Let's shake things up a smidgen. Just a little. You won't mind, I don't think.

I won't lie. The cult of the new has got me down, and I think about it more and more every passing while. We miss so much by focusing wholly on what came out in this last year. These lists read more and more to me like evidence of missed opportunities rather than any kind of collation of the best of the medium released in any given circuit around the sun. The number of truly wonderful books that don't get any recognition in the year they're released is probably bigger than you think, definitely bigger than I want.

As a case in point, nobody put Joshua Cotter's Nod Away, vol 2 in their best-of list in 2021, and it was easily one of the best comics of the past few years—I had it as №2 in my 2020-2022 list. People are talking about it more now, but it took more than that first year to gather any steam. Other books like Ordinary Victories and Aya Love In Yop City didn't make my own lists because I'd read them the year after they were released.

This is, I think, a problem. Not a big problem, but unlike the *actually* big problems, it is a) one that affects me in some way and b) one that I can take some small action toward a remedy.

So for this year's list, I'll be doing the Top 50 books I read for the first time in 2023 (or well, in the year since I last made a Good Ok Bad list). This way, I get to celebrate older comics I've encountered for the first time alongside great books published in the last year. For those who still really want to know what on this list is new, I'll include a little 2023 badge.

The one funny thing now is that my reason for publishing a list in February has vanished. Previously, I'd waited 'til February every year so that I could cram in as many last minute reads from December and November and catch as many stragglers in the name of due diligence, remedying somewhat the substantial problem I have with best-of-year lists that hit in early December, namely that they have to pretend that all the best books have already come out and been read by critics.

So now, I have 2024 books creeping into my 2023 round-up. Solutions making new problems! Anyway, please now enjoy reading about some pretty great books.

Oh, but one other thing before we hit the list. I make comics! A lot of you probably already knew that, but some might be surprised (after all, they're indie enough that having one published by Koyama or Peow or Shortbox or Avery Hill would feel like a Big AAA Production. These are mostly just low-key affairs, short dips into Exactly The Kind Of Comics I Like, so they've definitely probably got limited appeal. But I think they're pretty rad because, like, I would, wouldn't I?

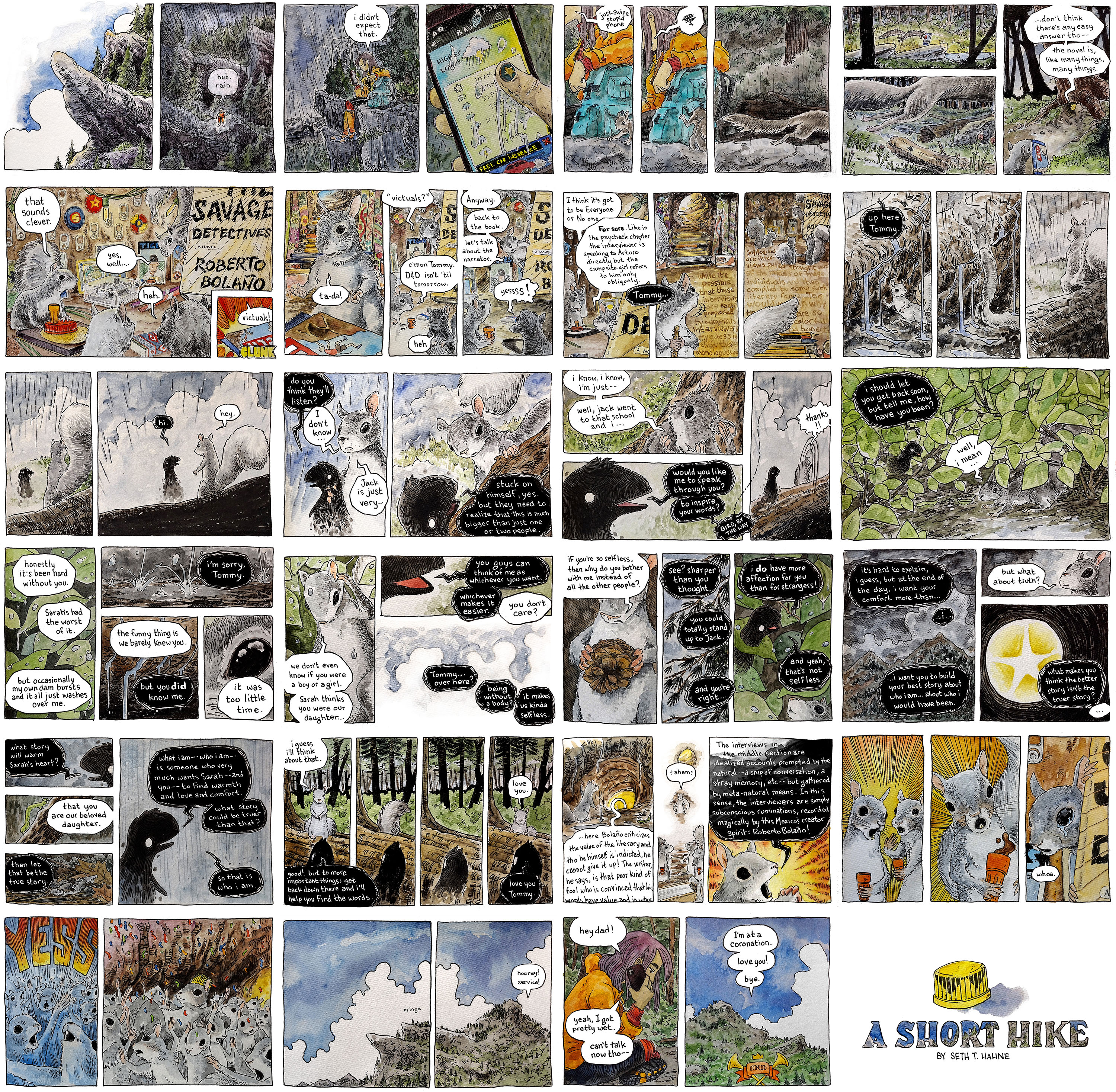

Anyway, I've been drawing comics for 10 years now in the spare corners of my time, and in 2023 I made my 16th comic, a 24-page book called A Short Hike about life on the mountain, loss, the nature of book club politics, and whether ghosts want anything at all. While physical copies exist, I'd love for you to read it, so you can check it out for free here:

Additionally, in 2023, I began work on the follow-up to my children's graphic novel, Monkess The Homunculus. Work on the book is sporadic and I won't be finished for a few more months, but here's the first 48 pages if you'd like to check that out:

My approximation of self-promotion out of the way, here's 50 great comics that you've already read or will maybe like to think about reading. At the end of the day, this isn't about upsetting anyone because their favorite from 2023 isn't included. Instead this is just one more opportunity to celebrate comics and remember what a wonderfully diverse, robust, and warm-hearted artform we've inherited.

SupportProse I ReadNavel Gazing

My Best 50 Comics of 2023

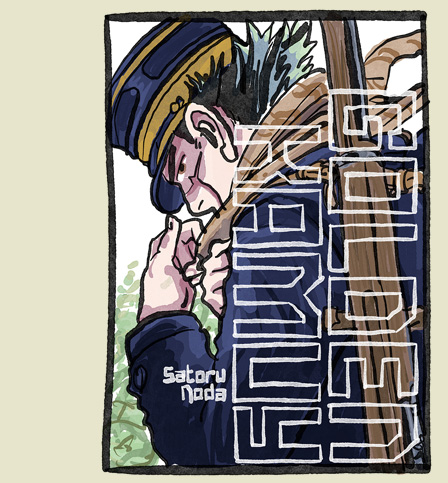

Golden Kamuy

by Satoru Noda (translated by John Werry, lettered by Steven Dutro)

31 vols

Published by Viz

ISBN: 1974741796 (Amazon)

Satoru Noda finally wrapped his 31-volume exploration of post-war gold-hunters, the plight of the indigenous, and hilariously depraved but often lovable lunatics—and boy howdy is this comics.

Golden Kamuy is one of the strangest, most wonderful adventure stories I've seen. It's terrifically violent, terrifically educational, and terrifically funny. I'd underestimated just how funny, lulled into thinking it would just be an educational adventure romp by the first several volumes that keep the humor subdued and almost rare. Noda's definitely got comedic use of expression down to a science untouched by other human hands, but his comic timing is impeccable as well. Possibly the funniest non-comedy book out there, maybe even funnier than Cross Game (blasphemy, I know), but possibly also funnier than most of the best actual comedy books as well.

Here's a brief synopsis that won't remotely capture the magic of the book but will give you a place to hang your hat, I guess. Sugimoto is a veteran of the recent (1904-05) Russo-Japanese War, come to Hokkaido in a gold rush hoping to make some money to cover an eye surgery for his former lover and wife of his KIA best friend. While trying and failing at panning, Sugimoto accidents into an intrigue involving twenty or so tattoo'd convicts whose tattoos comprise a map to an army-raising pile of gold. Sugimoto teams with a young indigenous Ainu girl to race against a few other much better organized factions to reassamble the map and find the gold (and maybe start a rebellion). Also: the map tattoos are meant to be assembled by skinning the convicts to put it all together, so...

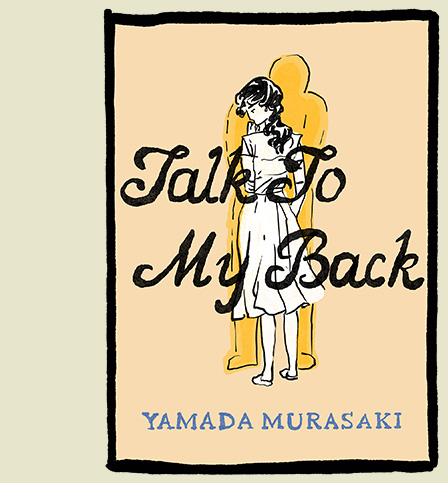

Talk To My Back

by Murasaki Yamada (translated by Ryan Holmberg)

368 pages

Published by Drawn & Quarterly

ISBN: 1770465634 (Amazon)

I'm not, I think, a turd husband. Not in any Big or Substantial ways. My turdliness, I think, is less to do with my husbandness or my man-ness and more in line with my human-ness. At least if you ask me. Ask my wife and the answer might differ. Which is kind of the point to Talk To My Back.

