Welcome to my annual attempt to share what I feel are the best comics of the previous year (in this case, the books of 2018). Before we get down to it, a caveat:

While past lists have been more robust, this year's is going to be a bit more trim, a top 50 instead of a top 100 or 75. I lost my job of 20 years last May and while I've picked up a little bit of freelance in the meantime, it hasn't been enough to cover bills let alone enough to indulge this pastime. So I've had to rely on the local libraries (and interlibrary loan) more than usual, which is fine, but makes it hard to keep up on the year's releases. Still, I was able to come up with 50 good books that I don't heditate to recommend.

Okay then, of course all the usual obnoxious caveats apply: a) that these lists are always only going to be a highly subjective record of tastes of a particular moment in a given segment of time; b) that it's virtually impossible and actually impossible to retain the same memory of a work read in January as it is of one read in November; c) that I of course haven't read a great many of the potentially fantastic works from across the year. All that's the same-ol' same-ol'.

Eligible for this list I'll be including:

- Comics printed in collected form for the first time in 2018

- Comics printed as books for the first time in 2018

- Comics printed as books for the first time in the US in 2018

- Comics published on the web in 2018

- Comics published through digital services like Crunchyroll in 2018

- Important comics reissued for the first time in many years

I believe that covers all my bases. Really though, I'm less interested in being a stickler for details than I am in just flat out recommending you some great comics reading from over the last year. So let's do that.

My Best 50 Comics of 2018

Berlin

by Jason Lutes

580 pages

Published by Drawn & Quarterly

ISBN: 1770463267 (Amazon)

Berlin readthrough tweet thread

Every now and again, a comic comes out that assures me that the medium can tell certain kinds of stories in a way that no other medium can touch. Every now and again, a comic comes out that despite its natural humility asserts itself as a model to which the medium should aspire. Every now and again, a comic comes out that just flat-out knocks me off my feet and makes me think that everything is going to be alright after all.

It’s not that Berlin presents such a rosie view of the panoply of human history. It doesn’t. It’s not that Berlin offers a solution to the din of political strife that will always wrack the tired bones of human society. It doesn’t. And it’s not even that Berlin allows true love to conquer even the dankest moments of our human despair. It can’t.

What Lutes’ book does, however, is demonstrate that creative geniuses still stalk the earth. His storytelling is virtuosic. And in addition to his mastery of the comic medium, Lutes proves himself an excellent student of the human state, capturing intricately the poisons that infects us all. Sure he depicts flawlessly the poor, huddled masses as they struggle to stave off starvation and fight for a political hope that will surely disappoint (as political hopes are wont to do), but further, he delivers too on the poisons that infect even human joy and celebration. We are given witness to ecstasy and abandon, but simultaneously, we also are allowed to see the darkness that threatens from the horizon, that in some sense has already crept into the lives of the happy.

And Lutes does this in such a way that he doesn’t come off as depressing so much as he does real. There is a veracity to his work that I cannot help but admire. As far as story direction, I didn’t like some of his choices for some of his characters. But they were always real choices. And I respect the story for it. And they set up well the story to come.

2018 capped for Berlin a 22-year journey. Those of us who'd been along for the ride might have been forgiven for wondering if Lutes would actually ever complete this masterpiece. Berlin came to us in a trickle, in dibs and dabs. Longer works have appeared in far less time (Tillie Walden's On A Sunbeam below , for instance), but these things take their own time (cf Duncan The Wonder Dog, vol 2) and there's so little money in literary comics that it's impossible to fault gradual creators. And at the end of the day: worth the wait.

On A Sunbeam

by Tillie Walden

544 pages

Published by First Second

ISBN: 1250178134 (Amazon)

Walden's story here is breath-takingly beautiful. Light and darkness play against gorgeous spacey vistas, presenting empty the threat of making too miniscule the human drama unfolding in the foreround—because, really, what can matter in the face of the cosmic? Walden's answer is grandiose: the mundane daily life of a girl. And to misappropriate Walter Simonson: it is answer enough.

Walden bounces aroung through space and time to build her characters' story, relationship, and world—in much a similar way to Evan Dahm with Vattu. Only her place and time cues are a bit more overt. It can be envigourating, the way Walden lets one story inform another and vice versa. And throughout, there's this sense of quiet danger, of foreboding. Everytime I read a new chapter, I'm nearly overcome by a creeping anxiety. Like THIS is the chapter where it all goes wrong. And of course it eventually does and oh what a blast that is.

And on top of all of it, we have Walden's illustrations. Stunning work. I'd included this on last year's Best Of list because it was released digitally, which was great. But now, reading it in my hands, the story has so much more solidity, that I felt it was worth revisitation.

Twists Of Fate

by Paco Roca (translated by Erica Mena)

328 pages

Published by Fantagraphics

ISBN: 1683961250 (Amazon)

I was a big fan of Paco Roca's earlier work Wrinkles, a look at one man's experience with Alzheimers. Knowing myself a fan still didn't prepare me for just how much I would enjoy Roca telling the story of La Nueve, a WWII combat unit composed principally of Spanish republicans and anarchists who'd fled Spain at the end of its civil war, hoping on the Allied promise of assistance in fenestrating fascism from Spain just as soon as Paris could get liberated. Hint: the Allies promptly forgot.

Through a series of interviews with a fictional conglomeration character, Roca (a character himself in the story) is able to tell us the story of these largely ignored men and their place in the bloody culmination of modernist history.

The illustrations are lovely and lively, the storytelling momentous and moving, and the history a tapestry of the human drive for freedom and destruction. Highly recommend.

Young Frances

by Hartley Lin

144 pages

Published by AdHouse

ISBN: 1935233424 (Amazon)

Young Frances is very good at what it does. It tells the story, principally, of Frances Scarland, who begins the series at the low rung of the law firm totem pole but gradually begins to climb, almost accidentally, through no ambition of her own. It's the story of her and her best friend Vickie (an actress) and the friends like Peter who enter their orbit. It's the story of pretty real feeling people living pretty real feeling lives. It's comfortable and enjoyable and relatable and pretty much perfect. I'm glad I'm on this train now. You should get aboard too. Choo choo.

Because I featured Pope Hats 5 on last years list, I wasn't sure I sure take up space on 2018's list with a collection from the series. But the point of this list has always been (rather than to rank these things) to celebrate what's great in comics and point you toward good reads that you *might* have missed. And as I sat reading Young Frances last week, I was reminded just how fantastic this series is.

The Golden Age

by Roxanne Moreil and Cyril Pedrosa (translated by )

234 pages

Published by Europe Comics (digital only til 2020)

Kindle edition: (Amazon)

Around July, Cyril Pedrosa's (and Roxanne Moreil's, but I don't know her work yet) new book was being released a chapter a week for free. The only catch was that you had to keep up because once chpater 2 was out, chapter 1 was no longer available. I ended up missing chapters, so I had to wait for a pay-to-read version. Unfortunately, the book won't hit print until summer 2020, but for the meantime, you can read it on Kindle or Comixology. I despise reading digitally, but I did it for this. And it's good. Great, even.

Pedrosa is able to create the most lush story environments and the most imaginative comics-telling frames. And for this story he created for himself a new method for colouring his work that you can see in practice here.

