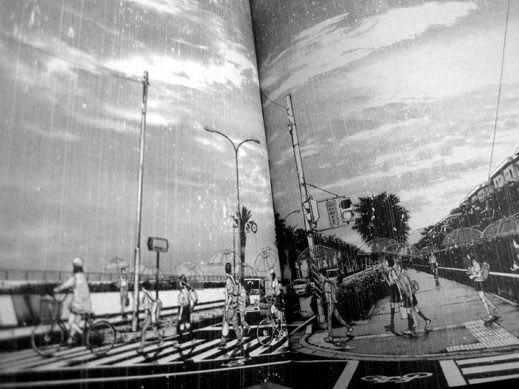

Asano's illustrations are better than ever and surpass anything yet seen in his US-adapted works (What a Wonderful World, Solanin, and Nijigahara Holographic). His character work is detailed and lively and he conveys expression wonderfully. I'm not sure the exact technique used to derive his backgrounds (they appear to be some sort of high-contrast scan of reference photos blended with honest illustration),33UPDATE: Since posting, German reader Karsten has pointed me to this wonderful episode of Naoki Urusawa's mangaka interview series, featuring Asano and his illustration technique. but whatever the method, Asano composes some lovely scenes and really only on the final page of the book does a character feel pasted in atop a stage set.

I also feel his writing's stronger here than the rest of his revealed oeuvre, but that may be because the last of his works I read was Nijigahara Holographic, which was kind of a shambles. (I barely remember Solanin at all, actually, as it's been about seven or eight years since I last read it.) In any case, the dialogue worked fine and the evolution of events and characters built well toward the book's conclusion.

There is—for me—always a fairly strong element of disbelief suspension that necessarily goes along with most stories of sexual flamboyance. Ignoring for a minute the fact that when I was fifteen, I was struggling to tell the girl I liked that I liked her. Nevermind that I wouldn't have ever considered shoving my hand down her pants to finger her. Forget all that. Certainly there are kids whose self-expression along these lines appears far more confident than anything I could have mustered. But what really baffles me is the sheer endurance and prowess of these characters. Teenaged Garcia Madero from Roberto Bolaño's Savage Detectives has what seems like hours of wild, mind-expanding sex with an architect's poet-daughter one night. He climaxes and immediately goes in for seconds. Thirds. Fourths. It's mythical and legendary and epic and I can't begin to imagine. At that age, I likely would have blown my top in minutes and been done in for hours. Similar to poet Garcia Madero, fifteen-year-old Isobe is a juggernaught in the sack. He'll masturbate, then have vigourous sex, then get a blow job. All in the space of a couple lazy hours. Maybe that's entirely possible and even normal and I'm just revealing some previously unknown inadequacy of my own, but when stuff like that happens it seems so far from plausible that I can't figure out how writers keep writing these scenes.

Also, I get phantom soreness just thinking about it. 'Cuz, man, that would honestly get pretty raw.

As with an earlier work, Solanin, Asano here bookends his story with some thematic text. After a brief prologue, he presents a black page with seven short sentences that will remain suitably vague until the book's conclusion, where they are repeated in dialogue that will lead directly into coda and resolution, which carries similar function to that bit of South of the Border that I quoted at the beginning of this review.

While one could be forgiven for thinking A Girl on the Shore is about a very young man and a very young woman having sex, a more legitimate back-of-book description would involve some attempt to express the characters' efforts to find what they're looking for, even while they have no real idea what they're looking for. Love. Solace. A good bone. Meaning. Purpose. Catharsis. Control. Freedom. A reason not to float away into nothingness. A Girl on the Shore is predicated on the idea of finding things unsought. In their evolution from children to adults, Sato and Isobe will see their heavens rolled back as a scroll and epiphanies will rain down on them in the most mundane and everyday sorts of ways. But that happens to us all. The only remaining question then is what these two will do with their own unique revelations.

Good Ok Bad features reviews of comics, graphic novels, manga, et cetera using a rare and auspicious three-star rating system. Point systems are notoriously fiddly, so here it's been pared down to three simple possibilities:

3 Stars = Good

2 Stars = Ok

1 Star = Bad

I am Seth T. Hahne and these are my reviews.

Browse Reviews By

Other Features

- Best Books of the Year:

- Top 50 of 2024

- Top 50 of 2023

- Top 100 of 2020-22

- Top 75 of 2019

- Top 50 of 2018

- Top 75 of 2017

- Top 75 of 2016

- Top 75 of 2015

- Top 75 of 2014

- Top 35 of 2013

- Top 25 of 2012

- Top 10 of 2011

- Popular Sections:

- All-Time Top 500

- All the Boardgames I've Played

- All the Anime Series I've Seen

- All the Animated Films I've Seen

- Top 75 by Female Creators

- Kids Recommendations

- What I Read: A Reading Log

- Other Features:

- Bookclub Study Guides