This is picks 101-200 of Good Ok Bad's Top 500 Graphic Novels Of All Time. Follow the links below to get elsewhere in the list.

101–110111–120121–130131–140141–150

151–160161–170171–180181–190191–200

My Best 500 Comics Of All Time (101-200)

Far Arden

by Kevin Cannon

382 pages

Published by Top Shelf

ISBN: 1603090363 (Amazon)

Comedies are ridiculously difficult to pull off over the long haul. Generally, their shtick gets a little long in the tooth well before the halfway mark and the same would have held true for Far Arden had it not gradually developed into a compelling story with decently well-realized characters.

Following Army Shanks, a man “as cold and unforgiving as the Arctic herself,” author Kevin Cannon treats the reader to a bizarre journey through arctic locales and jaw-dropping onomatopoeia. Shanks makes his way through fishing villages, queer universities, and frozen islands (which apparently actually exist in that nefarious and frigid land known as Canada) along with an entourage of friends, enemies, and former friends and former enemies. All to the end of finding Far Arden, the mythical island whose discovery has devoured (and will devour) the lives of almost every principle character in Cannon’s book.

Throughout the book Cannon skirts the border of believability, never quite falling into a world that jibes with reality, but never going so far into fantasy that we don’t understand there are certain mortal rules common to both our reality and his. Relationships tack as they do in our world, those mauled by polar bears don’t get up, and ambition can kill. That said, there are golden narwhals that will direct willing sailors to paradise. So you’ve got that going for you.

For those curious about the art style of the book, Kevin Cannon apparently began the book as part of an extreme 24-hour comic experiment—instead of creating a whole 24-page comic in a single 24-hour sitting, he would perform a year’s worth of these sittings monthly to create a single, large book. That lasted for four months, so each of the first four chapters were created in a discreet 24-hour period. After that, he adopted the same style but slowed down his pace to one chapter per month—though not in a single sitting. (I believe the additional time spent shows.)

Uncomfortably Happily

by (translated by Hellen Jo)

576 pages

Published by Drawn & Quarterly

ISBN: 1770462600 (Amazon)

I complain a fair amount about autobio, because often (probably even usually) it's obtuse or aimless or doesn't really have any real narrative trajectory. Also, unless the author is very specific in their aims, the work meanders and really isn't about anything beyond scattered snapshots of a life lived with little sense of understanding What Actually Happened. A lot of this can be mitigated by choosing a succinct pericope and essentially making your autobio comic about The Time I Did This And This Happened And Here's What I Got Out Of It.

When I first picked up Uncomfortably Happily, I winced to find it was autobio. At 576 pages, aimless navel gazing for the duration might actually kill me. Fortunately, Hong gets it. He knows what he's doing and does it well.

Hong and his wife are artists. Hong has been in comics for 14 years and his wife, a former student, is just attempting to get her career off the ground with a couple quirky children's books. They get fed up with the cost and chaos of life in Seoul so they move to a remote house up on a lonely mountain if order to work more freely. Uncomfortably Happily is the story of the year they spent there, what happened, and how it changed them.

We see their joy and interest in the move, Hong's early budding reticence, and their realization at just how much work living provincially will cost. We see how each deals with the loneliness, how cold and hard winter can really be, and how Hong begins to lose his freakin' mind. And then we see the rest of it.

Beyond the fact that Hong tells his story well, there were two principal things I deeply appreciated.

1) We see intimately Hong's struggle as an artist desiring to do work he considers valuable and of merit but needing to take on other people's contract work in order to keep the phones on and the house heated (spoiler: these things don't always get done). There're a lot of moments when there are two or three Hong's on panel talking with each other, arguing about what to do or how to live. Hong feels like a failure, constantly fielding revisions from his editor on books that never see substantial royalties. As an artist myself (and comics artist) who struggles to find time to work on my own projects and makes ends meet in graphic design, I found many moments of myself in Hong.

2) As Hong (the character in the book) gets sick from burning candles at weird ends and his depression and anxiety and anger at life overwhelm him, Hong (the author of this story) dives into non-literal representations of things. Animals talk, his comics come to life, things get kind of crazy. It was an unexpected direction and it elevated the work for me to see him portray his inner struggles with such fancy.

There might be something better out there, but for my money so far, Uncomfortably Happily is the best comics autobio of 2017 by a pretty wide margin.

The Gigantic Beard That Was Evil

by Stephen Collins

240 pages

Published by Jonathan Cape

ISBN: 1250050391 (Amazon)

All stories are necessary lies, says Stephen Collins' narrator. And also, the point of everything seen is to keep hidden the unseen. So stories then must serve two purposes, to hint at that which is hidden WHILE further obfuscating what lies beneath.

As fable, or better as parable, The Gigantic Beard That Was Evil accomplishes both of these things, hinting at the hidden by critiquing the visible (society and its common—and often celebrated—artifices) and simultaneously being vague enough that you can't quite make out exactly what it wishes to unveil. It, in a sense, allows you to pick your target.

TGBTWE is Stephen Collins first graphic novel. It doesn't show. The book is a masterpiece and certainly a part of the 21st century canon were there to be such a thing. The narrative flows well, the script both smart and crisp, the page design a formalist's Christmas, and the art lovely to look at. The book is a joy. It might even be stunning.

Stand Still Stay Silent

by Minna Sundberg

4 vols

Self-published

Read (here)

Post-apocalyptic zombie fiction has never been better. Which is good because the post-apocalypse is pretty well played out and man do I hate zombie fiction. But Sundberg's vision here is almost entirely unique in every way.

1) The remaining civilized world is so far limited to Iceland, fortified pockets of Norway, Sweden, and Finland, and a single island of Denmark. That's a rare and interesting setting for a story told in English.

2) The zombies aren't zombies like we typically think of zombies. There're also corrupted beasts and now a bunch of super-interesting ghosts. And an eight-legged horse that's kind of a ghost boss thing. The lore of this new world is extensive, detailed, and imaginative.

3) Sundberg's art is gorgeous. It's luscious and the way she affects mood through colour is essentially like nothing I've seen.

5000 Kilometers Per Second

by Manuel Fior (translated by )

144 pages

Fantagraphics

ISBN: 1606996665 (Amazon)

A boy and a girl and their relationship to and apart from each other evolves over both distance and time. A story about the way we are broken and can break one another and whether there might be solace regardless. Beautifully painted.

