This is picks 201-300 of Good Ok Bad's Top 500 Graphic Novels Of All Time. Follow the links below to get elsewhere in the list.

201–210211–220221–230231–240241–250

251–260261–270271–280281–290291–300

My Best 500 Comics Of All Time (201-300)

Mister Blank

Christopher Hicks

152 pages

SLG

ISBN: B01N4HY7FJ (Amazon)

It's always a shame when a book falls between the cracks. When either the world isn't ready for it yet or its creator just hasn't had that magic string of luck that means their book will get the accolades and adulation. Every year I read ten or twenty books that ought to be famous, that ought to be among the books that everyone is talking about that year, but somehow just don't catch fire like they should.

Mister Blank is an old one of those. Published in its complete form in July of 2000, Hicks' adventure burst out just before the dawn of the new golden age of comics. There were greats that predated it by a year or two or were contemporaries, but the era of people looking to the graphic novel as a trustworthy source of great storytelling and literary wonder had yet to fully take root. Would Mister Blank find a great and robust audience were it released today? I've given up trying to predict what will catch hold of the popular imagination. When Balak, Sanlaville, and Vives' Lastman doesn't find itself prominent on every sci-fi/fantasy adventure reader's shelf, prognosticating a book's success seems a fool's errand.

At any rate, Mister Blank is 17 years old and out of print *but* unpopular enough that you can get used copies off Amazon in the neighbourhood of $15. Which is a steal. Because at the end of the day, Mister Blank is among my all-time favourite adventure comics. It's funny and exciting with dynamic art and a great sense of visual timing.

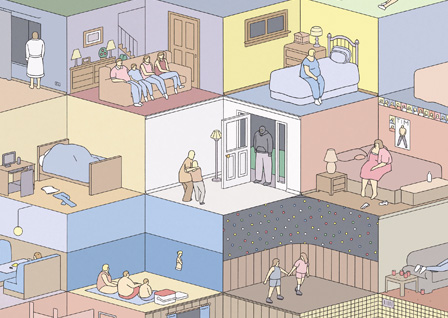

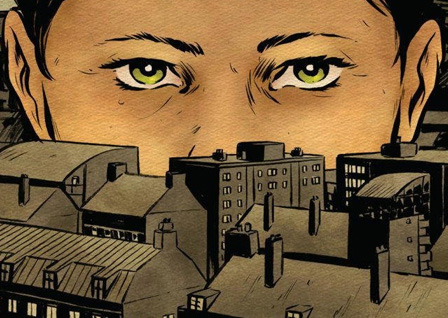

Story brief goes like this: Sam Smith is a nobody in a big corp. He loves his dog and has a crush on Julie but is too chicken to mention it, which is sad because she keeps waiting for him to make a move. Anyway, as we would expect, a couple terrorists try to blow up the corp building and Sam stops them. Only they were robots, not terrorists, and they weren't necessarily trying to blow up the building but they did accidentally drop some biomass that's cloned Sam and given a street mime superpowers. Also, there's a guy who flies because he might be related to Satan. Also a bunch of dudes who are immortal. Also is that Litlith, the first woman (the one before that upstart strumpet Eve), and oh yeah her daughter and does she know the word of creation that she stole from God? Maybe. Or probably. Because that's how stories about corporate peons always turn out.

Anyway. If you like fun, you should read it. Get it from the library or get it as a not-too-pricey used book somewhere.

Sparks

Lawrence Marvit

424 pages

SLG

ISBN: 0943151627 (Amazon)

Josephine, the book's protagonist/damsel in distress, is utterly human. She's sad and tragic and naive and wobegotten. And entirely likable. Every time she is snubbed, mocked, ignored, or abused, I am hurt. Josephine is one of those characters that you get to watch grow. She begins as timid geek-girl (she's an auto-hound) and slowly musters courage at the prompting of some dubious friendships. But courage needs to be earned and her initial attempts at freedom from her fears are only as successful as any halfhearted endeavor can be. And so, she needs to grow through the experience of pain and love and rejection and abandonment and love and death and terror and love. And love. And it's wonderful and I rejoice in her character and her victories.

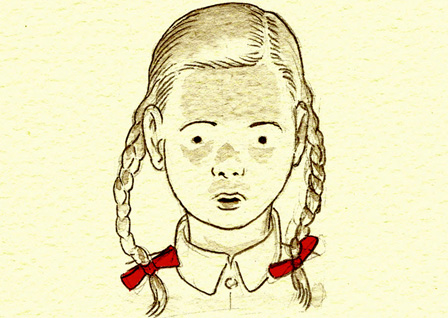

Miss Don't Touch Me

Hubert, Kerascoet

2 vols

NBM

ISBN: 1561638994 (Amazon)

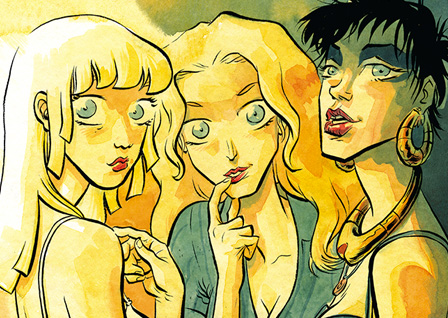

Set around the turn of the 20th century, Miss Don’t Touch Me concerns two sisters (one a flirt and the other a prude), suburban dance parties, a serial killer, a brothel, and the dish best served cold. Reserved Blanche becomes accidental witness to the Butcher of the Dances, and her sister Agatha falls victim to the killer who hopes to cover his tracks. Blanche is destroyed emotionally but this devastation propels her into the journey of detection and subterfuge for which she’ll have to be steeled if she wants her revenge. Circumstances lead her into the employ of a brothel where her prudishness and refusal to be touched by a man lead her to become the shop’s special dominatrix. Dressed as an English maid, she whips, beats, and savages every single one of her clients, earning herself the title Miss Don’t-Touch-Me. Yet as she gets nearer to identifying the killer, she comes closer to falling into the killer’s path. It’s a treacherous road and the book functions well as French neo-noir.

Gotham Central

Greg Rucka, Ed Brubaker, Michael Lark

5 vols

DC Comics

ISBN: 1401220371 (Amazon)

We pretty much all know by know that I am not at all a fan of Marvel/DC superheroes, right? Like, I think the structures of the genre and its market expression actively thwarts the emergence of decent storytelling and characters that matter at all. It's a bad scene. So much squandered potential, so sad.

BUT! There *are* occasional gems. Alias, Bendis's Daredevil, Langridge's Thor, Ultimate Spider-Man (to some extent), Simonson's Thor (to some extent). And Gotham Central.

Every character in Gotham Central, a book about precinct detectives in Batman’s Gotham, is at odds with the DC Universe. These are detectives trying to solve cases in a world where Batman can seemingly solve any crime so long as he’s given enough time (there is only one of him after all). So really, less than being the only way that families and loved ones can gain closure after a terrible crime, these detectives really just find themselves stuck in a sort of game of Cops and Batman. The goal of the game is of course to close cases before Batman does. The detectives pretty much rely on the fact that Batman will get the collar if they’re too lazy or too dense or too unlucky or too overmatched, so the book tends to play a lot on their frustrations with a game that is rarely tipped in their favour.

Of course, most of this is subtext and Rucka and Brubaker rarely get mired in that aspect of Gotham Central's world, but it’s always there, always present. And it goes a long way to explain these detectives’ short tempers and overtly competitive feeling toward Batman. They all seem well aware of the idea that were there more Batmen, they would all be obsolete, unnecessary relics of that brief period of law-enforcement history when there were no indefatigable costumed vigilantes.

And because this foundation of the story generally remains in the shadows—much like the Bat himself, only appearing at opportune moments to assert his presence and remind us of just whose city we’re visiting—Brubaker and Rucka are able to tell some just plain good crime stories without having to worry so much about heroes and villains. Of course Batman has to make his appearances and of course his rogue’s gallery is bound to take their part as well, but Gotham Central succeeds in keeping a lot of that noise off-screen, where we’re aware of its presence but can pretend alongside the detectives that its the normal people, the citizens, victims, and detectives who are the ones who matter.

It’s all part of the game and Rucka and Brubaker are happy to help us play along.

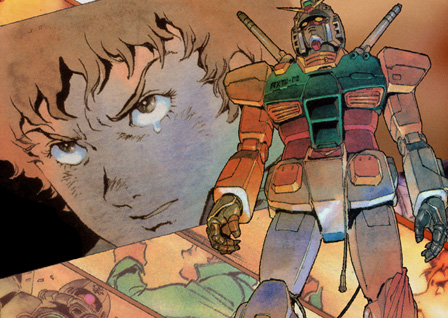

Thor by Walt Simonson

Walt Simonson

5 vols

Marvel

ISBN: 130290888X (Amazon)

Simonson’s writing is superb. The ideas that govern Marvel’s Thor are from another era and not in-line with the sensibilities of contemporary audiences. Simonson defeats this problem perhaps effortlessly (at least it seems so) by giving all his characters overly dramatic monologues, which they happily trade back and forth as if in dialogue. Their language is ludicrously flowery and their verbal ticks would be clownish if it weren’t for their identities as gods. Somehow all this over-writing works—the characters and their lives become fascinating and engaging, something worth the readers’ time to pursue.

