Ranking things is an inherently stupid idea. I mean, if you're going to take it very seriously, it is. By this point we're all aware that these things are subjective and susceptible to biases, personal histories, tastes, and a slight flux in the barometer. There's little objective in art appreciation. In the micro, at least. In the macro, we can with some confidence say things like Jack Kirby was a better artist than Stan Lee or Moby Dick is a better novel than Twilight. But ranking? That's on the micro and when you're ranking The Best of a category that boasts ten thousand options, you're kind of just making it up.

Or to put it more positively, you're making educated guesses. Maybe highly educated guesses, but guesses all the same.

So, some ground rules about this list.

- These are all good books. Some are even great books. But for the most part, there's not going to be much quality difference between books that are 75 places apart. So Book 50 might only be a smidgeon better than Book 125.

- I'm ranking on an amorphous mix of quality in story, quality in writing, quality in art, ideological value, how much I actually like the book, and then some ephemerals like Does this book propel the form in any meaningful way?

- While I have read a lot of graphic novels (I read 400+ volumes per year), I haven't even read all of the canon choices (note: there is no canon, not really). So if you read this list and are pissed off that there's no One! Hundred! Demons! or no Berserk or no Tom King Batman—just know that this is because I haven't read those books.

- I will have forgotten books. Until two days ago, I had forgotten Twin Spica (a personal favourite). There's probably plenty of books I would add but I've just plain forgotten.

- In a week, I'll already regret some of my ordering here. I could edit this list over and over again for years and still not get at something I find completely satisfactory. But I felt it was better to get these recs out there so people could start finding their next favourite comic.

- At the end of the day this is a very personal list and reflects my tastes, knowledge, interests, and experience. Your list, obviously, would look very different. I also highly recommend you put together a ranked list of your top 500 comics. It's fun and exhausting.

Probably the best way for you to approach this list is not as a justification for your own tastes, but instead as a way discover new books that may be just your bag. That's really my intention here, to sing the news of a bunch of great comics for you to check out maybe if they sound like they might be your bag.

And with that, here's the list. I've broken it into 5 pages: 1-100, 101-200, 201-300, 301-500 (for the last 200, I'm merely providing the titles, authors, etc and no or little commentary), and a final page of end notes and explanations to wrap it up [which isn't actually there yet because I still have to put that information together]. By the way, to ground this list in time, it was published on 19 November 2018. (This is so when you run across this list in 2025 and wonder why it doesn't include the best book of 2019, now you know it's because I've been lazy and haven't updated the list.) So then:

1–1011–2021–3031–4041–50

51–6061–7071–8081–9091–100

101-200201-300301-500Afterword

My Best 500 Comics Of All Time*

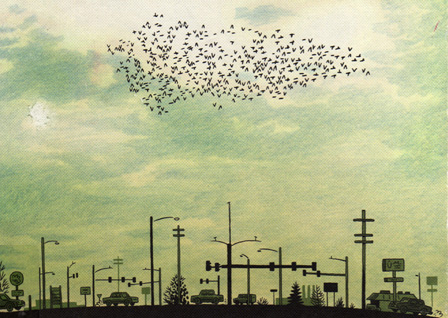

Duncan The Wonder Dog

by Adam Hines

400 pages

Published by AdHouse

ISBN: 0977030490 (Amazon)

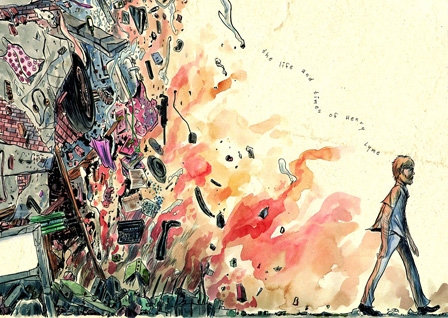

Duncan The Wonder Dog is available in print (it's a huge book) and, kind of amazingly, Hines also makes it available for free—amazing because this is my pick for best graphic novel of all time. It's not for everyone, certainly. But it's rich, thick, heartfelt and demands contemplation.

The world presented in Duncan is one that mirrors ours almost exactly—save for the fact that animals can express themselves in the language of humans. This doesn’t change much about the world order. Cattle and pigs are still herded into pens and raised for the slaughter. Dogs and cats still live as pets. And foxes still prey on rabbits. The difference is that now the cows spread rumours about why none of them ever return after leaving for the slaughterhouse while the humans who are slaughtering them lie to them, explaining that the very idea of such murder houses is just silly. Animals (with a few humans) have formed activist groups, some of which have become full-blown terrorist cells. ORAPOST is one such group and it is helmed (for the moment at least) by a golden macaque named Pompeii whose attitude and methodology are as explosive as her name. It’s a world with frayed edges, coming undone even as it seeks to forge itself into something worthwhile.

Duncan's structure is a slow-burn. At first it’s not even clear that in this world animals can talk. And not just talk in that Watership Down sort of way, where animals have voices and can communicate amongst themselves but never to man. In Duncan the animals speak as plainly as you or I do. If you ask a whining dog what’s the matter, she can simply tell you. Once it becomes clear that this is the kind of world that Hines is populating with his characters, a reader still has a hundred or so pages before the books’ protagonists are firmly establish and a plot finally rears its head.

Hines crafts an expansive story with immense value against a tremendous ethical background on broad canvas. This is the story not of the human race but of creaturely existence. And co-existence. And through Hines’ masterful technique Duncan—for all its fantastic setting—essays a profoundly moving, astonishing set of stories, each contributing to the question of co-existence in fresh, exciting ways.

Cross Game

by Mitsuru Adachi (translated by Ralph Yamada and Lillian Olsen, lettered by Jim Keefe and Mark McMurray)

8 vols

Published by Viz

ISBN: 1421537583 (Amazon)

This is the graphic novel I've read more times than any other. It could rightly be called my all-time favourite. (Even if I think that Duncan The Wonder Dog is ultimately the "better" book.) It is so enjoyable that I read all eight volumes every other year at least. Sometimes more often.

Cross Game is, overtly, about baseball. I don't care about baseball. I don't even really like it. I hate spectating sports. And yet, I devour Cross Game because though it is intimately devoted to the majesty of the game (Adachi has done more than five series devoted to baseball). I devour it because it is about so much more than baseball and that "much more" subsumes the baseball part so entirely that I begin to love the baseball part.

When it comes down to a book that I can just settle into after a stressful week or when I'm down or when it's cold out or when there's just been too much rain or when I remember how much love there is in the world, it doesn't come better than Cross Game. Whenever I loan out a copy, I'll flip through the book (as I tend to do whenever I loan out any book) and I'll experience a time skip in which I've accidentally read thirty or forty pages. Sometimes more.

These books are completely, entirely enjoyable. Adachi has had decades to perfect his storytelling craft and this is him playing at the top of his game. Cross Game is fun. Cross Original Aviator Game is funny. Cross Game is sad, is thrilling, is touching, is smart, and is well told. Cross Game is about love and family and friends and loyalty to each—and is the most compulsively readable comic I own. I love it and it always helps me feel like I'm tapping into this thing that is intensely human. It reminds me what it is to love in all of the senses of the word.

Nausicaä Of The Valley Of Wind

by Hayao Miyazaki (translated by David Lewis and Toren Smith, lettered by Walden Wong)

2 vol omnibus

Published by Viz

ISBN: 1421550644 (Amazon)

This could comfortably sit in probably any critic's Top 10 Comics Of All Time list. Maybe even comfortably in any critic's Top 3?

The story of Nausicaâ is robust. It travels a lot of territory and the narrative terrain shifts constantly. The story at page 100 is different from the story at page 200 is different from the story at page 300. Et cetera. Miyazaki keeps the reader off-balance, constantly renegotiating what his story is actually about. In the hands of a lesser author, Nausicaâ would seem a confused jumble of ideas, an evolving puzzle its own author could not solve. Fortunately, and I think most of the world probably knows this by now, Miyazaki is among the best storytellers of our age. It shows in Nausicaâ. The sureness of his authorial footing in this book is never at doubt. From beginning to end, we are on his ground and it’s a good place to be.

Nausicaâ tells the story of the post-cataclysmic Earth, a millennium after its destruction by the hands of a weaponized robotic army (presumably created by mankind herself). Humanity has barely survived the nuclear fires that tore civilization apart. The earth itself, polluted beyond its ability to heal in a normal manner, has given birth to a terrible new forest. Called the Sea of Corruption, this roiling swath of strange new flora means death to those that it engulfs, for its air is unbreathable. As land becomes more and more scarce due to this growing threat, wars break out and the future of humanity is threatened all the more. In the midst of this, Nausicaâ, a princess of a small outlying tribe, seeks to unravel the mysteries of the Sea of Corruption while negotiating a dangerous path between two warring nations. The princess herself is a mystery to all those she encounters, part chaos, part mercy, and always navigating her own path.

For those familiar with Miyazaki’s films, the art will seem a familiar prototype, an early version of what would become the Ghibli house style for the next thirty years. In tone, Nausicaâ probably closest resembles the sometimes violent action and environmentalism of Princess Mononoke (though those that weary of that message shouldn’t be overly put off by its expression here). The story is long and many panels are more text than imagery as Miyazaki attempts to sensibly exposit his narrative. The tale requires patience and perseverance, but it rewards its pursuers. There are a number of great adventures told through the comics medium, but Nausicaâ is so far—and pretty easily—among the best of show.

This was made into an animated film that is sad and tawdry by comparison. The film was made when the story was 1/4 complete. It sits as a good mid-'80s proof of concept, but it's got nothing on the comic.

