Flowers of Evil, vols 1–5

[Note: in manga reviews, images are set to read from left to right.]

"These kings of the sky, clumsy, ashamed."

—Baudelaire

The young teenage years are pretty much rough on everyone. Forget all the body weirdness—the growing boobs, getting hairy nuts, the changing voice, the blood, the acne. Forget all that awful, awkward business about having a body that's transitioning from its sensible kid form into what will eventually come to be the slightly more stable form of the adult person. And forget the fact that with your new limbs and protrusions, your balance is completely off and even the way you used to walk has to be relearned and reapplied because you're in a different chassis than you were, and because you haven't quite caught up, you're clumsy as a yak in an America shop. Forget all that because as traumatic as that can be and almost certainly is, it's amateur hour when stood against the wall in a police line-up with the psychological and ideological shifts that govern that same period of our lives.

Or at least that govern the lives of people who are like me. And like the principal characters of Shūzō Oshimi's Flowers of Evil. I don't believe we're special either. I suspect these shifts time their approach as arm-in-arm escorts of puberty, honoured guests to the marriage of the self-consciousness and self-awareness that mark our first steps toward adulthood.

Self-awareness vs self-consciousness! Now fight!

Self-awareness vs self-consciousness! Now fight!

At some point along the winding path between immaturity and maturity, the human child (with few exceptions) becomes first cognizant of themselves as unique person and then of themselves as they may be viewed by others. Often, the time that passes between "Hey wait! I am totally unique and a person in my own right and I can do and believe as I want!" and "Omigosh, probably everyone will hate me!" is pretty slim. For me, it was a near instantaneous revelation. I mean, I knew before that point that some people didn't like me, but it was always distanced from who I was inside. Up until that shift in self-awareness, that some people picked on me just seemed like bad luck—like some people got the raw end and that was just kind of a matter left to the Norns. Or something. Obviously, as I wasn't yet entirely self-aware, I wasn't thinking in these kinds of terms. But regardless, I didn't recognize a huge connection between how I was treated and who I was.

"Those damaged products of a good-for-nothing age."

—Baudelaire

Simultaneously, many of us struggle with the recognition that the world is messed up and suddenly we have minds that will someday (maybe even tomorrow) be able to grasp some of the reasons why. We see, at least in part, the errors and hypocrisies of the older generations. We see parents who aren't doing anything to make things better, who aren't rocking the boat for change. (Because they're likely too busy paying for our food and our clothes and our schooling and our housing and our entertainment, but we're not yet aware enough to see how that sucks the soul out of even the best of us.) We see these atrocities against the idealist human spirit and we reject at least a portion of what came before us. This is why so many junior high fantasies turn toward what we on the outside perceive as darkness.11Incidentally, this reaction repeats itself often again in college, only with a more positive social aura. The young teen has typically had his extended moment of angst over the fact that the world sold is not as advertised. By high school, much of that sense of revolution and need for social alteration has been supplanted by the necessity of survival. Social survival, yes, but nonetheless. The hierarchy of high school life asserts so much centripetal force against the gravity of our social spheres that any lack of focus can send us, it seems at the time, spiraling out of orbit and into dark loneliness.

That sense tends to pass in college, where social circles are generally more fluid and less hierarchical. And with the advent of higher education in the mind-life of a young adult, suddenly awareness blossoms to the fore again. We come once more to the stark recognition of the abject failure of our forebears—and once more to the sense that we might be able to correct the errors that made our world. Rather than bloom in darkness, we flower into idealism. And we never realize that our window for change is as small as it was when we were naive teens.

The college experience is perhaps the last time until retirement that this opportunity exists. Most students are still living on their parents' dime and so have the luxury of reckless living and reckless thought. Soon enough though their lives will be wholly their own responsibility and the necessity of survival will once more overrule them—even as it did their parents and their parents' parents. Hooray for the unending power that life holds in destroying idealism. There's this sensed need for the razing of the inequities and absurdities of the present age so that we might, even if only accidentally, emerge with something closer to utopian.

Part of this often impotent dissatisfaction with the way the world is manifests in teens finding (or believing they find) value in things that others do not. This can take the form of pursuing what are perceived to be fringe trends or marked interest in something old and off the cultural radar. Readers tend to take the latter path and so tend to express down more interesting lines—if no more rigourous or effective. There's something deliciously elitist about quote-unquote discovering some forgotten book or author, some writer of ideas that nobody you know is familiar with. When I was younger I read a biography of Rommel, a 700-page book of moralistic principles by Richard Baxter, and a Japanese novel by a first-time female author about a kid who killed his dad with a katana and hid the body. I felt awesome. I mean, what non-military-historian reads Rommel's biography? I had Arrived.