One of the glories of Simonson’s run on the book is that the whole thing (nearly) reads as a single story. While that sort of thing happens much more often post-AD 2000, in the mid-’80s, such a long-running arc was pretty rare. The first chapter of this omnibus begins with a great and shadowy figure slamming down a tremendous flaming ingot (made from an exploded galaxy) onto an anvil. The sound that ingot produces as it makes first contact with the anvil is an ominous onomatopoeia that echoes across the universe: “DOOM!” It’s a famous image from the era and recurs throughout the work while this particular piece of Simonson’s saga works itself out. From there, story after story spins out, each the natural result of what came before. With few exceptions (and they seem to be publisher-mandated annoyances), nothing within the work stands alone.

Simonson also shows a wonderful knack for story beats. His narratives skip all over the place, with a page devoted to one character followed by two devoted to another followed by a half-page devoted to a third before returning to the first and then introducing a fourth. I’d say it was staggering to consider how he keeps so many narrative balls in the air while maintaining such a crisp story pace, but nowadays it seems like any number of worthwhile manga that hit American shores do the same. As well, Simonson seems happy to deliver several kick-ass moments per chapter—from charges against unbeatable foes to noble self-sacrifices to remembrances of those sacrifices to laugh-inducing come-uppances. Simonson the writer delivers.

But as much fun as Walt Simonson the writer is, it’s probably Walt Simonson the artist who most viscerally turns Thor into a hero whose songs we want to learn. Simonson himself is on art chores for the first two-thirds of the book and when he bows out to keep strictly to the writing aspect, the book is poorer for the loss. It’s not so much that Sal Buscema is a poor artist—it’s more just that he’s not Walt Simonson. (Simonson returns for the the big climax in the third-to-last chapter, and if that battle had been drawn by Buscema instead of Simonson, we’d be missing one of the greatest single chapters in comics history.) Simonson’s art is rough and tumble, full of a kind of visual braggadocio. He makes these gods look as if they might actually be warriors. His design sense reveals a kind of dynamism that was largely missing from the era in which he worked (and isn’t really apparent today either).

That I can unreservedly recommend this massive collection does not mean that there aren’t issues with the work. After Buscema takes over on art, it seems like some of Simonson’s writing spark wanes as well and I’ve always felt it difficult to be as invested in some of the latter stories. Another issue is due to a couple interruptive crossovers. In the aforementioned Power Pack crossover, the kids from Power Pack suddenly appear and are suddenly gone, and today’s readers will probably have no idea who they are or what place they have in Thor’s world. Even worse though, the primary McGuffin from Marvel’s Secret Wars miniseries shows up having resurrected one of Thor’s foes who had been killed earlier in the volume (the resurrection happens in another series and is not reproduced here). Later in the series, Thor gets shoehorned into participating in the X-Men event “The Mutant Massacre.” And in another instance, occupying three bare panels, a costumed supervillain is unceremoniously murdered by a homeless person; it’s part of the Scourge storyline running through Captain America’s book at the time, but doesn’t make any sense to readers without that kind of knowledge. These episodes are a shock to the system and a great argument against crossovers in the midst of ongoing stories. While the pagecount is already high, it would’ve been nice to have had some sort of explanation of these things—if this book is meant to be a kind of stand-alone omnibus.

Death Note

Tsugumi Ohba, Takeshi Obata

13 vols

VIZ

ISBN: 142152581X (Amazon)

The fact that you’re reading about these very intelligent characters who think things through to incredible lengths only adds to the excitement. There were moments of revelation and counter-revelation that simply blew my mind. There are moments when you think the jig is up for one or more of the characters and then a flashback will reveal the would-be victim’s plan from the start and you get to see tables turn and over turn as these characters fight for their lives. In a way, it’s kind of a cheat, withholding essential information from the audience in order to up the tension ante, but the solutions are generally smart enough that most readers probably won’t mind being led on in this manner.

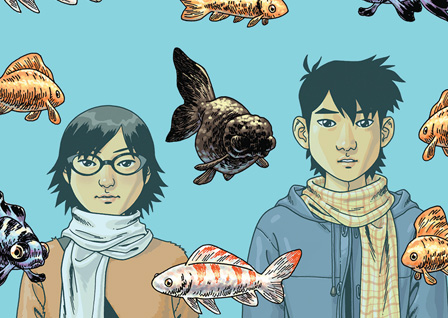

Spirit Circle

Satoshi Mizukami

6 vols

Seven Seas

ISBN: 1626926018 (Amazon)

With Spirit Circle, Lucifer And The Biscuit Hammer, and the recent anime Planet With, Mizukami proves himself reliably imaginative creator. Spirit Circle, despite being conceptually fascinating, may actually be the most mundane of his stories I've so far encountered. Two kids and their friends are somehow tied across lifetimes and continually reincarnate in intimate proximity to each other. The story begins as the new girl at the school proclaims that she is going to kill the protagonist. Because he is baffled, she provides him the means to investigate his past lives to discover why he must be murdered. The whole thing is a lot of fun and gets conceptually pretty wild by the end.

The Wrenchies

Farel Dalrymple

304 pages

First Second

ISBN: 159643421X (Amazon)

Wrenchies features that gorgeously janky Dalrymple visio-narratory aesthetic. It's a weird little book that isn't really all that weird after all. Lots of relatable motivation and heart.

Epileptic

David B.

368 pages

Pantheon

ISBN: 0375714685 (Amazon)

I’ve known several people over the years who’ve suffered on and off (usually more off than on) from seizures of one sort or another. Fortune favouring me over them, I’ve never witnessed an episode and have only heard tales secondhand. I have however witnessed several faintings. The two are not really at all comparable save for the definitive theft of control from their victims. So while I’ve never witnessed an epileptic event, I am suitably horrified by the possibility.

Every person values control, and self-control above all. Children throw tantrums because they are denied control over a world that shuffles on heedless of their whims. Stereotypical mothers-in-law (and, I would hazard, all the other kind as well), bridle over the fact that another woman has usurped the office of responsibility for their son’s welfare. The lasting terror of rape is often described not as some revulsion for physical contact as such, but disgust or anger or horror at the abject violation of one’s right to control access to one’s physical self. Determinism and destiny are ideas that choke us on their callous disregard for what we want. Control is everything for us.

So it makes sense that David B’s recitation of life with a severely epileptic brother would stand as an unveiled monument to control. Control is the very thing that neither David nor Jean-Cristophe, the epileptic brother, possess. And in each their own way, they are desperate for it. After all, who wouldn’t be?

Jean-Christophe, the elder brother by two years, begins his rather-too-short battle with epilepsy when he is seven years old. He fights for a time, but quickly succumbs. Life without control is too hard on him. He gives in to the monster who’s been pursuing him and becomes a pathetic creature and burden to his family. He is never not human, but in the end it barely seems to matter. He is rage and sloth and mania. He cannot see control existing on any horizon and so he relinquishes entirely his hope in self-control to the end that he might become a burden on those who spawned him, exercising at the least a measure of control over the lives and schedules of his caretakers.

David, our Virgil on this descent into the heights of madness, is little better off than his brother. He is five when catastrophe hits his family with tidal force. The next fifteen years of his life are governed by his brother’s monster and his parents’ wild, grasping attempts to destroy it, or at least placate the beast. David is determined to fight and come out victorious. He will not give up control, even as it is wrested from his grip. He retreats to fantasy worlds, where he might gather strength enough to lay a siege in the real world. He makes his home among dreams and daytime imaginations, steeling himself against real monsters by governing those of his own creation. Fantasies being no match for the terrors of reality, he finally retreats to the last and weakest bastion of the truly defeated: a deep and abiding cynicism.

Epileptic, in many ways, is less the story of Jean-Christophe and more a cathartic journey by which David B can finally rid himself of his dreams, his fantasies, and his cynicism. And more than anything, it may be his way of finally exerting control over his life by coming to terms with the fact that he holds no control over such things and never will. It’s a powerful and compelling journey if one has the patience for it.

Epileptic is terrifying and needful, boring and important.

From Hell

Alan Moore, Eddie Campbell

576 pages

Top Shelf

ISBN: 0958578346 (Amazon)

From Hell alternates between being interesting and being soul-crushingly tedious—more often the latter. But (!) it remains for me Alan Moore's best and most ingenious work. I don't care for it but there's still something admirable about it as a project, and there are some chapters and pericopes that are just plain incredible. Like one told from the perspective of Gull's belly that charts his whole life story.

