The Boxer

Here in the post-colonial democratic West, bastion of liberty and freedom and justice for all, the human identity is derived by one of three formulae. An American will be a product of either a) the decisions and circumstances of their past, b) the actions and position of the present, or c) the person one hopes to be in the near or distant future. Other cultures may offer additional options—an identity might, for instance, be derived from the community rather than the individual—but parcel and part to the American dream is the demand that we narrowly define ourselves according to the true and tried pieces and bits of the three basic tenses.

It's a struggle through which we move from pessimist to pragmatist to idealist even as our outlook shifts from past to present to future. And of course it's not always a progression. Some of us will remain wholly enveloped in nostalgia, the essentially pessimistic view of the world that looks to the past for identity rather than engage the present or hope for the future. Others will embrace the identity of the moment, a wholly utilitarian device for exercising immediate control over one's person and outlook—often in the guise of realism. The third group of us looks, fingers-crossed, forward to the us that we strive to be (or at least presume to hope to be), and rest our identity in that hypothetical us that may never come to be.

Harry "Herschel" Haft ping-pongs a bit between the three options, but—as we might expect from a survivor of the Third Reich's death camps—the once-smuggler, then-boxer, then-grocer spends significant portions of his life being identified by his past. Even as he prepares to disembark onto American shores for the first time, Harry is overwhelmed by turbulent visions from his time in front of Nazi ovens. Inconspicuous moments are haunted by the memories from which his own personal history snakes out to grip him by the throat, offering both paralysis and catalyst. This is Harry at his most American. Occasionally spurred by a kind of romanticism and glimpsing a self he hoped to one day inhabit, Harry throws himself into his boxing—all to the end of finding again the love of his life and making true the faery tale. Only by beating and clawing at the lives of others will he be positioned to take on the identity he dreams for himself. This is Harry at his most American. Finally, the boxer surrenders his dreams to what he imagines must be reality. He takes up a new daily struggle and throws himself into the most immediate of concerns: food, shelter, companionship, progeny. His dreams no longer control him, his past no longer commands him. He is wholly devoted to the now. This is Harry at his most American.

Though of course it isn't all so simple as that. Even while Harry is who he is in the present, he cannot shake the ghost of the past—ghosts that twist his dreams for the future. The former boxer is harried by the life he once hoped to live and those dreams built of a busted prescience only work to diminish the identity he finally settles into. He's a man torn at by invented creatures beyond his control, and he is weak in the face of them. Yet simultaneously, this man—this boxer—is full of spit and fire and fight. And that's actually where half the wonder of Kleist's work resides.

You may as well discover my filthy secret now. I go out of my way to avoid Holocaust narrative. It's not so much that I pretend that so many Jews, Romani, handicapped, and poor didn't die all because a nation of people couldn't any longer imagine itself to be poor and so would rather light the world afire, grabbing what they could in the chaos. That's not what it is at all. It's more just that I've been devastated by the story already. Over and over again. It was an important component in my public school education. We read books, heard stories, saw pictures, and met survivors. I've read Maus, seen Life Is Beautiful, read Anne Frank and Eli Wiesel, and seen Schindler's List and Judgment at Nuremberg and The Hiding Place. I have been properly horrified over and over again. By the end of junior high, I never wanted to study the subject again—I was full up. And yet, I was returned to the Holocaust over and over. There's only so much bludgeoning one can take before one's heart begins to curdle. So I don't seek out Holocaust stories anymore and, often, if I'm aware that's what a direction will get me, I will choose a different path.11I was given the opportunity to read Loïc Dauvillier's graphic novel hidden, and I took one look at these two pages and backed right the heck out of there immediately. I'm sure it's a wonderful and valuable and important work. But I couldn't do it. Even these two lone pages crushed me.

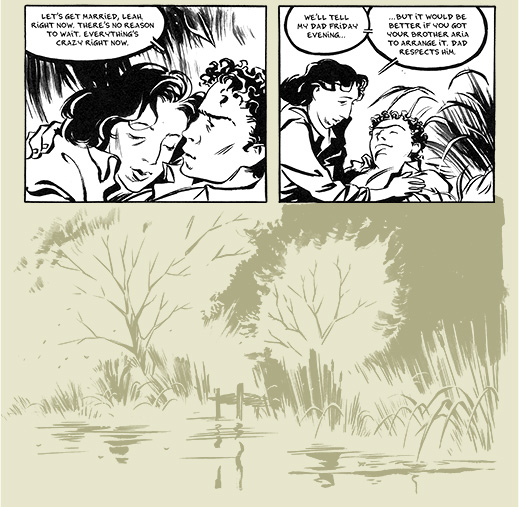

When I bought The Boxer I didn't know its relation to WWII or the Holocaust.22 I also don't read sports narratives that aren't written by Mitsuru Adachi, but I'd heard fantastic things about Kleist, so I made an exception. When it arrived, I saw the concentration camp on the cover and dejectedly let the book sit on the mail pile for a week. At last though (obviously) I resolved to give the book a shot at weaning me from my terror. And Harry Haft succeeded. Wildly, too.

