Genius

Created by: Steven T. Seagle and Teddy Kristiansen

Published by: PUBLISHER

ISBN: 1596432632 Amazon

Pages: 128

Finally, a book that understands what it's like.

I'm kidding. Mostly. Probably. The fact is a lot of us can probably relate in at least some manner to Ted Halker, his sense of alienation, and his frustrating struggle to live up to his potential—especially while others may seem to live up to theirs almost effortlessly. I may not be a genius (or maybe I am!), but I've lived Ted's trials with exactitude. If you don't count the particulars of his plotline.

Truth.

Truth.

The question of potential and potentialities looms over Seagle and Kristiansen's latest collaboration, Genius. The book's eponymous genius, Ted, is haunted by what he could be if only he would be what he could be. He's likewise stalked by the undeterrable weaving of fate and the question of how his actions in the present might deterministically prompt the ultimate form of that tapestry.

It's a trim book and an easy read, but it tussles with concepts that lend their own formidable weight to the whole enterprise. The questions of ethics, will, determinism, responsibility, and sacrifice form the bedrock of (if not all then many) introductory philosophy courses—because, after all, these are the questions that plague our human existence. Their answers (and even more: the demurring to answer) have ranging effects in the personal, familial, and community spheres. Seagle and Kristiansen avoid specifics for the most part but do suggest an angle of descent for approaching broadly the ethics of circumstance. It's likely that the creative team's purpose was more to provoke the question in their readers than it was to propose a solution—and so far as this is their goal, I believe most will find their book a success. They leave plenty of room for discussion, neither making Ted a paragon nor a villain for his final solution. I imagine that every book club to discuss Genius will ask in some form or another the question, "What would you have done in Ted's place?" A kind of Sophie's choice gimme of a question that is nonetheless appropriate for all its cliched guise of introspection.11Cliched because what moderator on earth would avoid such an obvious line of group inquiry. Guise because what impossibly slim percentage of book club members discussing Genius are actually going to themselves be geniuses and therefore be able to calculate the complications of Ted's position?

Writing a story about a character who is a genius is probably the most difficult kind of story there is to write. Creating a believable character who is substantially different from the author is never easy and falls apart in any number of aspects that are just plainly beyond the writer's grasp. We see this all the time when a man is writing a female protagonist, when a white woman is writing a black woman, when a straight woman is writing a gay man, when an atheist is writing a believer, or vicey-versa. Writing someone who is not you is incredibly difficult to accomplish in a manner that could be mistaken for verisimilitude. But in each of these cases, a little bit of empathy can go a long way toward selling the illusion. The old trick of using one's imagination to walk a mile or kilometer or league in another's soles really can help bridge the gulf between author and character. The problem with writing a genius is that no amount of empathy or imagination can make your character smarter than that character's author. Because of this, it's rare to encounter a figure within the literary tradition who actually feels like the genius he or she is meant to be.

Still, whatever the case, floating Einstein will always be a genius.

Still, whatever the case, floating Einstein will always be a genius.

To ease the tension and help prompt the myth of intellectual brilliance, writers have a number of tricks at their disposal—gimmicks that can help sell the heroic smarts of their protagonists. A small list of a number of these:

- The character will tell you that they are a genius. Or at least passingly mention their IQ or how Mensa is beneath them.

- The character will give you simple-but-quirky explanations for everyday things as proof of their above average intellect.

- They will have a genius-person job.

- They will scribble equations on things. It doesn't matter whether the equations are legit or related to their field of study or accurate. All that matters is that the equations are scribbled—because without either familiarity with the equation being scribbled or what the variables represent, the reader will just have to take on faith that the complexity is relevant and accurate.

- Jargon, doesn't even have to be real. Quantum gyrations. Planck strings. Acoustic radiation. Perpentudinal ethnoplexies. (See also 97% of all sci-fi stories.)

- Name dropping of peers. Einstein. Schroedinger. Dirac. Quine. Russell.