201–210211–220221–230231–240241–250

251–260261–270271–280281–290291–300

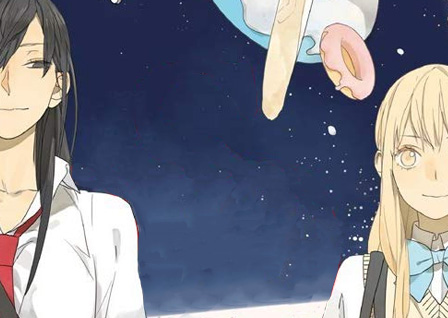

My Love Story

Kazune Kawahara

13 vols

VIZ

ISBN: 1421571447 (Amazon)

It took me a couple years to give My Love Story a shot. I wasn't taken with the art. It kept me from bothering with the series. But man, you guys, I loved this story. And the art gradually became rather charming to me. Earlier in this list, I highly recommended Horimiya, a wonderful progressive love story. I love Horimiya so much but if there's one part where it falls down a bit, it's with side character creep. Gradually as the series goes and new side characters join the book, we get less and less focus on the main couple, who are the reason why we're reading the story in the first place. My Love Story doesn't have that problem. This is about Takeo and Yamato from beginning to end—and any stories dealing with the side characters are there to serve the telling of the main story. It's refreshing to see such a single-minded pursuit of a story about a boy and his girlfriend. My Love Story is progressive romance (i.e. one that moves beyond the meet-cute and the will they/won't they question, exploring their life as an established couple and beyond). Takeo is a 6'6" muscular and forthright 15yo boy (who people mistake for an imposing and therefore creepy adult) and has had zero luck with the ladies despite being incredibly popular with the guys. Early in volume 1, he rescues Yamato from a groper on the train and after an initial confusion where Takeo thinks she's interested in his friend, they start dating. All this happens in the first half of vol 1. The rest of the 13 vols is exploration of their relationship given their personalities and insecurities. And it's kind of delightful. One other aspect I appreciated was the deep love between Takeo and his best friend Sunakawa. They care so much for each other and are deeply invested in each other's happiness. It was pretty beautiful to see. I got the whole thing from the library and binged it over the course of three days. I'd probably recommend taking more time with it than I gave.

Shirley Jackson's "The Lottery"

Miles Hyman

160 pages

Hill and Wang

ISBN: 0809066505 (Amazon)

When you see, Oh look, some guy adapted another piece of classic American literature into the graphic novel form, and you think, Oh joy, what a waste of time—when that happens, 10 out of 10 times you're on the right track. Skepticism toward comics adaptations of great literature is well-founded and merited. The products produced are nearly always trash.

But not this time.

Shirley Jackson's story is dark, sinister, and impressive. But for me, as good as it is, it was always waiting for this: the moment when Jackson's own grandson would take his grandmother's signature work and draw the hell out of it, delivering this amazing thing that (for my money) actually improves on the original work. I don't understand his brand of witchcraft but I was awed. This is a gorgeous work, the illustrations lush and evocative. (Caveat: the lettering is a weakness.) I was delivered into Jackson's world like never before.

Princess Jellyfish

Akiko Higashimura

9 vols

Kodansha

ISBN: 1632362287 (Amazon)

Oh man Princess Jellyfish was a lot of fun. Higashimura takes a cast of characters I don't really like and lets them (most of them at any rate) charm me into enjoying their antics. Both my wife and I audibly laughed or chuckled our way through the series. And while at nine vols it feels a bit padded out (five probably would have been better), we both pretty thoroughly enjoyed our time in her world.

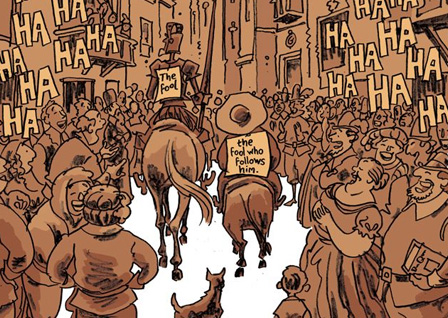

Peter Pan

Régis Loisel (translated by Nicolas Rossert)

336 pages

Soaring Penguin

ISBN: 1908030070 (Amazon)

In preparation for reviewing Régis Loisel’s Peter Pan, I thought it necessary to show due diligence by reading J.M. Barrie’s novel, Peter and Wendy. I’m glad I did. Not only is Barrie a fantastic writer with a grand taste for words (and the worlds their interplay can invoke), but I found the opportunity to have my conception of Pan entirely overturned. I, like too many others, have had my entire familiarity with the character dictated by the sanitized Disney product.

Most of us are familiar with Disney’s penchant for trimming and reframing classic stories into confections made palatable for audiences in the lowest common denoninator (in this particular case, terrified moralists). Under Disney’s pen, Hans Christian Anderson’s littlest mermaid does not lose her tongue, does not walk with excruciating pain, is not tempted to murder, and does not perish in the end. Disney’s Pinocchio does not kill the talking cricket at the beginning of the story. Victor Hugo’s finale doesn’t end in a litany of death with Disney at the helm. The stories of Cinderella, Snow White, Sleeping Beauty, Pocahontas, Aladdin—all paved over, gently landscaped, tidied, and made wholesomely presentable by the Disney company. Some of these stories survive their crisp evolution and become their own wonderful selves in a kind of cinematic afterlife. Others, like Peter Pan, fair less well. Not only does the story lose Barrie’s ingenious narration, the chief and principal joy of the book, but Pan’s character and world are eviscerated, losing all of the frightening terrifying heart that makes Barrie’s story so wonder-strikingly perfect. I’m actually somewhat upset at Disney for turning such a work of beauty into the anemic sort of innocuous adventure we find in their Peter Pan. Their version kept me from reading the original for more than three decades.

It’s fortunate that I had begun Peter and Wendy before embarking on Loisel’s journey with the character. Had I not, I would have been broadsided entirely by a crass, violent, sexist, and sexual vision of Peter Pan that stands strikingly at odds with Disney’s depiction. I would have chalked the book up as merely yet one more of the revisionist trend of reconceptualizing faerytales into dark, modernized treats for the Cynical Generation (shoutout to muh peeps). While reframing classic stories to be “more realistic” was cool for a while, it’s been done and redone and overdone so many times that it’s passed well into the realm of cliché by now. Adding to Disney’s sins, they almost had me believing that Loisel’s take on Peter was typically revisionist. But it’s not—not at all. Rather, it’s probably more properly viewed as devotional. It’d be counted fanfiction save for its production value and narrative strength.

Loisel’s origin story for Pan susses out so many of the terrible little deviancies that Barrie’s Peter and Wendy coyly includes. Barrie’s story took place in a world of violence and sex and anger and depravity, but Barrie consciously told his tale in a manner fitting for young listeners. It’s a deeply whimsical work, subversive in how baldly it glosses the depravities at stake in Peter’s world. Via Peter and Wendy, we find numerous dark surprises. Peter kills off Lost Boys as they grow too old for his taste. The Redskins are naked save for a decoration of scalps, some belonging to the Pirates, some belonging to Lost Boys, and their chief is so thoroughly overburdened with such decorations that he has difficulty sneaking. Tinker Bell conspires to have Wendy assassinated by a Lost Boy (with an arrow to the chest) and is successful until it is revealed that a bare chance caused the arrow to glance from her heart. Tinker Bell is portrayed as a bit of the sexpot, endowed with a generous bosom and wearing a scant leaf as a dress in order to best show off her figure. The faeries are a randy bunch and given to orgies. Peter has a fondness for meting out mortal violence. Barrie recounts that Peter will come home with stories of great adventures—only in the light of day no body can be found; at other times he will come home with no story at all—yet come daylight, we find a corpse in plain sight. Hook routinely murders his crew members for various slights and perceived slights. In Wendy, John, and Michael’s flight from London to Neverland, the journey is so long that Michael falls asleep and plunges from the air toward death in the waves below; Peter dives and rescues him spectacularly at the last moment, but Wendy suspects that Peter is indifferent to the saving of Michael’s life and wouldn’t have bothered save for the fact that he could look heroic doing it. Neverland drains its inhabitants of their memories and so Wendy and the boys begin to forget their former lives, but Peter, who’s been there longest, has no memory of his former life nor of many other things. Wendy continually must remind Peter of who she is. When Tinker Bell finally dies, Peter quickly forgets that she ever existed.

Had I not discovered that this was the character and realm that Loisel needed to build toward, I would not have been able to understand his work for what it is. Loisel’s Peter is not yet the Pan that Barrie would reveal to the world, but he’s on his way—and unlike Barrie, Loisel does not have any reason to hold back the grim clouds inherent in Peter’s tale. Barrie’s story is a gathering of light in a world of profane darkness; Loisel’s is the story that justifies Barrie’s requirement of light. To that end, Loisel crafts a visual narrative that capitalizes on an adult readership—and the grown-ups (parents, uncles, aunts, grandparents, and teachers) who take the time to investigate Loisel’s Peter Pan will find themselves at a place to better understand Barrie’s original, as well as the profound need for Barrie’s steadied voice from within that maelstrom.

While Barrie’s Peter is grounded in Edwardian England, this prequel is founded a quarter-century earlier in a Victorian London more reminiscent of the filthy streets of Dickens than the drawing-room comedies of Oscar Wilde. Loisel’s London is dirty and sinister, on the cusp of reeling under the terrible shadow of the Ripper. The city is rife with whores and pedophiles and thieves and drunks. It’s a world of foul deeds and befouled hearts. And it’s here that we first find Peter, not quite fortunate enough to be an orphan. Through six meaty chapters Loisel helps Peter divest himself of his memory, his person, his humanity—all to the end that he might become Barrie’s eternal child-monster.