I mean, of course I was a moron. But that's part of growing up, right—the journey of learning that being elite just means that you have an unrealistic understanding of your own personal value and tastes. And just as I grew up and out of much of my small-mindedness and ridiculous sense of self-worth, so too will Flowers of Evil's protagonist, Takao Kasuga. At least, if Nakamura lets him live that long. In a way, though, Kasuga's relationship with Nakamura has put him on a bit of a fast track for moving toward maturity. He won't get there the normal way, but barring the cataclysmic, he'll likely get there sooner than the average bear.

"Ennui, the fruit of dismal apathy,

Becomes as large as immortality."—Baudelaire

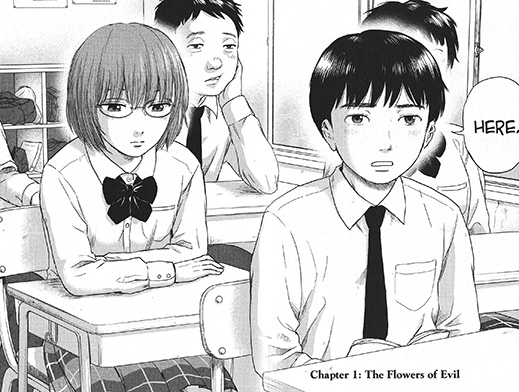

Flowers of Evil is a mix between romcom and bildungsroman (as most bildungsroman are). Kasuga finds himself struggling to adulthood on the social outskirts of acceptable junior-high society. He's still well-within the fold, careful not to step too far out of line, but his adoration of literature (especially foreign literature) sets him apart from his classmates. Behind him sits Sawa Nakamura, a girl with little regard to the manner of the world around her. She stares down teachers, calls them shit-bugs in front of the class, and delights in the possibility of what she sees as true perversion—not that amateur-hour sexual deviancy stuff, but the real deal: a twisting rejection of all that her society deems acceptable and normative. Kasuga falls under the misanthropic tutelage of Nakamura when she witnesses him nearly accidentally steal the gym clothes of Nanako Saeki, on whom he's had a monster crush for over a year. Kasuga begins capitulating to Nakamura's ludicrous demands under threat that his indiscretion will be revealed to Saeki. Buoyed by the strength he finds in the writings of Baudelaire, Kasuga follows the rabbit hole as far as he can, and soon enough Saeki herself is inevitably involved—forming a kind of insane love triangle. The whole thing is just bazonkers.

Oshimi's unwary protagonist finds satisfaction in an elitism marked especially by his love for Baudelaire's Les Fleurs du mal. Kasuga looks out over his rural town and pities it for its lack of sophistication. Of all the places he looks, he can find no one whom he believes would have read Baudelaire.22The notable exception is his father, with whom he shares a book collection. Their reading overlaps and his father reads anything Kasuga brings home and loans Kasuga whatever he picks up himself. The difference between the two becomes pronounced when it's made clear that the father reads for the enjoyment of the reading while the son reads for self-affirmation. Kasuga lives as though he has an ally in his father, but suspects the distinction between them—and this of course plays part in the evolution of Oshimi's potboiling storyline. He even has to travel to a distant neighbourhood to access a worthwhile bookstore that will carry the highbrow imports he revels in.

When I first approached Flowers of Evil, I suspected that Kasuga's infatuation with Baudelaire was incidental to the French author himself and to the specifics of the referenced work, Les Fleurs du mal. Oftentimes, the name-dropping of authors or exterior works fulfills the singular function of giving a character an air of pretension. And certainly Kasuga is pretentious. He adores Les Fleurs du mal primarily for how it makes him feel at odds with (and so, better than) the society in which he finds himself. But for that goal, any author obscure to a fourteen-year-old in the Japanese countryside could have worked. Kierkegaard, Pascal, Cicero, Hume, Joyce. It needn't have even been an author. Kieślowski or Eisenstein or Malick for film. Sienkiewisc or Gauguin or Man Ray for art. If all that was needed was a name to drop, any of these would have sufficed.33However, the idea of Kasuga calling out to Jelly Roll Morton for moral encouragement in times of anxiety does give me giggle fits. "Jelly Roll Morton!! Give me strength!!!" Oshimi does, however, seem to be aiming at more than mere pretension and his use of Baudelaire seems more nuanced.

