Footnotes in Gaza

Letís be honest for a moment: the only thing I know about Willard Quine, the 20th century Harvard philosopher, is a tacit understanding of his idea of recalcitrant experiences. And, having picked it up in a casual conversation at a Thanksgiving party more than a decade ago, I may not even have that right.

The idea is that for normal experiences: 1) each person has created a complex web of beliefs that fit together in such a way as to support their perception of the world and 2) as new pieces of information are assimilated, they are woven into the web in such a way that the worldview is supported still more strongly. Recalcitrant experiences, however, are those pieces of new information that cannot be assimilated into the web and, because of this, shatter a portion of the web of belief to such a degree that it must be rewoven—a task that alters sometimes greatly the shape and pattern of that web (and therefore the worldview it supports). The end of the matter is that the worldview shifts in previously unexpected ways.

Reading the work of Joe Sacco was, for me, a recalcitrant experience.

Letís go back a decade or two to my formative experience in the Christian church. I grew up in Californiaís premiere non-denominational denomination. Calvary Chapel, an outgrowth of (and reaction to) the Four-Square tradition, is what one might call: very dispensational. For the unwary, dispensationalism is the complicated sort of interpretive rubric by which someone reads the Bible and comes up with an end-of-the-world scenario that resembles more or less that which I imagine was laid out in the Left Behind series.

As a teenager, it was not uncommon to see intricate charts illustrating all the maddening complexities of the eschatological framework that despotically governed our motivations. Much of what we did was in mind of the imminent rapture of the church and its concordant seven years of tribulation (with a capital T). And above all things in our late-twentieth-century world, there was one idea that was of the utmost importance: to bless Israel was to curry favour with God and to curse Israel was to invite wrath and judgment. And even thinking a negative thought about the nation skirted cursing Israel so closely as to be indistinguishable from it.

In point of fact, the Israeli nation could do no wrong.

Israel occupies a special place in the dispensational understanding of things. As opposed to other Christian perspectives, dispensationalism holds Israel and her children in such high esteem that Messianic Jews are often seen as some glorious chimera who, being Jews, likely hold the keys to interpreting all the particularly knotty issues the Scriptures hold. Maps in textbooks of the region called Palestine are edited with Sharpies to become maps of Israel. There is within dispensational circles some variety of opinion as to just how deeply those descended from Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob should be revered, but in common to the last man, American dispensationalists seem to be deeply fearful of the president who finally gives in to the powers of the world and decides to stop supporting Israel.

Such an action would surely lead to the ruin of the American nation. We would be cursed of God. We would flee in seven ways from before our enemies. The skies would be as bronze. There would be molds. Plural.

So then, what did Joe Sacco do? The first thing and the one that affected me recalcitrantly was craft a comic called Palestine.

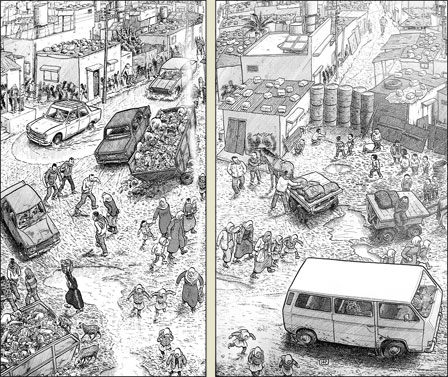

A typical day in Palestine

A typical day in Palestine

(click for larger)

Sacco is a special kind of journalist. Over the last fifteen years, heís produced book after book giving readers an up-close perspective of areas of the world torn by the kind of traumas that Americans will likely never have to face. At least not in our generation. Maybe in the next if they are especially unlucky.

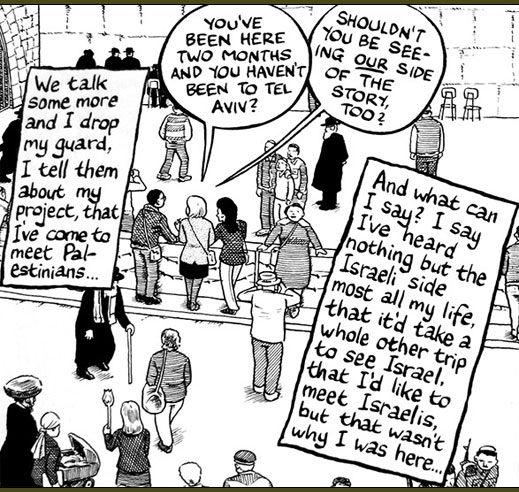

1999's Palestine is a sprawling, 288-page non-fictional comic book that chronicles Saccoís experience in Palestine at the tail end of the First Intifada (that is, the uprising of the Palestinian people against what they considered to be the oppressive Israeli regime—this lasted from 1987 through 1993). Sacco peppers his narrative with interview after interview, speaking to both Palestinians and Israelis, though spending more time on the Palestinian side of the equation. At one point he responds to a skeptical Israeli woman who wonders why he isnít more interested in interviewing Israelis, telling the reader that heís heard Israelís side of things his entire life.