Yukiko's Spinach

Frédéric Boilet

144 pages

Fanfare/Ponent Mon

ISBN: 8493309346 (Amazon)

Autobiography is by its nature one of the more conceited art forms. Concocting a story of one’s own adventures to the end that they will be enjoyed by a readership of more than one’s own friends and family takes a fair amount of self-confidence. Or hubris. Or arrogance. To imagine that one’s own story is as valuable a use of a reader’s time as a fictional character’s takes guts. Or moxie. Or chutzpah. And then for an author to specially select for his autobiographical pericope a couple months’ dalliance with a young woman and detail his own skill as an adventurous lover—what does that take?

Frédéric Boilet’s apparently autobiographical* Yukiko’s Spinach is part journal, part intimate recountment of a two-month-long interlude with a girl he meets at a gallery opening in Japan. So far as romances go, we learn from the start that this one is probably doomed to a brief lifespan since Yukiko, the object of Boilet’s interest, is herself interested in someone else and will pursue that entanglement as soon as opportunity allows. It’s in the meanwhile that she’s willing to engage Boilet (or his autobiographical avatar) in some fitful and adventurous physical pairings, necessarily accelerating the evolution of their relationship at unnatural speeds towards its foreseeable culmination.

As a book primarily interested in Yukiko’s temporary place as Boilet’s carnal muse, the book amusingly (from a very meta perspective) goes to deliberate lengths to demonstrate Boilet’s part as a persistent, attentive lover. Whether absolutely non-fictional in this aspect or not, Boilet posits a version of himself that is a kind of indefatigable superman of the intimate. In the midst of their congress, he lingers over every part of Yukiko’s form, making each portion of her body a new standard of beauty, even to the point of remolding imperfection (such as chicken pox scars) into aesthetic wonders. He turns every private moment into an opportunity to once more ravish his lover, disrobing her even as she dresses from their most recent congress.

Yukiko’s Spinach exists as a revelry in a moment, a snapshot of the perfect vacation marred only by the inevitable collapse and loss at its conclusion. As autobiography, one wonders what Boilet was trying to communicate to himself—for memoir as often speaks some truth to the author as it does to the reader. If he seems somewhat set adrift (exemplified by the transient nature of his dalliances), perhaps that is a reflection of his status as a resident foreigner. He’s clearly looking for stability but simultaneously doesn’t seem to rely on its attainability. Boilet’s character seems a man trapped in flux. It’s an interesting place for a protagonist to be and most of us could probably relate on some level from at least one moment in our lives.

One of the standout praises Yukiko’s Spinach will receive almost across the board is in regard to its artistic vision. The reader sees the story unfold almost entirely in the first person. The camera through which we encounter Boilet’s experience with Yukiko is, for the most part, lodged in Boilet’s own eyes. It’s a curious technique and we are treated to a man with a perspective that roams over the entirety of his surroundings, rarely meeting Yukiko’s gaze eye-to-eye. Through this scattering of vision, Boilet unveils a character that might otherwise remain unknown. His avatar is made real by his evident distractions.

With its rugged and frank sex scenes, Boilet’s book will not be appropriate for some readers and may put off others. Personally, I did not find the book (for all its explicitness) erotic. Perhaps it was the documentary nature of the thing or its surreal first-person presence, but I felt that Yukiko’s Spinach was more an anatomy of a relationship than a lush and purposed turn-on for those in search of a sensual thrill.

*note: It does occur to me that this may not actually be autobiography, that it may instead be some kind of hyperfictionalization of Boilet’s experiences—a kind of codified wishful thinking on the author’s part. While that would certainly complicate the reading, I think it would make for a more delectable interpretive puzzle.

West Coast Blues

Jacques Tardi (adapted from Jean-Patrick Manchette)

80 pages

Fantagraphics

ISBN: 1606992953 (Amazon)

If you like crime novels, you'll want to get ahold of this adaptation of 1976's Le Petit Bleu De La Côte Ouest. Tardi's illustrations under Manchette's delightfully succinct, incisive, and spare narration is a wonder. It's short at 80 pages but those pages are full-to-brim with content. West Coast Blues sits in my top 5 favourite crime graphic novels.

The Tale Of One Bad Rat

Bryan Talbot

136 pages

Titan

ISBN: 1852866896 (Amazon)

The Tale of One Bad Rat is one of those classics of the medium, one of those books that was an indelible footnote in the quest to prove that comics could be about more than just superheroes and melodrama. Whether Bryan Talbot’s intent or not, One Bad Rat became one of the arguments for comics being a medium of communication worth the same level of serious consideration as literature. Or if not literature, then at least the same sober reflection that cinema could garner. In a way, that’s kind of an unfair burden to saddle upon this slim graphic novella. One Bad Rat does two things for the medium. It presents a serious issue in a dramatically plausible way and it incorporates literary allusion in a largely worthwhile manner.

Young and homeless teen protagonist Helen plays refugee from two abusive parents, trying to muddle her way through a world that cannot make sense to a mind scarred so early and deeply by counterfeit love. Over the book’s first half, Talbot offers an empathetic look at how life outside of a home might play out. It’s a heavy read, though not so heartbreaking as it could be, largely because Talbot keeps the real problem off-screen and unspoken for most of the journey. Certainly there are allusions to the sinister throughout, but the true horror of her situation is never laid out gratuitously.

Beyond this, Talbot not only makes Helen an ardent fan of Beatrix Potter (her life and works), but skillfully uses that character-interest to build his story. Helen sees things in Potter-esque terms. For much of the second half of the Tale, she is accompanied by a human-sized rat, functioning as silent confidant. That Helen would grasp onto Potter’s history and millieu so strongly makes good sense in the world of Talbot’s telling and it gives one the sense that One Bad Rat is something more than just one more trite examination of abuse. Beatrix Potter becomes a talisman for Helen, one by which she hopes to find the strength to grow beyond her terrible past.

Hilda

Luke Pearson

5 vols

Nobrow

ISBN: 1909263141 (Amazon)

What began in Hildafolk (later retitled Hilda And The Troll) as a kind of queer story about a young girl and her love of faerylore that was almost certainly meant for grown up readers has become one of the greatest series of graphic novels aimed probably at young readers and grown-ups who like faery stories.

In the beginning, Hilda and he mother live in the hills near to nature and near to supernature. There are trolls and elves and giants and men made of wood. Hilda adores them and the adventure they represent. The first volume explores her conflict with a stone troll. The next involves tiny invisible people and giants as tall as mountians. In the third, she and her mother have moved to the city and Hilda finds that even in the stifle of civilization, magical creatures thrive and survive. And it continues.

The Hilda books are about finding wonder in the wonderful, but also focus on Hilda's relationship with her mother who often doesn't know quite what to make of her daughter's free and wandering spirit but simultaneously doesn't want to squelch the life in the one she loves. It's a wonderful series and I'm glad Pearson has continued them.

Venice

Jiro Taniguchi

128 pages

Fanfare/Ponent Mon

ISBN: 1912097044 (Amazon)

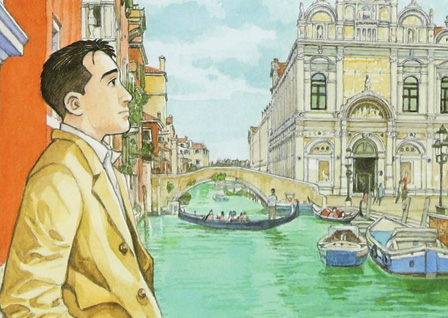

So Louis Vuitton hires these artists to do travel books for them, basically a carnet de voyage. They'll get ahold of an artist and send him or her to a location they've never been before and the get back a book of paintings of that place, which they'll then publish in a pricey little art book. Lovely stuff, nice for coffee tables. They tapped Taniguchi for the series a number of years ago and as Taniguchi does, he turned it into a narrative about, surprise, a man wandering around Venice taking in the sights.

Here's a 4-minute video of Taniguchi talking about the project:

The frame is that the man found among his deceased mother's things a lacquer box filled with photos and some small watercolours from Venice a long time ago. In the photos are a young woman (his grandmother?) and a child (his mother?), and occasionally, a young man (his grandfather?). As he travels around Venice he tries to match up locations with the photos and the watercolours—and along the way hopes to get some better sense of his family and their history. The narrative is slight but affecting. The real draw, however, is Taniguchi's gorgeous paintings of the city. Some are good, some are beautiful, and some are awestriking.

Ranma 1/2

Rumiko Takahashi

26 vols

VIZ

ISBN: 1421565943 (Amazon)

Ranma 1/2 is, sort of, just an amusing trifle. You can hang around for a little or you can linger and take in the whole thing. It probably doesn't matter, but as long as you're reading you're probably also having fun. Takahashi keeps things lively even when the will they/won't they question of the book's principle ship has long lost its luster.

