Domu

It's a little bit sad to me that many or even most of the people who know the name Katsuhiro Otomo will likely only know him for his sprawling vision for a post-apocalyptic Neo Tokyo, as found in Akira. In a way, that's kind of like saying that it's sad that most people will only ever know Herman Melville for Moby Dick. That is: it's not really sad at all and that there is a good reason why the great torrential works are the ones that imprint on the shared cultural experience. There is a reason why when someone mentions Melville, Murakami, or Tolkien, better than nine-tenths of the time, that person isn't going to bring up (respectively) "Bartleby the Scrivener," Sputnik Sweetheart, or Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. And there is a reason that when people talk Otomo, it's a safe bet they aren't bringing up Domu.

And it has nothing to do with the quality of the work. Really, pound for pound, I find Domu a more exciting read packed with more thrills and better character moments than Akira. It's more tightly plotted and possibly even more insane, though I wouldn't argue the latter with any ferocity. There's just, perhaps, a feeling that we owe the larger work our fidelity simply for the tremendous effort involved. 2666 is the superior work because it's a bazillion pages long. Moby Dick is the superior work because it's a bazillion pages long. Akira is the superior work because it's longer than Moby Dick and 2666 put together in some glorious back-alley slash-fiction disaster by Melville and Bolaño's ferociously ugly in vitro lovechild.

Because I've a touch of the contrarian in me, I have to guard against preferring the lesser known work for virtue of its obscurity. I prefer Domu to Akira, but do I do so justly? It's hard to say. I mean, how could I ever know? In the end, the question might not even be worth asking, Which Is Better? Instead, the more worthwhile route may be simply to suggest that whatever the merits of the longer work—however completely awesome Akira might be11And Akira *is* awesome, of course. Every month in 1990 featured me hotly anticipating the next gorgeously coloured issue from Marvel's Epic line. I loved the heck out of Akira. Even the bizarro film adaptation.—Domu is wholly on its own merits worth the time it takes to track down the book and settle into its wacky brand of urban horror.

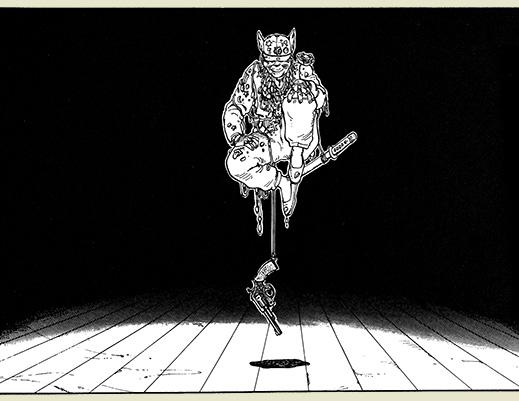

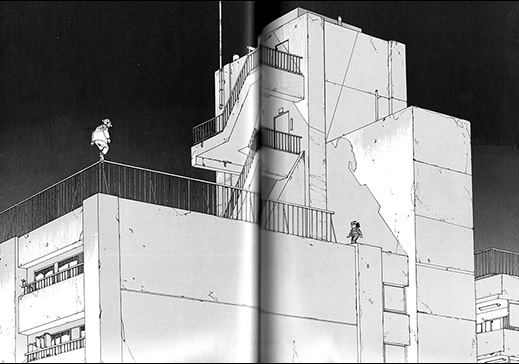

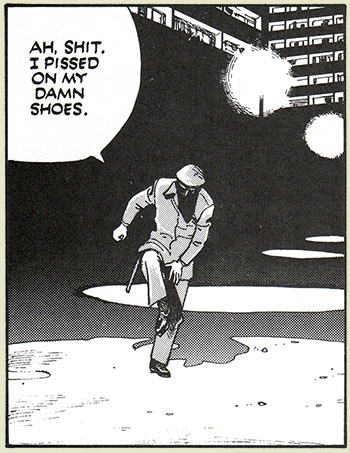

The lion's portion of what makes Domu so incredible is Otomo's artistic vision for the book. Not entirely of course, and the script is tightly plotted and wonderful, but Domu would not have been half so successful a realization of Otomo's story had it not been for his prodigious talent with a pen or brush. Here. Look at this panel.

