Duncan the Wonder Dog

Adam Hines is careful to avoid framing the discussion of animal and human interaction in terms of "rights." His concern is both semantic and philosophical. Rights, as he sees them, are human inventions, distributed capriciously as the human society sees fit. He sees no rigourous foundation upon which such a thing as rights can be grounded, so instead he hopes to recast the discussion to focus on animal welfare—which, to his mind, sits in a far more objective sphere than rights do. It's a careful distinction to make and Hines proves himself a careful author.

In fact, Hines takes such care with his story that the curiously named Duncan the Wonder Dog can be roundly considered a triumph of the medium. I've had the pleasure of reading a number of great books this last year, from Daytripper to Moving Pictures to Mother, Come Home to Elmer, and Duncan is quite possibly the best I've yet encountered. (It's a toss-up between that and the phenomenal Daytripper.)

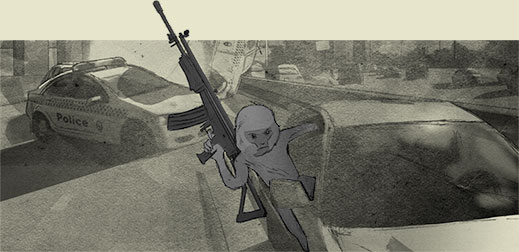

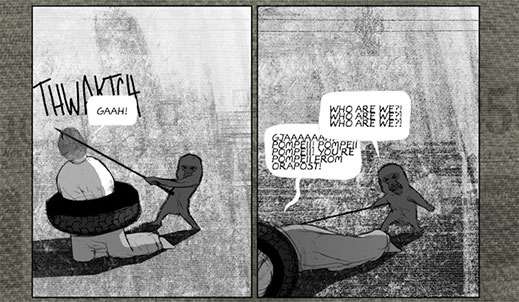

This is a picture of Pompeii, a monkey terrorist/animal rights activist,

This is a picture of Pompeii, a monkey terrorist/animal rights activist,

victoriously wielding automatic weaponry in the midst of a high-speed police chase.

That should be enough to sell eight million copies of this book.

I was hesitant to pick up Duncan the Wonder Dog for two reasons. The first is the title. One could be forgiven for finding it off-putting, trite, and childish. I really didn't have any desire to investigate a book that was a cartoonish serial adventure of some canine in a cape who solves mysteries and flies and maybe makes boo-boo-kitty eyes at a spaniel over a plate of back-alley pasta. The second obstacle was that I had already read Elmer and as that book explores a world in which chickens become sentient and uses the concept to tiptoe through some social issues, I felt I had met my talking-animals-versus-social-dilemmas quota.

Fortunately, neither of these monuments to my reluctance ended up keeping me from the book indefinitely.

Duncan is a large book, in a cornucopia of senses. Certainly its four hundred pages are impressive on their own, but Hines produces a product that expands along the other two common physical dimensions as well. The book—the first volume of a projected eight—carries the height and width of a standard sheet of American notebook paper: 8 ½" x 11". Being so large, the tome is naturally heavy as well, weighing nearly three pounds. And all of that merely touches on the book's physical imposition—where Duncan's true largeness is measured is in its content.

Hines crafts an expansive story with immense value against a tremendous ethical background on broad canvas. This is the story not of the human race but of creaturely existence. And co-existence. And through Hines' masterful technique Duncan—for all its fantastic setting—essays a profoundly moving, astonishing set of stories, each contributing to the question of co-existence in fresh, exciting ways.

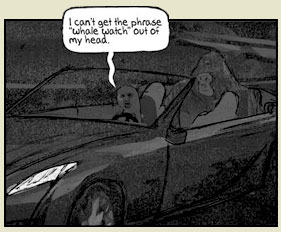

There are a number of horrificly tragic scenes in this book, but this one really hit me for its tit-for-tat retributive nature.

There are a number of horrificly tragic scenes in this book, but this one really hit me for its tit-for-tat retributive nature.