Yamada's book offers a series of vignettes over the course of three or four years of a young woman's life, a housewife in her 30s and mother of two girls. She spends her days serving her family and through the narration comments on her state and ruminates about the morality of the patriarchal social system she finds herself bound by. Her husband is a turd and a heel, but expects fidelity and support. He has come to care little for any of her needs save for how her mood will affect his treatment at home—and even there he is negligent and aloof.

Talk To My Back is beautifully written and drawn and offered me a welcome opportunity for self-interrogation. Yes, I'm not a turd husband, sure. Easy to say, easy to dismiss. I don't fail my wife and children in the ways that this guy does and I won't ever fail in the way this guy does, but in how many thousands of similar ways am I inadequate to the people I propose to love? How often do I accidentally weaponize my illnesses and infirmities and exhaustion, putting work into the hands of others? How often do I just need a little break, pretending for fifteen minutes or so that my little break isn't putting work onto someone who would also love a fifteen minute break? How often do I wait to be asked to do something rather than take responsibility for the life I've lucked into? The answer to all of these is something like Not always but often enough that I should do better. For her, for them, for me.

I'd like to keep Talk To My Back around as a reminder not to take the people in my life for granted. I'm grateful to have read it. I'm sad Ms. Yamada is no longer with us because I'd love to have been able to let her know how important I found her book.

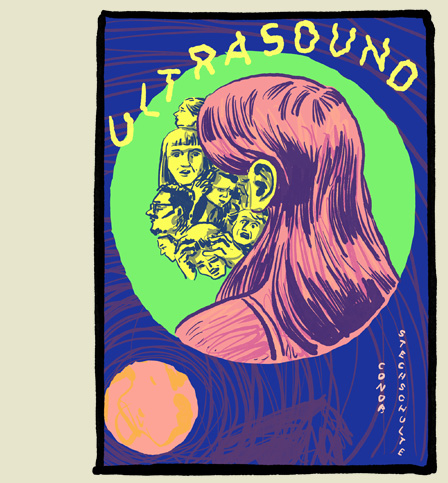

Ultrasound

by Conor Stechschulte

376 pages

Published by Fantagraphics

ISBN: 1683965345 (Amazon)

Ultrasound is a torrent of visual ideas. It's also a jumpy turn-twist of a turn-twist of a story where knowing what's going on is never really at stake. It's a book that washes you all over with a spray of visual hypersense while it lies to you over and over again. The lies are the point and, while invigourating, still the least interesting thing about the book.

Reality overlays reality, and even from the opening page's four-piece set of identical panels depicting a rain-drenched rural road decreasingly double-exposed over a scene in a bar, we begin to recognize that taking things for granted (and perhaps making sense of things at all) is the provence of the illiterate. "Wait, what?" should be a common prayer incensing from any of the book's readers, careful or not.

But yes, though reiterative mistrust is the governing motif—and a worthy place to hang your hat—that "Wait, what?" should feel like nothing compared to the "Oh wow!" you should more often be uttering as you take in all the tricks of art and depiciton that Stechschulte tosses freely like the biblical Sower. I'm blown away by some of the simple things that dance on the stage Stechschulte's prepared.

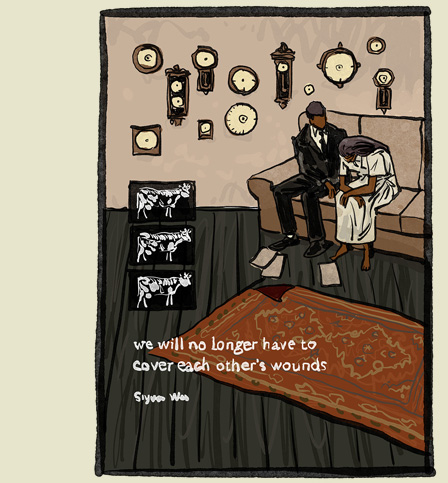

We Will No Longer Have to Cover Each Other's Wounds

by Siyuan Wen (translated by Runzelig Lou)

Published by Fieldmouse

ISBN: 978-1-956636-20-8 (Fieldmouse shop)

A book about grief between broken people and their broken relationships, Wen's book drips with imagery and abstraction, the talking about one thing by talking about another. It's the kind of book that the word "haunt" in all its tenses and cases was probably first intended. Haunted, haunting, haunts. Even a brief survey of reviews will bear this out.

Bombastically subdued (can I do that with words?), We Will No Longer... stimulates an interpretive apparatus in the reader that in most of us is probably a bit malnourished, a bit underused. There is an expansive world here, despite how little Happens. This is the kind of stuff that gets me excited to see where comics will take us next.

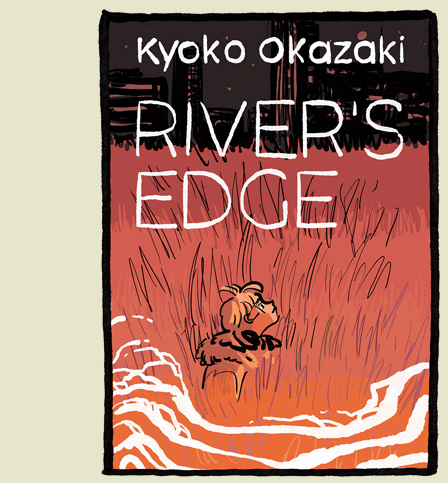

River's Edge

by Kyoko Okazaki (translated by Alexa Frank, lettered by who knows because this is a Vertical book)

242 pages

Published by Vertical

ISBN: 1647291836 (Amazon)

It's been nearly a decade since we've gotten any Okazaki in the US. An accident shattered her life in 1996 and it wasn't until 2013 that we got any of it (Helter Skelter and Pink), and then, nothing!

Now let's be clear. Okazaki is one of the wonders of the medium. Helter Skelter was a savage indictment of Japanese society in the '90s, and Pink was a blazing satire, funny and ludicrous. To have so little from her bibliography available is as criminal as having so little of Adachi's.

Finally though, River's Edge has arrived. And it's brutal and funny and anarchic and lovely. You know the criminal chaos of Stray Bullets in the '90s? Okazaki was doing the same thing only with interpersonal relationships (+comedy +crimes). But if Helter Skelter is critique and Pink is satire, then what is River's Edge? I don't know, I'm still working it out. Maybe just bald zeitgeist? Like Kids or something? I dunno.

In any case, it's wild and chaotic and brute force and funny and grim. In a lot of ways, it feels like Inio Asano if most of his books didn't vibe like paeans to edgelords. Or maybe it really is just closer to Lapham's worlds. Loved it in any case.

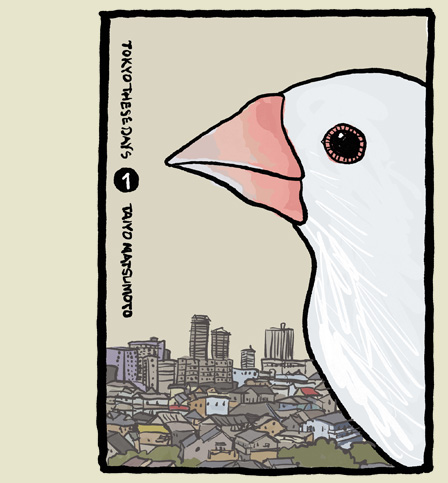

Tokyo These Days

by Taiyo Matsumoto (translated by Michael Arias, lettered by Deron Bennett)

1+ vols

Published by Viz

ISBN: 1974738809 (Amazon)

Tokyo These Days is like Sunny but with cartoonists and editors instead of with children in foster care. Tokyo These Days is like Ping Pong but with cartoonists and editors instead of with high school nerd sports. It's pretty rad.

Synopsis-wise, we've got a revered-but-maybe-passe comics editor whose retiring after his magazine baby where he Ikki-like showcases off-brand comics finally folds, unable to draw the necessary readers. He's a bit despondant, but then can't give up the horse* and so tries to gather an all-star collection of creators for one last score. As far as putting-the-band-back-together naratives, I'm absolutely hooked.

(*read: comics not heroin)

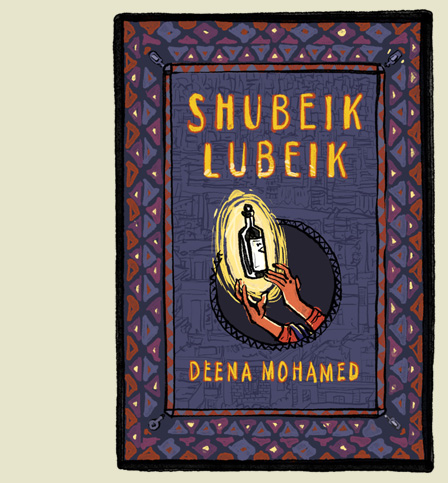

Shubeik Lubeik

by Deena Mohamed

528 pages

Published by Pantheon

ISBN: 1524748412 (Amazon)

Okay this is going to sound stupid, but it's been a year since I read Shubeik Lubeik and all kinds of the details and resonances and memories about how I felt and what I thought are lost to time. I didn't realize when I read it that it would be eligible for this year's list (because I didn't realize I'd be giving the finger to publication date), so I didn't write down any of my thoughts in order to spur later reflection.

That said. That said. I do remember that Shubeik Lubeik was one of my favorite reads. That I was smitten with its world-building, something that isn't very often enough to bowl me over. That I was deeply entranced by the three stories Mohamed blends together and how they pull themselves together to support the governing bookends.

I don't own the book (being a broke artist makes acquiring new books a tough prospect these days), but its a book I'm certain will be housed on my shelf in the future, after things y'know turn around for me.