Upgrade Soul

by Ezra Clayton Daniels (lettered by DC Hopkins)

272 pages

Published by Lion Forge

ISBN: 1549302922 (Amazon)

I was put off for a long time from reading Upgrade Soul because of the cover, which evokes artsy fartsy indie comics mystique (like, real indie comics, the scary obtuse kind, not whatever crisply pacakaged competent stories Image and Dark House are putting out). I thought I was going to pick up this book and come away with something resembling a Feeling of what the creator might have been thinking about. Instead, Daniels delivers a fascinating sort of thriller that contemplates race and transhumanism and the ethics of living in the coming future. This was easily one of the most interesting books I read from 2018.

Stand Still Stay Silent

by Minna Sundberg

974 pages

Self-published

Read here

Sundberg in 2018 wrapped up what is now the first story in the Stand Still Stay Silent world. The big shocking moment came in 2017 with a moment of paramount peril and heartbreaking denouement, but 2018's wrap-up involved a beautiful and touching interaction with a long dead Danish pastor whose fidelity to her flock led to one of the best comics moments of the year. Looking forward to seeing where the second story takes us in 2019.

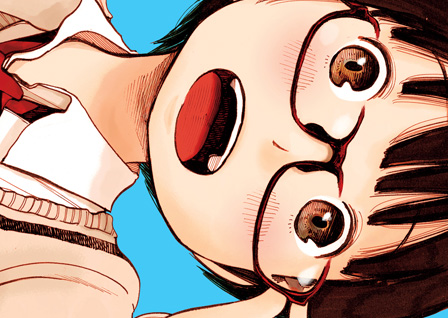

Dorohedoro

by Q Hayashida (translated by AltJapan Hiroko Yoda and Mat Alt, lettered by Kelle Han and James Gaubatz)

23 vols

Published by Viz

ISBN: 1421533634 (Amazon)

Dorohedoro readthrough tweet thread

Omigosh, Dorohedoro is so close to complete. It's already finished in Japan. We're just waiting for what I'm guessing is probably going to be July or so this year? Fingers crossed.

So yes. Now. Now is the time to get on the Dorohedoro train. You have 22 volumes to read before summer. It'll be worth it. Dorohedoro is one of those all-time books, one of those that turn the corner of the medium, offering something fresh and giving us all a taste of what could be if all creators were mad scientists. Also, they are somehow making an anime adaptation of this aned I don't even know how that could be remotely possible.

But what's so special about Dorohedoro? Beyond the ridiculously chaotic imagination Hayashida evidences in her world-building, beyond the revelry in grotesque body horror, beyond the wildly creative page layouts, beyond the humour that steadfastly refuses to allow the horror elements to overwhelm us, beyond the mystery and intrigue and thrills—beyond all that, Dorohedoro shows with so very much heart what it looks like to enjoy true camaraderie. Caiman and Nikaido, Shin and Noi, Fujita and Ebisu, the whole of En's family, Natsuki and the Cross-Eyes, everyone involved in Tanba's restaurant. All of these people have friends looking out for them, offering protection and loyalty and willing to pull out all kinds of stops for their welfare. Even the ends that crime-boss En will go to for his minions is pretty incredible.

I'm looking forward to seeing what Hayashida has for us at the end, but even if she screws up the conclusion as badly as Bone does, this book will still be one of the great canon treasures of the medium.

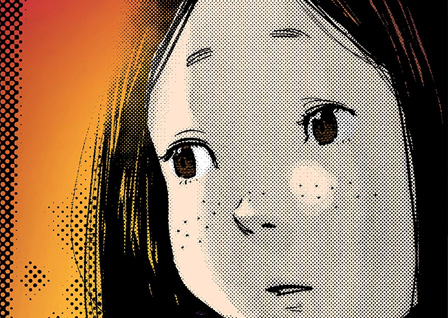

Dead Dead Demon's DeDeDeDe Destruction

by Inio Asano (translated by John Werry, lettered by Annaliese Christman)

4+ vols

Published by Viz

ISBN: 142159935X (Amazon)

Dead Dead Demon's readthrough tweet thread

Dead Dead Demon's is the most blatantly satirical work we've seen from Asano in the US. Diabolically eviscerating facets of the contemporary millieu, it presents clueless socialmedia heroes and pastiche culture warriors in a way that is simultaneously compassionate and callous. Asano invites the reader to wonder at the implications of their own small decisions and how they implicate us in the larger calamity of the Way The World Is. DDDddddD pits a hawkish lust for violence against the backdrop real violence and the society that permits and ignores it. I don't want to speak for Asano (his work will speak for itself), but my sense is that DDDddddD rightly pins us all as culpable in the tremendous number of failings in our societies.

I don't know if this is my favourite work of Asano's but it may be.

Monk!: Thelonious, Pannonica, and the Friendship Behind a Musical Revolution

by Youssef Daoudi

352 pages

Published by First Second

ISBN: 1626724342 (Amazon)

I'm not sure this is the case but it sure feels like all the best biographical comics come from continental Europe. Glenn Gould, A Life Off Tempo blew me away a couple years ago, and now Daoudi's Monk blows socks off in a different sort of way. Both get at their subjects via unconventional paths. Both are dreamlike and secure in their depictions. If you're looking for a treatment of one of America's greatest and most complicated composers, this book will be a treasure. Less a presentation of the details of Monk's life or of the technicalities involved in his methodology, Monk (the book) is more concerned with elucidating the vibe of Thelonius Sphere Monk. A worthy project and worthy book.

Ooku: The Inner Chambers

by Fumi Yoshinaga (translated by Akemi Wegmuller, lettered by Monalisa De Asis)

14+ vols

Published by Viz

ISBN: 1421527472 (Amazon)

Would highly recommend the series Ooku: The Inner Chamber. It's an alt-history of Japan. During the third shogunate (what, around 1625 or so?) the country gets swept with the red-face pox, a pox strain that Y-The-Last-Man-style only affects males. Only 20% of the male populace survives so society (and even the shogunate) switches to a female dominated life and governance.

The cool thing is that despite the switch, Japanese history is essentially unchanged. All the shoguns and all their stories and all the Japanese events remain unchanged save for that now it's women in the same roles. So you're getting this amazing story that is basically just a trick to get you to read Japanese feudal history and think about women outside their traditional roles. And it's amazing.

And there are some seriously deeply Machiavellian nuttos up in this thing. Poisonings are rampant. Scandals, beheadings, coups, maneuvering, jockeying heirs, the whole shebang. It's madness and you want so badly for some catharsis and for the villains to get theirs. And sometimes you get that but a lot of times the bad guys just win and never suffer a single consequence.

And the crazy thing? All of this really happened because Yoshinaga is just telling you the story of Japan.

Solanin: Epilogue

by Inio Asano (translated by Christine Dashiel, lettered by Brandon Hanvey)

48 pages

Published by Viz

Kindle edition: (Amazon)

After the dizzyingly dark vantage of Goodnight Punpun, the tragically broken lives of A Girl On The Shore, and the madcap cynicism of Dead Dead Demon's, it's neat to see Asano return to one of his more guileless works, and one that many find his most relatable. It's a kind of Before Sunrise/Before Sunset thing to circle round again on these characters after 10 years. It feels good and it feels right—and as Asano notes, it feels like the kinds of things Asano wouldn't have been able to say 10 years ago simply because a 25-year-old can't imagine how their perspectives will shift by age 35. (I'm 45 and am quite a different sort of person from who I was at 35. It happens.)