I could relate.

Joe Sacco confesses the reason behind his biases

Joe Sacco confesses the reason behind his biases

(click for larger)

Ever since I was old enough to know that there was still a nation called Israel and old enough to know that there was a PLO and Arabs and a Palestinian people, I knew that Israel was the good guy and all those nations around them were the enemy who wanted Israel dead, who wanted Godís chosen people dead. There was no way I was able to process information that might portray Israel in a negative light save to either spin it positively or simply reject it as the, quote-unquote, Bias of the Liberal Media.

What? Israel attacked Palestine and a bunch of citizens were killed? Well, the Palestinians know that Israelís policy is to return an attack with a force greater than that with which they were attacked. They should just stop attacking! What? Israelís taking land from the Palestinians in order to house new Jewish immigrants? Well, it is their land after all. God did promise it to them. The Palestinians are just lucky the Israelis donít act like God commanded them to in the Old Testament. What? Israelís torturing and killing innocent people? In cold blood? Liberal lies.

Itís very easy to maintain a belief system when one is immune to new information. Of course, Saccoís Palestine hit me in a way I was totally unprepared for. Instead of railing against Israel, instead of merely exposing some of their more dubious methods of controlling the Palestinian people, it took a far more direct route. It did something I could never have expected or defended against.

Palestine humanized the people of Palestine.

It did the same for the Israelis, sure, but in my mind they were already quite human. It was the Palestinians who were essentially kobolds or orcs, fantastic creatures whose whole existence was devoted to hoping for Israelís destruction. Yet Sacco unveils a people rich in culture, grievously wronged by world powers generations earlier, and presently stuck in circumstances with no ready solution. Their populace is as varied in its opinions, beliefs, and desires as is our own. Some wanted peace at all costs. Some wanted a fair and equitable resolution to the conflict. Some wanted reparations. And some wanted war so badly that it hurts. These were people with dreams and nightmares. People governed by hope and by hopelessness.

These were, whether I liked it or not, people.

And so, Joe Sacco, with a single book, turned my ability to (mis)understand Israelís place in the Middle East on its ear. Suddenly I was able to hear things I had been previously deaf to. I was able at last to empathize with the plights of my brothers and sisters who happen to be Palestinian. More, I became able to empathize with people in a vast array of cultures that had previously been marginalized by my theological framework. By the time I had read Palestine, I had abandoned my infatuation with dispensationalism a couple years earlier but had still retained my warm-hearted sentiment toward the Israeli nation. I canít imagine how chaotic this shift in thinking would have been had I still held doggedly to the dispensational system.

Still, that was years ago. And really, not much has changed in the Palestinian/Israeli relationship. Palestinians still feel oppressed (and rightly so) and lob bombs into Israel destroying the lives of random people with mothers and children and lovers; and Israelis still feel attacked (and rightly so) and shoot missiles into Palestine destroying the lives of random people with mothers and children and lovers. The tragic circle of self-perpetuated war and terror continues and my anger at both groups swells like the tides under a full moon. So why bring this up now?

After several excellent journalistic comics featuring the Bosnian war and its aftermath, Sacco returns once more to the Palestinian conflict. And this time he has a far more specific goal in mind. Footnotes in Gaza, at 432 lushly illustrated pages, offers a new avenue for Americans who support Israel unreservedly to experience a paradigm shift and the opportunity to experience the conflict from the eyes of those who hold a perspective unique from anything we could ever muster on our own.

In Footnotes, Sacco splits time between present-day Gaza (that is, 2003—these things take a long time to draw) and Gaza in 1956 where he hopes to unveil the truth behind two massacres the Israelis purportedly carried out against Palestinian civilians at the end of the Suez Crisis. In the present day, Sacco moves from contact to contact with his guide and advisor, Abed, as they seek out anyone who lived through the terrible events. Along the way, Sacco treats subjects as various as the mindset of insurgents, the demolition of Palestinian homes at the edge of the refugee camps, the sheer mass of poverty these people experience, Palestinian reaction to American interventionism, and (briefly) the death of Rachel Corrie.