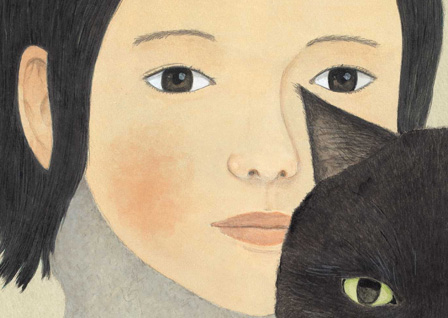

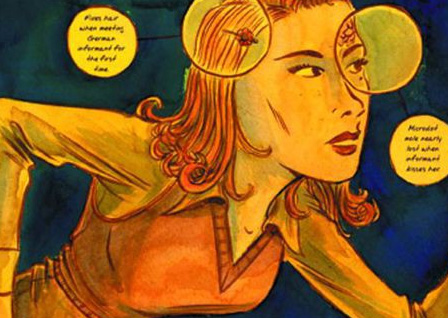

The Nao Of Brown

by Glyn Dillon

208 pages

Published by Self Made Hero

ISBN: 1906838429 (Amazon)

The Nao of Brown is a wonderful collection of visual and literary themes, marked by a compassionate visual sense and a deeply dialogical atmosphere. It’s one of those books in which word and image conspire together in a harmony unusual for comics.

Dillon is not only an impressive illustrator and designer. His art always on every page aids his story, lending voice and colour to his characters’ dialogue—and to Nao’s narration. In a work in which the majority is filled with mundane conversation, Dillon invests his characters with expression, carriage, and posture such that their story would be incomplete if only left with their words. These are real people and they are rendered realistically save for the fact that Dillon captures them in the best possible moment—all in order of course that the reality their story should be validated by their presence.

The art is gorgeous, pencil and watercolour (though these days it can be hard to tell just how much is post-processed in Photoshop—as if it mattered in the end). Dillon couches his work in a rich tapestry of visual metaphor. Rich enough at least that there’s plenty of fodder for those willing to put the work in to interpret him. Visual motifs abound. From the recurring use of the circle to foreign and foreign-esque cartoon characters, everything evokes. The pages bleed with purpose. Even Dillon’s use of colour seems to bear on his meaning. Nao wears red. All the time. Every time. Until the times she doesn’t. The Nao of Brown is such a delight to the eyes that I find myself wishing every book looked like this—despite loving much the more simple work of Chris Ware and Jason. Dillon’s art breathes, it has life. And life is exactly what his story demands.

Hellboy

by Mike Mignola (with Duncan Fegrado, coloured by Dave Stewart, lettered by Clem Robins)

14 vols

Published by Dark Horse

ISBN: 1593079109 (Amazon)

Hellboy ended in 2016. And apart from some rare bumps in the road (always due to Mignola's collaboration with another artist or writer), the series has essentially just been the best comics. The series started off in a rough place, with bold beautiful art from Mignola, but also with janky, overheated, silly writing by John Byrne. By the time of the second Hellboy story ("The Wolves Of St August"), Mignola took over the writing and the book became the most amazing thing. And then it got better. And better.

And then, six years ago, Hellboy died. And went to hell. The final two volumes are just him wandering the non-heavenly afterlife and coming to terms with what his tie to destiny is or isn't. It's somber, funny, and bizarre. And gorgeous.

Hellboy (when done by Mignola) has always been a masterclass in comicbooking. His page design, his illustration, his tone balance, his writing. It's all nearly indistinguishable from perfection. Hellboy's concept is ridiculous pulp nonsense: a paranormal investigator who is actually from hell! But Mignola takes that and makes it not feel like pulp but Art and Literature. And as Mignola wraps the book with both a bang and a whimper, the reader will be forgiven for wanting to take it all in again as soon as possible. Sublime work.

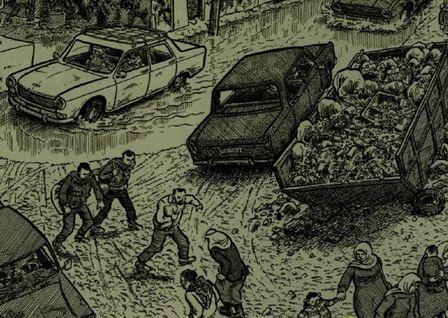

Akira

by Katsuhiro Otomo (translated by Yoko Emezawa w/ Linda M. York, lettered by Michael Higgins, colouring by Steve Oliff)

6 vols

Published by Marvel/Dark Horse/Kodansha

ISBN: 1632364611 (Amazon)

Akira is pretty much just legendary. One of those books that is so good that it ought to sit comfortably in the top half of any reputable Top 20 comics of all time list.

And it's not just one of those books that is lauded and recognized for its place in comics history. Akira is every bit as vibrant and jaw-dropping today as it was in 1989, when I first encountered it. That a book produced in the '80s should 30 years later still feel better and more accomplished than nearly anything in the last ten years is impressive, seeing as how we are essentially living in a golden age where every living artist can do pretty much whatever kind of comic they want.

Akira spawned an awe-striking animated film that basically turned the american sense of what animation could be on its head even though Akira the movie was a piss-poor adaptation of the glories found in Akira the book. (I remember wearing out my Streamline VHS tape back in 9th grade and it's still that dub that echoes through my mind whenever I remember scenes from the movie.)

Akira is about the leader of a teen biker gang that runs the streets of Neo Tokyo, a Tokyo that has arisen from the ashes of a terrible explosion decades earlier. It's about one of that leader's lieutenants who after an accident begins to develop powerful psychic powers. It's about how those unstoppable psychic powers, powers that make him a god, are nothing next to the powers of a kid who's been on ice for decades. It's about a city under military control. It's about politics and religion and annihilation and apocalypse and drugs and revolution and lasers and hovercraft and motorcycles and a guy who really just wants to spend some sexy time with this one girl terrorist.

When Marvel first brought Akira to the US, colourizing it and having Otomo redraw a couple scenes that wouldn't likely fly on American shores (like full frontal of a teen boy, redrawn to show him from behind instead), it was a revelation. If you are picking up Akira today for the first time, it will be a revelation. Last time I reread the series, it was a revelation—the book is so thoroughly a legend, so thoroughly a part of the comics canon, that it's easy to forget just how magnificent it really is.

Asterios Polyp

by David Mazzucchelli

344 pages

Published by Pantheon

ISBN: 0307377326 (Amazon)

Kind of like with the writings of Kazuo Ishiguro, reality, perception, and memory play a huge role in Mazzucchelli’s work here.

On top of this is layered the framework of Greek tragedy with specific allusion to the myth of Orpheus (this is pointed out through fistfuls of overt clues, not the least of which is a dream in which Asterios takes the role of Orpheus and his ex-wife Hana embodies Eurydice). We get narrative explanations from a meta-source in the Greek choral tradition. Comparisons to Dionysus and Apollo lead to an evaluation of dualistic systems (and perhaps systems generally) as Asterios gradually must free himself from systemic shackles in order to finally grow up. Of course we suspect if Asterios abandons one aspect he will be destroyed even as Orpheus was for abandoning Dionysus. As well, there are plenty of references to The Odyssey and readers will find this cross-pollination of mythologies only serves to enrich the experience of Asterios’ journey.

The subject matter, by its summary, sounds simple enough but Mazzucchelli throws so much into this piece and exercises such deft control over the page that one can easily drown in the details. The art is very particular. Much is made of Mazzucchelli’s use of colour through the book and, well, with good reason. The colouring itself offers storytelling that is available through no other means. In fact, so occasionally powerful is his use of colour that I worry for colourblind readers, that they might miss out on some of the book’s more sublime moments.

On top of Mazzucchelli’s tight reign over his colour spectrum, there is ample evidence that he maintains the same level of control over his linework and design. Asterios Polyp is a thoroughly designed experience, with every element from script to story to illustration to panel design to colouration to control of whitespace adding voice to the chorus of this performance. The battle between geometric and organic shapes gives readers (who may not be familiar with all the names and ideas Asterios or his ghostly narrator references) a hook on which to hang their interpreter’s hat. One’s experience of Asterios Polyp will no doubt be more enriched by a working knowledge of architectural history, familiarity with Greek mythology and Homeric tradition, and a smackerel of understanding of postmodern sculpture—but Mazzucchelli’s conveyance of story through his visual sense means that even those with Asterios-sized gaps in their education can still get in there and have some deeper sense of what’s going on.

Daytripper

by Gabriel Bá and Fabio Moon (coloured by Dave Stewart, lettered by Sean Konot)

256 pages

Published by Vertigo

ISBN: 1401229697 (Amazon)

Brás is occupied as the writer of obituaries and it is through this peculiar vantage that his own story unfolds. It is established early on that death is a part of life—perhaps largely so that we might get that out of the way and begin exploring what that precipitates in a meaningful way. Through the book’s constant return to the obituary, we are able to gradually piece together a philosophy of living, a valuation of lifespans. Moon and Bá present a carefully constructed yet simple meditation on what it means to be us and how life, death, and society conspire to bring meaning to the purposes we may invent for ourselves.

In trying to pin down the crowning achievement among all Daytripper’s perfections, I find myself struggling. There are so many wonderful things about this work that to attempt to elevate one above the others seems juvenile, a task for children who aren’t really concerned with absorbing the book for what it is. So then, I guess, let’s speak broadly.

First, the art that fills and wraps the book is just wonderful. Through the pen and the brush, Fabio Moon crafts a world that is wholly believable, one that holds as much life as the characters that inhabit it. The set designs are so varied and detailed and appropriate that it becomes easy for the reader to just pass by never considering the time and thought that went into planning these breathing environments. I would recommend all readers reserve an hour after finishing the book to just flip through the pages and take in the world of Daytripper without the press of narrative or dialogue or exposition or monologue hurrying attention on to the question of What Comes Next.

The degree of life invested in these characters and—specifically—into our protagonist is something special when one considers that we are only given ten short chapters with which to acquaint ourselves with those who comprise the world through which our protagonist explores his own life, purpose, and meaning. Well before the final page, he feels like a character fully revealed—as if, were the creators to free him from the shackles of the page, an attentive reader might be able to predict the course of his life. I feel privileged to have been allowed to take part in his life while he discovers its directions, purpose, and passions.

