Blue

My old home, my old home...

My old home, my old home...

Growing up at El Morro in Southern California, a point break that hit beautifully on a south swell, I had the pleasure of an easy intimacy with the ocean. Growing up the son of a hippie surfer-artist, who surfs even to this day, I had the pleasure of ready access to Surfer Magazine. And to Surfing—and I confess to not knowing the difference between the two. At least one of them had surf comics in them. I grew up seeing the work of Bob Penuelas and Rick Griffin (who pretty clearly inspired Penuelas). I, from my childhood environment, had everything I needed to appreciate Pat Grant's 21st century extrapolation of the surfer-art movements of the prior century.

But because Grant's Blue is much more than a exultation in wave-riding, I am fortunate that I've had other human experiences as well. Well, fortunate perhaps only in that I can relate to the experiential bones on which Blue's narrative musculature is hinged. When I was a kid, there was a short tunnel that passed under PCH11PCH stands for Pacific Coast Highway, aka the 1 or Highway 1, a length of road that runs nearly the length of the California coast. connecting my neighbourhood directly to the sand at El Morro Beach. It was sprayed entirely by talentless graffiti that focused largely around the concept of: CDM FAGS GO HOME. CDM referred to Corona Del Mar, the town a five-minute drive immediately to the north along PCH. Localism was fierce, as it is at probably every beach.22Localism was fierce, as it is at probably every beach.As every surf break only allows a limited number of waves per hour and only a small fraction of those are set waves, competition for those waves can be tough. With locals, an uneasy hierarchy might form so that the top dogs get the best waves and leave the scraps for those lower on the totem pole. In more egalitarian surf societies, a lineup will form, granting access to waves on a first-come-first-served basis. In either case, waves are a limited commodity and if additional bodies are jockeying for rides, those local to the break are going to be getting fewer rides than they would otherwise. Hence a traditional and culturally institutionalized animosity toward visitors, tourists, non-locals. And Blue, more than even an exploration of Australian youth surf culture, is a pericope cut from the human society's natural antipathy toward the stranger.

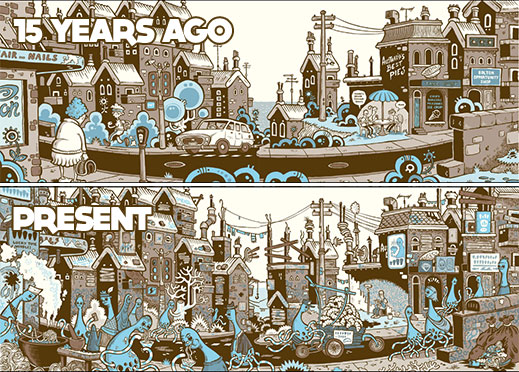

In Blue, Pat Grant allows the grown-up version of a surf rat named Christian to narrate the changes that have taken place over the fifteen years since a new kind of foreigner began trickling onto Northern Australian shores. It's fascinating because Grant allows his protagonist to hold all manner of distasteful fears and opinions while simultaneously vindicating some of his protagonist's views. It's a delicate procedure, but I think it pays off. Greg Burgas was less sure and found Grant's unwillingness to condemn his lead's prejudices to make uncomfortable reading. I can see where Burgas is coming from, but I think that Grant's book gives the reader an opportunity to explore not just Christian's prejudices but their own as well.

In extended, almost book-length flashback (acknowledged to be like Stand By Me in several ways), Grant introduces the book's principal foreigners as blue-skinned, four-legged, alien-looking beings who propagate graffiti at alarming rates, have awkward fashion sense, and are careless with their littering. Between the time of their arrival and the setting of Christian's narration, the town of Bolton goes from a thriving town and 1989 Tidytown Winner to a broken down village entirely covered by graffiti and dominated by noodle shops, a favourite cultural food of the blue people (who are now the majority population).

And here's the trick Grant plays on readers. In Christian's view (and quite possibly from the view of Grant's readers), the shift from Tidytown to Graffititown is a deeply negative experience—and proof that unchecked immigration is Bad. Where Blue offers the reader the opportunity to self-examine is in considering the same world from the vantage of the blue people. Grant is careful to humanize the foreigners through cues rooted even within Christian's prejudiced narrative. We see the blue people's attempts at assimilation and the loneliness in an orphaned blue child. Grant gives the blue people a mortality that mirrors the mortality of the native white Australian (we see a description of a dead body visualized as a non-foreigner, but when it is discovered to be a foreigner, it looks the same but is coloured blue).

So then, the question: in the view of the blue people, is the town better or worse than it was fifteen years ago? Plausibly, the blue people would say it's better, more comfortable, and more in line with their cultural tastes. So who then is to say that the Tidytown version of Bolton was the better iteration? Whose culture gets to play arbiter? Grant makes it clear that adding new individuals to a society will alter culture within that society33Grant makes it clear that adding new individuals to a society will alter culture within that society.It's a facile point but one worth making since in trying to be welcoming to newcomers, we often gloss over the changes they will necessarily bring with them. It may be that our fear of causing offense or being seen as bigoted may cause us to pretend that stimulus to a system won't affect the system. and that those comfortable within a society are going to suffer some measure of change.