Powers

by Brian Michael Bendis and Michael Avon Oeming

15 vols

Image/Icon

ISBN: 140128745X (Amazon)

Despite some occasional but pretty serious problems with page design and a publishing concept that's just bizarre (vol 15 and 16 retitles the series as POWERS: THE BUREAU vols 1 and 2, then vol 17 is POWERS vol 1)—despite that, POWERS is a solid series, one of the long-running gems of the form. In a way, it's kind of ALIAS before Bendis invented ALIAS.

The basic idea: Walker used to be a AAA superhero back in the day. Now that he's lost his powers, he's a homocide detective, one of a few who specialize in murdered superhumans. He and his new partner Pilgrim investigate crimes, murder-of-the-week fashion until the story really gets going. At that point, status quo is out the window and things go from bad to crazy to worse to maybe a little beter to are we in hell to not quite but maybe next week.

The whole thing is wild and interesting and probably the best thing Bendis has done since ever. I loved his DAREDEVIL, ALIAS, and ULTIMATE SPIDER-MAN, but POWERS is something special. I wish Bendis and Oeming had the time/circumstance/inclination to prioritize this into a monthly title so we could get to its conclusion sometime reasonable. Like maybe he could take 2 years off from Marvel/DC shenanigans and just script the whole rest of the series and then turn Oeming loose on it. It's coming out at nearly Lutes/BERLIN levels of graduality.

The Motherless Oven

by Rob Davis

160 pages

SelfMadeHero

ISBN: 190683881X (Amazon)

Motherless Oven is one of those wild, bursting-with-imagination stories. Davis crafts a world that we'll never be able to expect or entirely grok the rules for. It's funny and turbulent and only ever hints at what it is itself all about. And I liked it for that. It's a world where children, whose origins remain veiled, build and maintain their own parents, know the day of their deaths, and can change the season with an ill-advised flick of a switch.

The book traffics in absurdity but ties it together with a strange sort of ruleset (known wholly by Rob Davis alone, if even him).

Two Brothers

by Gabriel Bá and Fábio Moon

232 pages

Dark Horse

ISBN: 1616558563 (Amazon)

Two Brothers is foremost a book to be laid on a coffee table so that guests will have something astounding with which to occupy themselves while you futz around in the kitchen preparing exotic teas and fancy adult beverages. It is a work of beauty. Dark and grueling, yes, but beautiful for all that. Bá has always held a little dynamo of the kind of expressive shadowed minimalism that makes Mike Mignola's art the most magnificent stuff to ever grace the earth, and the choice to publish Two Brothers without colour forces that to be on full display. There were pages I stared at overlong just trying to understand how they were accomplished.

As for story, Two Brothers won't likely have you asking existential questions about faith and purpose and meaning. It is, instead, pretty firmly rooted in the pre-20th century family of novels dedicated to charting the collapse of a family or dynasty. From its first pages we know where things are headed and our goal is only to lend an ear while the fall of the house of Halim is laid out like funeral clothes, that we too might mourn the passing of a well-meant but ultimately self-destructively selfish family.

House of Penance

by Peter J. Tomasi, Ian Bertram, Dave Stewart

176 pages

Dark Horse

ISBN: 1506700330 (Amazon)

Man. This thing was an incredible experience, mostly from the art but the writing made room for the art and that's respectable. It's gorgeous and grotesque.

It's basically hyperrealized biography of Sarah Winchester (of California's famous Winchester Mystery House). The barebones of the history is that Sarah Winchester married into one half of the Winchester Repeating Arms ownership. Her husband and 5yo daughter died and she kind of went a little haywire with depression, moved out to San Jose, California and started work on a house (possibly to comfort the spirits of a) her husband and daughter and b) the spirits of those slain using Winchester guns. She spent basically $23K a day building, tearing down, and rebuilding the great house (at its height, possibly 7 stories, but after the SF quake only 4). There are doors and staircases that lead nowhere.

Tomasi and Bertram embellish the legend and make her truly bonkers but also sympathetic. The book is deliriously full of hallucination and visual metaphor. It was a wild ride.

Strangely, though, they got the year and age of her death really wrong.

The Neighborhood

by Jerry Van Amerongen

daily strip

Andrew McMeel

ISBN: 0836218469 (Amazon)

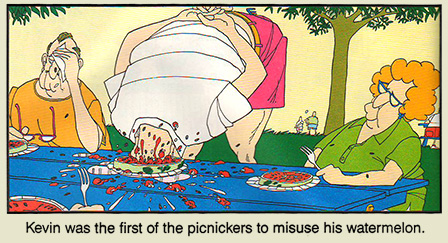

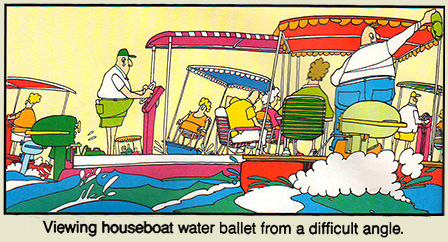

I mentioned earlier how Calvin & Hobbes came on the seen and gave me a new place to hang my hat as a religious reader of the daily funnies in the LA Times. Well during that same time, I'd become hip to the absurdist wonder of Jerry Van Amerongen's The Neighborhood, each day a single panel gag revolving around the eccentricities of some random member of the community (there were no recurring characters). Some examples:

I'm not sure who the actual intended audience for these was but I know that as a 6th grader, I was in love. His bizarre human shapes, his lovely sense of humour, his way of rendering pretty normal things as obscenely strange but then rendered again normal by the reactions of the sighing, eye-rolling, put-upon members of the neighborhood. It was all perfect for me then, and honestly, it's perfect for me now too.

101–110111–120121–130131–140141–150

151–160161–170171–180181–190191–200

Sakuran: Blossoms Wild

by Moyoco Anno

308 pages

Vertical

ISBN: 1935654454 (Amazon)

Moyoco Anno’s book is about women in distressing circumstances, and throughout I felt the weight of the whole history that has arrayed itself against the female existence. I think of my wife, my daughter, my mother, my friends, women I know from the internet, and women I don’t know at all and will never know. Societies over the long centuries and societies in this very moment have not made living the kindest of experiences for women—societies governed and purposed by my people, by men. I hate us for these inequities and a book like Sakuran fills me with tidal waves of regret and sadness, even if that is not its purpose.