The difference is one of spirit. The Holocaust tale is one of broken hearts and spirits, of human persons reduced to walking ghosts. It's terror after terror and it breaks everyone, rendering them into the soulless. Beyond even the deaths and murders and rapes and incinerations and gassings, probably the thing that devastates me so entirely is the iron work of destruction the Nazi machine wreaks on the souls of their victims in these stories. Perfectly believable, sure; yet not something I want to see more than a handful of times. Haft, however, is a pugilist. And even if he isn't yet a boxer when he gets dragged to the camps, he's born a fighter. He's got spirit and its nigh unquenchable. The Nazis will go to great lengths to diminish Haft, to strip him of his inner fire; they will essentially destroy him and ruin him for all time. But it will take something greater than Hitler's mania to turn Haft into the living dead. Because he fights and fights and fights.

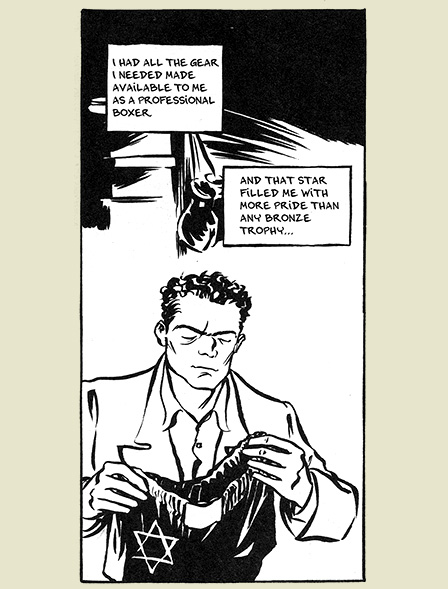

Even when he establishes himself in the US boxing circuit, Haft makes certain his boxing trunks are decorated with a Star of David. This could easily be seen wholly as a redemption and repurposement of the star that was used to damn the Jews not even a decade earlier, but there's more to it than just that. The five-pointed pentagram, associated with Daivd's royal son, is called the Star of Solomon; it's the hexagram that is David's star. And while both kings, Solomon and David, carry their measure of historical fame in the Jewish mythos, David was the warrior—so bloody-handed and vicious in battle that he was forbidden from building a temple for Yahweh by Yahweh himself. Solomon's reign, on the other hand, was marked by peace, prosperity, and leisure. Solomon's star could never suit Haft for Harry is every bit the tortured warrior and fighter that King David would have been.

So when we see in The Boxer's opening pages that Haft is broken and crazy, we are driven to find out why. It's a perfect opening, especially as Kleist immediately juts back to fourteen-year-old Harry (then named Hertzko), full of piss and fire and life. It's a fantastic setup and by the time Kleist catches us up again to the Harry Haft revealed in the opening pages, it all clicks. We're sold entirely on the tragedy and victory of his life. All things have come to resolution and we are satisfied.

I'd never encountered a book by Reinhard Kleist before this week. I'm only a little bit upset at myself for that. Mostly I'm just happy that now I have a nice little bibliography to discover—because I'm definitely interested in exploring more of the man's work. His art is fluid, organic, and pretty wonderful. He captures Haft so so well at all kinds of ages and in all kinds of conditions. Young teen, twenty-year-old boxer, fifty-year old man, Holocaust-starved teen, distraught, angry, deliriously happy. Under Kleist's brush Haft always looks like Haft—even when he's almost entirely another person. Whether past, present, or future, whichever Haft Harry chooses to be in a moment, Kleist makes certain the soul remains bubbling and fighting below the surface, unquenched. It's a fantastic exercise and Kleist delivers both a Holocaust narrative that has something new to say and a personal history that succeeds in making its hero intriguing without lionizing him.

Good Ok Bad features reviews of comics, graphic novels, manga, et cetera using a rare and auspicious three-star rating system. Point systems are notoriously fiddly, so here it's been pared down to three simple possibilities:

3 Stars = Good

2 Stars = Ok

1 Star = Bad

I am Seth T. Hahne and these are my reviews.

Browse Reviews By

Other Features

- Best Books of the Year:

- Top 50 of 2024

- Top 50 of 2023

- Top 100 of 2020-22

- Top 75 of 2019

- Top 50 of 2018

- Top 75 of 2017

- Top 75 of 2016

- Top 75 of 2015

- Top 75 of 2014

- Top 35 of 2013

- Top 25 of 2012

- Top 10 of 2011

- Popular Sections:

- All-Time Top 500

- All the Boardgames I've Played

- All the Anime Series I've Seen

- All the Animated Films I've Seen

- Top 75 by Female Creators

- Kids Recommendations

- What I Read: A Reading Log

- Other Features:

- Bookclub Study Guides