Girls' Last Tour

by Tsukumizu (translated by Amanda Haley, lettered by Abagail Blackman/Xian Michele Lee)

6 vols

Published by Yen Press

ISBN: 0316470627 (Amazon)

Girls' Last Tour readthrough tweet thread

Tsukumizu's GIRLS' LAST TOUR is a wonderful book. Cute, thoughtful, morbid, and filled with humanity. It's about two teenagers, Chito and Yuuri, who ride around the post-war ruins of civilization on their halftrack both trying to pass the time and trying to survive. The need food, water, shelter, and fuel, and as they putter around acquiring these, they chat about stuff. What music is, what god is, why people go to war, what's worthwhile, what cheese is. Stuff like that. They need each other and while they're very different in personality and interests and intelligence and ability, they are pretty much all they have. There're not really any other people around. One here, one there, but food is scarce and so is the will to keep living. One person they meet hasn't seen anyone in so long that he starts choking when he tries to use his voice.

Despite the brevity and abortive nature of the girls' forays into the philosophical, their conversations are lent gravitas by their context. It's a kind of shorthand that works really well. Then there are these pretty out-of-the-blue moments of sublimity that can strike in such a way that beauty and thoughtfulness transcend the page and threaten to make the readers exterior life more beautiful as well. It's a good book that tries to deal with hopelessness in a manner that is warm, cozy, and not entirely depressing—even if it can't avoid it entirely.

Persephone

by Loic Locatelli-Kournwsky (translated by Edward Gauvin, lettered by Deron Bennett)

144 pages

Published by Archaia

ISBN: 1684151759 (Amazon)

Man, what a beautifully illustrated book. I'd not run into Locatelli-Kournwsky's work before, but I'm officially on notice. Persephone is a delightful reappropriation of the myth of Hades and Persephone, grounded in a world of magic and science and wars and curses. This is solid work. It doesn't even matter that my daughter would LOVE it—though maybe that speaks its own kind of praise.

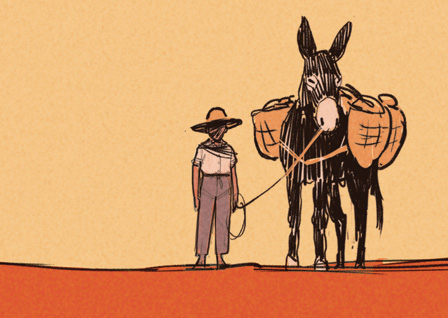

Out In The Open

by Javi Rey (adapted from Jesús Carrasco, translated by Lawrence Schimel)

168 pages

Published by SelfMadeHero

ISBN: 1910593478 (Amazon)

I haven't read the original novel this is adapted from, but if it has words, I feel like Rey has done something amazing in his adaptation, taking something with words (presumably) and rendering it instead in this spare, meditative, terror-filled space. Light on textual exposition, but heavy on atmosphere and visual narrative.

Vinland Saga

by Makoto Yukimura (translated by Stephen Paul, lettered by Scott O. Brown)

10+ vols

Published by Kodansha

ISBN: 1612624200 (Amazon)

Vinland Saga continues to interrogate Thorfinn's ideological pacifism in the middle of Viking warfare by contantly giving him near trolley problems. By using his companions as hostages, he's given choices to be passively culpable in his friends' deaths or become the beast he'd forsaken. So far he's found alternative paths, but it can't last. There are a handful of of graphic novel series that I think everyone should be keeping up with, and this is one of them.

Land Of The Lustrous

by Haruko Ichikawa (translated by Alethea Nibley and Athena Nibley, lettered by Evan Hayden)

7+ vols

Published by Kodansha

ISBN: 1632364972 (Amazon)

Land Of The Lustrous is kind of amazing in how rapidly a story about incalcitrant, functionally immortal beings evolves and changes. Some of these characters are 700 years old and harder than steel, but the youngest of their group breaks and remolds and grows and shifts in both form and personality and motivation. She doesn't just have a character arc; it's more like a character squiggle.

And the story continues to evolve dramatically. It's impossible to predict what's going to happen next. I mean, sure, one might expect a manga time skip here and there, but one that's more than 100 years and is the one time the story doesn't principally change? Didn't see that coming.

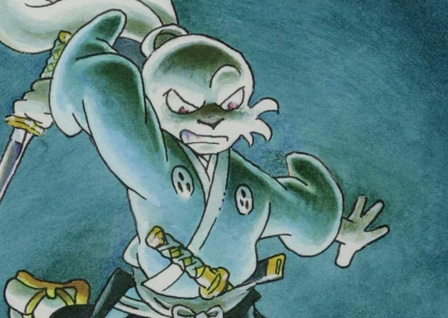

Usagi Yojimbo

by Stan Sakai

32+ vols

Published by Dark Horse

ISBN: 1506705847 (Amazon)

Usagi Yojimbo readthrough tweet thread

Usagi Yojimbo is the story of a fictional, idealized, totemic, and somewhat historical Japan. It is a story told by following (primarily) a single wandering ronin as he follows the way of the samurai, seeking enlightenment, honour, justice, and the beauty of living. Due to his wandering nature, the reader encounters a breadth of stories, regions, and cultures. These tales unfold circa 1627 and create, despite their (sometimes) almost mythical hue, a worthwhile vantage into real and historical Japan.

Sakai peppers his narrative with the fruit of a lot of research. The most popular of his stories, “Grasscutter,” begins with a lengthy-though-entertaining excursus into the mythological origins of Japan and her people. A shorter story, “Daisho,” explains the craft with which the samurai’s sword-pair is forged and the importance those two swords (called daisho) hold to their owners. Other chapters include overtly educational bits on kite-making, pottery-making, and the intrusion of the West into the Far East. And even when he isn’t completely halting his telling in order to instruct the reader, Sakai weaves a story that posits a seamless, discreet form of education—taking part in the story by simply reading it, Sakai’s audience is constantly learning more and more about a dead and foreign culture.

One of Sakai’s great talents is in his visual storytelling. His art flows naturally and his panel design is masterful. Some of the most beautiful pages are silent and filled with panels; each of these panels illustrates part of a picture-story that initially seems unrelated to the narrative intent but ends up providing context or mood for everything that is to follow. Sakai’s art has a wonderful, lyrical quality to it and it’s incredible that he’s been able to maintain his more-than-twenty-five-year schedule of producing one chapter per month. He really is one of the best creators in the medium.

32 vols is a lot to take in. If you want a nice place to start, to see if this is a book for you, I'd recommend read vol 28 up through the current volume and backtracking from there if the story suits your tastes. (It will.)