There are other gimmicks, but these are common. And better, they're generally acceptable ways to aid in the reader's suspension of disbelief. And I'm not complaining, really. How much worse would it be for an ostensibly popular work to essay a completely believable and legitimately genius protagonist? Only the slimmest percentage of the readership would understand any of it.22One of the greatest praises of Ottaviani's Feynman is that he renders Richard Feynman's legitimate genius in a readable, easy-going way (thanks in part to Feynman's own work in rendering himself approachable). This becomes the more evident when Ottaviani unleashes an unexpurgated Feynman on the reader in the form of for-reals science in a concluding lecture, wherein Feynman endeavors to explain QED to an audience (and the reader). It's mostly impenetrable to the average reader, but because it's a short moment, it drives home Feynman's intellect and imagination in a way that gimmicks could never do.

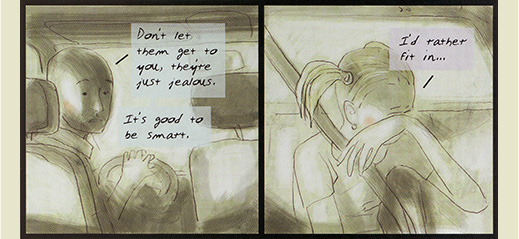

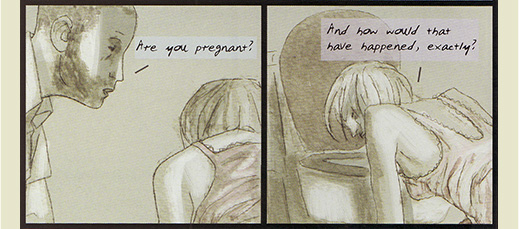

Smart guy being oblivious to female biology, however: that is a sure marker of genius.

Smart guy being oblivious to female biology, however: that is a sure marker of genius.

So when we discover that Seagle and Kristiansen rely on the standard bag of tricks, it's at first understandable if still a bit disappointing. (I really want to read about a genius and actually rationally believe he is a genius, but still enjoy reading about him. Chimeric, I know.) But after a few pages, we realize that it doesn't matter so much. We're not going to be asked to believe that Ted will solve impossible equations like Matt Damon in Good Will Hunting. We're not going to see Ted put into a situation where his genius will be put on display. We're not going to be asked to believe it when Ted contradicts scientific theory and changes the world for the next century. That's the stuff of biographies and isn't what the creative team has on its plate for Genius.

Instead, and amusingly (probably), Seagle and Kristiansen propose a very mundane problem—one sadly enough encountered by non-genius people every day. Ted's intellect allows him an improbable out, if he will take it, but otherwise this is really the tale of every one of us in some respect. Potential and potentialities. Ted's story is about the weighing of consequences and "being man enough"33I do not invoke Manliness because I carry any special affection for the concept but only because Ted's father-in-law values manliness and balls and real men et cetera. to take responsibility for the results of our judgments. It's about who we are and who we might become. It might be the story of a genius but it doesn't need to be. And while Seagle and Kristiansen involve Albert Einstein's ghost rather often and rather effectively, he's really only the crutch Ted needs to become what he might become. Scientist as catalyst.

This panel was harrowing to me. Been there, done that.

This panel was harrowing to me. Been there, done that.

So here's a funny thing about Seagle/Kristiansen books. I always want to read them until I pick them up. I read that a new collaboration is to be published and I get excited, remembering how much I enjoyed their last creation. Then I get the book, thumb through it, and decide that maybe I'll wait a while and read it when I'm in the mood. There's no real justification for it save for Kristiansen's palette. The artist uses downbeat colours that are dingied and desaturated. If a range of colours could be given a name, Kristiansen's would be named Eeyore. There is none of that cheery blossom of wonder that fills Miyazaki's works, none of that alternating between soft and bold that marks Glyn Dillon's latest. Even Frank Miller's Dark Knight, which often has a similar monotone of blues and greys, employs its hues to bursting dramatic effect.

So in a sense, I'm always predisposed to not enjoy these Seagle/Kristiansen ventures. Which is great because I always end up deeply appreciating their work and thinking that Kristiansen is probably the perfect artist to bring Seagle's stories to visual life. Despite my initial reluctance, I always discover myself pretty amazed at what Kristiansen can do, and while reading I never find myself feeling the visual tone unwieldy or too depressing. So you'd think I would learn. I probably won't (I'm not that kind of genius), but I really ought to.