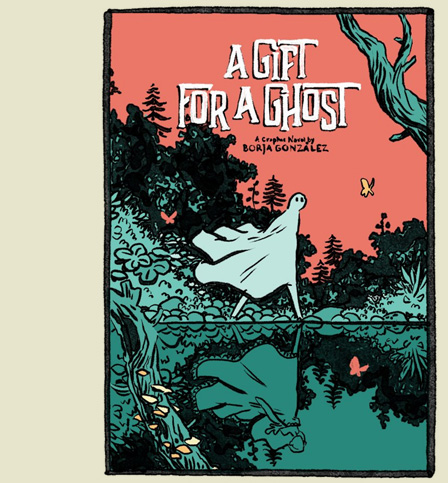

A Gift For A Ghost

by Borja Gonzalez (translated by Lee Douglas)

128 pages

Published by Harry N. Abrams

ISBN: 141974013X (Amazon)

I've read some good books in the last year, some really good books in fact. But nothing that looks as good as this cross-century non-sexual romance by Borja Gonzalez. It's like if you took height-of-his-powers Mignola, rounded off all the angularity, and then colored it in a limited-but-perfect otherworldly palette. Not every page is jaw-dropping. Some are merely rad or great. But every now and then, you run into a page that makes you think you're looking at heaven. Not a glimpse of heaven. Not Paul's visionary Third Heaven. No, just a casual inspection of the real thing. You'll swear you can hear the distant voices of angels or Bikini Kill.

There's a story in there too. One that reads like an ode to Kathryn Immonen, whom you know I love. And I don't want to say it's just there as a distraction. Say, rather, that it serves as a vehicle for an aesthetic ambassador sent from the Golden Realm, bringing us good tidings and a reason to hope.

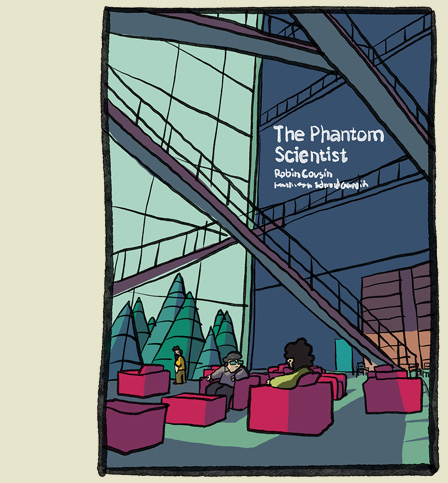

The Phantom Scientist

by Robin Cousin (translated by Edward Gauvin)

128 pages

Published by The MIT Press

ISBN: 0262047861 (Amazon)

This was my big find of the year. While Golden Kamuy remains among the best comics of the last five years and everything ahead of it on this list came pretty well recommended, I'd never heard of The Phantom Scientist before, simply discovering it by pulling it off the shelf and giving it a shot. It was like nothing I've read.

You know how a lot of books, movies, shows, etc concerning geniuses tell you how brilliant their characters are but don't ever really prove it? This is likely because the author wants to write about a supergenius but isn't themselves a supergenius, so they have to toss in some science words and hope you'll get the picture. The Phantom Scientist feels like it's actually about scientists because when they talk about stuff, it feels much closer to people talking about actual science. It could still be BS, but if so it's a class of BS orders higher than what we normally get.

Anyway, The Phantom Scientist is a weird little story about a weird little idea. Institute 4 is replacing Institute 3 hot on the heels of its inevitible collapse. Like, really hot on its heels. Institute 3 is being evacuated in chaos and while this is happening, the first resident scientist of Institute 4 is being welcomed to his new position. The institutes are meant as an ongoing experiment in organizational systems and why patterns of chaos predictibly follow a pattern.

I think I mostly kept up with the math and science it talked about, but it was the mystery and watching it unfold that ket me glued to the page.

Okinawa

by Susumu Higa

544 pages

Published by Fantagraphics

ISBN: 1683961188 (Amazon)

In Okinawa we find a record of life under a heel, under several really. Higa, a native Okinawan, spins out stories from the Battle Of Okinawa and then from fifty years later. Stories, yes. True stories, yes. Even if sometimes fictional. He catalogues ably the life of the Okinawans, their culture alien to Americans and Japanese alike, and what the contest for their island amidst the imperial machinations meant for their people. It's a book of joy, of comfort, of terror, of tragedy. It's what any book about people under war should be. In that, it's universal, but in that it's Higa's stories, Okinawa is unique.

One quarter of Okinawans died in the invasion of their island. It wasn't their war. But they were governed by their Japanese colonizers and told to defend their land from the Americans whom they were warned would do terrible things if they surrendered. The Americans both did not do terrible things but also did. They are, after all, still a heavy military presence. Okinawa takes its time with all of this, not just telling but unfurling relatable stories that give life and meaning to the Okinawan struggle under these two alien nations.

SupportProse I ReadNavel Gazing

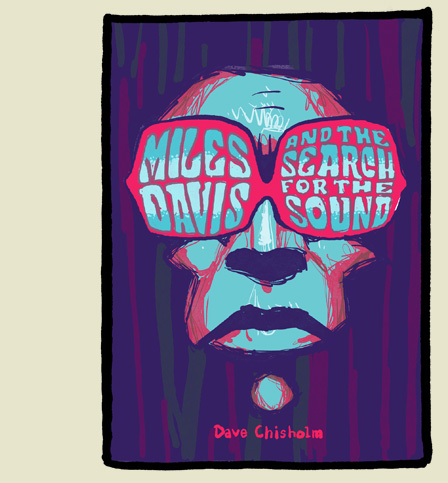

Miles Davis And The Search For The Sound

by Dave Chisholm

150 pages

Published by Z2 Comics

ISBN: 979-8886560428 (Amazon)

Dave Chisholm, man. This is that friend of yours who you played Vanilla WoW with every weekend in 2005. Every time you'd party up, he'd be a couple levels higher than the week before. He'd clearly been playing and having fun, but he wasn't a lifer. Last time you saw him was Sunday and he'd been rounding on level 30 with his human frost mage. Now, it's Saturday, six days later and suddenly he rides up on a mount—a mount!!—and he's level 41! What on earth? Where did he find the time? Is this all he did? What even --?!

This is Dave Chisholm. He'd been putting out a steady stream of fun jazz-forward comics. Instrumental. Chasin' The Bird. Enter The Blue. With each new book, you could see improvement. Real, visible, honest improvement. A testament to putting in the work. Then you hear about Miles Davis and you're pretty stoked because the trend says this'll be his best yet. Then you crack it open and a frost mage almost rides you down on his shiny new horse. I mean, jeez, Chisholm.

To be clear: Miles Davis And The Search For The Sound is a wonderful book that is astonishing to look at. Chisholm takes all the stops, pulls them out, and launches them into the sun. The way he shifts style and color and tone to reflect era and music in this biographical work is astonishing to me. This was a wonderful experience.

3rd Voice

by Evan Dahm

350+ pages

Self-published

Read at (rice-boy.com)

Evan Dahm's new big project after the close of Vattu is expansive and perhaps displays more invention and curiosity about the nature of peoples and cultures than anything we seen from him so far, which says a lot about the fabric of this new world and its characters and narrative. It's still early on (that is to say, 350 pages) in what looks to be a very large story.

3rd Voice is about the world that limps along for a bit after the end of the world on its way to becoming something else. A new world, perhaps. With any luck. While entirely alien to our own world and our sense of it, Dahm's new creation does share some thematic kin to what we find in, say, Canticles Of Liebowitz. It is, of course, actually quite different, but there are vibes and rhythms that I think fit well enough with Miller's own vision of a world crawling onward from calamity. Gods. Demigods. Priests. People. Many have fallen and a few get up.

I don't know where Dahm is going with this one, but it's definitely his most mature work as a creator.

[Dahm also fills the work with these metetextual editor's notes, which are just a wonderful touch—see last image in the samples above.]

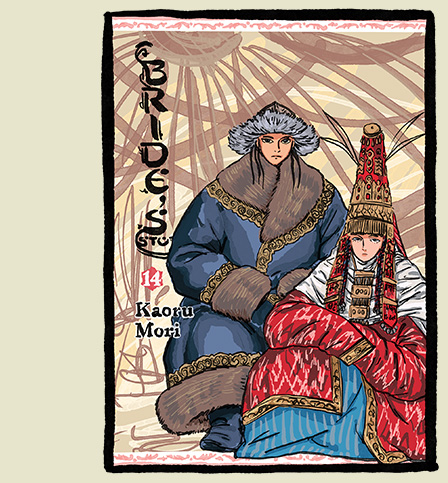

A Bride's Story

by Kaoru Mori

11 vols

Published by Yen Press

ISBN: 0316180998 (Amazon)

80 pages of horses. People hate drawing horses but Mori draws page after page after page, not just of a horse but of a murder of them. Just bucketfuls of horses. And then of course riders wearing their standard (for Mori) decorative attire. How she still has wrists that aren't continually smoldering is beyond me. (I mean, maybe they are. I haven't seen her wrists in years.)

Storywise, we're gathering steam toward the conflict that's been a growing shadow over the whole series: the Great Game-era collision of Russia into the Near East on its way toward occupying India and creating a wall against the British. The nomadic Steppe tribes (e.g. Amir's brother) are contemplating alliances with the city-dwellers (e.g Karluk and his people) to hold a footing against the coming Russian wave. I don't really have a lot of cheery thoughts about how this is going to pan out. Maybe Amir and Karluk will escape to Britain—though that's a pretty grim future.

And of course, since this is A Bride's Story, we need Moar Weddings!!! We get three, all rewards for a competition, where the winners get to choose their wives from those available. It's actually pretty sweet and heart-warming to see how it works out. Mori has a way of showing various courtship and marriage traditions that bristle against our sensibilities and show the happier outcomes for main characters while acknowledging the failed results of those same traditions for many others. Lots of maltreated women fill the background (in this volume, one woman whose husband burned half her face off).

The only problem with these is that I want the next vol immediately—and of course it won't arrive for another year.