A Bride's Story

by Kaoru Mori (translated by William Flannagan, lettered by Abigail Blackman)

10+ vols

Published by Yen Press

ISBN: 0316180998 (Amazon)

A Bride's Story readthrough tweet thread

In A Bride’s Story, Mori deposits the reader leagues away from the British romance of manners she crafted in Emma, instead exploring rural and nomadic life along the Western track of the Silk Road during it's diminishment in the Great Game era. While Mori has so far largely focused her attention specifically in what is probably central Kazakhstan, near the expanding Russian border and off a bit from what used to be the Aral Sea, she's been simultaneously following a narrative track that allows her to explore increasingly Muslim lands as she follows a character's trek around the Aral and south around the Caspian on his way to Ankara in Turkey. The cultures she describe are rich in a heritage and practice that will be largely unfamiliar to the average Western reader. This is a land of yurts, shepherds, big families, khanates, delicate carvings, intricate weavings, and ornate embroideries. Much of A Bride’s Story serves as educational documentary, explaining carefully the importance of these facets of the peoples the story concerns—and it’s a mark of Mori’s talents that these lessons are never dull. The story, while pausing its plot elements for a description of tribal politics or the importance of rug-hanging, is built and embellished and given life through these brief excursions.

The most obvious of the more unique aspects of the culture Mori explores in A Bride’s Story is this people’s tradition for youthful marriages. The author explains in her endnotes to the first volume that the average marrying couple in the region would have been fifteen to sixteen years of age. For dramatic purposes here, she adds and subtracts four years from the average for her principle couple—though in a subversion of the trope, the bride is twenty and the groom only twelve. This creates numerous opportunities for thoughtful consideration of how different cultures might deal with the man/woman dynamic—as well as plenty of related awkwardness for both reader and characters alike. Amir, the bride, is often torn between mothering her young husband, Karluk, and approaching him like a young woman who is gradually falling in love. Further adding to the dynamism of the work is the fact that at twenty years old, Amir is viewed by her society as an old maid and there is no small concern that Karluk may have been slighted by being given a wife who will likely bear him few children. Amir, therefore, is eager to please her husband and new family, which gives Mori ample opportunity to display the bride’s considerable talents. Amir hunts, herds sheep, embroiders, shows a talent at horsemanship to rival any of the men in the family, and has a good decorative sense.

A Bride’s Story offers contemporary readers a delightful opportunity to exercise the skill of reading and enjoying a text without finding moral agreement with the circumstances, actions, or particulars of its protagonists. For this reason, A Bride’s Story may even be desirable to get into the hands of younger readers (despite some occasional nudity—or substantial nudity once vol 7 rolls around since much of that volume occurs in a women's bath house) if for no other purpose than to promote this critical ability at an early age. Mori makes this an elementary text for this kind of exercise. Almost no American reader will approach the text thinking it good or appropriate that a grown woman should marry a boy who is only straddling the boundary between childhood and puberty—yet that is the circumstance this culture forces on its two very winning protagonists. Further, the reversal of the autumn-spring relationship trope presents opportunities to consider the contemporary sexual politic. As well, it’s interesting to see a situation in which a clearly competent, intelligent, and mature woman willingly places herself ultimately under the authority of a child (a kind child who evidently cares deeply for his new charge, but nonetheless…).

And volume 10 not only has Karluk getting older, not only has Tileke getting to seeing a hawk, not only has a major ramp-up in the Great Game politics, but also features the return of Talas!

Abara

by Tsutomu Nihei (translated by Sheldon Drzka, lettered by Eric Erbes)

418 pages

Published by Viz

ISBN: 1974702642 (Amazon)

Abara may be the perfect introduction to the genius of Tsutomu Nihei. It's got that wild scratchy wunderkind art, but with more dialogue and exposition than Blame or Biomega. (I mean it's still belligerant chaos and odds are at the end of the day you won't actually know what happened, but you get a little more foothold here.) It's still raw Nihei before he saniztized and minimalized in Knights Of Sidonia and then further minimalized in Aposimz. (I actually love minimalized Nihei, but it's nice for a new reader to see the artist's roots.) It's also self-contained, filling only a single volume.

The Grot

by Pat Grant and Fiona McCabe

Self-published

Read here

It's been a while since Blue or Toormina Video were released and I'd been wondering what Pat Grant was up to. The Grot is it and I'm pretty impressed. It's in-progress and I don't know how long it's planned to be but everything so far is worth paying attention to.

In The Grot, the world's gone down the bowl and things like fuel seem a distant memory. Cars and ships run on pedal power and there's been huge speculator boom in the Swamp. Patches of a glowing green substance (grot) have been discovered and Everyone who wants a better life has left for the Swamp to do a bit of prospecting. It's all about as sanitary as you would expect of a place called the Swamp.

It's an ugly place full of ugly people. Grant's work takes on a distinctly misanthropic tone. This may be veneer because the story and characters are simultaneously buoyed by empathy and hope. These people are ugly and terrible and selfish BUT they are propelled by dreams and desires that we can probably all smell in our own motivations.

Delicious In Dungeon

by Ryoko Kui (translated by Taylor Engel, lettered by Abigail Blackman)

6+ vols

Published by Yen Press

ISBN: 0316471852 (Amazon)

It took me a year before I was willing to pick up Delicious In Dungeon. 1) I'm not a fan of fantasy stories (though I will occasionally really enjoy this or that entry into the genre), so I don't go looking for new fantasy books in which to invest my time. 2) While I've nothing against food book, that niche will never be a draw to me and my pedestrianly picky palette.

Still, worthwhile people wouldn't shut up about Delicious In Dungeon, so I thought I'd give it a try. Within a week, I'd tracked down and read all six available volumes.

Plainly then: this book is a pure-hearted joy. I didn't expect this much humour, really. I caught myself laughing (out loudish even) more times than I can count. Not only that, but the characters became friends in a way that I don't usually experience while reading. I actively want good things for them. I want them to be happy. I want them to find some friggen great monsters to meal. And I want them to solve the whole dilemma with Laois' sister, because man it hurts to see them like this.

The Girl From the Other Side: Siúil, A Rún

by Nagame (translated by Adrienne Beck, lettered by Lys Blakeslee)

5+ vols

Published by Seven Seas

ISBN: 1626924678 (Amazon)

Basically, there's this little girl who was left behind outside the city walls where the cursed outsiders dwell. Being touched by an outsider means that you too will be cursed and will turn black and grow horns like they do. Only this little girl lives in a small cottage with one of the outsiders who is bent on protecting her and teaching her. He looks like a monster but he worries about telling her the truth about how she was left behind by the Auntie whose return she eagerly awaits. There is the mystery and the politic, but at the end of the day, this is about a little girl in a dark world.

It bums me out that this Girl From The Other Side isn't complete, in the can, and on my shelves, because I want them all—because so far this series is straight magic. It's beautiful, spare, touching, and imaginative. It doesn't overplay its hand and it's a haunting delight. And reading the books slowly, taking time with each panel, you really get the sense of how essential the concept of proximity is to everything that happens between Sense (the guy with the skull-and-horns) and Shiva (the girl).

Happiness

by Shuzo Oshimi (translated by Kevin Gifford)

8 + vols

Published by Kodansha

ISBN: 1632363631 (Amazon)

Shuzo Oshimi, the nutball (in an awesome way) behind Flowers Of Evil, Inside Mari, and Trail Of Blood) is putting out maybe the first vampire story that's caught my interest. There's a solid mix of stuff common to the subgenre *and* stuff that is more in line with Oshimi's unique set of interests.

Beyond the many weirdnesses at play, Oshimi draws the heck out of the book. He sometimes veers into straight-up surrealism when depicting the experience of his vampiric characters—and it works colossally well.