Moyoco Anno’s Sakuran concerns Kiyoha, an 18th-century courtesan who is destined (by Anno’s pen) to become the most celebrated of all the houses in Yoshiwara. Anno begins by introducing Kiyoha as she nears the height of her fame and then peels back for the rest of the book to chart the woman’s course across what turns out to be a hard and bitter sea. Kiyoha is a “strong” female character in the sense that she survives to better herself through her experiences; but simultaneously, she is not immune to her circumstances and her life of prostitution under contract to her house takes evident toll on her. She realizes the world she’s trapped by is terrible and makes the best of it, but she never shies away from acknowledging the reality that her role as courtesan is dominated by paternal influences.

I have it on pretty good authority that “sakuran” refers to confusion or derangement or mental agitation. The book’s subtitle Blossoms Wild, as well as an apt description of the madness of Kiyoha’s blooming sexuality under such a terrifying commodification of the female self, seems pretty probably a play on the homophony between sakuran and sakura, the Japanese term for cherry blossoms (and one of the more well-known Japanese words in America, thanks to the influx of manga and anime imports). Kiyoha’s maturing and sexual bloom within the walls of the pleasure house is agitating for the character as well as for the reader. It seems trite to compare our distress to hers, but it’s Anno’s implication of the reader into the intimacies of Kiyoha’s decade of depetaling (I recognize the preciousness of describing a woman’s initiation into coupled sexual experiences as “deflowering,” but Anno almost pushes the description by her title—as well, the coercive nature of Kiyoha’s sexual engagements are rapacious and demanding and strip her of any of the tenderness we treasure in the potential warmth of the sexual act) that provokes the reader to empathize with Kiyoha’s state—even if to a lesser degree.

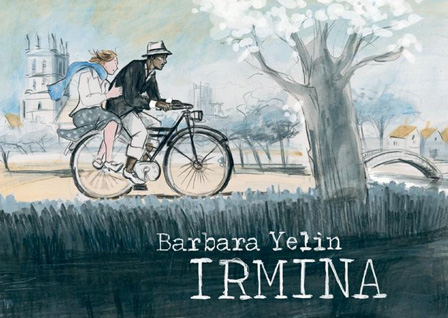

Irmina

by Barbara Yelin

228 pages

ISBN: 1910593109 (Amazon)

Genre notes: war at home, romance

The fact of Nazi Germany haunts the 20th century (and even still the 21st century) like a particularly strident and pernicious spectre. How? How! How on earth could Nazi Germany have been allowed, been encouraged?

A few years back Barbara Yelin discovered a box of her grandmother's letters and diaries. From that box grew the story of Irmina, a young woman who in 1934 was living abroad in London, gaining skills and forging a path for a future in which she could grab anything she wanted for herself as well as any man could. She is of course young and with youth comes naivete, willfulness, self-righteousness, and a colossal kind of self-centered ignorance. Still, how could that young woman of raucous attitude and vivacious heart be tens years later passively complicit in the Nazi machine, buying into (to some degree at least) the promise of volksgemeinschaft?

How could a young German post-suffragette proto-feminist go from being fiercely, desperately in love with a black man from Barbados and openly mocking Herr Hitler in the streets to working in the Reichskriegsministerium and chiding non-gung-ho friends with threats of reporting (I show some of this evolution in the accompanying pictures). From 1934 and though 1945 and then to 1983, Irmina paints a portrait, not just of a particular woman through the global scene of the 20th century, but really of how these vast shifts of paradigm are acquiesced to and adopted by the "ordinary" citizen.

How the World Was: A California Childhood

by Emmanuel Guibert, Kathryn M. Pulver (translated by)

160 pages

First Second

ISBN: 1596436646 (Amazon)

I am not old but I’m not young either. I was born in the early ’70s and so was part of perhaps the last bulk of free-range children. We roamed neighbourhoods in packs or on our lonesome. We hiked in the local wildernesses on our own or perhaps with a friend, rattlesnake buzzing be damned. Our parents routinely left us in the car to play while doing a half-hour of grocery shopping and no one was at all concerned. The smog in Los Angeles was so thick and constant that skies were perpetually orange and it often hurt a child’s lungs to play and on bad days you couldn’t see further than a hundred yards. Payphones were essential lifelines. Dialing a phone number containing nines and zeroes might have taken eternities. Not every middle class family owned a computer. People were afraid the D&D players were sacrificing each other in bloody masses in underground tunnels. And the difference between my childhood and my father’s immediately-post-WWII childhood is as vast as different between now and 1980. Worlds tilt and shift and change, and if we don’t tell these stories, no one will remember to care.

For this reason, Emanuel Guibert’s treatments of Alan Cope’s life are essential and fascinating. How the World Was follows on the heels of Alan’s War, which largely concerned itself with Cope’s place in WWII and its aftermath. How the World Was winds back the clock (another thing growing less and less common) to explore Cope’s childhood growing up in Southern California during the Depression. And it’s a world-and-a-half away from the Southern California I grew up in.

Guibert recreates a number of Southern Californian environments now lost to time save but for the archival efforts of photograph collections and artistic renderings. They portray another kind of world and will be fascinating to students of human history and nature. Scenes from the early 20th century abound. Soda shops, old-town L.A. County, the boardwalk at Santa Monica, simple Depression-era housing. Leave it to a French work to inculcate a nostalgia for a thoroughly American world now lost to us for all time.

Bad Machinery

by John Allison

7 vols

Oni Press

ISBN: 1620100843 (Amazon)

When I was a budding teen, I was probably just about what you were like. I was whip-smart, sardonic, and had no problems elucidating my every bursting thought with exactitude. I was, for lack of better description, charming. I wouldn’t go quite so far as to say “debonaire,” but really that’s probably just modesty speaking. I dressed well, spoke well, and forged relationships well. With either sex. Didn’t matter. I was basically the stuff. Except for the fact that none of that happened. I was instead probably just about what you were like. I was, for all my smarts, a bit of a moron. Couldn’t properly express myself. Flummoxed and self-concerned around both boys and girls, but unconquerably so around girls. And then throw on top of that the fact that I was, as J.M. Barrie describes children, innocent and heartless.