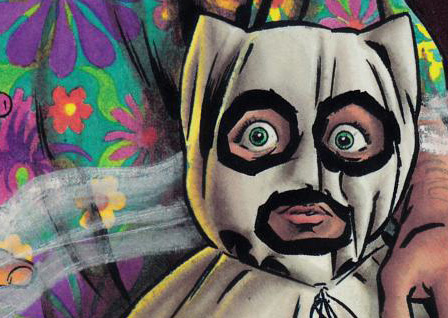

Building Stories

by Chris Ware

260 pages

Published by Pantheon

ISBN: 0375424334 (Amazon)

It’s entirely possible/likely that no one will have experienced the same story as I did when I read it or you will when you read it. The total possible number of different ways to approach Building Stories is 87,178,219,200 (or more than 87 billion, or 12 times the population of the earth).

Building Stories is a box. A box containing fourteen individual pieces of comics media of different sizes and dimensions. Fourteen stories, some hardbound, some in the form of pamphlets, some the size of newspapers (for those who remember newspapers). One was an 11"x16" folding screen, like a boardgame board. Another two were single pieces of quad-folded paper (like travel brochures), about as tall as the width of a business card but maybe seven inches in length. There is no prescribed, proscribed, or recommended order for reading these fourteen stories.

Ware’s protagonist (so much as there is one) is more like a full-orbed person and experiences both highs and lows. As well, her thought-life is robust. While she definitely does wallow occasionally in self-pity and a panoply of woe-is-me scenarios, she’s also thoughtful about social issues and the ethics of trivial actions. There’s even fleeting interest in questions of philosophy and theology. She is a woman built of hopes, recriminations, desires, disgusts, fears, joys, and a waxing and waning of drive. Much like any of us.

While Building Stories may not function so much as a traditional novel—offering a common Western narrative structure of beginning, middle, end—it does what it does very well. There is no overall build of tension, no climax, no denouement—but there was also never any pretension to such things. Beyond the impossibility of discovering The Correct Order in which to read Ware’s creation, his intention is less about unveiling a plot as it is about discovering a life lived. This is the life of the Woman, and by the end of it you will know her as well as you know many of your friends. She is undressed, not for your approval so much as for your empathy. This could be the closest many of us will come to walking in another’s shoes.

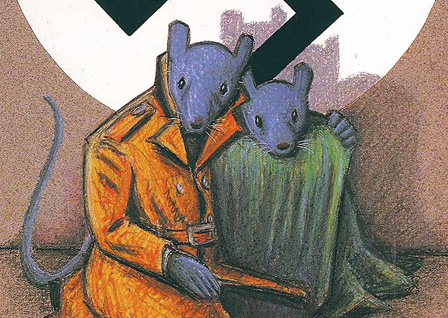

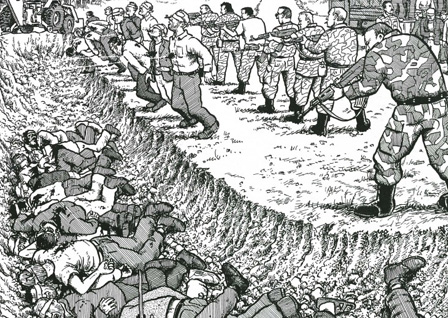

Berlin

by Jason Lutes

580 pages

Published by Drawn & Quarterly

ISBN: 1770463267 (Amazon)

Every now and again, a comic comes out that assures me that the medium can tell certain kinds of stories in a way that no other medium can touch. Every now and again, a comic comes out that despite its natural humility asserts itself as a model to which the medium should aspire. Every now and again, a comic comes out that just flat-out knocks me off my feet and makes me think that everything is going to be alright after all.

It’s not that Berlin presents such a rosie view of the panoply of human history. It doesn’t. It’s not that Berlin offers a solution to the din of political strife that will always wrack the tired bones of human society. It doesn’t. And it’s not even that Berlin allows true love to conquer even the dankest moments of our human despair. It can’t.

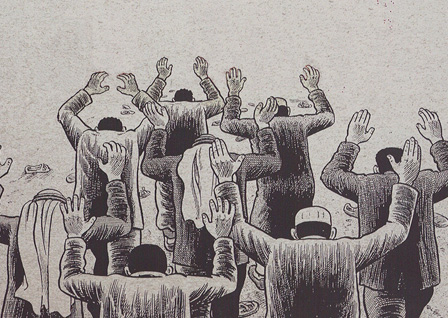

What Lutes’ book does, however, is demonstrate that creative geniuses still stalk the earth. His storytelling is virtuosic. And in addition to his mastery of the comic medium, Lutes proves himself an excellent student of the human state, capturing intricately the poisons that infects us all. Sure he depicts flawlessly the poor, huddled masses as they struggle to stave off starvation and fight for a political hope that will surely disappoint (as political hopes are wont to do), but further, he delivers too on the poisons that infect even human joy and celebration. We are given witness to ecstasy and abandon, but simultaneously, we also are allowed to see the darkness that threatens from the horizon, that in some sense has already crept into the lives of the happy.

And Lutes does this in such a way that he doesn’t come off as depressing so much as he does real. There is a veracity to his work that I cannot help but admire. As far as story direction, I didn’t like some of his choices for some of his characters. But they were always real choices. And I respect the story for it. And they set up well the story to come.

1–1011–2021–3031–4041–50

51–6061–7071–8081–9091–100

101-200201-300301-500Afterword

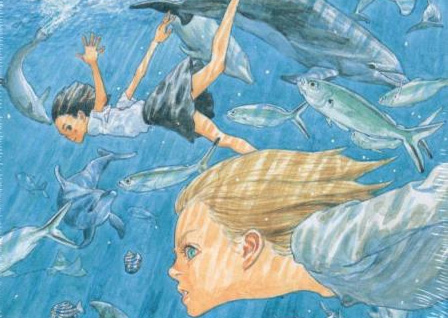

Children Of The Sea

by Daisuke Igarashi (translated by JN Productions, lettered by Jose Macasocol)

5 vols

Published by Viz

ISBN: 1421529149 (Amazon)

Here's something: I feel in greater connection to nature when reading Children Of The Sea than when actually out in nature itself.

Igarashi's work is specially known for his illustrations and treatment of the natural world. He is lushly reverent but his style is atypical, meaning it's difficult for a lot of readers to see the allure. He invokes wonder and mystery and makes that world holy.

One of the things I thought about last time I reread the short series was that as an artist par excellence, his every choice of line is intentional. He succinctly takes the chaos and scattered beauty of nature and concatenates it into a specific image, crafting a kind of paragon nature. This is why I may feel more connection to the natural in reading his works than when in nature itself. He conveys the grandeur and the majesty without the distraction of chaos.

(Or more accurately, without the distracting appearance of chaos. Think of your own hypothetical photos of Yosemite vs those taken by Ansel Adams. In reality we know that everything is governed by a towering compilation of causes and effects, but it's all just too complicated, so we call it chaos to make ourselves feel better, taking madness and submitting it under the thumb of taxonomy.)

I wanted to mention Children Of The Sea in this post simply because the books mean so much to me. Every time I read them, they impresses upon me more and more a sense of divine glory. I may see creation's majesty more in Igarashi's books than by any other venue. I'm averse to speaking in these terms because they are always either ineffectual at communicating or are baldly hyperbolic, but I find in Children Of The Sea this cascade of Sacred moments that I cannot get away from.

To further dive into terrible, deeply exaggerated cliche, it is in these five volumes that I find closest experience to the idea of Touching The Face Of God. In reading Igarashi, I feel as though I am Moses (for the literary or religious among you), hidden in the cleft, witnessing not God himself but instead the contrail of God's glory. Nothing else brings me as close.

And the great tragedy is that the book is so unique in its story and art that I rarely find myself able to recommend it because I know how rarely it appeals to anyone. And what is worse than saying that you beheld God's awestriking majesty, pointing someone else to it, and them having seen the exact same thing as you, saying, "Huh, he's not a very good artist, is he?"

In any case, these first images are a six-page sequence of the beginning of a rainfall and its transition to clear skies. I follow this with some scattered images of sea life.

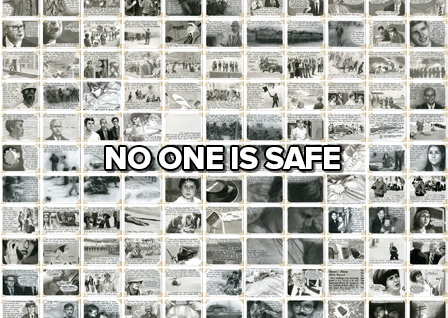

No One Is Safe

by Katherine Wirick

1 page

Self-published

Acquire it in digital here

No One Is Safe is an emotional work building its pathos on several foundations. It doesn’t as violently tear at one’s heart as, say, Twin Spica does, but in being modeled on real life, its agonies seem more present—even if of a more quiet variety. Wirick investigates the Kent State shooting, her father’s relationship to the Kent State shooting, and her own relationship to an ailing father. Her investment seems total. There are moments when the project looks as if it may be too much for her to bear. The reader knows this because as an interruptive narrator, she tells us as much; but these parentheticals, these hiccoughs, are not missteps in her narrative—indeed, the four or five panels in which she breaks from script and invites us into her experience of pain are some of the work’s defining moments. Not only are they abrupt breaks in the narrative chain, but they visually take a step away from the project’s principal conceit.

Wirick’s tremendous five-by-five-foot grid is composed of over 150 separate pieces of paper. They are painted on, drawn on, in such a way as to resemble the photographs we may remember from the ’60s—black and white with a quarter-inch of white border. These are fastened to her canvas with those little adhesive corner mounts that were common in all the best photo albums when I was four. Wirick’s three stories unfold and untangle and retangle across these “photographs” in a manner that is at once both practiced-and-careful and comfortably fluid. She appears in this work a confident author whose work deserves whatever attention you will afford it. And then she breaks her rules spectacularly.