Also: while I was initially reluctant to categorize this as much of a horror story, that ambivalence has long since passed and this has become one of the most horrifying, revolting books I have. There's some real stomach-turning business up in the midst of all the wild, pretty art that Oshimi is putting out here.

Come Again

by Nate Powell

272 pages

Published by Top Shelf

ISBN: 1603094288 (Amazon)

Nate Powell is one of my favourite creators. Especially when he's doing his own stories, he has a penchant for the magical, for the mysterious, and for the unnerving. Come Again fits right in there alongside Swallow Me Whole and Any Empire. And as usual, Powell draws the hell out of the book.

I will say that for two reasons wholly wrapped up in myself and not reflective on the q1uality of the work here, this is my least favourite of Powell's books. I still recognize it as being Very Good, but there were a couple hurdles to my reading enjoyment.

1) I hold great antimpathy toward adulterous couples and the destruction their petty selfishness instigates. On the one hand, I know several people who've cheated on their spouses and I can still be friends with the repentent among those because real people are still people and are usually worth loving. But with fictional characters, I find myself drained of all sympathy. Which makes it hard to get invested when a book's protagonist is in the midst of colossally wrecking everything and justifying the whole trainwreck in their self-serving inner monologue. It's just one of my idiosyncracies.

2) I don't actually like poetry and Come Again uses a bit of poetic form in some of its narration. My wife thinks this is a character flaw of mine. She thinks I'm broken inside. And she's probably right. Be that as it may, poetry and song lyrics are opaque to me.

So that out of the way: Come Again is really neat. Powell does interesting things with the colourspace in the usually monochrome book. And as per his interests, there is again a metanatural Thing going on in the story. Metanatural Thing? Ugh. I'm really wiped out writing this and it shows. I'd like to say I'll come back later and rewrite this so that you'll actually be inspired to pick up the book, but I probably won't because I'm too busy in real life trying to pull my life together. So, uh, buy Powell's books. Hell, buy all his books.

To Your Eternity

by Yoshitoki Oima

7+ vols

Published by Kodansha

ISBN: 1632365715 (Amazon)

To Your Eternity readthrough tweet thread

I wouldn't doubt if Oima came up with the idea of To Your Eternity to answer a bet with an editor speculating just how many times she could devastate readers. The very nature of To Your Eternity (the story of an immortal who survives generations and generations) means that any character beyond the protagonist that you get attached to is going to die. 100%. It's a sure thing. If that bums you out too much, don't read stories about immortals. 2018 saw both my favourite and least favourite arcs in this story. Basically I'm totally onboard except for I didn't care for the first half of the Prince Tasty Peach arc (though it gets *much* better in the backend).

Spirit Circle

by Satoshi Mizukami (translated by Jocelyne Allen , lettered by Lys Blakeslee and Rachel J. Pierce)

6 vols

Published by Seven Seas

ISBN: 1626926018 (Amazon)

With Spirit Circle, Lucifer And The Biscuit Hammer, and the recent anime Planet With, Mizukami proves himself reliably imaginative creator. Spirit Circle, despite being conceptually fascinating, may actually be the most mundane of his stories I've so far encountered. Two kids and their friends are somehow tied across lifetimes and continually reincarnate in intimate proximity to each other. The story begins as the new girl at the school proclaims that she is going to kill the protagonist. Because he is baffled, she provides him the means to investigate his past lives to discover why he must be murdered. The whole thing is a lot of fun and gets conceptually pretty wild by the end.

Wild's End

by Dan Abnett and INJ Culbard

3 vols

Published by Boom

ISBN: 1608867358 (Amazon)

I'm not super into books about zoomorphs (my longstanding love for Usagi Yojimbo is a notable break from my genreal rule), and I've read enough revamps of War Of The Worlds to last me a lifetime (one even written by Culbard's own occasional creative partner, Edginton). I would have left Wild's End unread (despite praise from elsewhere) had it not been for Culbard's involvement. (I've been a fan of his illustrative storytelling since reading his and Edginton's adaptations of Sherlock Holmes nearly a decade ago.) And happily, Abnett and Culbard pull something magical out of their hat. This is perhaps the first time that I've been excited by an alien invasion story since I read the original War Of The Worlds in fourth grade. Their cast of characters is luminous (sometimes literally) and it's their stories that give life and meaning to the soulless invasion of these foreign beings.

Also, and this is something remarkable. I pretty much never read the prose extras that some authors will include in the back-matter of their comics. I think I read a paragraph and a half of Alan Moore's backmatter for one of the League Of Extraordinary Gentlemen issues. That kind of stuff really knocks the wind out of my comics-reading sails. I'm here for the concatenation of word and picture. It's in that chemistry that I find my joy. And I don't know what prompted me to give it a shot, but I devour the back matter in each chapter of Wild's End. They are superbly accomplished and they add so very much to the experience of the story and these characters that the book would feel hollow without them.

Brazen: Rebel Ladies Who Rocked the World

by Pénélope Bagieu

304 pages

Published by First Second

ISBN: 1626728690 (Amazon)

Despite a title and cover that promise a damn-the-man (and men) rallying cry against the hegemony, Brazen offers something completely different: a celebration of the astonishing breadth of ingenuity and interest within the scope of the human endeavor. I asked my wife to summarize the book and she described it as Interesting Women Doing Interesting Things.

So marketing decisions aside, what does Brazen have to offer? To start, Brazen holds a great set of biographical sketches. Thirty women from the past and present, each with their own personalities, goals, values, and trajectories. One is a cartoonist, one a vulcanologist, one a libertine, one a rapper, one an astronaut, one a dioramist, and one the face of a revolution against a dictator. Et cetera. One of the strengths of the book is how varied all these stories are. You have a Chinese empress on one hand and then pages later a woman trying to save a lighthouse through terraced planting. The whiplash is refreshing. And sure, along the way a couple of these women could actually be considered rocking the world, and some are rebellious. Most though are just doing their thing and their thing just happens to be pretty interesting.

Bagieu's art is fun and lively as readers of her other works will find. Unfortunately, the US release shrinks the work down by nearly 25% to make a more compact, shelf-friendly edition—which loses the reader the sense of her linework. Still Bagieu's sense of character shines through and one of the treats is seeing Bagieu age each figure through life over the course of 4 to 6 pages (the usual amount she dedicates to each woman featured).

I don't have any particular affection for biography, but I found the collection alluring and enjoyable for its brisk treatment of its subjects, which even prompted me to look up more to their stories online in a handful of cases. I was familiar with the stories of about half the women featured, so it was delightful to discover the rest.

There was another book similarly framed this year, Femme Magnifique, and looking through it serves to magnify why Bagieu's version is so strong. Femme Magnifique treats way more women and their stories than Bagieu is able to get to but whereas Brazen is a cohesive book with a singular vision and mode, Femme Magnifique is a chaos of art styles, writing styles, methods of telling. It's a constant experience of whiplash and even the better stories included get lost—the price of anthology, really. With Bagieu, we always know where we are and what we're going to see.

Princess Jellyfish

by Akiko Higashimura

9 vols

Published by Kodansha

ISBN: 1632362287 (Amazon)

Oh man Princess Jellyfish was a lot of fun. Higashimura takes a cast of characters I don't really like and lets them (most of them at any rate) charm me into enjoying their antics. Both my wife and I audibly laughed or chuckled our way through the series. And while at nine vols it feels a bit padded out (five probably would have been better), we both pretty thoroughly enjoyed our time in her world.