Again, I was probably quite a bit like you. Not because you were a particularly horrible person but simply because budding teens are not very good at being the people they have the potential to be. Junior high is a terribly awkward stage. Our bodies are wrong, being trapped in the uncanny valley betwixt the hopefully adorable child-self and the hopefully awesome adult-self. Limbs jut out here and there in clumsy efforts to rush toward that which we yet aren’t. Breasts leap from the canvas of our bodies. Unwished for erections make tents of our jeans. Strange thatches and patches of hair appear at first as if mirages. New smells collect around us. The blood times, the nighttime ejaculations, the hormonal spasmatics. It’s a tough time to be a person. And all these physical oddities combine with the other demands and expectations of growing older to temporarily hobble the psychological state of the young. Stew all this together and you’ll find that people in the age range of twelve-to-fifteen are some of the most difficult, squirrely, and (sometimes) unlikeable people you know.

And it’s not like its their fault. It’s understandable. It happens to all of us. I just maybe don’t want to read about such people. So the more realistically a book portrays its young teen protagonists, the more I find myself distanced from any ability to enjoy the work. Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix was nearly unreadable to me. Harry was so thoroughly unlikeable and whiny and stubborn and blind and conceited because Rowling did a fair job at approximating what a good kid in Harry’s position would be like. I hated nearly every minute with him. It got to the point that I wanted him to lose just so it’d knock some sense into him. I mean, congrats to Rowling on writing a believable fifteen-year-old, but I almost left the book unfinished because of her triumph. So then, I’m glad for what John Allison does in Bad Machinery, a book thoroughly concerned with the lives of budding teens.

I’m not even quite sure of the alchemy by which he does it either. Most authors, having recognized that realistic teens are neither enjoyable teens nor entertaining teens, ditch the idea of realism and simply write their characters as adults in kid bodies and then strip out the more, quote-unquote, adult habits (drinking, swearing, sexing, stock-trading) from their characters. This leaves their young protagonists free to operate in generally reasonable demeanor and not flip the heck out over what adults might consider trivialities. It’s okay so far as it goes, but always ends up feeling a bit hollow. Allison, somehow, finds a warm place in between whereby his characters can carry on conversations like ridiculous, amusing, meta-witty young adults while simultaneously skirting into realistic interaction with their world.

Bad Machinery is one of those strange Modern Hybrids that we’ve seen rise up with the advent of the web and its associated comics. The series unfolds in the macro sense over a series of mysteries. These arcs resolve themselves under the taxonomy of cases. The first is “The Case of the Team Spirit,” which is followed by “The Case of the Good Boy.” There are currently eleven (I think?). Within each case however, each page is revealed a day at a time to the reader—and in common webcomic fashion, these each usually resolve in something like a punchline. The story unfolds across these brief punctuations with time and place often shifting dramatically from one page to another. Still, it all keeps together well, and it may be that the promise of a joke or witticism or revelation at the end of each page actually works to spur the reader onward. After all: it’s easy to bookmark a page and let go for the night if you know you’ve got another thirty pages ’til the next breaking point. Not so easy to let go when there’s a breaking point every page—not enough pressure to stop when it’s only a thirty-second read to get to the next rest area.

Allison’s series is the tale of boy detectives. And girl detectives. Youthful detectives, at any rate. Of either sex. They work, sometimes together and sometimes at odds, to solve various mysteries. It's basically like Scooby Doo except whereas in Scooby Doo every unearthly mystery had a very mundane cause, here every mystery begins easy enough but soon plays court to the supernatural. The reason I may not have noticed this is that even though there’s plot for each of these arcs and you really do want to know how things are going to piece together, the real reason you’re devouring these stories is Allison’s magnificent characters. The kids, who alternate in good measure between realism and wonderful fantasy, are deliciously wrought. Their interaction and distinct personalities mesh so well together that I worry for them as they age, knowing that they’ll eventually all move in their own directions—and we actually see some of this unfold across the years represented in these cases. They start out the series at the ripe old age of 12 years old and in the current case, I believe they are straddling the land of 17 years old or something around there.

Also, these are some of the funniest comics around. I forget if I mentioned that.

Ultimate Spider-Man

by Brian Michael Bendis and Mark Bagley

22 vols

Marvel

ISBN: 0785124926 (Amazon)

Okay, so Marvel and DC hero comics are a trash heap, right? RIGHT?! (Stay with me even if you disagree and think I'm a bum now.) So why recommend one? Because every so often, even if pretty rarely, they overcome the inertia of their marketing paradigm and make something pretty worthwhile. Ultimate Spider-Man overcomes those forces for as long as it can and is often pretty great. Until Marvel ultimately pooped on the whole thing. But until then, it was solid.

So I've talked about Marvel/DC hero books as not being about characters at all but instead about storytelling engines before. Essentially it goes like this: these books don’t actually feature Character in any honest sense of the term. Instead, they feature storytelling engines. Or maybe better, storytelling prompts. A reader of Spider-Man in 1970 can more or less jump into Spider-Man in 2010 and pretty much know exactly what’s going on. Only the trivialities (like who is punching Spider-Man now) have changed. Same with Superman, Batman, Captain America.

Spider-Man is merely a series of tacitly connected short stories set in the same world and using the same set of character-props. Where characters have arcs and growth and progression, the whole point of Spider-Man or Batman is to tell Spider-Man or Batman stories. They can never be allowed to stray from archetype because they are not characters, but product generators. That’s why I couldn’t stay invested. There was nothing to invest in. There’re only so many times that you can read the biographies of Abraham Lincoln before you—for your own sanity probably—have to move on to other biographies, to other persons.

That's one of the two reasons I stopped buying superhero books back in 2006. The other reason were the crossover events. They infected everything. They stomped all over whatever stories were being told. It's stupidly hilarious to get an omnibus collection of stories from any point after 2005. I'd heard good things about Brubaker's Captain America, so I picked up the omnibus and it was really pretty great and then suddenly all these crazy abrupt things and character changes were happening. It made no sense at all *until* I realized that there was some crossover event or other creeping in and changing everything. It'd probably make sense if you were following both things concurrently, but otherwise, it's really weird.