Macbeth

by K. Briggs (adapting Shakespeare)

180 pages

Published by Avery Hill

ISBN: 1910395730 (Amazon)

Briggs's work on Macbeth here is astonishing. I can't speak to it as an adaptation because Macbeth is one of the Shakespearean plays I haven't read or seen performed. At least not in full. I have seen Throne Of Blood and read Ian Lendler and Zack Giallongo's Stratford Zoo adaptation, but these hardly grant even the whiff of authority on the question of adaptation. What I will say, however, and with some authority: K. Briggs's Macbeth is an astonishing comic.

And I think we can agree that is the important thing.

So remember how deftly Adam Hines leveled the use of collage and multimedia in Duncan The Wonder Dog? And how gorgeously Andrea Wulf and Lillian Melcher accomplished the same in The Adventures of Alexander Von Humboldt? Briggs joins them in pushing at the seams of comics-making, expanding the perimeter of the tent. This is a blistering use of color and imagery, making a performance of the page and an explosion of the stage. I don't think I've quite seen anything like this before. Hints in Duncan and Humboldt, but nothing quite to match Briggs's vision.

Blood Of The Virgin

by Sammy Harkham

296 pages

Published by Pantheon

ISBN: 059331669X (Amazon)

Blood Of The Virgin is a solid book meandering about the lives and turmoils (many self-inflicted!) of a young man (and his wife!) and injects itself into his ambitions and destructions in the '70s L.A. grindhouse production scene. I don't know how much research Harkham did for this thing but it feels like the real deal, based on how vibes and L.A. details sit with what I have read, seen, and remember of the era. (Perfectly, the one color section only shows blue skies out in the desert and out at sea but never in L.A., which didn't see a non-muck-colored sky between California's industrialization and the establishment of the EPA in the '90s.)

This is one of those books where everybody is a mess, just non-stop wagonfuls of neuroses, avarice, envy, drug-fueled horndoggedness, and a general selfishness that suffuses the daily gauze through which they perceive the world. And yet! And yet there are moments of human connection that do shine through, moments where the bodies riddled with burdens are sloughed off and the souls dance freely, cavorting with thoughts of wonder, dreams of beauty. Humanity, in Blood Of The Virgin, is down but perhaps not for the count.

Stand Still Stay Silent

by Minna Sundberg

4 vols

Published by Hivemill

Purchase from (Hivemill)

Stand Still Stay Silent is a strange fit here, since I'd read it before in webcomic form. Yet because the experience of reading it in a physical book is so different, I'm allowing myself the pleasure of recommending the book again.

The fourth and final volume of the first series was released in 2023, bringing to a close my collection of Stand Still Stay Silent. (The second series trailed off listlessly, so I won't be collecting it, pretty as it is.) Volume 4 is part catharsis and part closure and part climax. After the big feelings of vol 3, some subdued brooding and run-run-running make for good pace-setters. There's a deep well of sadness that subsumes the volume (with good reason) but there's also a moment or two of fist-pumping adulation.

There's also maybe the coolest Christian pastor in comics, written by Sundberg intentionally as a female pastor to piss of Christians (who were a bother to her at the time, several years before her eventual conversion)—ironically, this stalwart old woman is a favorite among all the Christians I know who've read the series, and Sundberg gives her one of the series biggest moments.

Reynard's Tale

by Ben Hatke

80 pages

Published by First Second

ISBN: 1250857910 (Amazon)

Both Ben Hatke and I share a hope that adult picture books might become a more common thing to find in homes, in hand, in hearts, on nightstands, on minds, and on bookshelves. My interest in picture books intended for grown readers harks back to the work of Shaun Tan (The Lost Thing, The Red Tree) at the turn of the millennium and more recently from Simon Stålenhag (Tales From The Loop, Electric State). And I suppose to lesser degree, the picture books of Neil Gaiman (The Wolves In The Walls), which are dressed as children's picture books but seem more intended to appeal to those children's parents.

With Reynard's Tale, Hatke proposes an "adventure" of curious mysteries, morbid fascinations, grim tidings, and uncanny reaches—all featuring his envisioning of the famous trickster fox. Hatke's always shown an affection for the roguish archetype, the rascal, the scalawag, the mischievous dodger who plays for self-interest but can't help hiding a pocketful of virtue behind a wink and a trick.

While I and my family have adored Hatke's books aimed at more youthful quarters (esp the Zita/Jack hexology), I've been waiting for him to begin producing work geared toward me. I'm selfish, apparently, and I have been rewarded for that because Reynard's Tale is lovely.

Salt Magic

by Hope Larson and Rebecca Mock

240 pages

Published by Margaret Fergeson

ISBN: 0823450503 (Amazon)

Ugh, the youth market demographic for graphic novels is both boon and blight. Neat that kids get to find stuff great for them, but it absolutely sucks that it was blind luck that I found Salt Magic, one of the coolest adventure stories I've read in the last several years. It was hidden away in the children's shelves. I only found it because I needed to pick up They Called Us Enemy for a class and I saw Hope Larson spine right next to it. Go read Salt Magic, guys. Go read it.

Portrait Of A Drunk

by y Jérôme Mulot & Florent Ruppert and Olivier Schrauwen (translated by Jenna Allen)

184 pages

Published by Fantagraphics

ISBN: 1683962893 (Amazon)

Portrait Of A Drunk is absolutely inconsequential, a ribald frolic that follows a very drunk man through a ludicrous pile of serendipities across which he remains unruffled, unfazed, and unconcerned by the terrors he perpetrates on his fellow humans on the quest to a) drink more and b) do whatever the hell he wants. He moves from depravity to depravity, killing and thieving, in a bafflingly liquid manner, such that his sojourn through a world spawned of mere mortals shackled by the constraints of something/anything resembling a social order becomes a gleefully rollicking adventure. How is this terrible little scamp going to wrong the world next—and without consequence to himself! And then what now? The ghosts of his victims and acquaintances (and so victims) are looking in on him from beyond the veil, baffled by his continued liberty, and wait, maybe this isn't as incosequential as I'd said? Maybe this is bookclub worthy? But no, it couldn't be. It's too fun a book to try to tease out wider meaning, isn't it? I guess we'll discuss that question at bookclub next month.

Petrichor

by Gareth A Hopkins

16 pages

Self-published

Read at (Hopkins's website)

"I wasn't expecting grief to be this much and I still don't know if I've earned it."

Hopkins' stories often feel like mood more than narrative. The words generally tell some sort of story in a poetic sort of way, but the accompanying images are abstractions that tighten and breathe at appropriate points to push feeling to the fore.

Petrichor is about grief and about life and about not thinking about it at all and about being consumed. It's about the first day of a holiday and all the promises and avoidances and opportunities to breathe that such a thing affords.

SupportProse I ReadNavel Gazing

Kill My Mother | Cousin Joseph | The Ghost Script

by Jules Feiffer

3 vols

Published by Liveright

ISBN: 0871403145 (Amazon)

Of all the crime graphic novels I've read, this is my №2, coming in a notch below Stray Bullets. It's wild and tangled and frisky—and until 2023, I'd only ever read the first two vols.

- Kill My Mother: The trilogy bounces back and forth between 1931 and 1952, but begins in 1933 with teenaged Annie Hannigan up to no good and wishing her mother were dead. Elsie Hannigan is working for Sam Hannigan's ex-partner, PI Neil Hammond, investigating (supposedly) Sam's murder. There's seamuses, boxers, three tall blondes, and then the war, and Hollywood, and USO nonsense, and plots and vengeance and betrayal and surprises.

- Cousin Joseph jumps us back to 1931 so we can watch Sam die and see what led to that moment. Unions, union busting, Red squads, Hollywood, fear of Jews, and the question of who is American and what is America govern the turns here.

- The Ghost Script wraps everything up in 1952. We see what's become of those who survived Kill My Mother and some of those introduced in Cousin Joseph. Lots of tangled ends tied up as Feiffer does a HUAC story and we get to see how awful the good old days were.

Part of what's so interesting about the series is that Feiffer coincided with much of this. He would have been 23 at the time of The Ghost Script. Gives everything a taste of verisimilitude, even if everything's a bit pulped up.

The most curious thing about the series is the finale's finale, which makes the end of Asterios Polyp seems mundane and expected.

If I were to say something negative about the books, it would be that Feiffer seems to hail a bit from the Winsor McKay school of lettering: it's a bit jumbled and bumps all over itself. (Paneling is a bit kazoo as well and it can be tough to figure out at a glance the order to read things.) But that's a quibble and pairs well with a big positive—charm of Feiffer's work here. It's a wordy wordy book for sure, but that's owed largely to it emulating the rapid-fire back-and-forth dialogue that finds its home in the films and radioplays of the era, like The Third Man radio broadcast, where characters speak all bunched up and jumbling all over each other.

Nathan Hale's Hazardous Tales: Above The Trenches

by Nathan Hale

128 pages

Published by Harry N. Abrams

ISBN: 1419749528 (Amazon)

I think this 14th Nathan Hale book, Above The Trenches, might be his best since Treaties Trenches Mud And Blood, which was the 4th book. It returns to WWI (only this time focusing on the dogfighters and arial combat) aaaand returns to the conceit of modeling people after their national animals. The French are chickens and the US are bunnies (explained in vol 4), so when we get an French-born American, he's a chicken with bunny ears. These two are the only NHHT books to do the animal thing, so it stands out in a helpful way.

Above The Trenches is very funny, tells some good stories, gives readers a hint to the horror of the war. It's great chaser to the earlier book with lots of small callbacks. Also, highly recommend Now Let Me Fly (see below at spot 33) as a companion graphic novel fleshing out Eugene Bullard's story, which gets brief mention at the end since Bullard entered the air service a bit after the main narrative closes.

Barking

by Lucy Sullivan

124 pages

Published by Avery Hill

ISBN: 1910395765 (Amazon)

Barking is wild. It's a skittering, scratchering ride along with a mind in mental distress, a woman institutionalized for acting out of an overflowing well of grief. Much like to the mind depicted, things to the reader will only make a scattered bit of sense. It's an uncomfortable read, an uncomfortable experience, and so it does its job pretty well.