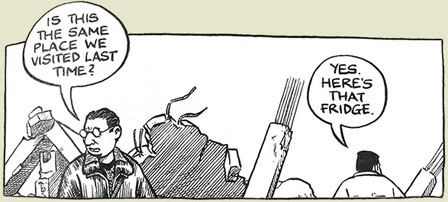

Joe and Abed tour the destroyed home they had visited weeks earlier

Joe and Abed tour the destroyed home they had visited weeks earlier

(click for larger)

As he slowly unveils what happened and what may have happened (Sacco is at all times circumspect about the fact that his interviewees are all very old and that their stories oftentimes conflict), weíre given a sense of just how desperate the situation isónot for the region but for the people. What is so often lost in the news reports we hear from Gaza is that these terrible circumstances are not just part of a larger political struggle and the ways of nations, but that these horrors are the fabric from which individual human lives are cut. If not for the hand of a fate that we can neither predict nor understand, that could be my mother whose leg was blown off in the most recent shelling. That could be my daughter who was killed in a Palestinian incursion. That could be my home being demolished suddenly for no better reason than that it provides decent cover for potential insurrectionists.

A woman speaks of the shelling that she and her

A woman speaks of the shelling that she and her

sister fell prey to the previous night while running an errand

(click for larger)

In Footnotes, Sacco proves that he is becoming better and better at what he does. Prior books Palestine and Safe Area: Gorazde are both fantastic treatments of their unique subjects, but with his present work, Sacco shows a lot of narrative growth. The book is hard and unrelenting and funny and insightfulóand the way Sacco threads the whole thing together speaks to the fact that he is becoming a master at the craft.

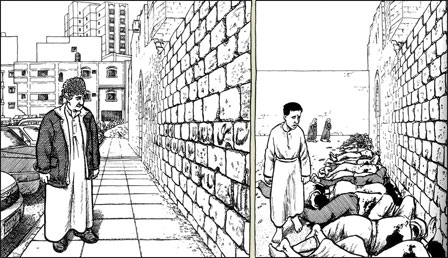

Faris Barbakh as an old man remembering the massacre

Faris Barbakh as an old man remembering the massacre

at Khan Younis as a fourteen-year-old in 1956

(click for larger)

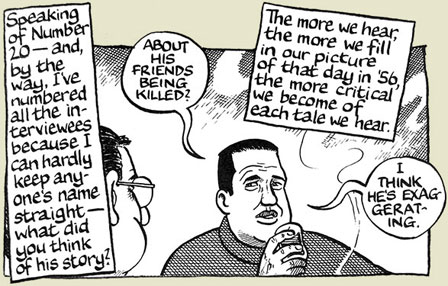

There have been criticisms that Sacco is too biased toward the plight of the Palestinians and that Footnotes is clearly a work of propaganda. These arguments however show that either the critics failed to actually read the work or they were so ready to assign the author blame that they missed the nuance that carries Sacco through his endeavor. The author continually remarks at how little verifiable information they have on these massacres. He notes baldly his skepticism toward a number of interviewers. He records with faithfulness the distasteful rhetoric of some of his contacts (e.g. those who wish for more suicide bombings and those who wish for the destruction of America). He records the Israeli perspective of how and why certain things happened. Or even if they happened.

Joe and Abed contemplate the uncertainties that plague all historians

Joe and Abed contemplate the uncertainties that plague all historians

(click for larger)

Joe Sacco, like everyone, has his sympathies, but they certainly should not get in the way of this beautifully rendered, thoughtful remark upon a situation that is even now tearing at the seams of the world and baffling world leaders who want to see it end but can puzzle out no easy solution.

I try not to read Saccoís books too often because they tear at my soul. My first reaction is rage and fury, but then I recall that this entire situation is built on the stuff. Rage and fury never solved these kinds of conflict. And so, instead I am overcome by grief and a sadness that I am completely powerless to protect these people, to offer them any kind of real support (beyond educating myself and those within my circles). I try not to read Saccoís books too often, but I do read them because they are important and essential. They work to keep me human and they work to remind me that others are too. I think of the Palestinians (our brothers and sisters) who live under constant threat simply for the fact that they were born in the wrong place. I think: we can do better than this. We donít have to be so cruel and hateful and angry and greedy and terrifying. And then, I remember history and how if history teaches us anything, itís that there will be no end to this kind of horror save for the grave.

Good Ok Bad features reviews of comics, graphic novels, manga, et cetera using a rare and auspicious three-star rating system. Point systems are notoriously fiddly, so here it's been pared down to three simple possibilities:

3 Stars = Good

2 Stars = Ok

1 Star = Bad

I am Seth T. Hahne and these are my reviews.

Browse Reviews By

Other Features

- Best Books of the Year:

- Top 50 of 2024

- Top 50 of 2023

- Top 100 of 2020-22

- Top 75 of 2019

- Top 50 of 2018

- Top 75 of 2017

- Top 75 of 2016

- Top 75 of 2015

- Top 75 of 2014

- Top 35 of 2013

- Top 25 of 2012

- Top 10 of 2011

- Popular Sections:

- All-Time Top 500

- All the Boardgames I've Played

- All the Anime Series I've Seen

- All the Animated Films I've Seen

- Top 75 by Female Creators

- Kids Recommendations

- What I Read: A Reading Log

- Other Features:

- Bookclub Study Guides