Anyway, because Ultimate Spider-Man takes place in its own little world, it takes a good while for these two problems to take hold. Add to that the fact that Ultimate Spider-Man is pretty nearly the platonic form of Spider-Man and you've got a nice, enjoyable adventure soap.

USM begins with Peter getting bit, there's the Green Goblin and Doc Ock and Kingpin and everyone, but they're all rewritten from the ground up. There is no prior continuity and it's great. Really early on, Peter tells his new girlfriend Mary Jane that he's Spider-Man. Gwen Stacy comes along eventually. Venom. Wolverine. Black Cat, Daredevil, Flash, Kitty Pryde, etc. The usual cast and crew. Only they're all new and all different. Eventually, the book does start to feel some bloat, but Bendis is so very dogged on focusing on this as Peter's book (rather than Spider-Man's) that his small group of regular teenage friends anchor everything and keep it from wallowing in tights and excess.

And Bendis, amazingly, writes Peter and this book pretty much better than nearly anything he's ever done. All of his Bendis-y tics and tropes just really work well with this version of Spider-Man.

Eventually, Marvel marketing *does* catch up to the book, first to ruin everything with a big Ultimate-Universe crossover that is terrible and stupid BUT does create one of the most poignant issues in Marvel history, when J Jonah Jameson realizes, startled, that he has been 100% wrong about Spider-Man and becomes his biggest booster. Then, in the strangely on the nose arc "The Death Of Spider-Man," Marvel kills Peter in another big event. This isn't really a spoiler because the book is actually called The Death Of Spider-Man. Amazingly enough, Bendis keeps the ball alive by introducing Miles Morales, a black Latino kid who becomes the new Spider-Man and his story is possibly even better than Peter's. This continues for five volumes before Marvel irrevocably destroys the whole thing for all time in a line-wide event that actually destroys the Ultimate Universe. Miles' Spider-Man is brought into the regular Marvel universe, at which point you never need to read again because his whole cast is gone or changed and he's screwed tightly back into the whole reason I got out of their comics.

But man, while the series is good, it is so good. Just simple fun adventure.

Jane, the Fox, and Me

by Fanny Britt and Isabelle Arsenault (translated by Christelle Morelli and Susan Ouriou)

104 pages

Groundwood Books

ISBN: 1554983606 (Amazon)

This was a surprisingly lovely story, if only because lovely things always catch me off-guard. It's about a girl who is concerned about her weight and feels the brunt of social antagonism at her school (even though just a year prior she was friends with all the popular girls). She also likes reading and over the course of the story moves through the text of Jane Eyre. It's sweet without succumbing to that overly treacle sentimentalism that costs too many books their laurels. And it's beautifully illustrated.

Cape Horn

by Christian Perrissin and Enea Riboldi (coloured by Studio KMzero, Diego D'Aquila and Sebastien Lamirand, and Hélène Lenoble and translated by Quinn and Katia Donoghue)

232 pages

Humanoids

ISBN: 1594651302 (Amazon)

Cape Horn tells a story of 1890s Tierra Del Fuego, a place steeped in colonial interest. From soldiers to mercenaries to missionaries to vagabonds to the native Yámana people, Cape Horn (the book) is filled with different people with different goals and different identities. Few come to find happiness, but adventure rules the day.

Cape Horn is thrilling and gorgeous and occasionally even thoughtful. This was my #5 Best Graphic Novel of 2014.

And as an added bonus, every time I say the title, my wife hears K-porn (like how Korean pop music is called K-pop). So that's always good for a giggle.

The Eternaut

by Hector German Oesterheld and Francisco Solano Lopez (translated by Erica Mena)

372 pages

Fantagraphics

ISBN: 1606998501 (Amazon)

The Eternaut surprised me. I know it probably shouldn't have. Everyone was telling me to read it. But still.

There's this thing about a lot of older works that are well-venerated. Despite all their dignity associated with the place they hold in comics history, despite all the ways they influenced what we see in the field today, and despite all the ways they were actually really really good for their time—despite all these very important and legitimate things, many of the great works of the canon feel hackneyed and primitive when stood next to our contemporary greats. And no shade there, really. We should expect this. We should expect that when giants stand on the shoulders of giants they should loom much larger.

So when another wonder from a half century ago gets repackaged handsomely for a contemporary audience, I'm reluctant. I've been burned too many times, thinking I might find jewels relevant to my reading interests today. I imagine that somehow some long dead author might have anticipated the cultural condition I find myself in and have written to my particular milieu. And while that's at least plausible when we're talking about novels (after all thousands and thousands have been published every year for centuries), far fewer comics have been published and so the chance of genius spilling across time becomes slim.

The Eternaut, though. Man this feels fresh. Apart from some idiosyncracies native to the format limitations (one page per week in a newspaper), the book reads well. It's a longform, succinct story of the Twilight Zone variety that stands well apart from its contemporaries that I've encountered. This is sustained narrative while simultaneously having an end point, unlike the unending adventure-story engines of its North American contemporaries. Additionally, it offers some similar kind of political/historical commentary in the manner that Sonny Liew offers in The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye. I rarely feel I'm beholding something special when I read vintage comics, but I felt that with The Eternaut.

Solanin

by Inio Asano (translated by JN Productions, Annaliese Christman)

432 pages

Viz

ISBN: 1421523213 (Amazon)

I first read Solanin almost a decade ago. And I only read it the once. I thought it was a good book, well-conceived and well-produced, but it didn't hit me as one of those books I needed to return to over and over again. It was no Cross Game after all. But needing a good book to recommend here, I thought I'd return to it and see how it struck me all these years later. And, well, it's pretty great.

I've been a fan of Asano since Christmas 2009 when I first got Solanin and What A Wonderful World. I liked Solanin fine, but What A Wonderful World was the one that grabbed me by the lapels—and I didn't even have lapels. I've followed his releases since then and his voice and vision have proven unique and worth consideration. And he continues to rock worlds.

Solanin is about a boy and a girl. 24-year-olds in Tokyo, trying to figure out life. Only not trying too hard to figure out life. Meiko works an office job she hates and Taneda does freelance illustration (bad hours, bad pay). They live together but their future is uncertain. Taneda plays guitar and dreams of his band making a difference, but his pride and self-consciousness prevent him from exerting himself or treating the dream seriously. Their friends occupy similar holding patterns and are governed by the fears and uncertainties native to the human condition.