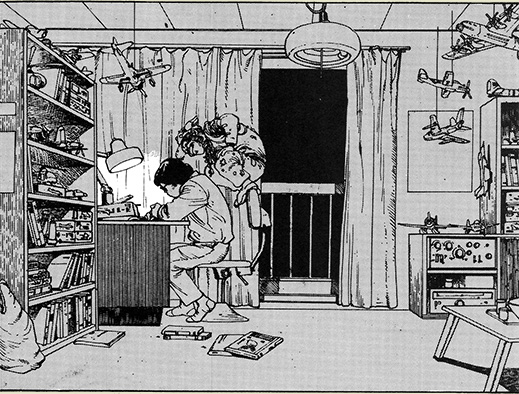

And now this.

And now this.

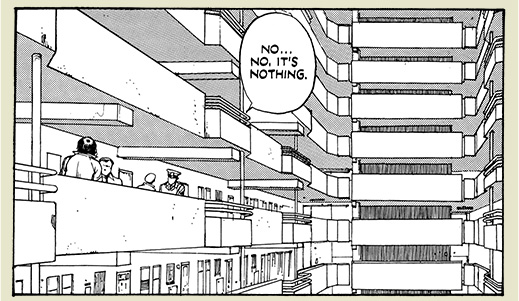

Check out the detail on this apartment complex. Before computers.

Check out the detail on this apartment complex. Before computers.

Do you feel bad yet for being nowhere near so accomplished in whatever skill it is that you have professed to become an expert in? Otomo may not be as awesome a father to my children as I am, but I am not near so awesome a father to my children as he is an illustrator. Probably the most painful thing about it is how little of Otomo's work there actually is. Like, imagine if Hayao Miyazaki's last film was Porco Rosso. We'd be thankful for what we had, of course, but in our heart of hearts we'd always be mournful for what was never made.33I actually feel like this pretty much constantly for the premature loss of Satoshi Kon.

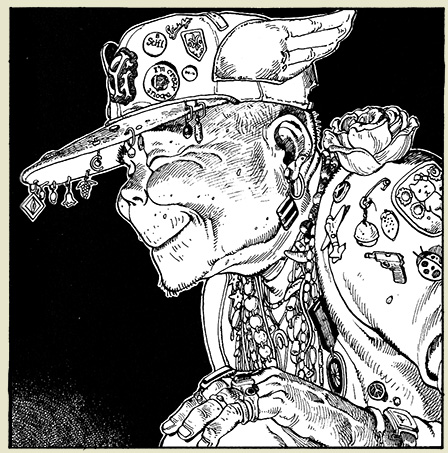

And really, it's not even all down to the intricacy of his work either. His sense of design is impeccable. You know how there are a few directors/cinematographers who just bear astonishing aptitude for their work, who shoot angles and vistas that eclipse the actors themselves. That's Otomo. Think back on the work of Sergio Leone. The Good, the Bad & the Ugly.44Even more apt, actually, is Once Upon a Time in the West, but too few have seen it. Nearly fifty years after The Good, the Bad & the Ugly and too few have seen even that, so it seems a vain hope to figure on the contemporary reader being conversant with Leone's superior-though-less popular film. But suppose you were familiar with it, think back on how the opening seven minutes nearly dominates entirely the three hours that follow. There is nearly no dialogue. Just three men waiting for a train. But through his command of sight and sound Leone crafts one of the most maddeningly memorable sequences in cinematic history. Sure, the film stars cinematic superstars Clint Eastwood, Lee Van Cleef, and Eli Wallach, but without Leone's peculiar framing, long posed shots, and extreme close-ups (remember the final duel and the combatants' eyes), the film would have been inert. That is what Otomo offers his characters. The chance to be enveloped in something preordained in such a way as to show off every facet in its most dynamic and awestriking light.

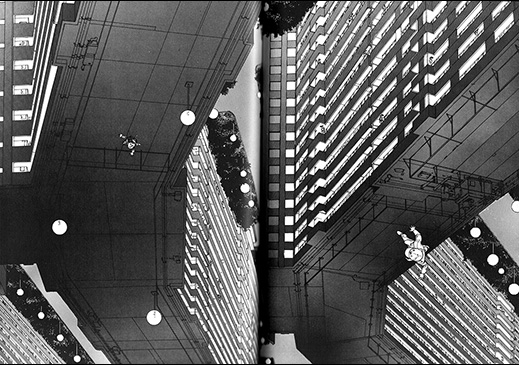

Again, an example.

2-Page spread—hence the weird scanner stuff at the crease.

2-Page spread—hence the weird scanner stuff at the crease.

And another.

2-Page spread—hence the weird scnner stuff at the crease.

2-Page spread—hence the weird scnner stuff at the crease.

Also, Otomo here vertically flips the orientation so that the gound is at the top of the page and the sky at bottom. We see the rooftops with lamps on top. The two figures twist in the air high above the complex.