Bea Wolf

by Zach Weinersmith and Boulet

208 pages

Published by First Second

ISBN: 1250776295 (Amazon)

Bea Wolf absolutely nails the cadence and alliteration of Beowulf while simultaneously adapting it to a whole new mise en scène. I'm not sure who the intended audience for the book is (I don't see kids taking to it), but I'm pretty sure every last Beowulf fan will love it.

I highly recommend reading it aloud so your mouth can sink into the suptuously delicious sonata of wordstuff. Beautiful wok by Weinersmith and fantastic illustrations by Boulet.

Flash Gordon

by Dan Schkade

Published by Comics Kingdom

Read at (Comics Kingdom)

Schkade took over the daily serial near the end of October, and his run has so far been pretty effervescent. Crisp, cartoony art with vibrant characters and fun plots.

And now I couldn't imagine it ever happening, but Schkade's new run on Flash Gordon (a story whose Queen-propelled movie satisfied every Flash Gordon Need that I thought I'd ever have) pushed me to get a subscription to a daily strip website just so I can hit the archives and luxuriate in the whole thing. That is, I think, a recommendation and a half.

Emanon

by Shinji Kaijo and Kenji Tsurata (translated by Dana Lewis, lettered by Susie Lee)

4 vols

Published by Dark Horse

ISBN: 1506709818 (Amazon)

With the new release of vol 4, I reread the series since my memory of what had happened previously had ended with vol 2. Still very well worth my time. Emanon remains one of those books where you come for the art but get smacked around by how ingenious the story is conceptually. It's a smart story and doesn't usually feel the need to hold your hand.

These stories jump around a bit between time periods. 1967, 1973, 1988, 1994, sometimes far in the future, etc. Sometimes you're here, sometimes you're there, and not necessarily in chronological order. It's pretty fun. We start out in vol 1 discovering that Emanon possesses an eternal consciousness that goes back to the dawn of life, that when she gives birth, all her memories transfer into the new child, leaving her former carrier rather a husk. In vol 2, we meet her friend, a time traveler, and discover the one time she had a twin brother. In vol 3, she loses her memory from an illness and we get to see what that's like for her. And in vol 4, we get to spend time with her as a child before she again turns to wandering, and we see her meet another strange person who believes himself the next stage of human evolution. It's all perfectly wonderful, and Tsuruta's adaptation of Kajio's stories are a real feather in the cap for comics. The series wants to be continued, but it's anyone's guess whether Tsuruta will do more. More Emanon and more Wandering Island. The only things I want more is more

Welcome To The Ballroom

by Tome Takeuchi (translated by Karen McGillicuddy, lettered by Brndn Blakeslee)

192 pages

Published by Kodansha

ISBN: 1632363763 (Amazon)

Apart from the stellar, dynamic art, Welcome To The Ballroom is such an interesting sports story because while it does follow the common track of a preternaturally talented youngster who's arrived late to the sport, his gains are more amorphous and much of his success and serendipity rests on the great skill of those surrounding him.

Fujita does have a special gift of being attenuated to the bodies of others, which gives him a boost, but he's untrained, unpracticed, and swamped with insecurities. He has some early moderate successes but by the end of vol 4 he sees a tape of one of his performances and realizes he's been carried by the women he's so far partnered with. The experienced dancers around him see a special spark there but seeing it actually ignite is still a long way off.

It's nice to see a sports protag really struggle.

Vols 5-10 nearly completes the second arc of the series, with Fujita and new partner Hiyama completely mismatched until it all clicks at the end. Lots of psychological stuff, lots of bickering. It all reads smoothly now that it's been collected, but stretching it out over years felt really really long—so I was glad to return to the series and read this arc all in a single debauched sitting.

I'm glad Takeuchi is back, hopefully in wonderful health, and I look forward to seeing her takes on Hot People Sweating: The Manga. Alternate localized title that you're probably more familiar with: Welcome To The Ballroom.

I will forever love Takeuchi for this, for taking people dressed all fancy and nice and then making them sweat rivers—because that's what happens in strenuous exercise. (I had a number of professional ballet dancer friends and so would see lots of Instagram shots and videos from practice, and maybe 10% of those *didn't* feature pools of sweat under armpit and sternum.)

This is probably a goodly-sized chunk of why superhero art never looks viable—all these people fightin' and jumpin' and sprintin' and swingin' and none of them ever look like they just walked under a sprinkler. Like, you can't tell me you were exerting yourself if you don't look like a wet dog.

Anyway, props to Takeuchi for finding the secret key to my heart, I guess.

Dead Dead Demon's DeDeDeDe Destruction

by Inio Asano (translated by John Werry, lettered by Annaliese "Ace" Christman)

12 vols

Published by Viz

ISBN: 142159935X (Amazon)

In Asano's Dead Dead Demon's Dededede Destruction, he retains the wild cynicism that you'll readily find in his other works but spices it up with some lunatic humor. This is a book about catastrophic alien invasion and how, for the average citizen, that'd merely just be a minor hassle to ignore while continuing to work our ultimately meaningless jobs. It begins as a funny book (and one gorgeously drawn) with Asano continually poking at the bear of contemporary society and its values, but as revelations and reality pile up, it grounds its zaniness in sober reflections and grim consequences.

If you found Goodnight Punpun too brutal (and, I mean, fair point) but still want to take part in the Asano conversation, Dead Dead Demon's is probably your entry point.

I reread 11 in order to get set for 12. 11 is the big climax, the countdown that the book's been announcing since vol 1. And it didn't disappoint, not for me. It's like combining Otomo's abiltiy to draw grand destruction with Asano's own ability to manipulate and draw over digital and photographic assets—and it comes off real well.

Vol 12 is kind of grim denouement and tying off a bow. While Asano is clearly still cynical toward the human condition and the societies it's built, he gives us one of the most upbeat wrap-ups since What A Wonderful World or Solanin.

Dead Dead Demons was entirely creative and may be my favourite Asano. It's definitely his funniest and probably the one I'll most readily return to.

Glaeolia

by tons of creators

3 vols

Published by Glacier Bay

Purchase from (Glacier Bay)

Glaeolia is a North American anthology of Japanese indie comics creators, a smorgasbord of stylists who help us scoff at the idea that all manga looks the same. While I'd read vol 2 last year, this year I got to jump into vol 1 and 3, and they are filled with delightful stories. Not every story landed well for me. Not every creator won my heart. But this is one of the charms of an anthology. I used to fret, longing for the mythical collection whose every story was exactly what I wnated or needed, but now I'm finally coming (rather late) to the idea that even the stories that don't win me over add value to an anthology. After all, the largest reason to engage an anthology is to sample a taste of a cornucopia of offerings—to see what's out there. And maybe I'm ready for some of it and maybe I'm not ready for others of it and maybe I'm going to be made ready for something I wasn't ready for through the simple act of reading it anyway.

That's probably too much focus on the idea of stories that I didn't care for, which is the minority of what's in these books. We'll just say this: for space issues, I'm trying to keep my book collection (curated gradually over 40 years) to around 2000 graphic novel volumes, which means dumping books, even if I like them, if they don't participate well enough in my personal library—and I don't see myself letting go of Glaeolia probably ever.

Family Style

by Thien Pham

240 pages

Published by First Second

ISBN: 125080972X (Amazon)

Pham published most of this a year ago on his Instagram (much like Ben Hatke did with Reynard Tale) and I really appreciated Pham's work. He'd appeared to level up since Sumo and Level Up, and the work is chunky and cartoony and beautiful.

Family Style is memoir and details via meals Pham's early memories of his family's escape from Vietnam, life in a refugee camp, and then his first years in America as a comics and movie and videogame loving '80s kid. Each chapter focuses on a food that Pham associates with that period, whether some food his mom saved for him on the refugee boat, the apple he associated with the first words he learned in English, the DQ burger he eats instead of the Vietnamese meal his mom made for him, etc. Pham adds in a final chapter not included in his Instagram version, a present-day chapter in which he is inspired to after 35+ years in the US finally seek citizenship (with the helpful badgering of the cartoonist friends fans will recognize, e.g. Lark Pien, Gene Luen Yang, and Briana Loewinsohn).

I loved this book. It was cozy and warm and showed the care of Pham's parents through years and years of hard times.

SupportProse I ReadNavel Gazing

The Mysteries

by Bill Watterson and Jon Kascht

72 pages

Published by Andrews McMeel

ISBN: 1524884944 (Amazon)

Part of a growing (I hope) recent development of picture books for adults. (Picture books are a mode of comics, or perhaps vice versa.) It's hard not to compare these recent projects against each other, and by the comparison, for as good as it is, The Mysteries seems the weakest of the crop. Electric State, The Envious Siblings, and Reynard's Tale!

Each of these are each vibrant in their own genres, and while Kascht's illustrations in The Mysteries are gorgeous and the main attraction, Watterson's story reads as a bit trite. It's a moral-lesson kind of book, much like the widest collection of contemporary children's books, allergic to wonder for the sake of it, needing to exist as pedagogy. And to be certain, The Mysteries does employ wonder and does celebrate wonder—but only does so as a cudgel in the argument proposed.

I liked The Mysteries but I didn't love The Mysteries—and I think the large part of it is that it reminded me of every adult who's confided to me that "I've got a great idea for a children's book," and it's always some idea about the lesson to be imparted rather than a kick-ass idea for something that would be great to read.

I will say that my greatest enjoyment was reading this with my 6yo and having him exclaim "Wait, what!" with every page turn in the book's final quarter.

I suppose I'll clarify that The Mysteries doesn't botch its moral. As well, the moral is fine: mainly that there are wonders and mysteries in the world and we may fear them and then attempt to explain them, but ultimately they remain and remain aloof.

March Comes In Like A Lion

by Chica Umino

4+ vols

Published by Denpa

ISBN: 1634428129 (Amazon)

With a few more volumes under its belt I'm sure the book will rocket to the top of my favorites much as the television adaptation did. It's just getting warmed up!