Will the power of music save their lives or destroy them? Or is there really any power to it at all and does any of it truly matter when on this very day there is a war going on and normal everyday people are dying senselessly? Fans of Ecclesiastes may enjoy this one as questions about the vanity of all things echo its halls. Gorgeous art with some stellar, powerful moments.

And now, with an epilogue volume catching up to characters a decade later, Solanin becomes even richer.

Order of Tales

by Evan Dahm

720 pages

Self-published

Read here

Order Of Tales occurs in the same world as Rice Boy and Vattu, only much before Rice Boy and much after Vattu. In the millennia since Vattu, there is little to resemble the Overside world unveiled in the latter work (Vattu), but there is some carry over from (or into) Dahm's earliest work, Rice Boy. T-O-E, the One Electric appears in both. In Rice Boy he is at the end of his journey, but in Order Of Tales, he is hundreds of years younger and perhaps marginally more idealistic.

Dahm's worlds are rich and complicated and beautifully wrought. Where Rice Boy capitalized on the wild and imaginative, and Vattu emphasized the grand and political through the venue of the personal, Order Of Tales plays heavily on the adventure, the hero, and the nature of the story.

I don't know if Order Of Tales is my favourite of Dahm's works. It might be. It always is right after I read it, but as a creator he's so deliriously talented that a dive into any of his works are well worth the time spent.

It's pretty rare the webcomic that I'll take the time/money to get in physical form, but Order Of Tales is one of those. It's big and hefty and filled with wonders.

101–110111–120121–130131–140141–150

151–160161–170171–180181–190191–200

A Taste of Chlorine

by Bastien Vivès (translated by Polly McLean)

144 pages

Jonathan Cape

ISBN: 0224090968 (Amazon)

A Taste of Chlorine is an evocative treatment of language, of the wonders and woes of the human spirit’s attempt to connect to others of the like. Bastien Vivès seems focused on the elusivity of that connection and the concern that even physical proximity can be alienating if language falters. In Taste of Chlorine, art and design and story conspire to sing a kind of methodical lament, a series of mechanical refrains meant to mirror the repetitive nature of the act of swimming while simultaneously signaling an anthem to the soul who struggles with human connection.

Vivès strikes at how simply we might be distracted from accessing the true meaning of words. A Taste of Chlorine incisively intimates how easy it is for two people to remain foreign to each other—to be shuffled from the path of understanding and hope by little more than a misplaced word and an absence of meaning. This is the story Vivès toys with and his art throughout drives this home.

For a work concerned foremost with communication, Vivès spends surprisingly little time on actual dialogue. He lets his art speak for him and for his characters. The story moves through the stealing of glances, the submergence of physiques, and what is revealed above and below the waterline.

GoGo Monster

by Taiyo Matsumoto (translated by Camellia Nieh, lettered by Susan Daigle-Leach)

464 pages

Viz

ISBN: 1421532093 (Amazon)

Gogo Monsters straddles some sort of line between absurdist, surrealist, and fantasy. It can be difficult to follow because the reader will often be uncertain whether the experiences depicted should be considered reality, imagination, or metaphor. There are textual cues that led me to vote for Reality, but you never know.

Matsumoto’s story, in its most overt, surface reading plays out over the course of a year and follows the story of a school that is increasingly beset by misfortune and misbehaviour. More properly, the plot may be said to concern three children in varying stages of social pariah-dom. Makoto, a third grader, is the most even-keeled of the three and spends most of his time alternating between interest in and alienation from his bizarre classmate Yuki. Yuki sees visions of another world, one that overlaps with our own, and he attributes much of the gathering social darkness to the activity of the other-worldly “others”—though the flame of his faith is being somewhat diminished by recent conversations with IQ. IQ, a mathematical genius, is a fifth grader who wears a cardboard box over his head at all times and sees Yuki’s beliefs about the other world as mere psychological extrapolations of his intense feelings of loneliness. IQ and Yuki are explicitly shunned by their classmates, while Makoto hangs on to some degree of social relevance despite concerns about his curiosity toward and friendship with Yuki. As these characters wend their way toward their individual fates, Gogo Monster may or may not (depending on one’s interpretation of events) reveal whether Yuki’s imagination has gotten away from him or not.

It’s a curious book and each reader’s interpretation will lead into a variety of questions about authorial intent and whether Matsumoto merely intended to tell the kind of trippy story that high-school–aged writers love to think is amazing and mind-blowing—or whether the author has bigger fish to fry. Matsumoto lays a lot of groundwork for a robust interpretative challenge and Gogo Monster is a thought-provoking work—and that alone is enough to recommend it.

Doomboy

by Tony Sandoval

136 pages

Magnetic

ISBN: 0991332474 (Amazon)

Id has lost his love. She's gone and all he has left is metal. And one friend, maybe two. And a radio to broadcast on. He finds a spot on the coast and tries to express through one final cataclysmic metal masterpiece the depth of his heart. What he believes to be a performance to the void alone turns into something much more.

Doomboy has a pretty good story that is easy to forget in the face of Sandoval's magnificent illustrations. The art plays such a strong role that it often even threatens to subsume everything else in the book. Which is almost the perfect way for this crazy book to roll out.

Planetes

by Makoto Yukimura (translated by Yuki Johnson, lettered by Susan Daigle-Leach)

2 vols

Dark Horse

ISBN: 1616559217 (Amazon)

Before Vinland Saga, Makoto Yukimura had this story about space garbage collectors (or more particularly, debris collectors). Also more particularly, it wasn't so much a story as a set of stories. Each explred one more aspect of his cast and their dreams, their nightmares, their motivations, their circumstances, and the question of meaning that lurks behind every life. Planetes is as good a reason as any to give to justify the existence of comics. It's thoroughly worthwhile.

The Theory of the Grain of Sand

by Benoit Peeters and Francois Schuiten (translated by Ivanka Hahnenberger and Stephen D. Smith)

128 pages

IDW

ISBN: 163140489X (Amazon)

Les Cites Obscure is Schuiten and Peeters' realm of fantastic cities and strange events. They exist in a world parallel to our own and many of the cities reflect our own world to degrees (for instance, the Palace Of Three Powers in Brüsel is a near replica to the Brussels Courthouse in, well, Brussels. Les Cites Obscure currently features in thirteen vols in France.