And in any case, the damage to the Tidytown facade is showing even before the mass immigration strikes. Each of Christian's friends and Christian himself are the opposite of tidy, living in personal squalor. Christian's house is a disaster and its walls cracked and failing. To remember Bolton as a paradise is to remember a lie.

That Grant gives us the tools to investigate one of Blue's primary theses (that newcomers change community cultures in ways that may be perceived negatively) but doesn't tell us what to think was refreshing to me. In a way, it's fitting that Craig Thompson should have endorsed the book because I felt much the same with his Habibi, a complex work that doesn't outright condemn much but offers readers the opportunity to join a conversation. Blue has a lot of little things to say that pile up into maybe a large thing. The trick, then, is partially in unraveling what Grant himself is saying through his wonderful pictures, but probably more importantly unraveling what you may be saying to yourself in the midst of reading his work.

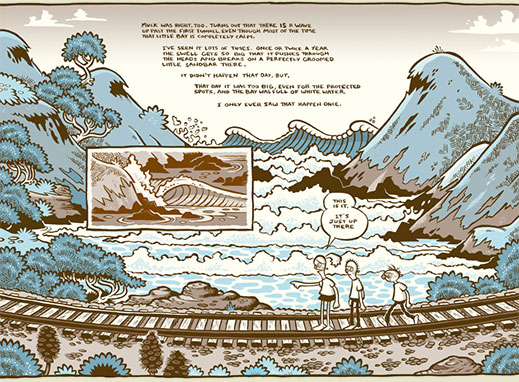

This is actually a pretty cool page. The brown panel in the middle is meant to show the same spot on another day, when there were flawless sets and no chop.

This is actually a pretty cool page. The brown panel in the middle is meant to show the same spot on another day, when there were flawless sets and no chop.

A Word on the Art

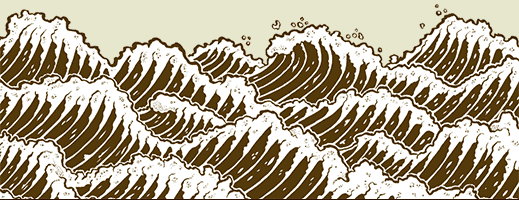

The above was actually going to be the conclusion of my review but I found it offensive that I hadn't yet mentioned Grant's superb art. His environmental sense is incredible and he uses his pages' paneling to lay out his story in inventive, evocative ways. His treatment of the natural world is lush, wild, and important—even as he shows the foreignness of the blue people within Bolton's society, he makes the Australian seem even more the foreigner when dwarfed by the wildness of the forest or the tumult of the sea. Grant's lines are thick and powerful and his work owes a clear debt to Rick Griffin (a debt he acknowledges in a wonderful afterward, playing with the history of surf comics and especially Australian surf comics). His palette consists of black-and-white, spare shades of brown, and spare shades of blue—and he doesn't need anything else. He uses these to virtuosically play his themes (locals and tourists) off each other. It really works.

Notes

PCH stands for Pacific Coast Highway, aka the 1 or Highway 1, a length of road that runs nearly the length of the California coast.

-

Localism was fierce, as it is at probably every beach.

As every surf break only allows a limited number of waves per hour and only a small fraction of those are set waves, competition for those waves can be tough. With locals, an uneasy hierarchy might form so that the top dogs get the best waves and leave the scraps for those lower on the totem pole. In more egalitarian surf societies, a first-come-first-served lineup will form, granting access to waves on a first-come-first-served basis. In either case, waves are a limited commodity and if additional bodies are jockeying for rides, those local to the break are going to be getting fewer rides than they would otherwise. Hence a traditional and culturally institutionalized animosity toward visitors, tourists, non-locals.

-

Grant makes it clear that adding new individuals to a society will alter culture within that society.

It's a facile point but one worth making since in trying to be welcoming to newcomers, we often gloss over the changes they will necessarily bring with them. It may be that our fear of causing offense or being seen as bigoted may cause us to pretend that stimulus to a system won't affect the system.

Good Ok Bad features reviews of comics, graphic novels, manga, et cetera using a rare and auspicious three-star rating system. Point systems are notoriously fiddly, so here it's been pared down to three simple possibilities:

3 Stars = Good

2 Stars = Ok

1 Star = Bad

I am Seth T. Hahne and these are my reviews.

Browse Reviews By

Other Features

- Best Books of the Year:

- Top 50 of 2024

- Top 50 of 2023

- Top 100 of 2020-22

- Top 75 of 2019

- Top 50 of 2018

- Top 75 of 2017

- Top 75 of 2016

- Top 75 of 2015

- Top 75 of 2014

- Top 35 of 2013

- Top 25 of 2012

- Top 10 of 2011

- Popular Sections:

- All-Time Top 500

- All the Boardgames I've Played

- All the Anime Series I've Seen

- All the Animated Films I've Seen

- Top 75 by Female Creators

- Kids Recommendations

- What I Read: A Reading Log

- Other Features:

- Bookclub Study Guides