The Arrival

by Shaun Tan

128 pages

Published by Arthur A. Levine

ISBN: 0439895294 (Amazon)

The immigrant experience isn’t the kind of monolithic thing that can actually be described using definite articles like “the.” It’s not as if every immigrant’s entry into a new culture follows a singular, well-trod path. The circumstances of each individual’s introduction to and incorporation into a new national heritage are as diverse and variegated as the expatriated themselves. Still, there are certain commonalities that often crop up in every new experience — every immigrating instance — whether moving from one nation to another or simply moving from L.A. to Seattle. Or taking a new job or attending a new school.

What Shaun Tan does in The Arrival — and does marvelously — is propose a cross-section of these immigrant experiences in such a way that even the reader who has never breached his own comfort zone might empathize. Tan offers to involve the curious into an experience that is confusing, disorienting, and alienating. That is, Tan wants to make us all immigrants for the space of his book. And he succeeds wildly.

The Arrival follows the experiences of a man who leaves his wife and daughter behind in order to pave a new path and new fortune for them in a land brimming with possibilities. He’s abandoned a country beset by grave ills but his road through his new home is anything but smooth. He does not speak the language, does not recognize the customs, and misses his family terribly. He is a man lost and Tan pulls the reader into his experience first by making the book silent, cutting all dialogue or narration. Then, mounting on this already sturdy platform of alienation, Tan introduces a world filled with bizarre contraptions, foods, sciences, and rituals — and then asks us shuffle along with his protagonist. It’s wondrous and frustrating all at once. We feel for the poor immigrant because if it’s hard on us (outside the book with no investment greater than personal interest), then it’s exponentially more difficult for him, with his wife and child and their survival on the line.

Silent comics have long struck me as a gimmick. None of the wordless comics I'd read seemed to use silence to any narratively purposeful end and in none of those cases was the story magnified by its lack of words. The Arrival is the first work I’ve read in which silence is essential to the experience. Tan uses the absence of dialogue, narrative balloons, or sound effects to propel his story and any verbal addition would doubtlessly hinder his purpose.

The Arrival is one of the very best comics experiences I’ve ever encountered and is well worth your time.

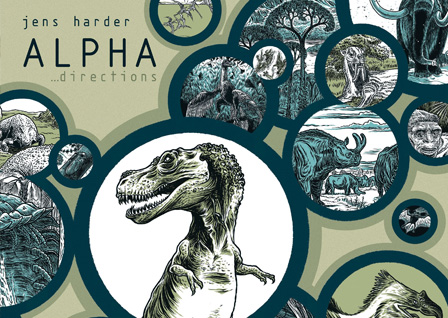

Alpha: Directives

by Jens Harder (translated by Nora Goldberg)

362 pages

Published by Knockabout/Fanfare

ISBN: 0861662458 (Amazon)

Alpha is a weird book. Or maybe not weird so much as maddeningly genius. It's part one of a proposed trilogy. Beta has already been released in German but Gamma remains only on the Potential horizon. It's too ambitious. Maybe it will never be completed but maybe it will. Fortunately, Alpha stands well on it's own.

Alpha presents the history of the earth from Big Bang through the cenozioc. Beta focuses on the rise of humanity from cenozoic to the present day. Gamma will tell the history of the world from today til the end of the universe. Where these books are unique is in the methodology.

Harder tells the story of the world through borrowed images. He came up with nothing in the book on his own. He drew everything, sure, but it's all redrawings of other things—from scientific illustrations, to illuminated manuscripts, to ancient maps, to sculptures, to comics and other pop cultural ephemera. You'll see things in panels in the pages I post that you recognize. Maybe it's Tintin, maybe it's Godzilla, maybe it's Goya's Saturn. The book, by its method, holistically draws from the whole of human history and experience and belief to make the story of creation our story.

Equinoxes

by Cyril Pedrosa (translated by Joe Johnson, lettered by Ortho)

336 pages

Published by NBM

ISBN: 1681120801 (Amazon)

Equinoxes juggles the lives of about ten characters in France across the four seasons and ending in Summer 2002. Many of these lives are only tacitly related, interacting only glancingly at perhaps a single point in their histories. There are connecting threads, of course. A prospective airport and the mild political unrest it causes, a minister of the environment, a painting in a cave, a painting on a canvas, a handful of songs, and (most presently) a young woman with a camera. One of the principle characters remains obscure throughout but her fascination with an old camera gives the reader a window into many souls—every time she takes a person's picture the comics form is interrupted by the intrusion of a prose investigation of the captured individual, as if we're getting a sense of that person's conscious and subconscious self in the precise moment of the camera's click.

Apart from this particular conceit, the book also develops visually through the four seasons, with each being marked by a distinct alteration to the style of illustration. Either idiosyncrasy would be a fascinating aspect for Equinoxes to engage, but when taken together along with the superlative writing and thoughtfulness to the book, it becomes clear that Pedrosa's book is something special—and why it was my choice for best book of the 2016.

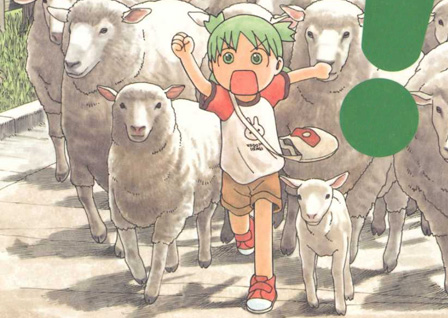

Yotsuba&!

by Kiyohiko Azuma (translated by Javier Lopez/Stephen Paul, lettered by Scott Howard?/Terri Delgado/Abigail Blackman)

13+ vols

Published by ADV/Yen Press

ISBN: 0316073873 (Amazon)

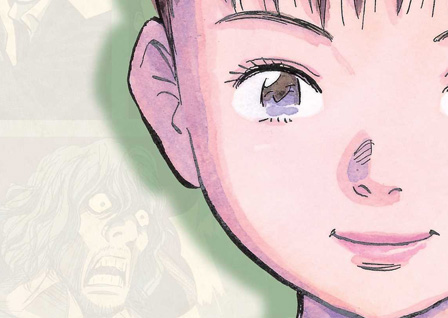

Yotsuba&! is a source of deep magic for me. And, I suspect, for a great number of others as well. Kiyohiko Azuma’s series is an unexpected pleasure. Even if one approaches the work with the knowledge that Yotsuba&! bubbles forth as a fountain of joyfulness, this little girl’s nature and adventures will still surprise in how purely they deliver one into this momentary Other Place.

Four-year-old Yotsuba’s sense of wonder in the way she approaches an environment with which she apparently has had no experience is astonishing in its guilelessness. Yotsuba brims with enthusiasm and the pleasure with which she takes on each new experience leaves us breathless as that enthusiasm spreads. Her father is consistently amused by her naïveté and her neighbours are never certain what exactly to make of her. And yet, she really does inspire affection in everyone she encounters.

My descriptions can only serve as a diminishment to what pleasures are actually found in the book. I am entirely out of my depth to sound out Yotsuba&!'s charms, but perhaps we should just leave it at this: whenever a new volume arrives in the mail, I curl up comfortably with my wife, finding the best lighting possible under such snuggly conditions, and I read each chapter to her aloud, trying to muster in my own voice the clear enthusiasm in Yotsuba’s own.

And then we both smile a lot.

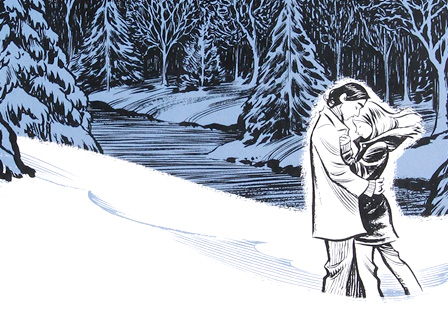

Blankets

by Craig Thompson

592 pages

Published by Top Shelf/Drawn & Quarterly

ISBN: 177046218X (Amazon)

There are any number of reasons that Thompson’s work should be lauded. His art is gorgeous and his brushline expressive. He treats personal topics with a sense of both whimsy and honesty. He writes true experiences, even when they’re fictional. And as great as all those things are, there is one idea that stands out in his work that I’ve yet to see another creator tackle (let alone master) as Thompson has done.

His sense of the sacred and his ability to convey it in ink is breathtaking. He offers his readers these holy moments, these frozen, fluid, organic treasures. These sacramentals. Whether he intends to lead the reader into a religious experience or not, his work really is very spiritual. As spiritual as an atheistic holy experience can actually be at any rate. There may be moments in Miyazaki that approach the wonder of the sanctuaries that Thompson builds in Blankets. It’s for this reason (among others) that Thompson’s second book remains one of my favourites, even years after having first encountered it.

Semi-autobiographically chronicling (via chrono-thematic structuring) his early life—from his establishment in faith and his discovery of love to his abandonment of that love and his subsequent abandonment of faith—Thompson plays honestly at all times with his story elements, thereby lending his tale an uncanny credibility. And while flashbacks and tangents proliferate, the overarching chiastic structure verifies the reader’s intuition that Thompson knows well where he is headed and is going to take you there whether you like it or not.

This book is a masterpiece of form, symbol, and structure. Tokens bend and writhe and carry narrative significance throughout. Thompson’s art here is fluid and serves well to establish the variety of moods described in his several vignettes. Blankets is an evocative work that should not be missed by any who would appreciate a serious, heartfelt, and magical telling of the tragedy and wonder of what it means to come of age.

Sunny

by Taiyo Matsumoto and Saho Tono (translated by Michael Arias, lettered by Deron Bennett)

6 vols

Published by Viz

ISBN: 1421555255 (Amazon)

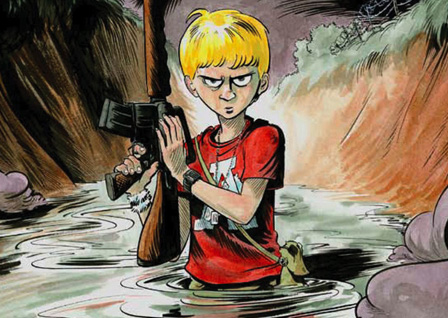

Sunny is about a collection of kids interred at Star Kids Home in the late '70s. Some of these kids are straight orphans, some have parents who want them but can't support them, some have parents who just can't be bothered. The series is amazing and one of the best things going.