201–210211–220221–230231–240241–250

251–260261–270271–280281–290291–300

My Favorite Thing Is Monsters

Emil Ferris

2 vols

Fantagraphics

ISBN: 1606999591 (Amazon)

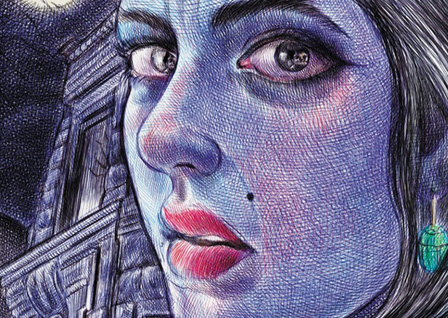

My Favorite Thing Is Monsters does some things very very well. The use of ballpoint pens (or possibly pen-emulating digital brushes) is awesome. Ferris' use of colour here is almost incredible. As well, the bouncing around of the narrative and the discrete release of revelations works very well.

On the other side, page and panel flow can be awkward and often enough I gave up trying to guess in which order I was meant to approach text blocks and balloons.

As well, I struggle to buy that the narrator/artist is ten years old; there's things that feel like discrepancies (I guess) where she's handing out Valentine cards in class (a pretty ten-year-old thing to do) but then a week later being threatened with actual penile penetration by classmates. Maybe that does happens in fifth grade (!?) but I know I wouldn't have had the physical development required to have sex with anyone back then, and I was old for my grade.

But this discrepancy may be intentional. Karen from the first proves that she has an overactive imagination that she is full-well ready to believe as fact, so maybe that will play a role. It could be that Karen really is in high school or something and is only portraying herself younger for reasons to be revealed. (She depicts Franklin as a classmate in the Valentine's scene, but he looks Much older than 10yo in later scenes.) Also, Sandy probably doesn't actually exist.

I am hungry for vol 2 to see how this whole terrible circumstance is resolved and to see whether this will be a great work or merely a good one.

Beverly

Nick Drnaso

136 pages

Drawn & Quarterly

ISBN: 1770462252 (Amazon)

Beverly is kind of like Killing & Dying—only it didn't annoy me.

The Dark Knight Returns

Frank Miller and Klaus Janson (coloured by Lynn Varley)

224 pages

DC Comics

ISBN: 1401263119 (Amazon)

This one is here largely because of its importance to the history and development of the form in the US. For what it is—a yarn in the superhero genre and one dating to 1986—it's an incredible piece of work. It would be more astounding had it been the first time Miller has hit the scene, but he'd been knocking around for a while at this point and you could see DKR's formal tics present in Daredevil and Ronin. But this may be where he best put his aesthetic into practice for a wide audience (what normie was reading Ronin, after all). Addd to that he made Batman actually feel dangerous and a little psychotic, and you can see why (in a world where Batman's otherwise most pop-accessible appearances were in the Adam West television show and the animated Superfriends) this would have been such a kick in the pants for the franchise. Batman Year One downplayed the silliness of the character (though it was still present) and focused on badass Batman; Dark Knight Returns marries camp and badass in such a way that readers can easily forget that they're reading an absurd, campy Batman story. Miller dances this line really well, and dances it well possibly for the last time in his career (everything afterward that I've seen feels like parody). And it really is a pretty book—despite being so dirty and grime-splattered.

The Iron Wagon

Jason

272 pages

Fantagraphics

ISBN: 160699414X (Amazon)

A neat adaptation of a Norwegian murder mystery. Jason picks the right stuff to show and the book feels satisfying even if the mystery itself contains several kind of ridiculous elements.

Boys' Night

Max Landis and AP Quach

29 pages

Self-published

Read here

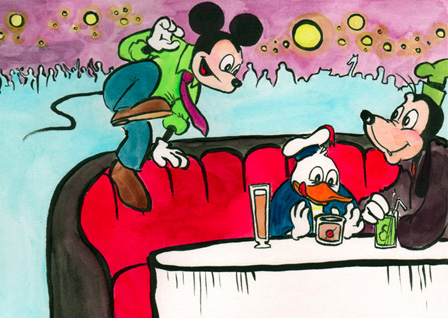

Boy's Night posits a middle-aged Mickey, Donald, Goofy, Minnie, Daisy, etc. It would be easy to mistake the story for something cynical. It's not, but at a glance it might look that way.

Boy's Night is real. It's about what happens to the idols in the cult of celebrity once the sheen is gone. What happens to the souls that have been plastered over for so long that the reality and realness of the lives behind the facade become difficult to even recognize.

Boy's Night is a touch mean-spirited but simultaneously tender. And it's about what it's like to be human in a world beyond our control. The trajectory is made rare by the injection of celebrity, but the story beats and thematic notes are the everyday. Humdrum and mundane.

The comic may look a bit crunchy but it's a real achievement.

Watchmen

Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons

448 pages

DC Comics

ISBN: 1401245250 (Amazon)

Watchmen is important to the history of the medium. And formally, it's brilliant. Moore is meticulous in how he plans his pages, his story, his ordo apocalypsis. And I really do like the pirate parts. But like pretty much everything I've read from Moore, he's more interested in that meticulousness than in pushing me to invest in his characters as anything more than story props. Because of this, despite all the ways in which Watchmen is genius, it also remains largely emotionally inert—a sort of dead thing. It's a good book, but not one that I like, not one I care to read again (four times is enough for me) while so many other books go unread. But hey, I am in the distinct minority on this and so you should probably give it a shot if you haven't already. Of course, if you read it and didn't really enjoy it, don't worry about it and don't feel you need to force yourself. I'm here to validate you.

Knights Of Sidonia

Tsutomu Nihei

15 vols

Vertical

ISBN: 1935654802 (Amazon)

With Blame and Biomega, Nihei showed himself master of the bizarre and compelling. These are books that make you go Wow. With Knights Of Sidonia he dialed all of that waaaaaaay back, crafting instead a rather straightforward (even if evolving) space adventure storyset in a far-off future. Nihei is still wildly inventive, only here he's constrained himself to playing within range of his tropes' boundaries.

The gist: Humanity's been on the run from a bizarre alien species for a mckenna years or so on a giant spaceship (think the SDF-1 from Robotech, if you can remember that far or have been adventurous with your Netflix usage). There are the civilians, the crew, and the immortal crew (who've undergone genetic tampering in order to live pretty much forever, barring catastrophic interference ...like guns). Nagate is the clone of an immortal, invincible pilot from 500 years ago, only his "father" hid him away from society for fatherly reasons and he's only just now rejoining the world. And, as they say, he's got a lot to learn before he's ready to save anybody.

He meets and hangs out with and eventually impresses a lot of women: the ship's immortal captain, the currently genetically-sexless-but-give-her-time pilot cadet, the sister of the woman who died on Nagate's first mission, a talking bear with a robot hand, the ace pilot, the clone sisters, the AI, the alien hybrid genetic daughter of his former almost lover, etc. Knights Of Sidonia is always on the verge of threatening to become a harem manga, but Nagate's complete disinterest in forging romantic relationships and his complete interest in eating and flying mechas subverts what could just be boring business-as-usual.

I'm not specially interested in mecha, but Knights of Sidonia, with its focus on the relationships between its characters and the enjoyable soft-use of hard sci-fi concepts, remains a favourite. It moves between epic spectacle and post-contemporary oblivious harem.

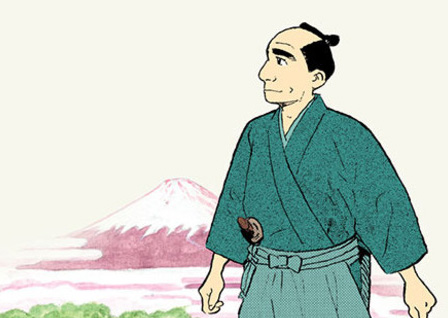

Tokyo Is My Garden

Jiro Taniguchi

152 pages

Ponent Mon

ISBN: 8496427072 (Amazon)

Life is grand for David Martin, Tokyo Is My Garden's protagonist. The people he works with at a fish market shout out his name in welcome. He wows Tokyoites with a knowledge of kanji that is daunting even to natives. He knows where all the best night spots are. And though he might have just been thrown out of his girlfriend’s apartment (she was a model), he’s quickly picked up a new one (a slick business professional who might as well be a model). He may have troubles, but none of them have to do with his reception by the people of Japan.

Playing to type, David’s one constant thorn relates to his own native land. Generally, the Westerner who dreams of exotic success in Japan is someone whose life in the West isn’t panning out glamourously. It’s like the kind of dorky kid in junior high who’s not even in the running for being considered popular—he imagines that if he’d only move to a new school, that’d be his big chance to rewrite his fortunes. When that kid grows up a little, he’ll recognize that just changing schools isn’t enough. He’ll need to go somewhere where his novelty won’t wear off in the space of a single day. He’ll need to go somewhere where he’ll naturally stand out. And if he’s white, then Japan is a natural destination candidate. Sure, he could go to Kenya, but he’s a little bit uncomfortable with all those black people. He could go to Peru, but he doesn’t remember seeing any Peruvian comics that go out of their way to show off teenagers’ panties, so… Japan it is. I mean, fraught with biases and misconceptions as he is, it might as well be Japan—which he doesn’t actually understand any better than he does Kenya or Peru or even his own high school’s cultural pool. And he’ll be fine so long as his old school doesn’t come back to haunt him.