I now speak as an expert on Les Fleurs du mal who had read neither it nor anything of Baudelaire until yesterday afternoon. Since then, I read the SparkNotes analysis as well as about five of the hundred-or-so poems included in the controversial collection. So I know what I'm talking about, clearly.

Nevertheless, reading that analysis and several poems did a lot for governing my understanding of the foundation from which Kasuga is operating at the book's start. It goes a long way toward both explaining why he often reacts the way that he does to Nakamura's and Saeki's actions and enforcing Nakamura's ideological plane as a natural place of safety for Kasuga.44And of course none of that means anything to you if you haven't yet read any of Flowers of Evil.

One of the primary themes Baudelaire plays with is the ground between what he terms Ideal and Spleen. The Ideal is basically what it sounds like, the inviolable purity of nobility and love and passion. The ideal is beautiful and honourable and, in Baudelaire's sense, fantasy. The Spleen is perhaps more easily represented by a sense of malaise. The Spleen is anger and filth and human muck. Weakness, greed, cowardice, lust, all the negative traits of the human spirit that rule us while ever preventing the Ideal from becoming reality. Baudelaire seems (so far as my expert limited reading implies) to be concerned with the tension between the two.

And as a bit of a dilettante, Kasuga seems less concerned with or even aware of that tension. He begins the book entranced by the darkness he sees swirling within it. Just reading Baudelaire's words at his desk at school feels to him subversive. Kasuga is drawn to the Ideal certainly, as evidenced by the positioning of Saeki (his crush) as his muse—wholly pure, incorruptible, sexy but without either sexual volition or sexual desire. The stark unrealism he indulges with relation to the girl seems ludicrous apart from the filter of Les Fleurs du mal's influence (and maybe even with that influence). Simultaneously, Kasuga wallows in his sense of the world's "evil." He doesn't so much recognize the troubles that plague humanity as he finds the concepts of evil (including rebellion and darkness and perversion) attractive—so long as they aren't in any way tied to Saeki, his muse.

"Adorable sorceress, do you love the damned?"

—Baudelaire

Nakamura seems a kind of bridge across the tension that Baudelaire expresses. She rejects Baudelaire and the contents of Les Fleurs du mal out of hand. She finds in Kasuga a good kind of clay to sculpt with, but wants to free him from his reliance upon one more of what she would deem a shit-bug—those people trapped by smallness of mind in a world that could be so much more if perversion could reign.55And again, not anything like the sexual perversion, or hentai, as we might most immediately think of it. Nakamura does jest with Kasuga once that he must be a truly perverted soul if the idea of normal sex with Saeki is repellent to him (riffing on the idea that he will not brook consideration of Saeki in sexual terms at all)—but that's just Nakamura giving Kasuga a hard time. She herself isn't really even interested in sex as a form of perversion at all (though she will abuse society's notions of sexual propriety to invoke her own concepts). Over the course of the series, Kasuga more and more finds Nakamura to be a marriage between Ideal and Spleen. Something glorious and beyond what he or Baudelaire may have conceived. Of course, he's just a naive fourteen-year-old, so what does he know?

Of the three characters, Saeki seems the most out of her depth. She's lived in quiet desperation for a long time but doesn't understand Nakamura's ideology or Kasuga's growing infatuation for it. In a way, she's the most level-headed of the group, but that leaves her the most vulnerable.66Incidentally, I would adore a series that took place concurrent to Flowers of Evil but was framed from Saeki's perspective. She's the most interesting to me and the one so far (by the end of volume 5) who's undergone the biggest paradigm shift. She also is the one with the most to lose if her play into these floral "evils" fails her. She's the good-looking girl at the top of the class, highly popular and destined to have a good future for all the connections her family can afford her. Kasuga on the other hand was never destined for greatness and Nakamura has, in a social sense, nothing to lose.