Now Let Me Fly

by Ronald Wimberly and Brahm Revel

336 pages

Published by PUBLISHER

ISBN: 1626728526 (Amazon)

Really well done tale of Eugene Bullard's eraly life, from fleeing the South in 1908 at age 13 and stowing away to Liverpool to becoming a boxer to finding himself happy and well-treated finally in France to fighting to distinction with the Foreign Legion in the trenches of WWI to becoming the first black fighter pilot ("The Black Swallow of Death") on a bet. The framing device has 64yo Bullard working as an elevator operator in Rockefeller Center and telling his story to ad exec Jon Casey while they're stuck in an elevator. It works and we are primed to wonder how this world-gallivanting, well-decorated hero could be reduced to pulling a handle for people who (largely) despise him—and we remain primed because there remain 40 years between the framing device and the story where Bullard leaves it, demanding a follow-up book. A book which I would defintiely read. I will say that having read Wimberly's LAAB, I was expecting this to be more, I guess, subversive, but it really does play pretty straight with only occasional wry glances to punctuate the state of things between blacks and whites (I'm guessing First Second wants it in highschools).

Vinland Saga

by by Makoto Yukimura (translated by Stephen Paul, lettered by Scott O. Brown)

13+ vols

Published by Kodansha

ISBN: 1646519787 (Amazon)

With the Baltic Sea arc in the past, Yukimura brings Thorfinn, finally, to the Vinland promised since vol 1. It's been a long journey and we'll play through one big final act, but things are shaping up for a solid conclusion.

This is a good middle chapter in the saga, bridging larger portions and putting the pieces into their places. We're introduced to the Mi'kmaq/Lnu people and we see seeds for Thorfinn's success and failure laid out. (Those rats are almost certainly going to play a role.)

Oh and also, the volume ends on a brilliant note, something I didn't realize I was waiting for until it happened and it felt as if I were finally taking a breath.

The Hard Switch

by Owen D. Pomery

100 pages

Published by Avery Hill

ISBN: 1910395706 (Amazon)

In the far-off future, "The Hard Switch" is the term used to describe the anticipated moment when the resource used to power actually reliable interstellar jump technology is finally and forever used up, stranding everyone wherever they are in the galaxy. The Hard Switch is a small story in a large setting, following a scavenging crew of three (or four if we include a small sad fish) who seek out old wrecks and try to syphon out their gas tanks Road Warrior-style.

The story in nice, the dialogue solid, and the world is well-built, but of course the truest joy is Pomery's art. Readers of Victory Point will be aware of how his strengths bend toward the architectural, and that's on display again here. Starships, pawn shops, docking stations, outposts. All are drawn meticulously. I don't really consider myself much of a sci-fi aficionado (I'll read it, but usually only if it comes specifically recommended), but by the end I wanted to see more of this world/universe he's cooked up.

Dogsred

by Satorou Noda (translation by John Werry, lettering by Steve Dutro)

2+ vols

Published by Viz

I'd heard Satorou (Golden Kamuy) Noda's new comic was up on the Shonen Jump app, which I got so my daughter could read all her Haikyu, Demon Slayer, and One Piece stories, so I popped over to check it out. It's fantastic. It's a sports manga, so if you've read or watched a couple, you know the general terms of the contract, but Noda is so much better and funnier than most cartoonists doing this stuff that Dogsred really sings. I was hooting out laughs, causing my children to ask what was up ("Nothing! Comics! Let me read!").

Storywise, it's about a genius figure-skater and Olympic hopeful who has a freakout and quits figure skating in a tantrum brought on by stress because mom recently died in an accident when she was driving him to practice and fell asleep at the wheel because she'd been over-doing it for his figure-skating career. Yeah, it's a lot.

Anyway, he and his sister (who got forced out of figure-skating bc his mom only had time/energy to support one of them) move to Hokaido (familiar to Golden Kamuy fans) to live with his grandpa, to a land where hockey is king. Pretty soon, skater lad is into ice hockey and that's two vols.

What I've left out is everything that makes the book great, which is the comic timing and most especially Noda's cartooning. His expressions are incredible. I hate reading comics digitally, but I'll come out for this.

Darkly She Goes

by Hubert and Vincent Mallié (colored by Bruno Tatti, translated by L. Benson)

160 pages

Published by NBM

ISBN: 1681123134 (Amazon)

Beautifully illustrated, Darkly She Goes tells the story of a curse and the myriad smaller curses that naturally spin out from the larger curse. It's a romance between broken people, one in which the lovers are pawns in a vindictive divorce, and what hope is there for love in such a game, in such a combat?

Akane-Banashi

by Yuki Suenaga and Takamasa Moue (translated by Stephen Paul, lettered by Snir Aharon)

3+ vols

Published by Viz

ISBN: 1974736482 (Amazon)

What a righteous story. I went in as an interested skeptic but quickly swapped over to an affectionate reader and have swapped personas once again now to anticipatory fan. This is my trajectory with all the best shonen-y sports manga/anime I've ended up loving—e.g. March Comes In Like A Lion, Chihayafuru, and Run Like The Wind/p>

It's pretty much a perfect ride through all the rhythms of a shonen sports drama with a bit of the political intrigues of Eagle: The Making Of An Asian-American President for good measure.

Akane-Banashi is at its best for me when it's developed its side characters well enough and with enough sympathy that I root for them to beat Akane in competition. March Comes In Like A Lion and Chihayafuru both excel at this as well.

The major difficulty Akane-Banashi faces is the same encountered in music-forward books like Blue Giant: it's trying to portray a performance that is absolutely dependent on the heard aspect, on the auditory rhythm of the storyteller. It's the reason I've declined reading Showa Genroku Rakugo Shinju—t's just so much more fulfilling to watch the show and get to see/hear the intricacies of the performance that are impossible to get through a mere comics page. Recognizing the struggle, Akane-Banashi works hard to emphasize other interests and makes particular use of pushing the telling of stories to reflect, react to, and comment on the exterior narrative—usually to decent effect.

The book is a lot of fun (fun enough that I read all ten available volumes in 2 days) and I'm probably completely onboard for the rest of the story. Lots of drama to eat up. I'd say it struggles in its early volumes to overcome its shonen topos but once the expected vectors have been established or addressed, Akane-Banashi allows itself to flourish. I'd say this growth transition takes about four volumes to land.

Also, whatever the case, reading Akane-Banashi really does is make me want to watch Showa Genroku Rakugo Shinju again. Because, man, that's all-time television.

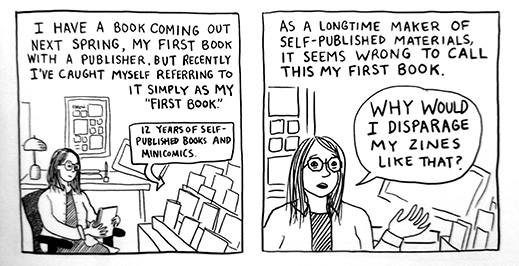

Self-Publishing In Third Space

by Caitlin Cass

16 pages

Self-published

Read comics like this by subscribing to Cass's (Postal Constituent)

Cass's new 16-pager about self-publishing and legitimacy opens with a banger two panels.

She then goes into a bit ot the history of zines and self-publishing and the perceived role of publishers as legitimizers. It's such an easy lie to slip into too—the idea that a publisher legitimizes. (Also, I own 2 of Cass's other books, each over 200 pages), so that further highlights the lie of "legitimacy.") Self-Publishing In Third Space is a nice brief rumination on the benefits of self-publishing in terms of community, even if increasingly people are viewing it as a stepping stone into a "legitimate" publisher's line of sight.

As a self-publishing comic creator myself, I found a lot of resonance with Cass's expressions of love, doubt, and frustration here.

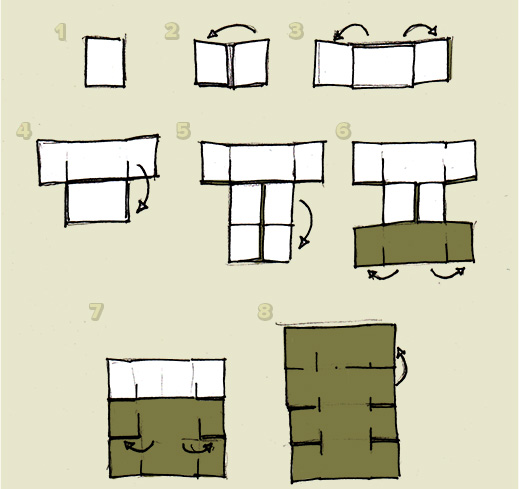

I've followed Cass work not since the beginning but since meeting her at SPX in 2013. It's always very different and very personal. For a while, she was hand printing with a screen press. There is no common size for her work and when I get one of her packages in the mail every couple months, I never know what I'm in for. Maybe a tiny comic, maybe a comic that folds out into a poster, maybe something that is read weirdly like this:

I'm excited for her to be putting a book out through Fantagraphics (tho I know Fanta pretty much only markets and supports its all-star creators) not because it means Cass had finally made it but because it'll be easier (for a short time at least) to recommend her work and know people will have an easy time finding it, say, through Amazon.