The Theory Of The Grain Of Sand is the second vol to be produced in the US. (I had wanted today to cover The Leaning Girl, which is great, but it's now out of print and used copies go for $125.)

In both US vols of The Obscure Cities, Schuiten and Peeters play on a combination of the overt and unexpected. In the narrative of TTOTGOS concerns the appearance of some weird things: the multiplication of rocks of the exact same weight, a chef who is gradually losing weight but not mass, an apartment that produces sand, and more. But using the visual magic of comics, we find that these things are all related—because as one single character (and no other) can see, these things all shine and shimmer.

It's an exemplary exploration of the imagination and while I prefer The Leaning Girl, TTOTGOS is a strong work that boasts more of Schuiten's incredible linework.

Louis Riel: A Comic-Strip Biography

by Chester Brown

280 pages

Drawn and Quarterly

ISBN: 1894937899 (Amazon)

Biographers, it happens, are every bit as much storytellers as Dickens or Gaiman or Hemmingway or Stoppard. They not only have a responsibility to the historical record, but perhaps more importantly, they are beholden to the attentions of their readers. The occupation of a straight fictionalist almost must be easier—for the simple novelist may take a story in any direction and pace it in a manner that will drive readers to continue until story’s end. The biographer, on the other hand, is more like a film editor who has to craft a compelling story with found material he had no hand in creating. So it’s understandable that biographers might take some license with the truth.

As if truth and history even belong in the same sentence.

Chester Brown, as he unfurls the history of Manitoba’s founding rascal-hero, carefully chooses which directions to have Riel’s story take and which paths the man should tread. Often in his research Brown is confronted with conflicting reports, some from recollections published well and many years after any of the involved incidents. As interesting as Riel’s decisions and circumstances are, it may be still more fascinating to chart Brown’s own choices as to which of these to portray—and how.

Brown is forthright about his biographer’s role in the fabrication of Riel’s historical record—and really, that just makes the work that much more intriguing. Knowing that the author is not bound overly by, quote-unquote, historical fact draws more attention to Brown’s skill as a storyteller. He is unshackled enough that he can tell the story he is going to tell in the way he wishes to tell it. And while there is certainly some subjectivity at work, I can say that at least from my reader’s perch, Louis Riel is an unqualified success.

With its abrupt and overly simplified style, Louis Riel is able to present Riel’s story in a way impossible for a prose novel. Visual space is used to create story beats, punctuating decisions or underscoring the humour in a given situation. Entire conversations, discussions, and arguments occur over two or three panels, with dialogue as spare as Brown’s art. The pacing and storytelling is excellent throughout. Brown attributes the drawing style he employs across the book to his love for Harold Gray’s Little Orphan Annie. Hollow, pupil-less eyes float detached in wide-open faces. Brown’s rendering of these historical figures is iconic and indelible.

Dream of the Rarebit Fiend

by Winsor McCay

714 pages

CreateSpace

ISBN: 1479106569 (Amazon)

Winsor McCay is largely known for his bizarre and imaginative and colourful Little Nemo comics, which ran in Sunday papers from 1905 to 1926. During nearly the same period (1904-1925) McCay drew a similar strip called Dream Of The Rarebit Fiend, often under the name Silas (for contractual reasons).

Dream Of The Rarebit Fiend follows a similar structure with Little Nemo in that the dreamer becomes increasingly aware of the chaos of their dream and wakes in the final panel (usually remarking on how they should not be eating Welsh Rarebit before bed). But while structurally similar, DOTRF is much more adult oriented, dealing with mature themes like suicide, insanity, social situations, alcohol. Each strip is self-contained and there aren't really recurring characters.

DOTRF, like Nemo, has been published in numerous editions over the years. A few years back Ulrich Merkl released a large (12x17") hardcover edition with a lot of background and history and essays to give context for the series. It sells for stupid amounts on Amazon currently, but if you ever run across a copy for less than $200, it's worth it.

Dover has an 80-page paperback selection of the strips for 12 dollars. The pages are 8.5x11"

CreateSpace has a 714-page edition for 20 bucks. The dimensions are a bit smaller at 7x10" - but the quality of the book is apparently pretty weak with many of the strips too small to read.

Buddha

by Osamu Tezuka (translated by Yuji Oniki and Maya Rosewood)

8 vols

Vertical

ISBN: 193223456X (Amazon)

In Buddha, Tezuka presents a curious blend of themes and styles. This project, ten years in production (1974–1984), presents the life of Siddartha Gautama, the Buddha, from birth to death, capitalizing on famous episodes and creating fictional ones as well. Tezuka includes a robust cast of characters both fictional and historical that waxes and wanes over the near-century that the story narrates.

Not being a Buddhist, I have no idea how well Tezuka’s tale reflects either the historical man or the religious conception of him (though genuine Buddhists do seem to like the book). And I don’t know if Tezuka was Buddhist or not, though it seems likely or plausible. One thing, however, is certain: that Buddhists enjoy the book speaks well of their sense of humour with regard to their faith’s central figure. I cannot see a similar book being crafted about the life of Christ being well-received. And a similar version of the life of Mohammed would end in bombs, death threats, and ambassadors demanding apologies.

Because the thing is: Tezuka’s tale is as irreverent as it is reverent.

He clearly thinks highly of Buddha and his teachings. And yet, the books is filled with jokes and antics and all kinds of nuttiness. Pokes and jabs at Buddha himself are rare (though present), but there is a constant stream of silly asides, even in the midst of what would otherwise be a sober scene fraught with drama. A horse will arrive astride a messenger to deliver dire news to the king. A character will be confronted by his haunted conscience, seeing a vision of Buddha speaking to him—only, since it was a vision, he wakes to discover he’s been talking to his horse all along. Characters from Tezuka’s other works show up not infrequently and even Tezuka himself appears in cameos, taking the place of a character for a single panel.

The story is filled with anachronisms as well. Both visual and verbal. At one point, a poor peasant family wishes to send their son with Siddartha as he follows the path of monkhood, claiming that their son should be able to become a monk “in this day when even actors can become president.” There are further references to Paris and New York and Spielberg. E.T. and Yoda even make appearances, and at one point a royal councilor asks if Buddha actually is E.T. (as Buddha has just healed someone with the touch of a finger).