I don't know where Oshimi is going to take his story, but unless these characters succeed in remaking the world in a new image, they're bound to come out the other end damaged and perhaps beyond recognition. The series is still ongoing in Japan and I don't know how many volumes are intended. The arcs seem to move in threes (if the cover groupings are any indication) so the series may end with volume 9 or 12. In any case, that's plenty of time for the tone to shift dramatically in any direction. Maybe volume 7 will shoot us twenty years into a post-apocalyptic future in which Nakamura is an establishment nun for the Christian overchurch that governs all nations, Saeki is a part robot dominatrix, and Kasuga only exists as an embedded consciousness implanted in all sentient beings as part of a terrorist protocol initiated by Nakamura before her conversion. Or maybe things will continue hard-driving down a road paved on the bones of angels and we'll get to see the doom of three kids who relish the rejection of the normal so deeply that they alienate all around them. Really, anything kinda goes and I'm looking forward to seeing what happens and reading probably too much into it. I'm enthusiastic about this series even if it occasionally gives me the oogly-booglies (as in volume 5's crescendo).

There are a couple more things to discuss before I close. They just didn't fit so neatly in the stream of thoughts I had above, so I'll append them here.

Oshimi's art is kind of a chimera. In some ways it's brilliant. In others it's awkward and amateurish. I never don't like it, but it's got some rough edges. I'll talk about some of them before moving onto how awesome the art is. Easiest way is to show the big splash opener for volume 1.

Oshimi sometimes struggles with perspective and so renders his characters, like Nakamura here, with impossibly short limbs or too-large heads. If you're a fast reader, you can easily blow by these without concern, but those of us who like to luxuriate in an artist's choices might be stopped cold here and there while trying to understand what's going on and whether the figures are really disfigured. And here's a close-up on Kasuga's ears from the same page:

I don't know if Oshimi's own ears feature extreme protrusion of the antihelix, but he does this a lot with his characters as if it were normal. Every time a new character appeared with such aggressive antihelixes, I was torn from involvement in the narrative. It's not so much that I don't believe a bunch of unrelated people could have ears like that—but more just that I become deeply curious as to the motive behind the artistic choice.

Okay, so that's it for my complaints about Oshimi's illustrations. His choices otherwise all work spectacularly. Oshimi does a solid job conveying a breadth of emotions from boredom to suspicion to fear to anger to madness to anguish to cold criminal intent. Part of the reason I continued after the not-super-impressive first volume was Oshimi's ability to convey characters with depth and breadth. Half the story is told in words, but the better half perhaps is told in looks and body language. Oshimi, for the most part, nails this. Nakamura gives looks that exult in her moral superiority. We see Kasuga's soul die a little bit and resurrect as a new species of spirit. Saeki, when she is coy but clued in, looks exactly that.

Incidentally, with the importance of facial expression to the work, Oshimi makes an important design decision with regard to Nakamura. Nearly constantly wearing glasses could have easily saboutaged her entire character's visual strength, as glasses very neatly hide or obscure the eyes. And because the eyes play such an important role in Oshimi's manner of conveying expression, a Nakamura with diminished access to that method of facial storytelling would have been disastrous. Instead, Oshimi hides portions of the glasses that might interfere with Nakamura's expression. Often this will be the top rims of her frames, but sometimes he'll abolish other bits of the glasses' structure—as in this example in which Nakamura looks through one of the glasses' arms so that she can look from profile and the reader still knows exactly what she's expressing.

"The lady's maids, to whom every prince is handsome,

No longer can find gowns shameless enough

To wring a smile from this young skeleton. "—Baudelaire

Oshimi also uss art to heighten the sexual tension of the book and thereby includes and indicts, pressing the reader to share Kasuga's perspective. It's not fan service, meant to titillate the low-class kind of minor perverts that Nakamura dismisses with so much disgust. This is an entirely different kind of thing and, while it may be common, I hadn't personally seen the technique used before. Oshimi uses aspect-to-aspect panel transitions to paint the scene of interpersonal space in a setting. Very, very often, the reader will encounter a couple talking head panels followed by a panel featuring only Nakamura's bust or maybe the hem of Saeki's skirt. These are not generally remotely lurid—Nakamura's bust, for instance, usually features no cleavage and is almost formless in terms of detail—and seems present in order to convey Kasuga's awareness of sexual characteristics more than anything. Here's a two-page example in which Kasuga is having a conversation with Saeki on her sickbed while she is dressed in pajamas.

The presence of the panel featuring Saeki's crotch doesn't seem in place to spur the fantasies of Flowers of Evil's readership but instead to prompt us to empathize with the turmoil Kasuga is experiencing and give us a clue as to its origin in his own confused, virginal sexual nature.