Wotakoi: Love Is Hard For Otaku

by Fujita

3+ vols

Published by Kodansha

ISBN: 1632367041 (Amazon)

Wotakoi is some good enjoyable romance comics where, while the cast aren't exactly proceeding through their love lives in "normal" fashion, they are certainly less hidebound to many of the tropes we're familiar with through what manga that has crossed the Pacific. The lead couple (childhood friends, actually) start dating in the first chapter. Really, the only thing that gets in their way is the thing that draws them together: their individual geekdoms. It's a cute book and if you've watched the anime on Amazon, you can start getting new story starting with vol 3 (though vols 1 and 2 have their charms over the anime as well).

Erased

by Kei Sanbe

4 vols

Published by Yen Press

ISBN: 031655331X (Amazon)

After the big surprise at the end of vol 3, I was thirsty to find out what would happen in this time traveling murder mystery. Sanbe largely delivered, I think, and he made a nice 4-vol thriller filled with this really touching relationship in the middle.

Again!!

by Mitsurou Kubo (translated by Rose Padgett, lettered by EK Weaver)

7+ vols

Published by Kodansha

ISBN: 1632366452 (Amazon)

Synopsis: It's high school graduation and bleached long-haired loner Imamura is friendless and scary. Through an accidental fall on an apparently magic staircase, he and popular girl Fujieda get sucked back into their 10th grade selves. Fujieda finds her knowledge of the future is screwing up everything for her but Imamura joins the school's ouendan cheer squad (ouendan is a loud chant-based kind of traditional Japanese cheerleading). And things, of course, develop from there.

If you're looking for something in the vein of A Distant Neighbourhood but not done by one of the great masters of comics and more silly and fun, Again!! might strike the right note for you. There's a lot of heavy stuff going on in the world and you're allowed to get comfy with some lighthearted stuff every now and then.

Also, vol 4 takes what could have been a simple go-back-in-time-and-relive-my-past-but-better conceit and complicates it pretty marvelously.

The Prince And The Dressmaker

by Jen Wang

288 pages

Published by First Second

ISBN: 162672363X (Amazon)

Jen Wang's art is always lovely, cartoony but confident. And the story here is just some comfy fun. It's not going to make or shatter worlds, but it will make you enjoy the hour you spend in its pages.

Destroyer

by Victor Lavalle and Dietrich Smith (coloured by Joana Lafuente, lettered by Jim Campbell)

160 pages

Published by Boom

ISBN: 1684150558 (Amazon)

While there are some issues with the art (eg Frankenstein's monster's size shifts pretty dramatically from scene to scene), the story is engaging and pairs well with Upgrade Soul, exploring transhumanism, monsters, and the black experience in America.

Mort Cinder

by Hector German Oesterheld and Alberto Breccia

224 pages

Published by Fantagraphics

ISBN: 1683960793 (Amazon)

What amounts to a kind of Twilight Zone-y mystery/horror serial is elevated by some truly luscious art. Probably the best wat to read this would be to read a strip a day with your morning coffee-and-toast or whatever it is you millennials are eating in the morning since you killed breakfast cereal. Same is probably true for Osterheld's other serial, the outsanding El Eternauta.

Spill Zone

by Scott Westerfeld and Alex Puvilland (coloured by Hilary Sycamore)

2 vols

Published by First Second

ISBN: 159643936X (Amazon)

If you want a little bit of breezy sci-fi horror in your life, then be sure to check out Spill Zone. Not only is it a lot of fun, but you'll be able to see firsthand Hilary Sycamore's amazing work as a colourist.

Infidel

by Pornsak Pichetshote and Aaron Campbell (coloured by José Villarrubia, lettered by Jeff Powell)

168 pages

Published by Image

ISBN: 1534308369 (Amazon)

And if you want a little bit of breezy horror horror in your life, then be sure to check out the murderous ghosts in Infidel.

LAAB

by Ron Wimberly

44 pages

Available in digital here

For those interested in the cultural discussion in comics, I highly recommend checking out Ron Wimberly's broadsheet newsprint magazine, LAAB. (Currently available in digital form.) LAAB is a mix of comics and prose journalism that dissects black representation in sci-fi, comics, and culture. It would have been higher on my list had it included more comics.

There's a lot of great stuff in there and I found the article How I Learned To Stop Worrying And Love The Cape particularly fascinating as it posits that the Marvel/DC superhero mode is natively opposed to the black experience and black interests—largely since superheroes are devoted to propping up/securing the white capitalist hegemony against the ideological supervillains who aim for a new structure.

Glorious Summers

by Zidrou and Jordi Lafebre

5 vols

Published by Europe Comics

Kindle edition: (Amazon)

Lafebre's illustrations are just really top notch. I've only been able to get partway through the series (as currently it's only available in English digitally, and reading comics digitally is The Worst), but hopefully with the release of the fifth volume, maybe there will be interest enough for a print collection. I would be very much there for that.

Girl Town

by Carolyn Nowak

160 pages

Published by Top Shelf

ISBN: 1603094385 (Amazon)

As with most anthologies, Girl Town's story quality is variable. There is one Good story and one Great story—great enough that I would have included Dana's Electric Tongue even if it had been the only story in the collection. I think the ideal version of Girl Town would have been just a collection of Diana's Electric tongue and Radishes. The other stories rate from fine to mediocre, and (save to illustrate Nowak's versatility) their inclusion diminishes the book a touch.

Made In Abyss

by Akihito Tsukushi (translated by Beni Axia Conrad, adapted by Jake Jung, and lettered by James Gaubatz)

6+ vols

Published by Seven Seas

ISBN: 1626927731 (Amazon)

Vol 4 is the first volume of Made In Abyss to include story not covered in the anime. And man, as dark as things got in the anime, things just get more and more bleak for our child adventurers. The white whistles, as we've gathered, are truly monsters.

And allow me to wring my hands a bit but I don't really know what to do with the nudity in Made In Abyss. Like, the in-story stuff feels okay, probably. It fits in its place and forwards the themes of humanity vs artifice. But tween nudity on the contextless endpapers? Dodgy.

Check Please

by Ngozi Ukazu

1+ vols

Published by First Second

ISBN: 1250177952 (Amazon)

Check Please will probably get most of its attention for being a cute romance, but honestly, this could just be about pie-making Bitty and his hockey pals playing hockey and doing college stuff and I would still be on board. I will say that picking it up and looking at the art, I assumed it was in the ballpark of Smile or Drama and almost tossed it on my daughter's read-pile. Guys, it's more mature than a 9yo would get, so don't get it for your kids unless your kids are fine with grown-up language and grown-up topics.