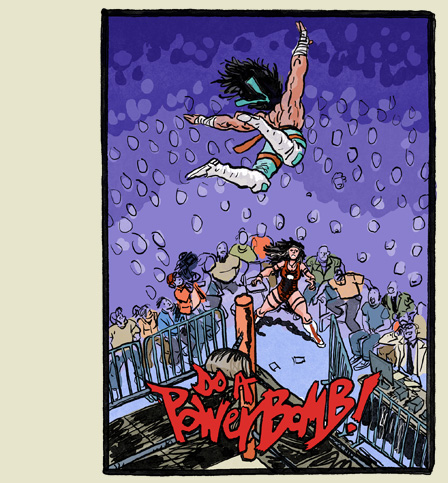

Do A Powerbomb

by Daniel Warren Johnson (colored by Mike Spicer, lettered by Rus Wooten)

168 pages

Published by Image

ISBN: 1534324747 (Amazon)

I was in seventh grade in 1987. I was perhaps the perfect age for becoming desperately fanatical over the events leading up to Wrestlemania III. It was the perfect combination of soap opera and athleticism. My brother and I would watch WWF matches every Saturday morning. I would come to school the next week and exuberate over what happened, what would happen next, who were good guys, who were bad guys, and who would win the championships. Hulk Hogan, Nikolai Volkoff, George the Animal Steele, Adrian Adonis, the Honky Tonk Man, Billy Jack Haynes, the Junkyard Dog, the Iron Sheik, Hillbilly Jim, Captain Lou Albano, the British Bulldogs, Ricky the Dragon Steamboat, Kamala the Ugandan Headhunter, the Rougeau Brothers, Jake the Snake Roberts, Macho Man Randy Savage. And Andre the Giant. These men were the lords on the earth. They were tremendous figures—though their feuds often seemed concocted even to a seventh-grade me.

In March of 1987, Wrestlemania III took place in the Pontiac Silverdome to, apparently, record attendance. For whatever reason, my dad took the cue that we loved wrestling and got us tickets to watch on closed-circuit television along with a packed-out crowd at the Anaheim Convention Center (where they've held Wonder-Con this past decade). It was easily the most exciting thing I had experienced up to that point. We roared, we booed, we screamed. The hall was electric with fans who were deeply invested in the stuff. I, personally, was there for the Ricky the Dragon Steamboat vs Macho Man Randy Savage grudge match. I was furious with Savage and needed to see vindication for the injustices he'd earlier perpetrated against Steamboat. And honestly, it was the best wrestling I'd ever seen.

And then I promptly lost all interest in professional wrestling. I was satisfied. I had Savage vs Steamboat under my belt and needed nothing more from that world.

It's been almost 40 years and while Do A Powerbomb didn't reignite against my apathy for the sport, it did (like Kagan McLeod's Infinite Kung Fu) allow me to for the space of a volume suspend that apathy and allow me to enjoy some great art and dynamic moments. For a book about grief, it's actually pretty funny and seems to lead, ultimately, to a joke about Jacob wrestling God. Which, I mean, fair play.

SupportProse I ReadNavel Gazing

The Suit

by Gareth A. Hopkins

9 pages

Self-published

Read on (Hopkins's website)

Hopkins abstractly explores a man's discomfort and unfamiliarity with his body vs the act buying a suit in time for a presentation. The narrator's compounded failures to find a suit in the right size gradually depletes him while the art swirls and bubbles around, a turmoil.

A Smallness

by Hagai Palevsky and Steph C.

24 pages

Self-published

Read on (Palevsky's Bluesky)

I read this on Palevsky's Bluesky wall. A series of conversations against backdrops that while less abstract feel as much about mood as the art in Hopkins' stories. The art is of empty places, unnaturally empty places. A hotel lobby, a bus depot, a news room, a jumbo jet's cockpit. Only in the penultimate panel do we see a shadow of a human presence. Do I know what it means? I do not. Was it a nice comic? It was.

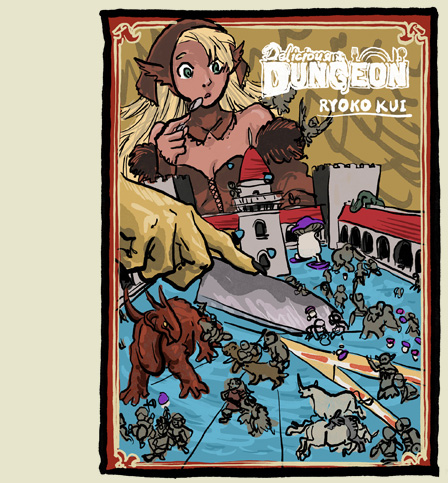

Delicious In Dungeon

by Ryoko Kui (translated by Taylor Engel, lettered by Abigail Blackman)

14 vols pages

Published by Yen Press

ISBN: 0316471852 (Amazon)

With two more vols to go, everything is wrapping up but taking its time to get there. The book is still good and we get these bits that confirm the characters that we loved from the start, making them more grounded and solid, but I still feel that this A+ book has maybe overstayed itself. My 12yo, however, disagrees and was heartbroken when I told him there'd only be two more volumes and that it was already finished in Japan.

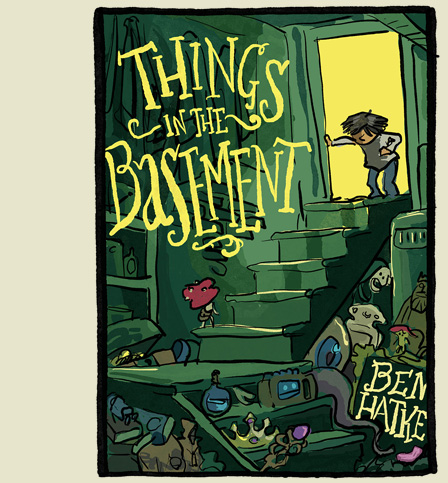

Things In The Basement

by Ben Hatke (colored by Zack Giallongo)

240 pages

Published by First Second

ISBN: 1250836611 (Amazon)

While this Piranesi-inspired book (inspired by the artist, not the novel) has the demographic label Young Reader Graphic Novel on it, I think it plays in more grown-up climbs as well. There's still certainly some childlike whimsy about it, but there are moments that are 100% talking to the grown-ups in the room. I read it myself and then to test it, I read it to my 3yo and 5yo, who both loved it. Colorwise, it's a very dark book (being set in a labyrinthine basement and all), so read it in good lighting.

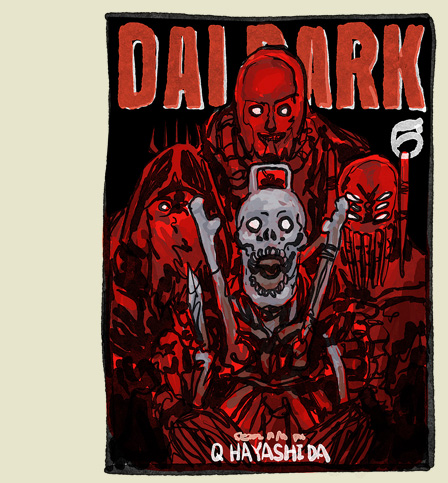

Dai Dark

by by Q Hayashida (translated by Daniel Komen, lettered by Phil Christie)

6+ vols

Published by Seven Seas

ISBN: 1648271162 (Amazon)

I struggle to know what to think about Dai Dark. I love reading it. I laugh a lot at its bizarro humor. But it just hasn't captured my affections in the same way the found-family dynamics of Dorohedoro did. It hardly seems fair to compare them, but when I go from one of my all-time favorite comics experience to a book that's merely fantastic, there's an unshakeable dissonace at play.

Volume 5 upped my involvement for sure, offering some connective tissue, but vol 6 kind of fell into the disconnected hijinks of earlier vols. For me at any rate.

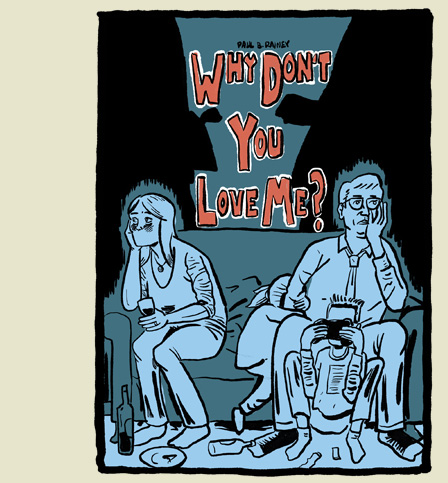

Why Don't You Love Me?

by Paul B. Rainey

224 pages

Published by Drawn & Quarterly

ISBN: 1770466312 (Amazon)

The mid-book twist (and consequential evolution) is probably what gets Why Don't You Love Me? on so many of the year-end lists but that comes after putting up with a lot of cynical humor for a long time. The strips are funny, but just like how you shouldn't just plow through a volume of Popeye, you shouldn't plow through 100 pages of Haha Parenthood/Being Married To You Sucks comics.

I actually laughed at a good chunk of these unhinged and rather absurdist domestic barbs. It's great humor. I just did the book a terrible disservice by trying to finish it over a couple of days (it's like when I thought I'd read the first vol of Pogo over the space of a week, which just smash-blurred everything into a Pogo soup). It would have been a primo experience to get a strip a day of Why Don't You Love Me in the newspaper if they still had those.

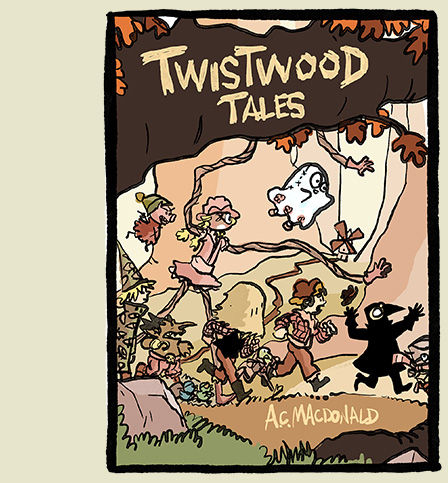

Twistwood Tales

by A.C. Macdonald

160 pages

Published by Andrews McMeel

ISBN: 1524877417 (Amazon)

Twistwood Tales is a pile of highly delightful strips that very often play off common (or formerly common?) proverbs. I say formerly common because I had to explain "throw the baby out with the bathwater" and "you are what you eat" to my 12yo because he'd never heard of these or a host of other bon mots Macdonald plays off. Bizarre, huh! Anyway, these strips firt feel like they are disconnected, like episodes of Larson's Far Side, but gradually you notice that you're skittering around a large tapestry and that there's a kind of continuity between strips. Someone who goes to the doctor on page 20 will show up 20 pages later showing the resultant "medical solution." Really helps to elevate the strips!