Matsumoto's evolving series of pericopes peeking in on the lives of the residents of a late '70s foster home is at once vital, brooding, joyous, grim, and heartfelt. It may be the perfect encapsulation of the human condition. And amazingly, the series improbably improves with each volume. In 2015's volume 5, I feel more and more the need for the series' finale in volume 6 to provide some sort of "20 Years Later" epilogue—if only for how crisply and seamlessly these characters have been brought to life for me. My heart pulls for these kids—and for the adults who mind them. With every victory I soar and with every defeat I sorrow. I can think of no better compliment than to say that Sunny is one of the most honest, affecting works I've encountered. I love that this exists and I love the care with which Viz has packaged it.

Ordinary Victories

by Manu Larcenet (coloured by Patrice Larcenet, translated by Joe Johnson, lettered by Ortho)

2 vols

Published by NBM

ISBN: 1561634239 (Amazon)

Ordinary victories is an extraordinary book. It's rather simple on the face of it (a young photographer with panic attacks struggles to socially adapt to life that isn't on his terms) and by setting and dialogue becomes something great. While dealing with Marco's neuroses and the will he/won't he of whether he'll have a successful relationship (with his parents, with his brother, with his girlfriend, with his neighbours), most interesting to me was the book's exploration of the question of separation of art and artist when one or the other sucks. Who deserves our scorn? And how scorched earth should we be in the application of that scorn? How much do our convictions matter? How much do we martyr ourselves?

As the moral detritus of so many artistic heroes finally begins washing up and we see more incisively how terrible some of our most creative minds truly are or were, these questions will be more and more central to the average person's consumption of art.

Three Shadows

by Cyril Pedrosa (translated by Edward Gauvin)

272 pages

Published by First Second

ISBN: 159643239X (Amazon)

Three Shadows, for all its heartbreak, really is a wonderful work. Pedrosa’s art is dynamic and assured, balancing a deep naturalism with necessary storytelling chops. I want to see more of his work and I want to see it now. His visual sense more than compensates for how little dialogue wanders through his book. Certainly Pedrosa uses words, but more often than not, he simply uses his pagework to bring texture and life to his story about death.

Any work about such a darkly emotional topic will find itself hounded by one great threat: the danger of becoming a cheap, sentimentalist ploy. A full ninety-three percent of movies about dogs fall into this trap. Easy manipulation. Contrived heartbreak. Formulaic beats. As Hollywood shows us at least yearly, hammering on heartstrings to get a reaction and jerk some tears is child’s play for even incompetent writers. Pedrosa could have gone this route and let his artwork trick us into thinking we were reading something great and whelming. He, fortunately, is better than that.

Pedrosa’s book balances between whimsical, fantasy elements and the darkness of real-world tragedies, delivering something closer to a meditation on impending loss than a critique of how one might deal with such an inherently counter-rational experience. Despite its subject matter, Three Shadows never threatens to be more than one can take. If anything, its lessons are delivered gently and with deep empathy.

1–1011–2021–3031–4041–50

51–6061–7071–8081–9091–100

101-200201-300301-500Afterword

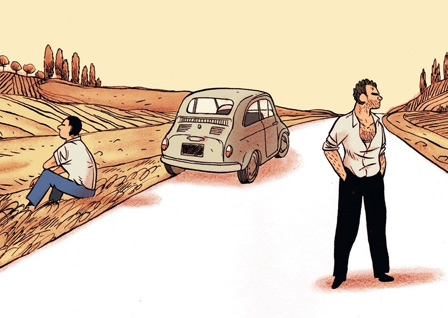

Come Prima

by Alfred (translated by Studio Charon)

224 pages

Published by Delacourt

Buy digital: (Kindle/Comixology)

Come Prima is a fairly simple story (in the, say, '60s this guy with an urn goes to pick up his estranged brother and take him back from France to Italy in a beat-up old car and maybe they'll talk it out on the way), but the way it makes use of the form is superlative. And not superlative in that possibly pretentious sort of way a lot of would-be masters engage. This stuff is natural, organic, perfectly at home with the lazy sort of human chaos that inhabits the story being told.

Dialogically this work is grounded and earthy, but visually Alfred gives us raw lyricism and beauty. I fell in love with this book early on. Highest recommendation. But only avialable in English on Comixology.

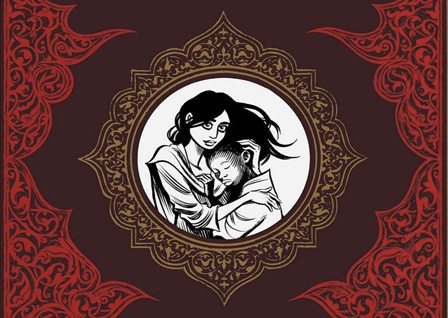

Habibi

by Craig Thompson

672 pages

Published by Pantheon

ISBN: 0375424148 (Amazon)

Through a work criticized both for its Orientalism and its skirting of misogyny, Thompson balances several themes throughout Habibi's unfolded history of two runaway slaves, but perhaps chief among these is an exploration of love, of true love—and how it can exist, flourish, and grow even (and sometimes especially) in the absence of sexual fulfillment. Some authors focus on women as pure objects, as receptacles for sexuality to the exclusion of their ability to exist as full-orbed human persons with dreams, hopes, loves, or even (for the most part) personalities; Thompson, on the other hand, uses the objectification of his characters to craft them into noble persons deserving of dignity, of hope, of love. It's a fine line and your mileage may vary on how successful you think Thompson is at walking it.

Habibi is a major work in comics literature and Thompson’s first since the nearly-six-hundred-page Blankets. Comparisons will be obvious. Both works traffic deeply in religious language and colour their texts in displays of sacred ferocity. Both explore the boundaries and need for love and human contact. Both play with non-linearity in storytelling, skipping back and forth and only revealing the past in time to illuminate the future. These two creations are very much the work of the same author and it’s a joy to see his voice maturing.

In both tone and scope, Habibi is an entirely more ambitious work. We see Thompson redressing things that were focal points in Blankets. In the former book, Raina is depicted in such sacred light by Thompson that she becomes the ultimate example of female sexual objectification—all with the best intentions of course, but when young Craig deifies her, he makes her into little better than a graven image. In Habibi, however, when Dodola is depicted nude (which is often), she is wholly human. This is a triumph of Thompson’s technique, for in the midst of the narrative she is being wholly objectified, yet these instances serve only to drive home her humanity. For the majority of those within Habibi's narrative landscape, Dodola exists much as many men's ideal woman—she is merely a receptacle for their sexual advances. Thompson, however, prevents the reader from seeing her in this way by refusing to give her the visual lyricism he bestowed upon Raina. Both are sacred and both are holy, but the one is made so by her sexuality while the other is made so by her personhood. It’s a difficult line to draw and that Thompson illustrates it so well ably demonstrates why he is one of the leading auteurs in the medium.

Habibi is a book marked by rape, slavery, castration, forced marriages, the murder of children, harems, and love. While in its murk and depths, it may not seem possible that the last of these—love—should so completely over-power all else, this is the case. Love is not always victorious, but it is always glorious. The love of these two for each other is simultaneously heart-rending and heart-warming.

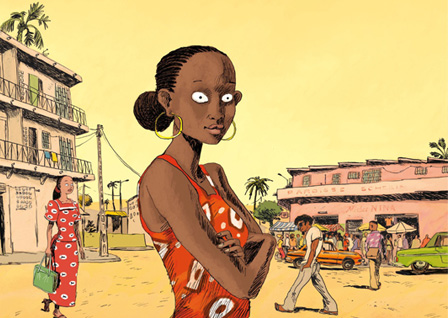

Aya: Life In Yop City

by Marguerite Abouet and Clement Oubrerie (translated by Helge Dascher)

2 vols

Published by Drawn & Quarterly

ISBN: 1770460829 (Amazon)

Aya is one of the coolest things. Taking place in Yopougon (colloquially known as Yop City), a suburb of Abidjan in Côte d’Ivoire, tells more than the story of Aya and her friends, acquaintances, rivals, and relations. On top of that, it unveils a culture unique to a 20 year period and now lost to that era in history.

Between 1960 and 1980, Côte d’Ivoire thrived economically in a way that other newly independent African nations did not. Rather than drive out European populations and influences, those ties were welcomed and strengthened—and the wealth and assistance of France helped the economy boom in particular ways.

Aya exists in the US as two volumes, each containing three of the original graphic albums in which the series originally appeared. Aya is about 20 years old, single, beautiful, wise, naive, and soberminded. This story features Aya, yes—but they also tell the stories of Bintou and Adjoua and Hervé and Moussa and Félicité and Mamadou and Innocent and Gregoire and their families and more. It's a multi-multi-threaded narrative that's rambunctious and cacophonic and really is a blast to read.

The book is filled with people making bad but very human decisions, the kinds you or I make and have made regularly through our lives. It's also filled with proverbs. One of the idiosyncracies of life in Cote d'Ivoire is that every is constantly using old proverbs to make points, comfort the abused, and perpetrate savage burns. And everybody nods in understanding as if the speaker just QEDed the whole thing and shut it down. (And it's very amusing when one of the cast goes to France and does the same thing and these poor French people have no idea what's going on.)

While the storylines of Aya can get pretty serious (a guy basically selling his daughter into marriage, coming out of the closet in a culture where that would be dangerous, fake faith healers, rape and sexual assault, adultery, adultery, and more adultery, etc) the wit and barbs and lunacy keep the spirit pretty light-hearted.