David is haunted by his real job and the ostensible reason he’s in Tokyo to begin with. He’s a sales rep for a small French firm that produces brandy. He’s been in Tokyo for three years, supposedly learning the lay of the land and preparing contacts and hocking the company wares. Only: he’s really only majored in girls, parties, and studying kanji. His boss is set to arrive in three weeks to evaluate his performance and he has yet to sell a single bottle of the product. He’s worried that his dream could vanish, that his celebrity could be left behind while he’s dragged back to France. It’s a hard-knock life.

While Tokyo Is My Garden is the story of what will happen to David and how on earth will he pull out of this scrape, it’s also the story of a dream. This book is the compiled navigation charts for a group fantasy. David is kind of really completely obnoxious in that he’s living the life so many nerdy young white males would drain the blood of virgins for—and worse, he deserves it as much as they do. He’s kind of losery, kind of a bum, kind of not the kind of person you’d expect to be rolling in models. Unless you’re the very particular kind of person who could find Boilet and Peeters’ story remotely believable.

It’s a strange mix. Boilet has made it his goal to produce nothing that is not taken from reality. As we saw in Yukiko’s Spinach, his images are drawn from video footage. His poses are realistic and his figures are believably proportioned. And yet, his story must take place in a dreamworld. David Martin is the envy of Tokyo and he does nothing to merit that goodwill save learn the language. It’s preposterous. Then again Boilet, who is a cartoonist and not a rockstar, takes video of all sorts of things that the average joe probably couldn’t imagine taping. All for his drawings, sure, but nonetheless: if a cartoonist can experience that degree of worldly hoo-hah, then perhaps David Martin’s story isn’t so wholly unbelievable after all. Score one for the white and nerdy.

Happiness

Shuzo Oshimi

7+ vols

Kodansha Comics

ISBN: 1632363631 (Amazon)

Shuzo Oshimi, the nutball (in an awesome way) behind Flowers Of Evil, Inside Mari, and Trail Of Blood) is putting out maybe the first vampire story that's caught my interest. There's a solid mix of stuff common to the subgenre *and* stuff that is more in line with Oshimi's unique set of interests.

Beyond the many weirdnesses at play, Oshimi draws the heck out of the book. He sometimes veers into straight-up surrealism when depicting the experience of his vampiric characters—and it works colossally well.

Welcome To The Ballroom

Tomo Takeuchi

11 vols

Kodansha Comics

ISBN: 1632363763 (Amazon)

This is a sports story and one of those sports stories about the prodigy player who got a late start on the sport and is going to quickly make up for lost time because he’s that good. It’s a common enough formula, but Welcome To The Ballroom performs its steps very well. It’s graceful on the fundamentals while throwing in some delicious variations for a pizazz that serves to elevate the rest of the story. In the five vols I’ve read so far (I’m enamoured enough that I plan to continue with the series as new vols are released), fifteen-year-old Fujita moves from entirely inexperienced amateur to gifted would-be competitor. He begins the series aimless and struggling to find an interest as he is being pushed to choose a high school to attend. Accidentally, he finds himself in a dance studio with members devoted to competitive ballroom dance. While initially embarrassed and hoping nobody discovers him there (male dancers have about as great a reputation amongst other teens in Japan as they do here), Fujita sees a video of what competitive ballroom dance is actually like and in set alight. He has a direction now and will rocket toward it through the rest of the story, meeting obstacles and overcoming them or using his defeats by them to improve himself. (See? That sports story formula. AKA life story formula.)

If you’ve read sports manga before, you’re probably familiar with the story beats, but where Welcome To The Ballroom shines is in its visual depictions of athleticism. In Polina, Bastien Vivès ably depicted his ballet dancers in spare, minimalist gestures, giving the dance a quiet fluidity emphasizing the grace and beauty of the form. Welcome To The Ballroom doesn’t remotely attempt this. Takeuchi’s dancers are vibrant, bursting with frenetic energy. They are electric and exciting and Takeuchi draws flourishes to highlight some of the emotional energy exploding beneath the skin. Fire will crackle off the clasped hands of a couple as they waltz. A character will be engulfed in flame to express his rage or passion. The skin of another will bristle and steam as their waning strength rejuvenates to pull out one last showstopper. And the sweat.

Takeuchi does one thing I’ve never seen in a comic about active characters before. They are drenched in sweat. Rivers of it pour from their hairline down their faces as they exert themselves. It’s an incredibly small detail but it goes so very far in selling the world of these competitions. The beautiful, gorgeous women in this book do not glisten. They sweat. Buckets. It’s perfect and real.

So far at least, Welcome To The Ballroom doesn’t escape its tropes or formulae, but it’s not trying to. Instead, the book is playing entirely within the established realm and doing so with verve. It’s nailing all the steps and avoiding many of the pitfalls. It’s sweeping across the floor getting it done and showing how to do it. Welcome To the Ballroom doesn’t have the emotional range or sweep of Cross Game but does make its sport thrilling even for those, like me, who don’t have much actual interest in the activity depicted.

201–210211–220221–230231–240241–250

251–260261–270271–280281–290291–300

March Of The Crabs

Arthur De Pins

3 vols

Archaia

ISBN: 1608866890 (Amazon)

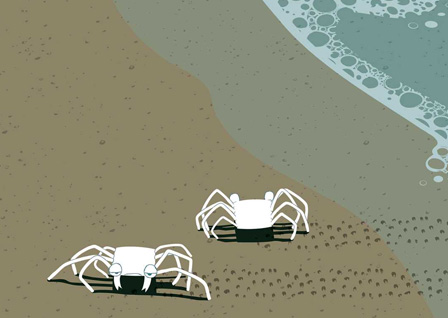

March Of The Crabs concerns a particular species of crab (that I'm not sure actually exists) that is small, has no predators, and cannot turn. These little guys can only move side to side with no deviation. So, for the duration of their lives, the walk back and forth along the single vector into which they were born (barring external acting forces, like a wave or something). A crab who finds herself fancying a crab she walks parallel to will never have the opportunity to touch that crab.

Sad life.

Having no predators and being outside the food chain, these crabs have never had the need to evolve. But now, this one crab has an idea, one that will begin a change across the race. He hops on the back of a crab going perpendicular to his own path and through teamwork, they can travel anywhere along that x and y coordinate grid. And there are more surprises in store for the species—and all the political turmoil that naturally goes along with that kind of thing.

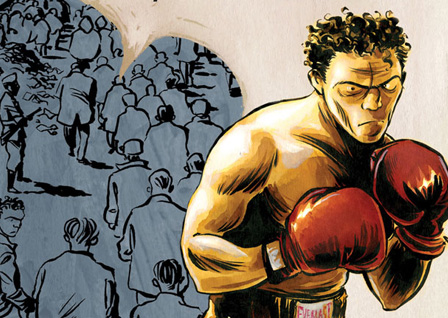

The Boxer: The True Story of Holocaust Survivor Harry Haft

Reinhard Kleist

200 pages

SelfMadeHero

ISBN: 1906838771 (Amazon)

Harry “Herschel” Haft spends significant portions of his life being identified by his past. Even as he prepares to disembark onto American shores for the first time, Harry is overwhelmed by turbulent visions from his time in front of Nazi ovens. Inconspicuous moments are haunted by the memories from which his own personal history snakes out to grip him by the throat, offering both paralysis and catalyst. This is Harry at his most American. Occasionally spurred by a kind of romanticism and glimpsing a self he hoped to one day inhabit, Harry throws himself into his boxing—all to the end of finding again the love of his life and making true the faery tale. Only by beating and clawing at the lives of others will he be positioned to take on the identity he dreams for himself. This is Harry at his most American. Finally, the boxer surrenders his dreams to what he imagines must be reality. He takes up a new daily struggle and throws himself into the most immediate of concerns: food, shelter, companionship, progeny. His dreams no longer control him, his past no longer commands him. He is wholly devoted to the now. This is Harry at his most American.

Though of course it isn’t all so simple as that. Even while Harry is who he is in the present, he cannot shake the ghost of the past—ghosts that twist his dreams for the future. The former boxer is harried by the life he once hoped to live and those dreams built of a busted prescience only work to diminish the identity he finally settles into. He’s a man torn at by invented creatures beyond his control, and he is weak in the face of them. Yet simultaneously, this man—this boxer—is full of spit and fire and fight. And that’s actually where half the wonder of Kleist’s work resides.

The Holocaust tale is one of broken hearts and spirits, of human persons reduced to walking ghosts. It’s terror after terror and it breaks everyone, rendering them into the soulless. Beyond even the deaths and murders and rapes and incinerations and gassings, probably the thing that devastates me so entirely is the iron work of destruction the Nazi machine wreaks on the souls of their victims in these stories. Perfectly believable, sure; yet not something I want to see more than a handful of times. Haft, however, is a pugilist. And even if he isn’t yet a boxer when he gets dragged to the camps, he’s born a fighter. He’s got spirit and its nigh unquenchable. The Nazis will go to great lengths to diminish Haft, to strip him of his inner fire; they will essentially destroy him and ruin him for all time. But it will take something greater than Hitler’s mania to turn Haft into the living dead. Because he fights and fights and fights.