Welcome To The Ballroom

by Tomo Takeuchi

10+ vols

Published by Kodansha

ISBN: 1632363763 (Amazon)

This is a sports story and one of those sports stories about the prodigy player who got a late start on the sport and is going to quickly make up for lost time because he’s that good. It’s a common enough formula, but Welcome To The Ballroom performs its steps very well. It’s graceful on the fundamentals while throwing in some delicious variations for a pizazz that serves to elevate the rest of the story. In the five vols I’ve read so far (I’m enamoured enough that I plan to continue with the series as new vols are released), fifteen-year-old Fujita moves from entirely inexperienced amateur to gifted would-be competitor. He begins the series aimless and struggling to find an interest as he is being pushed to choose a high school to attend. Accidentally, he finds himself in a dance studio with members devoted to competitive ballroom dance. While initially embarrassed and hoping nobody discovers him there (male dancers have about as great a reputation amongst other teens in Japan as they do here), Fujita sees a video of what competitive ballroom dance is actually like and in set alight. He has a direction now and will rocket toward it through the rest of the story, meeting obstacles and overcoming them or using his defeats by them to improve himself. (See? That sports story formula. AKA life story formula.)

If you’ve read sports manga before, you’re probably familiar with the story beats, but where Welcome To The Ballroom shines is in its visual depictions of athleticism. In Polina, Bastien Vivès ably depicted his ballet dancers in spare, minimalist gestures, giving the dance a quiet fluidity emphasizing the grace and beauty of the form. Welcome To The Ballroom doesn’t remotely attempt this. Takeuchi’s dancers are vibrant, bursting with frenetic energy. They are electric and exciting and Takeuchi draws flourishes to highlight some of the emotional energy exploding beneath the skin. Fire will crackle off the clasped hands of a couple as they waltz. A character will be engulfed in flame to express his rage or passion. The skin of another will bristle and steam as their waning strength rejuvenates to pull out one last showstopper. And the sweat.

Takeuchi does one thing I’ve never seen in a comic about active characters before. They are drenched in sweat. Rivers of it pour from their hairline down their faces as they exert themselves. It’s an incredibly small detail but it goes so very far in selling the world of these competitions. The beautiful, gorgeous women in this book do not glisten. They sweat. Buckets. It’s perfect and real.

So far at least, Welcome To The Ballroom doesn’t escape its tropes or formulae, but it’s not trying to. Instead, the book is playing entirely within the established realm and doing so with verve. It’s nailing all the steps and avoiding many of the pitfalls. It’s sweeping across the floor getting it done and showing how to do it. Welcome To the Ballroom doesn’t have the emotional range or sweep of Cross Game but does make its sport thrilling even for those, like me, who don’t have much actual interest in the activity depicted.

I'm still enjoying Welcome To The Ballroom, but I am going to be soooo happy when Tatara and Chinatsu finally stop fighting and just start dancing. It feels like this has been going on forever.

Waking Life

by Ben Humeniuk

2+ vols

Published by Comicker

ISBN: 0997487321 (Amazon)

There's something about revisitations to Little Nemo that always threaten to keep me at arms length. It's not that I don't feel like anyone can do anything interesting with the subject (stuff like Ron Wimberly's and Farel Dalrymple's work in the homage book, Little Nemo: Dream Another Dream show it's possible). But I'm always a little skeptical that they can pull it off. After all, Nemo is a character deeply embedded in the zeitgeist of 1906 America and all the good and terrible things that come with that. I haven't picked up Eric Shanower's recent Nemo book for this reason. Mostly, I just don't want to encounter a Nemo that fails its source.

When I realized (in its opening pages) that Humeniuk's Waking Life is a sequel to Little Nemo, I was reluctant to go further. Waking Life's art does nothing to evoke the beauty of Winsor McCay's original work - though to be fair, I can't think of more than a handful of artists who could be up to the task. But! I had the work in hand so, really, why not give it a fair shake.

Waking Life neatly avoids the concerns I have with 21st century revisitations to Little Nemo by setting it in the 21st century, long after Nemo stopped visiting Slumberland, stopped being a child, and likely stopped being a living person at all. It opens with Morpheus' daughter in the common set-up, needing a playmate. This time, however, the Princess switches things up. Instead of Morpheus always choosing her playmate, she's going to do it herself.

So she chooses Robbie and the two have hundreds of wonderful adventures - until Robbie hits the teenage years and wearies even if only in his dreams of their childish adventures. He's got more important stuff to wrestle with: the social hierarchy of high school, a single mom who leaves him a latch-key teen as she works long American hours at her law firm, and the dream of being an artist that nobody cares about so long as it doesn't get in the way of his studies.

The princess, not willing to lose another playmate the way she's lost all her previous ones, takes matters to her own counsel and figures, Hey, if the waking humans can get to Slumberland, why can't the dream beings get to the Waking World? And boom, there she is and Robbie's life suddenly becomes more exciting and more difficult - but hopefully more fun and rewarding at the same time. We'll see how it plays out.

The Battle of Churubusco: American Rebels in the Mexican-American War

by Andrea Ferraris

200 pages

Published by Fantagraphics

ISBN: 1683960572 (Amazon)

Late in the Mexican-American War, the Mexican Army (including St. Patrick's Battalion) lost a battle at Churubasco, 5 miles from Mexico City. Saint Patrick's Battalion was composed of deserters from the US Army sympathetic to the Mexican plight, most likely because of a) shared Roman Catholic heritage, and b) the fact that their Irish, Italian, etc immigrant status left them abused by the common American soldier.

This graphic novel opens moments after the Patricios' defeat and we witness the cacophany of war's aftermath and the branding and execution of the surviving deserters. Then it slips a week or so back before the battle and on up to moments before. We never see the details of the battle unfold, but don't really need to.

Ferraris' Battle Of Churubusco flows quickly. It feels less like a novel and more like a short story, focused not on the details of character or strategy, but instead in place to evoke a sense of raucous terror. It wouldn't be unfair to say that Ferraris positions the US forces as the antagonist though he does both create a largely sympathetic figure in the US captain who tracks down the Mexican stronghold and orders the attack as well as show Mexican forces relying on subterfuge to recruit peasants to their cause. It's a dark book and a brisk book and appears drawn entirely in dark pencils.

Zenobia

by Morten Durr and Lars Horneman

60 pages

Published by Triangle Square

ISBN: 1609808738 (Amazon)

Zenobia was one of several books about the refugee experience to come out in 2018 and is probably the one I like best, if only because it doesn't take the easy way out like Illegal does. The book's title refers both to 1) the name of the queen of the Palmyrene Empire, an inspiration to Amina, the book's young protagonist, and 2) and a cargo ferry that sank near Larnaca in 1980. Both play an important thematic role in describing Amina's journey. The book begins with Amina's refugee boat capsizing in a storm off the coast of Cyprus and much of the story is told via flashbacks. It's a somber tale who's thread we've seen before, but it's well done here and the use of the Palmyrene queen helps the story hit home a little better.

March Of The Crabs

by Arthur De Pins (translated by Edward Gauvin, lettered by Deron Bennett)

3 vols

Published by Archaia

ISBN: 1608866890 (Amazon)

March Of The Crabs concerns a particular species of crab (that I'm not sure actually exists) that is small, has no predators, and cannot turn. These little guys can only move side to side with no deviation. So, for the duration of their lives, the walk back and forth along the single vector into which they were born (barring external acting forces, like a wave or something). A crab who finds herself fancying a crab she walks parallel to will never have the opportunity to touch that crab.

Sad life.

Having no predators and being outside the food chain, these crabs have never had the need to evolve. But now, this one crab has an idea, one that will begin a change across the race. He hops on the back of a crab going perpendicular to his own path and through teamwork, they can travel anywhere along that x and y coordinate grid. And there are more surprises in store for the species—and all the political turmoil that naturally goes along with that kind of thing.