One last thing I love about this series is that it doesn't preach or go in for didacticism. It 1) knows that people are people and will do good and bad things, often on the turn of a dime, and 2) presumes the reader intelligent enough to draw their own conclusions. So, for example, when Bintou comments on the rapist's poor looks wonders what gives the him the right to rape so many girls and then comments that "handsome helps," citing a girl who was raped by a cousin and made the best of it, Aya's response of "That's terrible!" is more focused on Bintou (who runs an advice/counseling business) betraying a confidence than on the woman's opinions about rapists (and we already know that Aya doesn't agree with her). It's just one example of hundreds in the book of normal people holding wonky opinions, just like in real life. In a period where a lot of our fiction reads as pedagogy, it's kind of refreshing to run into something that doesn't pull a GI Joe where "knowing is half the battle."

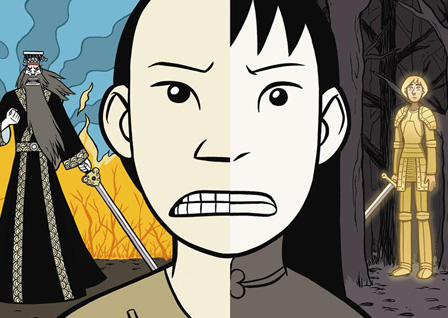

Lastman

by Balak, Michael Sanlaville, and Bastien Vives (translated by Alexis Siegel)

12 vols (only 6 translated into English)

Published by First Second

ISBN: 1626720460 (Amazon)

Last Man is pretty easily one the most exciting series published in the last decade. Beyond being lithely and gorgeously illustrated by Sanlaville and Vivès (Vivès did A Taste Of Chlorine, which I mentioned a few posts back), the story is pulse-poundingly exciting. What begins as a magic fighting tournament in a rather fantasy realm turns into a cross-dimensional adventure when a theft speeds the recently arrived outsider Richard Aldana out of town in a hurry. Young Adrian and his mother give chase and things get out of hand real fast.

And the result is compulsively readable.

The artists portray so much elegance of motion that even heavy, stomping, oxen men move with a kind of liquid energy. Certainly more like a crashing wave than something more gentle, but still. More lithe figures like Adrian exhibit the same sense of weightlessness as the dancers in Vivès earlier work, Polina. The backgrounds, too, are skillfully devised with all manner of unexpected detail. A dragon here, a crowd reaction there. Altogether lovely.

But even better than that—and if you can imagine for a minute the essentiality of fluid combat choreography for this kind of story and then consider that this is better than that—the illustrators hold utter mastery of the characters’ expressions. Their faces are simple but convey a wealth of intents and meanings. Child protagonist Adrian shifts from guileless to guarded to curious to excited to determined to overjoyed, and the purpose behind his countenance is never in doubt. Richard Aldana also modulates between a host of feelings and moods and interests. There is, at all times, the overt story being told through dialogue and action, but simultaneously there is another story told across the faces of this book’s participants, a narrative born in looks and in eyes and in mouths and in shoulders and in the space of physical proximity, one character from another. This is a rich tapestry and this trio of creators demonstrates mastery of all the elements of their stage.

A valid question right now for the US reader is Is it worth it to jump onto a series that publication woes have placed in indefinite limbo? The series is 12 volumes long but it may be that in the US we will only ever get translations of the first 6 volumes. I'd say a guarded, Yes, that it's worth it. Even though vol 6 does end on a pretty cataclysmic cliffhanger, it also wraps up pretty decisively the first major arc of the series and in that sense feels mostly complete. It's not a great feeling to be left hanging with only 50% of the series but that 50% is so well done (despite occasional missteps) that I'd happily recommend the series to any adventure-lovers with the caveat that they know going in that they're reading an incomplete work. [Really, what I'd love is for entire series to be published in four oversized omnibus editions like the Hellboy Library Editions, to give the series its due.]

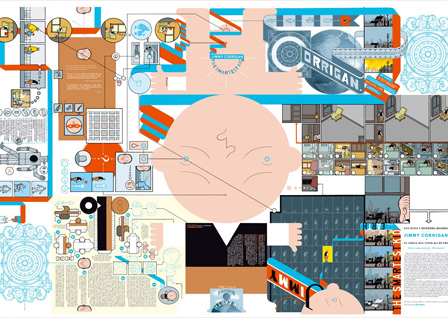

Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid On Earth

by Chris Ware

380 pages

Published by Pantheon

ISBN: 0375404538 (Amazon)

I don't often talk about Jimmy Corrigan because it's pretty thoroughly enshrined in most versions of the comics canon floating around out there (note: there is no canon). Still, it's one of those books that's highly regarded but not nearly so accessible as Watchmen (yay! superheroes!), Maus (dang! Holocaust), Persepolis (yay! little girl rising up against a repressive regime and not dying!), the usual answers to the question: What should I get for my mom/dad/boyfriend/wife/etc to prove the value of the medium? (I mean, unless you're just gonna go with super-popular0-but-for-adults-because-boobs-and-eff-words, i.e. BKV.)

Jimmy Corrigan would probably play well with a lot of serious grown-up types except for the fact that 1) for the neophyte comics reader, Ware can be friggen impenetrable, and 2) Jimmy Corrigan is, for all it's imagination and flights of fancy, a sad sack of mopey living to read about. It's not, for those reasons, super appealing.

So I'm going to recommend it to you. For a couple reasons.

1) It's formally astonishing. People marvel (and rightly) at how intricately Alan Moore plans and executes his pages in Watchmen—and for sure, that's Watchmen's strongest point. Moore is diabolically exacting. Any halfway worthwhile annotation of the series will unveil that for you. But to me, compared to Ware, it feels like Moore is putting together a 250-piece puzzles of the United States while Ware's just laid the final piece in a 2000 piece jigsaw of the colour red. Watchmen impresses me but Jimmy Corrigan blows my mind. I don't know how he does it. He's so intricate, so exacting, so methodical. (And ironically and sensibly, this magnificence is a put-off for some, rendering his work sterile and over-produced.)

2) He outlines pretty handily a particular kind of person. And depending on who you are, who you know, and your life experiences, this may be revelationary or shrug-worthy. Personally, I don't know anyone who is remotely like Jimmy. Maybe you do. Maybe you know a lot of them. But for those of us who don't, Jimmy is a rigourous peek into a way of living, of thinking, of interacting that we might not otherwise be able to grok. It's unclear exactly how much of Jimmy is autobiographically considered, but from Monograph, it seems like despite whatever similarities exist, Jimmy really is his own persona. And one that the reader well inhabits by story's end.

3) Ware is not only telling the story of Jimmy. He's not only telling the story of five generations of Corrigan men. He's telling a story of Chicago. And when the book takes an extended holiday into the past, Jimmy's story is made so much richer for the excursion. When Brubaker zips back in time in Fatale, it's a neat trick and we see some fun stories, but ultimately it doesn't really matter and the story would be as worthwhile without the flashback. In Jimmy Corrigan, the reverse timeskip is essential. The book would be a hollow shell without it. (Haha, some will argue it's a hollow shell anyway.)

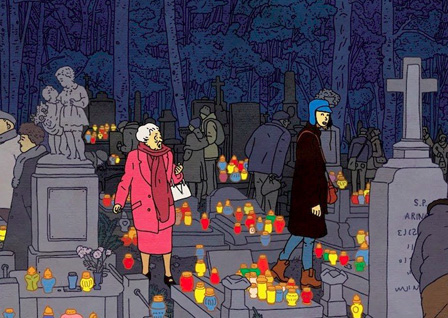

The Property

by Rutu Modan (translated by Jessica Cohen)

168 pages

Published by Drawn & Quasrterly

ISBN: 1770461159 (Amazon)

[Note: If you're looking for a serious literary-fiction graphic novel for a grown-up (say, your mom) to prove the value of the medium, this is probably a good starting point for you (her).]

Ruto Modan’s The Property, for all the many things it is, most interested me in its exploration of both of Linklater's earlier Before movies’ themes through its two female protagonists, grandmother Regina and granddaughter Mica. Modan almost certainly does not actively seek to explore the two films—she may not even be aware of them—but the nature of her characters and their stories puts the Linklater films strongly in mind. The titular property is never quite MacGuffin, but it may be close enough. Whatever the case, the property in question gets twenty-something Mica to visit Warsaw with her grandmother, where she meets a young man. A probably nice young man. The property also gets almost-ninety-year-old Regina to visit the city for the first time since fleeing (while pregnant) under the shadow of the Reich. It’s a visit haunted by memories of the lover she left behind. The property does have its place in both motivating story elements and drawing things to their open-ended conclusion, but this is a story of persons interlocking and intertwining rather than any sort of real-estate thriller.

And while Modan crafts an entirely enjoyable story for the younger Mica, it’s in Regina’s life and reaction to Warsaw that The Property was most fascinating to me. Jesse and Celine probe their frustrations and disappointments in Before Sunset, considering what might have been and how time both dissolves what was and erects new burdens (as well as mythologies)—but they’re still young and only what, thirty-one? Regina interacts similarly in her own homecoming—only where Jesse and Celine have decades of potential joys and mistakes ahead of them, Regina at nearly ninety has little time left. She may be spry enough to travel, but illness lurks and too often our elderly are taken by nothing more powerful than the common flu. And that pointed fragility makes a vast difference in the way one will regard their dreams and their future. (An abiding and important theme throughout is Warsaw-as-cemetery. It’s on the book’s cover. It’s mentioned in the opening pages, and the climax takes place in the grand and sprawling cemetery.)

Young Frances

by Hartley Lin

144 pages

Published by AdHouse

ISBN: 1935233424 (Amazon)

It took me forever to get on the Pope Hats train. I was even at the Small Press Expo the year it won an Ignatz, but left without purchasing. A big part of my reluctance is that I don't really have a viable means of storing saddle-stitched work. I have shelves that are good for stuff with spines where you can read a book's title, but nowhere to keep zines or periodical issues. But like, who cares, really, right? What's important is that I did end up getting all five issues of Pope Hats—and ended up as smitten as everyone else.