Genius, for all its slim page count (126 pages!), is a lovely and thoughtful work. I'm hoping that by year's end, the book will be Number 15 in my best-of-the-year list—because that would mark 2013 a truly phenomenal year for comics. As it is, I don't doubt that Genius will land in my Top 5 (even as Kristiansen and Seagle's The Red Diary did for 2012). I'm enthusiastic for the book. Because it's Good. And even probably Very Good.

The One Thing I Hated

This is almost a triviality, but a triviality that was so pervasive that it constantly threatened my reading of the book. Genius uses a handful of typefaces rather than hand-lettering. No big deal, that. Almost everything these days uses custom fonting and you'll hear no complaint from me. If I were to put out a book, I'd probably do the same. The problem with Genius is not that it uses typefaces but with one of the typefaces used.

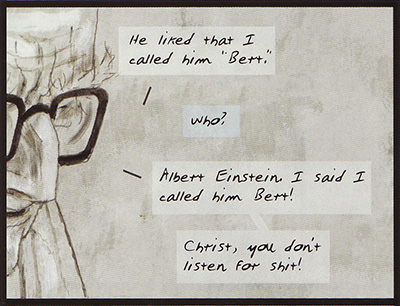

Particularly with respect to lowercase Ts and Rs. Here's the first panel I noticed the problem:

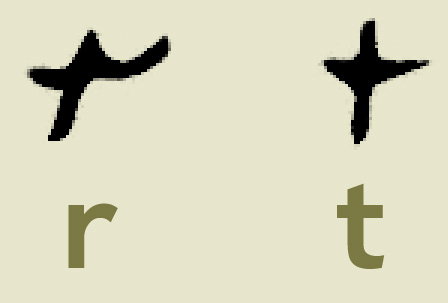

The Rs and Ts are so similar that I thought Ted's father-in-law was calling Albert Einstein Bett and referring to his real name as Albett. The guy's suffering a bit of dementia, so it's not impossible. But he's not calling Einstein "Bett." It's only the font that makes it look like that. Here's an up-close comparison of the two letters:

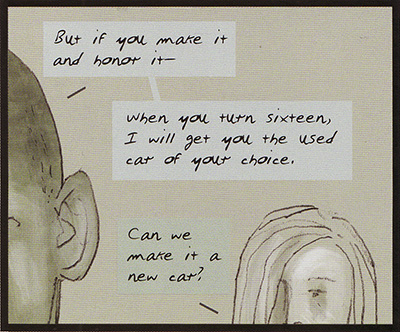

They're different, but not remarkably so. My wife stumbled on the lack of distinction earlier than me in this panel where Ted makes a deal with his son. She was baffled at why Ted would offer his son a used cat.

The idea of Ted offering his son a used cat

The idea of Ted offering his son a used cat

is actually way funnier than his actual offer.

Again, it's not a big deal, but I'm disappointed that the issue exists at all.

Good Ok Bad features reviews of comics, graphic novels, manga, et cetera using a rare and auspicious three-star rating system. Point systems are notoriously fiddly, so here it's been pared down to three simple possibilities:

3 Stars = Good

2 Stars = Ok

1 Star = Bad

I am Seth T. Hahne and these are my reviews.

Browse Reviews By

Other Features

- Best Books of the Year:

- Top 50 of 2024

- Top 50 of 2023

- Top 100 of 2020-22

- Top 75 of 2019

- Top 50 of 2018

- Top 75 of 2017

- Top 75 of 2016

- Top 75 of 2015

- Top 75 of 2014

- Top 35 of 2013

- Top 25 of 2012

- Top 10 of 2011

- Popular Sections:

- All-Time Top 500

- All the Boardgames I've Played

- All the Anime Series I've Seen

- All the Animated Films I've Seen

- Top 75 by Female Creators

- Kids Recommendations

- What I Read: A Reading Log

- Other Features:

- Bookclub Study Guides