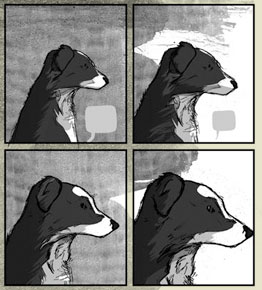

Duncan's structure is a slow-burn. At first it's not even clear that in this world animals can talk. And not just talk in that Watership Down sort of way, where animals have voices and can communicate amongst themselves but never to man. In Duncan the animals speak as plainly as you or I do. If you ask a whining dog what's the matter, she can simply tell you. Once it becomes clear that this is the kind of world that Hines is populating with his characters, a reader still has a hundred or so pages before the books' protagonists are firmly establish.

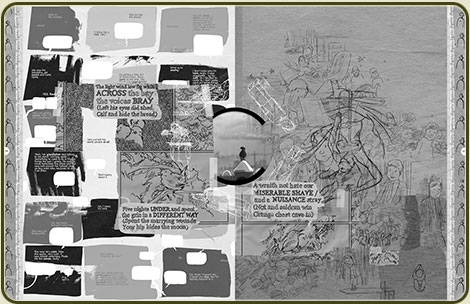

Hines uses a lot of collage throughout his book to give it a distinct aesthetic, but the form of collage extends even to his storytelling style. Despite the fact that the book does follow (probably) four main characters through its story, Hines takes frequent, numerous narrative breaks to focus on minor characters or even non-characters for a page or fifteen. Sometimes these excursions paint in an emotional palette while other examples feature a discussion of philosophy. I found myself conflicted, not wanting to be torn from whatever sidebar Hines had just introduced and the excitement of watching the main branch continue to unfurl. Hines balances between his subjects with a virtuosity one has to experience firsthand.

Hines here does a wonderful job conveying a man's life flashing before his eyes. Click to enlarge.

Hines here does a wonderful job conveying a man's life flashing before his eyes. Click to enlarge.

Duncan is a dense work. There are a lot of words on a lot of pages, but even more than that, Hines' pages of art demand scrutiny. His art serves his story and his story serves his art. It's possible that this volume represents the most ambitious use of the comics form yet. There may be other contenders, but I don't think I've seen them. This is a book that deserves second and third readings. Which makes it nice that the first reading was such an absolute pleasure.

Note:

I neglected to give any kind of summary of the book's plot or story conceit or anything that might hint at what Duncan the Wonder Dog is actually about. I'm not sure that it's even important for you to know. The book is that good. Good enough that you should go pick it up and sound out its reaches knowing nothing beyond the seal of its quality. Still, some may require a, quote-unquote, low-down.The world presented in Duncan is one that mirrors ours almost exactly—save for the fact that animals can express themselves in the language of humans. This doesn't change much about the world order. Cattle and pigs are still herded into pens and raised for the slaughter. Dogs and cats still live as pets. And foxes still prey on rabbits. The difference is that now the cows spread rumours about why none of them ever return after leaving for the slaughterhouse while the humans who are slaughtering them lie to them, explaining that the very idea of such murder houses is just silly. Animals (with a few humans) have formed activist groups, some of which have become full-blown terrorist cells. ORAPOST is one such group and it is helmed (for the moment at least) by a golden macaque named Pompeii whose attitude and methodology are as explosive as her name. It's a world with frayed edges, coming undone even as it seeks to forge itself into something worthwhile.

Hines offers the series online for free. The impressively sized bound volume is for sale, but Hines suggests that "if you are considering purchasing this book, please instead give that money" to one of a number of animal-friendly organizations. Only after you've done that does he present the idea that his book is actually for sale.

Good Ok Bad features reviews of comics, graphic novels, manga, et cetera using a rare and auspicious three-star rating system. Point systems are notoriously fiddly, so here it's been pared down to three simple possibilities:

3 Stars = Good

2 Stars = Ok

1 Star = Bad

I am Seth T. Hahne and these are my reviews.

Browse Reviews By

Other Features

- Best Books of the Year:

- Top 50 of 2024

- Top 50 of 2023

- Top 100 of 2020-22

- Top 75 of 2019

- Top 50 of 2018

- Top 75 of 2017

- Top 75 of 2016

- Top 75 of 2015

- Top 75 of 2014

- Top 35 of 2013

- Top 25 of 2012

- Top 10 of 2011

- Popular Sections:

- All-Time Top 500

- All the Boardgames I've Played

- All the Anime Series I've Seen

- All the Animated Films I've Seen

- Top 75 by Female Creators

- Kids Recommendations

- What I Read: A Reading Log

- Other Features:

- Bookclub Study Guides