A later scene set in the midst of a downpour capitalizes on this technique further. Nakamura, wearing only her school uniform, sits soaking beside a likewise wet Kasuga. Her shirt, as wet shirts will, become lightly translucent such that Kasuga can now make out Nakamura's bra. Kasuga's tension is immediately heightened the moment he becomes aware of this, but Nakamura remains nonplussed. While Kasuga is always aware of the sexual distinction between himself and his two friends, this event drives that difference home to him and firmly establishes him in the place of The Other amongst them. And while Oshimi could have played the scene for easy thrills with a leaning-in shot of cleavage or swell of breast, the whole thing is very subdued in those terms. There is plenty of thrill to be had in this episode, but not through the objectification of Nakamura.

e"And without drums or music, long hearses

Pass by slowly in my soul; Hope, vanquished,

Weeps, and atrocious, despotic Anguish

On my bowed skull plants her black flag."—Baudelaire

One of the most difficult scenes in the book so far is a rape built across the scope of a chapter. It's a hard circumstance to read through and could have easily been played for thrills. For the perpetrator, the act is a confluence of motives: fear, desire, confusion of identity, a need to feel important and wanted. Probably some other kinds of brokenness are at play as well. It's brutal and severing, the kind of thing that mars everything that takes place afterward. And the art used to depict this breach of faith is excellently composed.

The trouble with seeing depictions of rape is that unless obtusely coy, they are intrinsically erotic (cf nearly every classical sculpture or painting of the famous rapes of the Greek mythos). Naked bodies having sex, apart from context, is naturally sexual—and so, in some capacity, sexy. Add to this the problem that in this instance these are minors. A fourteen-year-old guy and a fourteen-year-old girl. It's a rough bet anyway you cut it.

Oshimi is explicit (in a sense) without being gratuitous. He plays it as sexual (and therefore, to some degree, sexy) without being lurid. There is frustration, anger, anguish, and erotic passion. For all the strangeness that makes this event even possible for these characters, it's all very human—and therefore, not simple at all. Part of what aids in this depiction is Oshimi's design choices. Considering his audience, he does blush away from stark portrayal. This is not an HBO series (yet). The girl's nipples are obscured, though areolae are hinted at and hand-bras are employed. The technique used to illustrate penetration is likewise coy, but incredibly apt and serves to magnify the tragedy the more. The whole scene is devastating and confusing and essential to the book's character-trajectory. I hated it, but because of how well done it and its immediate aftermath were, I also marveled at it. An incredible piece of work.

Still, as hard as this book can be at times, it's so far one of my favourites of the year. I don't know where it's going exactly, but with the building of the character foundations so far established, I'm hotly anticipating the journey Oshimi has prepared. These kids are trapped by the irony of their convictions, built of real dissatisfactions but expressed through the naïveté of youth and inexperience. Their end will almost certainly be tragic, but in the world of interesting fictions, who can really tell? These are characters invested with pronounced nobilities and evident flaws. Even Nakamura, whose confidence commands the spotlight, is shown as flawed and fallible, and the author doesn't pretend she is the paragon of a new order. In the five volumes so far, Oshimi has given us a series of increasingly turbulent interactions that build not just a framework for understanding the characters he works with but perhaps for understanding the turmoil of adolescence as well.

This book may be entirely bazonkers, but I am deeply invested and must see it through. For now, it gets my highest recommendation despite my discomfort with some of its expressions and my hopefully groundless fear that Oshimi may not actually end up creating something more than a reveling in sadism, masochism, and interpersonal anarchy.

Good Ok Bad features reviews of comics, graphic novels, manga, et cetera using a rare and auspicious three-star rating system. Point systems are notoriously fiddly, so here it's been pared down to three simple possibilities:

3 Stars = Good

2 Stars = Ok

1 Star = Bad

I am Seth T. Hahne and these are my reviews.

Browse Reviews By

Other Features

- Best Books of the Year:

- Top 50 of 2024

- Top 50 of 2023

- Top 100 of 2020-22

- Top 75 of 2019

- Top 50 of 2018

- Top 75 of 2017

- Top 75 of 2016

- Top 75 of 2015

- Top 75 of 2014

- Top 35 of 2013

- Top 25 of 2012

- Top 10 of 2011

- Popular Sections:

- All-Time Top 500

- All the Boardgames I've Played

- All the Anime Series I've Seen

- All the Animated Films I've Seen

- Top 75 by Female Creators

- Kids Recommendations

- What I Read: A Reading Log

- Other Features:

- Bookclub Study Guides