The Bridge: How the Roeblings Connected Brooklyn to New York

by Peter J. Tomasi and Sara DuVall

208 pages

Published by Harry N. Abrams

ISBN: 1419728520 (Amazon)

The Brooklyn Bridge remains one of the lasting testaments to the ingenuity of the industrial age, an engineering work that spanned a gulf 50% longer than any bridge in its time. And the fact of its creation, evidenced by the 2.5 million vehicles that travel it daily, is only part of its wonder. Perhaps more fascinating than the bridge itself is the story of its formation.

Tomasi, a self-confessed superfan of bridges, details the lives of John and Washington Roebling and Washington's wife Emily, who directed the work for nearly 80% of the bridge's construction after Washington was injured by the tremendous pressures in one of the bridge's two enourmous caissons. Tomasi's book gives me the same kind of vibe as Larsen's Devil In The White City, where an ostensibly dull story (in one case the building of a bridge, in the other the building of an exhibition grounds) turns out to be deeply fascinating and even, perhaps, thrilling. After I finished reading, I immediately went online and looked up more information on all three Roeblings.

Where Tomasi's foray into the history of the Winchester Mystery House used the astonishing illustration talent of Ian Bertram to create a spacey, curdling atmosphere of hallucinatory terror, here the art is subdued and plain. It gets the job done but doesn't inspire Oohs and Ahhs. I suspect that some of that may be design as a) the telling here is more reverentially documentary, and b) this reads as though it's meant to appeal more widely across the age demographics—The Bridge wouldn't be out of place shelved in a sixth grade classroom. And while her work here doesn't hold the wild flash and pop of something like Bertram on House Of Penance, there are many things to appreciate, not the least of which is how she ages characters from year to year—important in a book that spans roughly 25 years.

The Unwanted: Stories of the Syrian Refugees

by Don Brown

112 pages

Published by HMH

ISBN: 1328810151 (Amazon)

While Zenobia was a particularly artful brush at a particular kind of refugee story, The Unwanted is what I would recommend to classrooms. Don Brown tells story after story, sometimes several in a page, of many of the individuals who fled the turmoil and horror of Syria these last years. It's a heartbreaking read but necessary, especially when one considers who reluctant nations are to absorb these men, women, and children who give up everything in hopes of being able to live, to survive, and maybe one day to flourish. This is one of those books designed to build empathy in readers. And while I wish the publisher would have hired a letterer, the book is still desparately worthy of your time and attention.

Want to support me?

There are basically a couple ways to support me, if that's something that sounds fun or valuable to you.

1) Through Patreon.

2) Through buying my stuff. I've got an etsy shop to sell comics, books, and prints.

Other Cool Stuff

1) I taught an afterschool class this year on How To Make Comics, geared at 2nd through 6th graders. Two particular kids knocked it out of the park and I discuss their comics in tweet threads here:

For my own work, while I'm working as time allows on a full length graphic novel series, I did complete a neat little 31-page micro-graphic novel called Ghost Towns. You can read it here for free:

Notable Exclusions

There are a lot of books that didn't make it on the list that I'll get questions about or otherwise feel I should mention.

Books That Almost Made It

This is all stuff that was ranked on some incarnation of the list, but was eventually pushed off in favour of other works. Honestly though, probably any of these could be exchanged with any of the last ten books on the list. They're all good and it was painful to cut them.

- Warm Blood - Josh Tierney and his obscenely long list of illustrators is putting out a pretty rad story.

- Horimiya - This is still enjoyable, but nowhere near the revelation it was a couple years back.

- My Boyfriend Is A Bear - Fun book about a woman dating a bear who's kind of like a real bear but also kind of like an person.

- Blackbird Days - A nice anthology from Fior with some fine-I-guess stories and a couple really solid ones.

- Wires And Nerve - The finale to the two-part sequel to Meyer's Lunar Chronicles series. It was fun.

- Stray Bullets - Stray Bullets is amazing, but Sunshine And Roses focuses on Beth, who is not my favourite protagonist. I really just want more Virginia.

- Dam Keeper - Neat series. Looking forward to seeing where it'll go.

- Nameless City - This was a good adventure story from Faith Erin Hicks. I still prefer Friends With Boys, but this is solid work. And my daughter enjoyed it!

- Deadly Class - The writing in this is a bit overdone, but the art's great and the story sometimes fires on all cylinders.

- Interviews With Monster Girls - Kind of a stupid idea but I really do like these guys trying to figure out how demi-humans work.

- Woman World - Basically a series of humour strips. Not as good as Far Side, but better than Nancy? I was usually fairly amused.

Navel Gazing

Coming up with a ranked list of things for a personal site or post on Facebook is entirely different in nature from ordering things for a Serious Critical Outlet (which I vaguely pretend to be). I can't just post What I Liked because 1) I have a site mission to consider and 2) for the list to be recognized as worthwhile to most readers, it has to contain enough of those things that other people would list to seem legit.

And while I never cheer on popular books that I hate just for the concept of earning legitimacy, there's always a bit of artificial list reorganization that is maybe even subconsciously designed to appeal to a readership. And maybe I'll even bump up a smallpress indie book that you can't even buy because Man that makes it feel like I'm serious about comics and you should trust me. (By the way, I *am* serious about comics and you definitely *should* trust me.) But maybe I won't do that. Most of these motivations are present but subconscious.

Does the fact that I'm on friendly terms with some creators give those books a bump? I don't see how it couldn't, even if I'm not conscious of it happening. When you read a good book by a stranger, you think, "Hey that was good!" When you read a good book by a friend, your naturally warm feeling for that other person blends with your experience of the book (because nothing social occurs in a vaccum) and now you think, "Man, that was a good book! I loved it!" And of course friendship also tends to soften criticism as well. Because we're not robots, you and I.

Also, I have to balance in some sort of subjective rubric for valuating a) What I liked with b) What is valuable and c) What is high in craft-quality. Every year, I find creating the list more daunting and more frustrating. Especially since not only is #26 not substantially "better" than #27 but also #26 is likely not substantially better than #45. I mean, it's a good problem to have. Lots of good books to read. And more every year. Essentially, we will never run out of good comics to read. It's like a golden age or something.

Good Ok Bad features reviews of comics, graphic novels, manga, et cetera using a rare and auspicious three-star rating system. Point systems are notoriously fiddly, so here it's been pared down to three simple possibilities:

3 Stars = Good

2 Stars = Ok

1 Star = Bad

I am Seth T. Hahne and these are my reviews.

Browse Reviews By

Other Features

- Best Books of the Year:

- Top 50 of 2024

- Top 50 of 2023

- Top 100 of 2020-22

- Top 75 of 2019

- Top 50 of 2018

- Top 75 of 2017

- Top 75 of 2016

- Top 75 of 2015

- Top 75 of 2014

- Top 35 of 2013

- Top 25 of 2012

- Top 10 of 2011

- Popular Sections:

- All-Time Top 500

- All the Boardgames I've Played

- All the Anime Series I've Seen

- All the Animated Films I've Seen

- Top 75 by Female Creators

- Kids Recommendations

- What I Read: A Reading Log

- Other Features:

- Bookclub Study Guides