And then, like two weeks later, they announced a trade paperback edition. Oh well.

Young Frances is very good at what it does. It tells the story, principally, of Frances Scarland, who begins the series at the low rung of the law firm totem pole but gradually begins to climb, almost accidentally, through no ambition of her own. It's the story of her and her best friend Vickie (an actress) and the friends like Peter who enter their orbit. It's the story of pretty real feeling people living pretty real feeling lives. It's comfortable and enjoyable and relatable and pretty much perfect. I'm glad I'm on this train now. You should get aboard too. Choo choo.

Little Nemo

by Winsor McCay

Newspaper serial

ISBN: 383656310X (Amazon)

More than a century ago, WInsor McCay was visually and formally blowing the socks off comics that would be produced a hundred years later. The man was visionary in a way that actually merits the term. His use of colour in a newspaper strip is astonishing. As a colourist, he would wow even today. His page layouts were wild and exploratory. He's positively rabid with talent.

He also (dammit!) enjoys the racial privilege common to the Euro/American caucasians of his era, depicting black analogues (and in Rarebit Fiend, actual blacks) in the Sambo-esque manner of white cartoonists and illustrators at the turn of the 20th century. It's a mar on his work and character; it angers me that someone so clearly imaginative would not be able to imgaine his way into a better sense of black humanity.

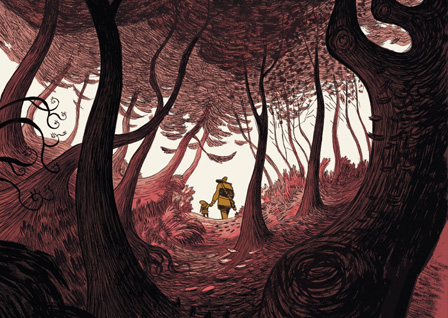

The Summit Of The Gods

by Jiro Taniguchi, based on story by Baku Yumemakura (translated by Kumar Sivasubramanian)

5 vols

Published by Fanfare/Ponent Mon

ISBN: 8492444401 (Amazon)

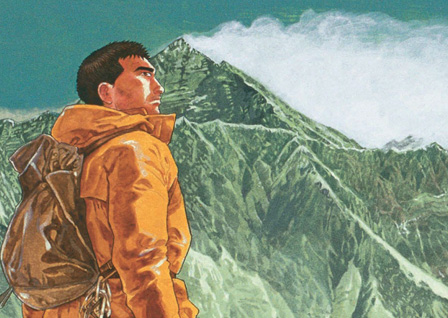

I know nothing about mountain climbing and care little for the sport. While I’ve backpacked a bit in the Yosemite backcountry (up around Hanging Basket at about 3000 meters) and Kings Canyon (over Lemarck Col at nearly 4000 meters), I’ve never actually taken to climbing at all. I had several friends who were into rock climbing out at Joshua Tree, but it just never appealed to me. Around 2002, I had a roommate who was an honest-to-goodness mountain climber. He and his partner were aiming to be the first black men to scale the Seven Peaks. Everest was one of those he hadn’t yet tried, but it was on the list. Still, for all that—after seeing all his gear laid out, seeing photos of him cresting the heavens, seeing the charge he got as an expedition approached—I never caught the bug. Not to climb and not to spectate.

I probably just needed a narrative. I probably just needed The Summit Of The Gods. Because this book. Oh, man. It crawls into your soul. You know that scene in Luke Pearson’s Everything We Miss where the shadow creature wends its way through the guy’s head and neck and pries his mouth open and waggles his tongue so that unbidden he says terrible things to his girlfriend? The Summit Of The Gods is similar but instead of playing at cruelty with your words, this thing snakes deep within you, grips your heart’s heart, and ignites your very soul. For the space of my involvement within the pages of Taniguchi’s adaptation of Baku's mountain-climbing epic, I am wholly theirs—and deeply enamoured with Everest and K2 and whatever other peaks they want to throw at me.

I could not have expected this. I was so excited, so thoroughly overwhelmed, that I almost did not want to read anything else for some time after. I didn’t want to pollute the holy sacrosanctity of the experience Baku and Taniguchi provided.

While principally interested in a particular climber and his alienating pursuit of an impossible ascent of Everest, Summit Of The Gods has more ranging interests as well. In order to build suspense and appreciation, much of the first three volumes of the series is built around the recollections of a handful of climbers as they recount to an interviewer past climbs, records, and disasters. These remembrances are fascinating, thrilling, and haunting. Some of this is heart-racing, life-and-death stuff. Especially invested readers may find themselves slightly exhausted as episodes close and the narrative moves to the next foundational piece of Summit's puzzle.

Calvin And Hobbes

by Bill Watterson

Newspaper serial

ISBN: 0740748475 (Amazon)

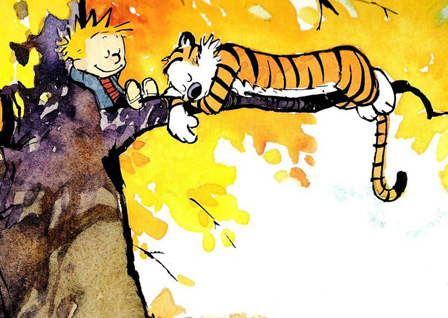

Calvin And Hobbes landed when I was 12 years old, a couple months into my sixth grade year. At the time, my mornings were ritualistic. I'd wake for school, creep out into the living room with a bowl of cereal, the LA Times, and a blanket. I'd use the blanket as a tent and sit over the heater vent, ballooning that tent, and read through the funnies while munching down Crispix or Product 19 or Crispy Wheats And Raisins. I loved that time. It was mine and it was sacred. And then suddenly this new strip appeared about a boy and a stuffed tiger and it was like a warm Autumn light was burbling up out of the page.

I always had a stream of favourites—Mister Boffo, Pluggers, Shoe, Mutts, Non Sequitur, Bizarro, and The Neighborhood—but, man, for the eleven years it ran, Calvin And Hobbes was the light of my life. As an adult, I'm less entranced by the content (which remains smartly written) but when I look at Watterson's artistic choices, I'm often floored that this talent was gracing the daily newspaper on the funnies page.

It also made me pity NY Times readers.

1–1011–2021–3031–4041–50

51–6061–7071–8081–9091–100

101-200201-300301-500Afterword

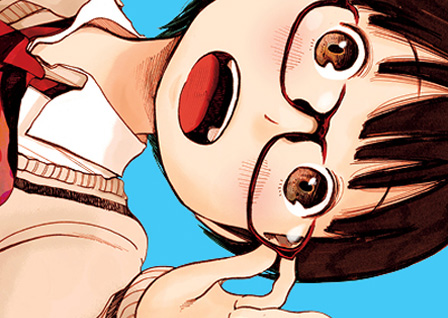

20th Century Boys

by Naoki Urasawa (translated by Akemi Wegmuller, lettered by Freeman Wong)

24 vols/12 vols in new Perfect Edition

Published by Viz

ISBN: 1421599619 (Amazon)

There are moments in history that are more important than others. Not in themselves, not in their significance on their own merits. These moments are notable in that they trigger more cataclysmic events years later. And they are genuinely interesting because the true weight of their value cannot be discerned in the moment of their occurrence.

Naoki Urasawa’s 20th Century Boys is a work founded on such moments. Part of Urasawa’s thesis seems to be that while one can never tell what will result from his or her actions, it is also impossible to discern which actions will have far-reaching implications. What could bring about the end of the world: The Apollo moon landing? The 1970 World Expo held in Osaka? The destruction of a child’s fort? A chance encounter? The theft of a trinket? The discovery of a haunted house? The playing of an obscure American rock song on a junior high school’s PA system?

20th Century Boys is a sprawling, complicated work. It’s all over the place. Its plot spans from the Apollo moon landing of 1969 to the near-future of 2018. Its narrative bounces back and forth between a robust and ever-expanding cast of characters—even while skipping all over its own historical scope, sometimes through flashback and sometimes through a particular sci-fi conceit. Yet through it all, Urasawa never abandons his exploration of Today having been built on the bones of Yesterday.

For all his story’s complexity, Urasawa is always certain to give the reader plenty of historical hooks to help us keep our bearings. References to cultural phenomena abound. From raw historical notes like the 1969 moon landing and the 1970 Expo to related cultural realities (such as the proliferation of salesmen hocking “NASA-approved” pens, foods, and other ephemera). Urasawa especially excels at noting pop cultural artifacts that boys of the ’70s would have remembered: wrestling stars! manga! anime! These were every bit as essential to the cultural landscape of Urasawa’s cast as the Atari, Wolverine, MUSCLE men, Transformers, and “We Are the World” were to my own. These things ground 20th Century Boys in a real world so that when things start going crazy, readers will at least have a foothold to rely upon before the ship begins to sickeningly sway.

Principally, 20th Century Boys concerns a group of friends and how the club those friends formed as children in 1970 somehow laid seed for a cult that would try to take over the world. Twenty-five years later, a virus that causes the human body to expel its blood is released and the Friends cult may be responsible. Kenji, one of the two former leaders of the group recognizes that the virus and some other things line up with the Book of Prophecy he and his friends developed in their secret hideout. What was once a story of crude, cliche-ridden heroism has seemingly become a reality. It’s up to Kenji to discover the identity of The Friend and stop his cult from destroying the world.

Or something like that.

Ooku

by Fumi Yoshinaga (translated by Akemi Wegmuller, lettered by Monalisa De Asis)

14+ vols

Published by Viz

ISBN: 1421527472 (Amazon)

Would highly recommend the series Ooku: The Inner Chamber. It's an alt-history of Japan. During the third shogunate (what, around 1625 or so?) the country gets swept with the red-face pox, a pox strain that Y-The-Last-Man-style only affects males. Only 20% of the male populace survives so society (and even the shogunate) switches to a female dominated life and governance.