Even when he establishes himself in the US boxing circuit, Haft makes certain his boxing trunks are decorated with a Star of David. This could easily be seen wholly as a redemption and repurposement of the star that was used to damn the Jews not even a decade earlier, but there’s more to it than just that. The five-pointed pentagram, associated with Daivd’s royal son, is called the Star of Solomon; it’s the hexagram that is David’s star. And while both kings, Solomon and David, carry their measure of historical fame in the Jewish mythos, David was the warrior—so bloody-handed and vicious in battle that he was forbidden from building a temple for Yahweh by Yahweh himself. Solomon’s reign, on the other hand, was marked by peace, prosperity, and leisure. Solomon’s star could never suit Haft for Harry is every bit the tortured warrior and fighter that King David would have been.

So when we see in The Boxer's opening pages that Haft is broken and crazy, we are driven to find out why. It’s a perfect opening, especially as Kleist immediately juts back to fourteen-year-old Harry (then named Hertzko), full of piss and fire and life. It’s a fantastic setup and by the time Kleist catches us up again to the Harry Haft revealed in the opening pages, it all clicks. We’re sold entirely on the tragedy and victory of his life. All things have come to resolution and we are satisfied.

Palomar: The Heartbreak Soup Stories

Gilbert Hernandez

520 pages

Fantagraphics

ISBN: 1560975393 (Amazon)

This is an expansive experiment, following a huge cast of characters through a nearly madcap existence in a small Mexican village over the course of decades. People live, die, are born, leave, and love. Taking any single story from the collection feels like a weakness. These stories grow and become stronger by their proximity to one another.

Biomega

Tsutomu Nihei

6 vols

VIZ

ISBN: 1421531844 (Amazon)

Marking the boundary in Nehei's development between his scratchy manic style in Blame and his ultra-crisp austerity in Knights Of Sidonia, Biomega sits both as an interesting artifact and a valuable work in its own right. The first half feels like a high-octane romp much in the style of Blame, where you have a ridiculous sort of human dude with ridiculous tools plowing through opposition forces. Then, about halfway through, the shackles get blown off and things just go straight bonkers. And also, his aesthetic because to clean up. Like Blame, when it's all wrapped up, you're sitting there going Wait, what? And then you sit on it, reread the last volume or maybe the whole book, and then you come to a place of peace with the story maybe. Maybe you look online for theories, for interpretations. And maybe it all starts to coalesce for you. Maybe. But in the end it doesn't really matter how you felt in the end because man what a wild ride!

Age Of Reptiles

Richard Delgado

4 vols

Dark Horse

ISBN: 1595826831 (Amazon)

Silent comics are really difficult to pull off well. They’ve got a lot going against them. Exactly half of the linguistic repertoire being forbidden, the creator is forced to rely wholly upon visual language for all exposition. When characters cannot exposit their own motives to the reader, they must rely on illustrated cues to make their purposes, intents, reasons, and passions both knowable and then known. And as difficult as that sounds, the requirement upon the artist of these characters is phenomenal. Not only does the artist have to reliably draw characters recognizably and convey story through panel-to-panel storytelling transitions (as is the case even in comics featuring dialogue and narration), but beyond this, the artist must be able to convey all those burdens generally carried by the writer of words. Personality. Interaction. Interrogative. Exclamation. Thought. Emotion. Reaction. Success in these tasks takes the hand of a master.

In his third book in the Age Of Reptiles series, The Journey, Ricardo Delgado reveals a magnificent work of dinosaur fiction. Fourteen years after he began the series, Delgado’s come to a design and illustration sense that is easy on the eyes, powerful in communication, and still adept at conveying the wonder of the earlier series’ best moments. His work is still incredibly detailed but shows a marvelous sense of restraint, allowing abstraction where needed. As well, there are moments such as a partially devoured anklyosaur floating in a river that are magnified by Delgado’s talent with framing and negative space. What may be most jaw-droppng in “The Journey” is just how many dinosaurs Delgado draws on every page. His story calls for it for sure, but it’s still a minor wonder to behold.

Where The Journey also excels over the prior two series is in story. To illustrate, however, I’ll have to complain about something central to the earlier two books.

The reason, presumably, that Delgado chose to make Age Of Reptiles a silent work is that dinosaurs are not people. They presumably have little facility for language and if they did and we could translate it, their way of conveying meaning might be so alien to us that we wouldn’t understand anyway. My guess is that this book was made wordless in a bid for realism.

The problem, if realism is Delgado’s reason for not verbalizing anything, is that the first two series (Tribal Warfare and The Hunt) are built almost entirely on personification. Tribal Warfare features a grudge between a family of T-rexes and a family of utahraptors (I think they’re utahraptors). The lead tyrannosaurus scares the raptors off their fresh, rightful kill and initiates a back-and-forth war of attrition that lasts four chapters and ends in all-out battle. It’s a fine story but not a fine dinosaur story unless you want your dinosaurs fixed with embedded human motivation. The Hunt follows a young allosaur as he flees from the murder of his mother by some wildly coloured raptors. Their pursuit of him lasts for what seems years. Long enough at least for him to grow to full-size. Both the raptors’ dogged pursuit of the allosaur despite there being far more docile game everywhere and the allosaur’s plan to revenge himself against them left me incredulous. I couldn’t be sure why Delgado didn’t just give these animals voices if he was going to give them human motivation.

The Journey solves this problem in two ways. The first is that Delgado gives no opportunity for these reptiles to act in any way other than as the animals they are. The other is that The Journey is not the story of a dinosaur protagonist but instead the story of a massive migration. I’m reminded of Planet Earth's segment on the migration in Africa toward the Okavango Delta. Delgado depicts a collection of herbivore dinosaur herds moving from arid lands toward a lush forest. Their way is perilous and they are followed closely and picked at by predators. If there is a protagonist at all, it is the combined herd, striving forward while being winnowed and whittled. It’s magnificent and I’m so very glad that Delgado chose this direction for the third series.

The one sadness is that Age Of Reptiles isn't collected into a gorgeous oversized hardcover. It isn't even collected in a standard-sized trade paperback. Instead it's bunched into the back of a perfect-bound manga-sized omnibus collecting the first three Age Of Reptiles series. The Journey is a book that deserves space and room to breathe. It would have made a great 13"-tall hardcover, like those ones that Nobrow was doing a while back. The one bright spot of this development (beyond that the book exists at all) is that you DO get to see the earlier two series and marvel at just how well Delgado has evolved as an artist and storyteller.

Dotter Of Her Father's Eyes

Mary M. Talbot, Bryan Talbot

96 pages

Dark Horse

ISBN: 1595828508 (Amazon)

In this both biographical and autobiographical work, Mary Talbot (aided visually by husband and illustrator Bryan Talbot) confronts the struggle of society to lurch into the era of modernity and beyond. It’s unclear whose story Talbot is more interested in (or if she even has a preference), but she introduces an inclusio whereby she in the current day finds an old ID card belonging to her now-deceased father. Inside the framing device Talbot pursues two narratives: one concerning her own formative years at the hand of her father James Atherton, a well-regarded Joycean scholar, and the other charting the development of James Joyce’s own daughter Lucia and the relationship he had with her. Neither relationship is a thing of joy and beauty, but one suspects that if both girls were born to the same fathers a century later, the absence of certain social constriction might have allowed for happy endings all the way around.

As delineated by Talbot, both Mary’s and Lucia’s lives are welled up under the pervasive irony of being the children of bastions of modernism who cannot see clear to apply modernist principles to their own patriarchal relationships. Dotter lays special emphasis on the rallying cry of the paradigm movement: “How modern!” Everyone around both Mary and Lucia are caught up in the transformation of culture—of the evolution of the stilted, errant, grossly conservative pre-modern society into the glorious fortress of progressive social democracy found in the modern utopia. It’s a period of hope and change. And each of these two fathers are in some sense heralds or ambassadors or representatives of this new civilization.

The irony of course is that in the cold darkness of their hearts’ hearts, they are still staunch defenders of the Old Ways—hopeless, helpless relics who will unconsciously stop at nothing to crush the Spirit of the Age in its most immediately tangible bastion. They will carelessly destroy their children (or perhaps die trying), unaware that in so doing they make mockery of those values they pretend to hold dearest to their hearts. Mary’s father Atherton will do so by his direct actions built of disdain and outright dismissiveness of his daughter. Joyce, on the other hand, will combat his own values through a negligence in policing he and his wife’s failure to recognize Lucia as something more than their provincial understanding of the female being will allow.

“Sad life. Sad life,” to quote a certain wise but immolated horse.