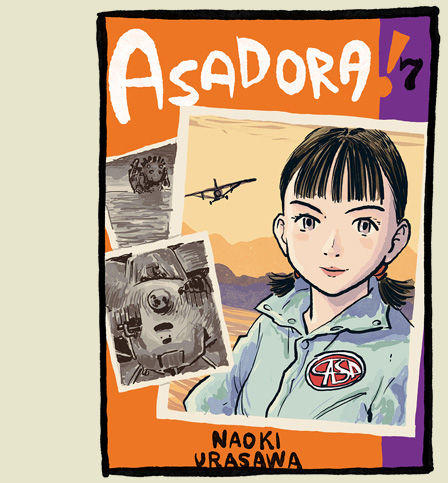

Asadora

by Naoki Urasawa (translated by John Werry, lettered by Steve Dutro)

7+ vols

Published by Viz

ISBN: 1974717461 (Amazon)

I reread all the available vols of Naoki Urasawa's version of Godzilla: Half-Century War this week and had a lot of fun. As always, Urasawa reads better as a binge. Only 5 years of the 61-year storyline have passed in-comic, getting us to 1964. Eventually, the story gets us to 2020, so we've got a ways to go. My kid finally realized the timeframe involved. "Wait, she's gonna be an old lady by the end!" and then "Wait! that means the old dude is gonna die!"

Vol 7, just released, is maybe the funniest yet. It begins with an even more forthright troll on Urasawa's part than the way he opened vol 2—though not as brilliant as that is-that-an-eggplant-in-the-sea-or-are-you-just-happy-to-see-me juxtaposition. My daughter hated the funniest part because it capitalizes on further humiliating loser infatuated-with-Asa runner kid Sho with Drugs. But I was hooting. It's nice to see Urasawa just being ridiculous.

Song Book

by Caitlin Cass

Self-published

Read comics like this by subscribing to Cass's (Postal Constituent)

This was super interesting, about the songbooks that helped unify the suffrage movement in the US in the early 20th century—and how even though they were this force that kept the community feeling like a community, they rarely represented the vision or context of the suffragettes. Also interesting was how the political strategy of suffrage shifted over time, as exemplified through the songs, from an egalitarian sort of feminism where women deserved the vote because they were the equal to men to emphasizing the difference between the sexes, often privileging the experience of well-off white women who were able to stay at home as delicate gentle homemakers rather than toiling in brute factories.

Frieren

by Kanehito Yamada and Tsukasa Abe (translated by Misa "Japanese Ammo," lettered Annaliese Christman)

10+ vols

Published by Viz

ISBN: 1974725766 (Amazon)

This feels like a cross between Delicious In Dungeon (picking up from the conversation there about age and racial lifespans) and To Your Eternity. It's about an impossibly old elf mage and how she gradually loses all her friends to their own mortal lifespans over and over. In that sense it's also like Bendis/Oeming's Powers except that the mage, Frieren, remembers everything. It starts out nice and breezy but the story is gradually building.

It's a fun series, different from a lot of what's out there. My only quibble is that it may be stretching itself out too long. It feels like it would have been a good 6-volume series, like Girls' Last Tour.

SupportProse I ReadNavel Gazing

Want to support me?

There are basically a couple ways to support me, if that's something that sounds fun or valuable to you.

1) Through buying my stuff (Etsy). It's mostly prints and posters right now, but you can also buy my children's graphic novel, Monkess The Homunculus.

2) There's no financial benefit for me, but if you want to check out my indie comics, you can read most of them in this Twitter thread here.

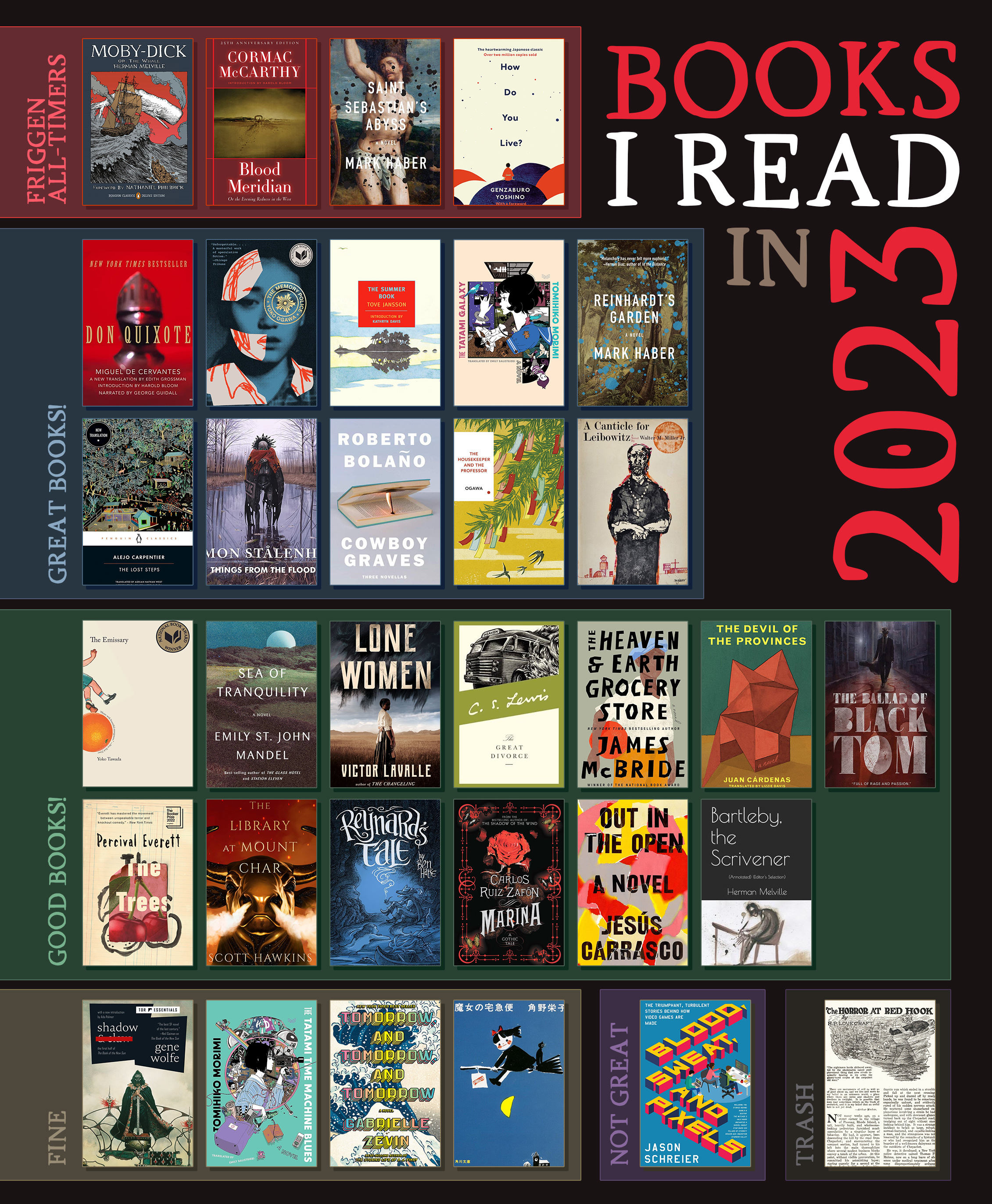

Prose I Read In 2023

I read 33 books in 2023. I'm better at picking out books these days so most were good or better, which is a nice way to live.

If you'd like my thoughts on each, they're catalogued in this Twitter thread here.

Navel Gazing

Coming up with a ranked list of things for a personal site or post on Facebook is entirely different in nature from ordering things for a Serious Critical Outlet (which I vaguely pretend to be). I can't just post What I Liked because 1) I have a site mission to consider and 2) for the list to be recognized as worthwhile to most readers, it has to contain enough of those things that other people would list to seem legit.

And while I never cheer on popular books that I hate just for the concept of earning legitimacy, there's always a bit of artificial list reorganization that is maybe even subconsciously designed to appeal to a readership. And maybe I'll even bump up a smallpress indie book that you can't even buy because Man that makes it feel like I'm serious about comics and you should trust me. (By the way, I *am* serious about comics and you definitely *should* trust me.) But maybe I won't do that. Most of these motivations are present but subconscious.

Does the fact that I'm on friendly terms with some creators give those books a bump? I don't see how it couldn't, even if I'm not conscious of it happening. When you read a good book by a stranger, you think, "Hey that was good!" When you read a good book by a friend, your naturally warm feeling for that other person blends with your experience of the book (because nothing social occurs in a vaccum) and now you think, "Man, that was a good book! I loved it!" And of course friendship also tends to soften criticism as well. Because we're not robots, you and I.

Also, I have to balance in some sort of subjective rubric for valuating a) What I liked with b) What is valuable and c) What is high in craft-quality. Every year, I find creating the list more daunting and more frustrating. Especially since not only is #26 not substantially "better" than #27 but also #26 is likely not substantially better than #45. I mean, it's a good problem to have. Lots of good books to read. And more every year. Essentially, we will never run out of good comics to read. It's like a golden age or something.

Good Ok Bad features reviews of comics, graphic novels, manga, et cetera using a rare and auspicious three-star rating system. Point systems are notoriously fiddly, so here it's been pared down to three simple possibilities:

3 Stars = Good

2 Stars = Ok

1 Star = Bad

I am Seth T. Hahne and these are my reviews.

Browse Reviews By

Other Features

- Best Books of the Year:

- Top 50 of 2024

- Top 50 of 2023

- Top 100 of 2020-22

- Top 75 of 2019

- Top 50 of 2018

- Top 75 of 2017

- Top 75 of 2016

- Top 75 of 2015

- Top 75 of 2014

- Top 35 of 2013

- Top 25 of 2012

- Top 10 of 2011

- Popular Sections:

- All-Time Top 500

- All the Boardgames I've Played

- All the Anime Series I've Seen

- All the Animated Films I've Seen

- Top 75 by Female Creators

- Kids Recommendations

- What I Read: A Reading Log

- Other Features:

- Bookclub Study Guides