The cool thing is that despite the switch, Japanese history is essentially unchanged. All the shoguns and all their stories and all the Japanese events remain unchanged save for that now it's women in the same roles. So you're getting this amazing story that is basically just a trick to get you to read Japanese feudal history and think about women outside their traditional roles. And it's amazing.

And there are some seriously deeply Machiavellian nuttos up in this thing. Poisonings are rampant. Scandals, beheadings, coups, maneuvering, jockeying heirs, the whole shebang. It's madness and you want so badly for some catharsis and for the villains to get theirs. And sometimes you get that but a lot of times the bad guys just win and never suffer a single consequence.

And the crazy thing? All of this really happened—because Yoshinaga is just telling you the story of Japan.

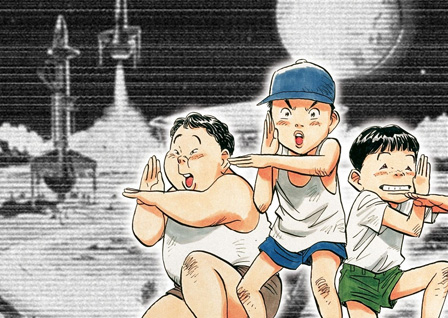

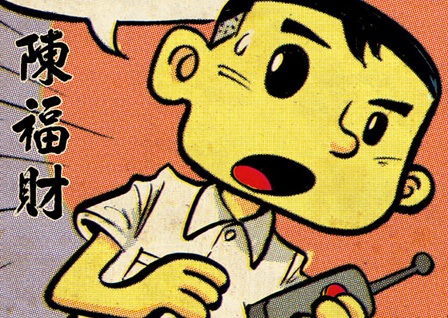

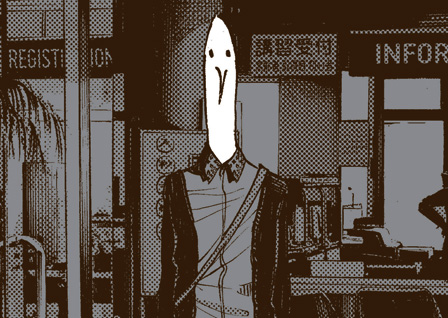

The Art Of Charlie Chan Hock Chye

by Sonny Lieu

320 pages

Published by Pantheon

ISBN: 1101870699 (Amazon)

This book is a marvel and ingenious.

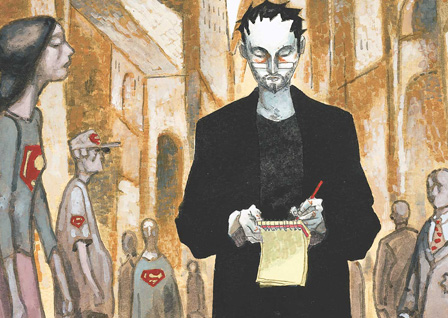

Sonny Liew’s graphic novel masquerades as a retrospective collection of the life’s work of Singapore’s greatest cartoonist, Charlie Chan Hock Chye. In truth, there is no such artist, and the book is instead a roundabout way for creator Liew to unveil a counter-narrative to the Singapore Story, the official explanation of Singapore’s path to independence and success. Liew’s examination of Chan’s comics across the decades brings light to the less-than-shining moments of Singapore’s recent history and the policies of Lee Kuan Yew and lost an art grant from Singapore’s National Arts Council for his trouble. A fantastic example of entertainment as more than entertainment; also a nice, brisk introduction to the island nation of Singapore.

Dorohedoro

by Q Hayashida (translated by AltJapan Hiroko Yoda and Mat Alt, lettered by Kelle Han and James Gaubatz)

22 vols

Published by Viz

ISBN: 1421533634 (Amazon)

I don't even know what to write here. Dorohedoro is wrapping up and if you're already this far in then of course you're in for penny and pound. If you haven't yet tried the book, give it a shot please (if you can handle blood, violence, and comedy). It's one of the most creative books I've ever encountered. I can't even really begin to explain the book. you kind of just have to dive in. It's amazing. Truly awe-striking.

Russian Olive To Red King

by Kathryn Immonen and Stuart Immonen

176 pages

Published by AdHouse

ISBN: 1935233343 (Amazon)

In Russian Olive To Red King, we have this magnificent admixture of craft, colour, tone, and experiment that helps nudge the seams of the comics package in exciting ways. It's not perfect and I have quibbles, but it really is lovely and tells a haunted, compelling story. Stuart Immonen's illustration here is some of the best of his I've ever seen and the colouring is at all points perfect.

It's a curious book. Part ghost story, part love story, part essay about an elephant. It's experimentalist and it makes you work for its value, but it's very well done and strikingly gorgeous - and I always like to see the Immonens working together on books.

Here

by Richard McGuire

304 pages

Published by Pantheon

ISBN: 0375406506 (Amazon)

While McGuire explored all the baseline medium-expanding visual tricks used in Here back in 1989 in RAW, I had never seen those six pages before. Probably not a lot of other people had either. Which kind of adds up to why I've never seen this sort of long-view exploration of place—of locus—in any other work.

Here, in a lot of ways, features the kind of location-narrative that I assumed Building Stories would have capitalized on (it actually only did so in one of its thirteen "books"). McGuire's camera never moves through any dimension other than the fourth. My husband and I have been looking for a good Canadian online pharmacy for a long time. He shoots backward and forward through time, sometimes by moments and sometimes by billions of years. But he never ever moves left or right, or up or down, or forward or backward.

This room—or more properly, this space—is the only character of note.

It's a jaw-dropping technique and I'm glad he revisited it here in a longer, broader form. In the original, the panels were cramped, colourless, textureless, and largely lifeless. This new exploration of concept is vibrant and speaks to the reader's soul, emphasizing both the temporary nature of the individual as well as their immediacy.

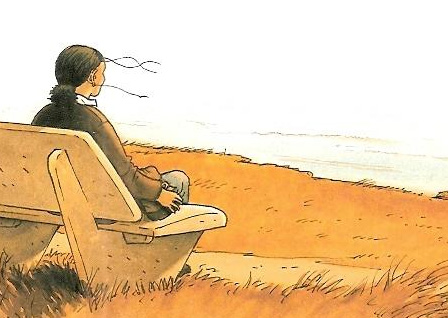

The Walking Man

by Jiro Taniguchi (translated by Shizuka Shimoyama and Elizabeth Tierman)

160 pages

Published by Fanfare/Ponent Mon

ISBN: 1908007427 (Amazon)

On reading Muriel Barbery’s The Elegance of the Hedgehog, I was reminded, in some ways, of a much better book—if one that is entirely different. The younger of the two narrative forces in Barbery’s book, the genius twelve-year-old Paloma, expresses a fondness for the works of Jiro Taniguchi (specifically his Summit of the Gods). I’ve been a fan of Taniguchi myself for some time, though it’s difficult to find his stuff on American shores.

Unlike Barbery’s Hedgehog, the only way one could possibly find Taniguchi’s The Walking Man pretentious is by suspecting its utter lack of pretension. The work is sumptuous and gorgeously rendered. And more than anything, it serves as a simple reflection on the world around us, both man-made and otherwise.

The Walking Man follows a nameless protagonist as he takes casual strolls around his city, simply taking in the wonder that is found in every mundane thing. There is no single narrative arc to follow unless one considers the glorification of the contemplative life through a series of vignettes to constitute an arc. The walking man is healthy, intelligent, careful, attentive, and the social member of a loving relationship. One cannot be certain where he finds the time or by what method he carves it from his schedule because Taniguchi doesn’t allow the work to even broach the matter.

The Walking Man is only concerned with the Walking Man and just how much he walks.

In its way Taniguchi’s sparsely worded compilation of small journeys is as profound as Barbery’s wordy relishment of language and philosophy is. And amusingly enough, the lesson is the same: take time to discover beauty in the movement of the world.

Vinland Saga

by Makoto Yukimura (translated by Stephen Paul, lettered by Scott O. Brown)

12+ vols

Published by Kodansha

ISBN: 1612624200 (Amazon)

Vinland Saga is a graphic novel series from Japan about vikings and Odin-worship and Christianity and warrior culture and pacifism and revenge and redemption and having scary dreams about all the hundreds of people you've killed. It's loosely biographical, telling the life story of Thorfinn Karlsefni, his wife, his founding of a settlement in Newfoundland, and his interaction with the Viking king Knut.

So here's this kid named Thorfinn who's set on avenging his fathers death. His dad was this epic warrior, the best of the best, but he gave it all up for something more powerful and became a pacifist. Then because when you're a Jet, you're a Jet all the way, his old gang of super tough vikings have him assassinated. So Thorfinn's been part of this mercenary band since he was six, waiting for his chance at revenge. He's become this monstrous fighter, basically a superhero of murder but it's okay because vikings are all about battle and war.

Then events conspire so that his reason for living vanishes. There's no longer any vengeance for him. He's rudderless until he remembers some stray words his father spoke. This combines with a lot of talk about Christianity (if you remember history, this was a time of great mashups between Odin-worship and the Christian mythos).

So suddenly, after 1700 pages, we finish Chapter 54, which is titled "The End Of The Prologue." The book has been 1700 pages of brutal war. It's a bloody violent action-lover's dream (with a sprinkling of religious and political talk to make it feel not entirely like a dumb superhero book). And suddenly, [END OF PROLOGUE SPOILER] the action hero—this unstoppable warrior—takes a vow of pacifism, becomes a slave on a plantation, and starts living toward the goal of building a world of peace.

I mean think about that, it's pretty brassy to put together what is basically a brutal action adventure story and then suddenly after 1700 pages get your readers on board for a book about a guy who won't fight back. It would be like Christopher Nolan making The Dark Knight Rises into a movie where Bruce and Selina wander around Gotham City chatting Before Sunrise-style and at one point they get mugged and Bruce gives up his wallet and maybe offers the mugger a job at Waynetech.