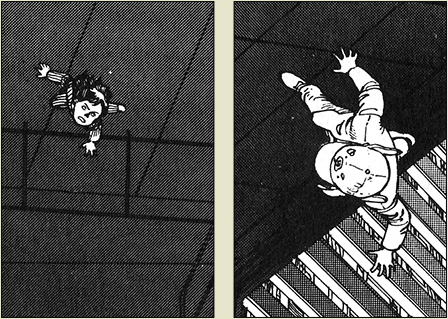

Close-up on Etsuko and Old Cho.

Close-up on Etsuko and Old Cho.

And one more.

This is Otomo's version of Leone's gunfights.

This is Otomo's version of Leone's gunfights.

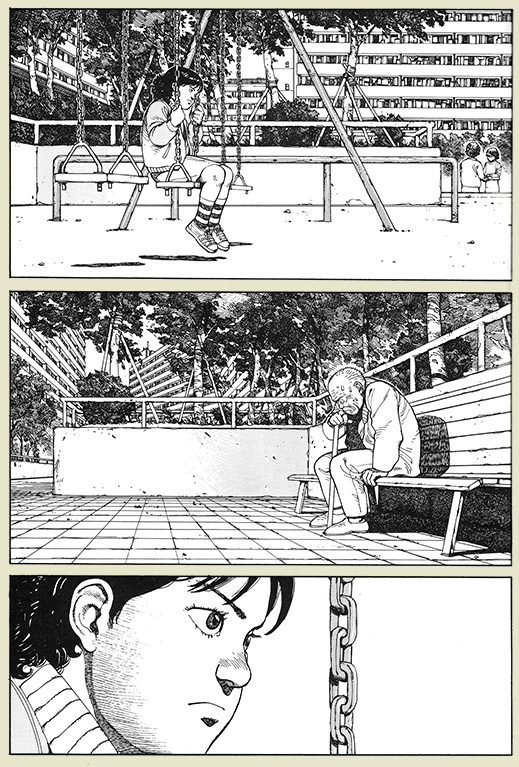

And interestingly, Otomo's ability to convey action so dynamically capitalizes dramatically on his story's sense of irony. Beyond the horror aspect of the book, Otomo presents a story deeply concerned with futility—which plays on his character's extreme impotence. Of all Domu's characters, so many of whom try so hard to effect their own destinies, only two (and then, really only one) ever have any ability to affect the outcome of the book's machinations. The crazy woman, the mentally arrested giant, the hoodlum, the kid, the young detective, the chief detective, the spiritist. They're each incompetent to alter their own destinies and the destinies around them. Domu focuses heavily on police work and the reader spends a lot of time following an investigation that will ultimately be resolved in the most delicious deus ex machina—and by an unlikely deus.

The lighting choices here are phenomenal.

The lighting choices here are phenomenal.

Domu is an almost perfect work. It may actually be perfect. I don't really have the apparatus to judge perfection, so I tend to talk in aimless vagaries like this. Whether perfect or not, the sheer talent invested into its every page is formidable and affecting. It's easy to see, for instance, how Domu might have influenced Rian Johnson in his execution of Looper's Rainmaker character—one could easily guess that Etsuko stepped right out of Otomo's Tokyo's high-rise developments and into Johnson's Midwestern cornfields. When I first encountered Domu fifteen years ago, I was certain the book would stick with me throughout my life. I've been right so far. It is after all a masterwork, so we shouldn't be surprised.

Good Ok Bad features reviews of comics, graphic novels, manga, et cetera using a rare and auspicious three-star rating system. Point systems are notoriously fiddly, so here it's been pared down to three simple possibilities:

3 Stars = Good

2 Stars = Ok

1 Star = Bad

I am Seth T. Hahne and these are my reviews.

Browse Reviews By

Other Features

- Best Books of the Year:

- Top 50 of 2024

- Top 50 of 2023

- Top 100 of 2020-22

- Top 75 of 2019

- Top 50 of 2018

- Top 75 of 2017

- Top 75 of 2016

- Top 75 of 2015

- Top 75 of 2014

- Top 35 of 2013

- Top 25 of 2012

- Top 10 of 2011

- Popular Sections:

- All-Time Top 500

- All the Boardgames I've Played

- All the Anime Series I've Seen

- All the Animated Films I've Seen

- Top 75 by Female Creators

- Kids Recommendations

- What I Read: A Reading Log

- Other Features:

- Bookclub Study Guides