RASL

Jeff Smith

4 vols

Cartoon Books

ISBN: 1888963379 (Amazon)

Jeff Smith’s RASL is sometimes billed as sci-fi noir but is really only sci-fi that’s influenced by noir. And that’s okay. It’s okay because, for the most part, the book is really good. And at the end of the day, even if the thing you want more than anything is Billy Madison 2, you’re still gonna be pretty happy if you get Last of the Mohicans instead. Apple? Orange? Who cares so long as it’s tasty and refreshing.

One of the most immediately discernible positives about Smith’s book is the art. If you were a fan of Bone's illustrations, you’ll be right at home in RASL. My young daughter saw me reading the book, looked inside, and asked if it was a new volume of Bone. She’s three-and-a-half and she could pick out Smith’s style at a glance. He’s built the book around the same strong use of positive and negative spaces, the same fine-lined figurework and exaggerated postures. And just like Bone was dominated by beautiful pages, so is RASL—even if the New Mexican desert isn’t half so lush as Thorn’s Valley.

Like his prior opus, this new work allows Smith to explore the divide between the visible and the spiritual, between the empiric and the elusive. The scientist-on-the-lam hero, Rob, is caught between mysteries his methodologies have a chance at explaining and the myths that roam his world unheeding the requirements of physics or the natural laws. He encounters the god he trusts, Nikola Tesla, through diaries, journals, and academic papers. He blunders into a god he’ll never understand through simple acts of providence. Whether he encounters the divine or not is something that Rob is not equipped to discern. And in the end it doesn’t really matter. After all, this is a thriller, dammit, and Rob’s trajectory and the conventions of his narrative will not allow us to dwell overlong on philosophy or metaphysics.

We can’t forget that Smith is modeling Rob’s journey on the comfortable formulae so native to the noirish mode. Rob’s a dirty angel, but he’s our angel. He’s morally tarnished (and was so even before he went off the grid to flee a government bent on information and revenge), stealing art and shacking up with a prostitute. He’s a man of deep appetites and his use of Tesla-inspired world-skipping technologies only serves to enlarge his antiheroism and needs.

And as much as he’s caught between science and spirit, Rob finds himself wedged between any number of other duets. Some abstract, others less so. Tormented by the ghost of a scientist and the ghost of a woman. Crushed between his rational mind and his hungering passions. Full-bodied romance and the stale whiskey of base desire. Selfishness and sacrifice. He’s the hooker with a heart of gold, only he’s selling his soul instead of his body. He could be a character out of Chandler if only he had a chance with the snappy patter. He’s hard-boiled alright, but not much of a talker. He’s closer to John McClane than he is to Philip Marlowe.

Zita The Space Girl

Ben Hatke

3 vols

First Second

ISBN: 1596434465 (Amazon)

One of the biggest joys of the last several years has been all the notes of thanks I've received for recommending Ben Hatke's Zita The Spacegirl. Little emails, tweets, vines (when those were a thing), instagram photos tagged to me, people stopping me in Starbucks. Pictures of kids holding up Zita The Spacegirl. Video reviews with kids saying how good the books are and thanking me for recommending them. Stories of little girls going to sleep clutching a volume. It's amazing, and playing a part in kids finding a story to inhabit fills me with a tremendous sense of joy.

Zita The Spacegirl is a very good graphic novel series. And it gets better with every volume. When kids get to the third volume, it knocks their socks off. Zita the Spacegirl (and its follow-ups) relates the adventures of a reluctant hero, Zita, a girl sucked from our end of the galaxy to another end of another galaxy. It’s Homeward Bound: The Incredible Journey—only instead of two dogs and a cat, it’s just a lone lost girl who becomes something bigger than she is. And it is a superb read for kids, and probably pretty fun for grown-ups.

And really, as much as I love hearing about how much these children love Hatke's books, the thing I love most about Zita The Spacegirl is how much my own daughter loves the series. Just as other children do, she has often been found sleeping with one volume or another of the series. Her fourth birthday party was themed around Zita. She renamed my wife Strong Strong, just because. She wanted me and her to somehow learn to fly so that she can be Five and I can be Eight for Halloween that year. And that was all before she found out that the third volume was coming out.

Somewhere around the Christmas before it released in May (five months later), I told her the news: that the third and final book in the Zita series was coming in a few months. She was awestruck. She couldn't wait. And then I suggested the impossible—that maybe, if she worked really hard, she might be able to learn to read in time enough to read it to me instead of the other way around. And that was all it took. My four-year-old daughter was alight and spent the intervening five months trying to learn to read. She had "school" every day with her mother, learning letters, learning phonemes. She demanded to learn. I was blown away by the determination Hatke's series has inspired in my daughter. By the time the final book came out, she was reading sentences and pointing out the names of stores on signs. At the beginning of that April when I told her that The Return Of Zita The Spacegirl would come out in a month, she asked if I could make it wait eight more months so that she could be totally and completely ready. She loves Zita's story so much that she's willing to put in an hour of work every day of her own initiative—just for the potential joy of being able to curl up with the book whenever she wants and not have to rely upon either another reader or memorization. I would love any book that could open the floodgates to the whole history of narrative excellence to one of my children. And so I love Zita The Spacegirl. Not only for the very cool little space adventure it is, but for the lifetime of Story that it initiated for my daughter.

Audubon, On The Wings Of The World

Fabien Grolleau, Jeremie Royer, Etienne Gilgillan (translated by), David Sutton (translated by)

184 pages

Nobrow

ISBN: 1910620157 (Amazon)

Audubon is a sumptuous book, filled to brim with illustrations of forests, rivers, animals, and birds. It was a delight to discover the mania that lit the life of John James Audubon, a man of whom my only prior knowledge was his connection by name to the Audubon Society.

It's a well-paced jaunt through the man's later life, dwelling on episodes that confirm his infatuation with nature, his love for it, and his need to catalogue it. It's also interesting to see the 19th century environmentalist for how vastly different they are from their contemporary counterparts. In the 200 years ago, the environmentalists were hunters and one of their best tools for securing assistance in unveiling the natural world to the public (and eventually protecting it through parks and reserves) was to kill lots of animals and display them. This was Teddy Roosevelt's M.O. as well.

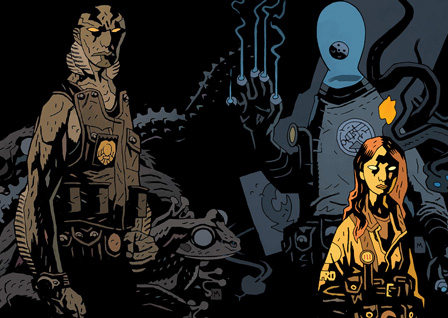

BPRD

Mike Mignola, John Arcudi, Guy Davis, Tyler Crook et all (coloured by Dave Stewart, lettered by Clem Robins)

30+ vols

Dark Horse

ISBN: 1595826750 (Amazon)

Spin-offs are always a bit of a dicey proposition. For every well-received Frasier or Rhoda, there are many more that fail to capture that spark of interest that dazzled the audiences of their progenitors. The Tortellis, Just the Ten of Us, Joey. Every spin-off is something of a funambulist and over a variety of perils there are these fine lines they must traverse. Beyond the normal gamut of ways in which a new series might fail, spin-offs have additional baggage threatening. Too derivative. Not derivative enough. Under-developed characters. Too deep in the shadow of the original.

Still, in some cases, a spin-off is the only way in which to preserve well-loved supporting characters when their series turns in a new direction. Such was the case for the cast of BPRD. While long at home in the pages of Hellboy, Abe Sapien, Liz Sherman, Kate Corrigan, and the mononymous homunculus Roger (each members of the Bureau of Paranormal Research and Defense) were left lurched in the conclusion to “Conqueror Worm.” Hellboy, discouraged by the duplicity with which the Bureau had treated Roger, leaves the organization to pursue a more personal venture. The series Hellboy at this point cuts ties with the BPRD and, more importantly, with Abe, Liz, and the others. Hellboy becomes a book with a cast of one.

The only problem here is that Hellboy’s BPRD cohorts are great characters and readers want to know what happens to them. Behold the birth of BPRD, the series.

I was nervous. I loved these characters. Kate was as yet underdeveloped, but Abe had a rich history to be explored, Liz’s inner struggle was left unresolved, and Roger was just fun. I wanted BPRD to be as awesome as Hellboy was. I wanted this spin-off to be the exception to the rule.

And then I read the first arc, "The Hollow Earth," a story delving into a neat piece of 19th century fantasy lit legend. It fell flat. The story (with three writers) struggled to find its feet. The elements were there, but the tone was off. Ryan Sook’s art was accomplished but felt too much like an aping of Mignola’s work on Hellboy. When I first saw panels from the book, I thought Sook would be a good fit, taking over where Mignola left off. It didn’t work out.

The next group of stories caused my fears to grow. A series of one-shots, each featuring a different artist/writer combination, almost wholly failed to do anything worthwhile with the Bureau’s peculiar agents. There was one exception. “Dark Water,” written by Brian Augustyn with art by Guy Davis, was the perfect mix of who the BPRD should be and what the series could be. I suspected that it was Davis’ art that really sold home this vision of the book. Sadly, “Dark Water” came early in this series of short stories, so by the time the next arc began, I was ready to bid farewell to the Bureau and to characters for whom I no longer cared.