It took me a while to get a handle on exactly how to approach the book. The fact of the sheer silliness of moments. The fact of the gorgeous and highly detailed landscapes intruded upon by Disney-esque cartoon characters. The fact of main characters who die 300 pages in to the 3000-page epic. The fact that every woman in the book is topless. The fact of mixing faith and fantasy so seamlessly in a book that I believe is trying to promote the teachings of Buddha. And the fact that Buddha isn’t even born until the end of the first volume. It was a weird mix, but after not too long, I found myself quite at home with his unique style and let the story wash over me.

Vattu

by Evan Dahm

3+ vols

Self-published

Read here

While Rice Boy was fascinating and inventive and Order of Tales offered a superb yarn, Evan Dahm's Vattu is his most ambitious story yet—a multithreaded, complex narrative about the crossing of cultures, imperialism on the verge of post-imperialism, the semitotics of identity, and how language shapes us.

While Rice Boy's colours were flat and Order Of Tales was black and white, Vattu is vibrantly coloured with a perfection of details. It's a beautiful book. I'm hungry to see the story complete if only because I 1) love the satisfation of a story concluded and 2) can't wait to see more stories in Dahm's world.

Nathan Hale's Hazardous Tales

by Nathan Hale

8 vols

Amulet

ISBN: 1419731483 (Amazon)

Nathan Hale's Hazardous Tales are amazing. Basically, its a series telling stories from US history geared for young readers. Only, I have kids and I bought the entire set of available books not for them but for me. Because they're such a deep pleasure.

Book 1 is about Nathan Hale, the Colonial spy during the American Revolution whose last words before being hung were "I regret that I have but one life to give for my country."

This sets up the series. While Hale is on the gallows, the Big Book Of History swoops down, swallows him and then spits him out (as is its wont). He now has Complete Knowledge of the full breadth of American history. So he delays his execution by telling stories from US history to the hangman and the British officer attending his execution. It's pretty hilarious and the characters interrupt the stories Frequently to offer asides and whatnot.

- Book 2 is about the Ironclads in the Civil War

- Book 3 is about the Donner Party (for kids!)

- Book 4 is about WWI and is so disturbing that Hale (the author not the spy) gives all the actors animal heads to make it a little Holy Hell.

- Book 5 is Harriet Tubman

- Book 6 is The Alamo

- Book 7 is the Doolittle Raid and WWII

- Book 8 returns to the American Revolution and Lafayette

The way Hale (the author, not the spy) weaves these tales using the fourth-wall obliterating Spy Hale, hangman, and officer as foils is so soooo entertaining. These are stories about heroic deeds and grim doings, but they're told effervescently. Humour, excitement, and education all rolled into one.

One of my favourite parts is this great bit from the Donner Party one, in which the hangman, who up to this point has been so disturbed by the deaths of the travelers' animals (despite being a regular killer of humans himself), decides he can't take it any longer and so he flips forward to nearly the end of the book to skip all the terrible deaths of pets that he imagines will mark the tragedy of the Donner expedition.

Seriously though. These books are so interesting and so educational that I can't believe it took me this long to get to them. In 5 pages, the Alamo one lays out the whole background to the Alamo event better than anything I've ever encountered. The WWI one gave such a great overview of the War that it is now the book I'll recommend to anyone who wants an overview of the that whole trouble.

101–110111–120121–130131–140141–150

151–160161–170171–180181–190191–200

Beautiful Darkness

by Fabien Vehlmann, Kerascoët (translated by Helge Dascher)

96 pages

Drawn and Quarterly

ISBN: 1770461299 (Amazon)

On the surface, it seems pretty straightforward. A young girl dies in the forest and a host of tiny, often grotesque people emerge from her corpse and struggle to survive in the woods. But it really isn’t that simple. There is more there, sometimes under the surface and sometimes squirming on top. I found the publisher’s descriptive text unhelpful and probably actually wrongheaded.

"Kerascoët’s and Fabien Vehlmann’s unsettling and gorgeous anti-fairy tale is a searing condemnation of our vast capacity for evil writ tiny. Join princess Aurora and her friends as they journey to civilization’s heart of darkness in a bleak allegory about surviving the human experience. The sweet faces and bright leaves of Kerascoët’s delicate watercolors serve to highlight the evil that dwells beneath Vehlmann’s story as pettiness, greed, and jealousy take over. Beautiful Darkness is a harrowing look behind the routine politeness and meaningless kindness of civilized society."

None of this reads like someone who actually grokked the work. At least not closely. I may not understand Beautiful Darkness completely, but I do understand that the above reading is incompatible with the text as revealed. Aurora is not a princess. The idea that this is an allegory for human survival against the instinct for societal self-immolation fails to fit the available information. Other reviews invoke Lord of the Flies (which is fine, I guess) but leave it there with William Golding’s critique of the natural human spirit as being essentially depraved (which is not fine, and actually lessens Beautiful Darkness as a mere derivation of a common observation).

I don’t wish to be too contrarian because it’s likely that these readers didn’t understand the book any better than I did. Making too much of something, going for the facile interpretation—it’s an easy trap to fall into when one feels as though they have to say something wise, intelligent, or insightful about a book. I feel that pressure a lot. And I’ve fudged things before as well. So it’s not like I’m blameless. I think I just wished for better criticism because I love this book and want to understand it.

I love this book for what it appears to be. I love this book for the promise of what it might be. I love this book in the same way a sixth-grader might have a world-shattering crush on the girl two rows back in World Cultures. She is seen and heard but ultimately only known tangentially. But still, she is a fixation—and adored. That is Beautiful Darkness to me. It’s lovely and amazing and probably the most perfect thing ever created. Just like that girl in sixth grade you never spoke to and whose real identity remains a mystery to this day. Unattainable and foreign: the perfect crush.

Red Handed: The Fine Art of Strange Crimes

by Matt Kindt

272 pages

First Second

ISBN: 159643662X (Amazon)

While very different from Super Spy structurally, Red Handed does something similar in terms of taking several disparate threads and weaving them together into a satisfying whole. The stories of strange criminals start and stop, each concluding with the perpetrator being cuffed by the city’s super detective, Gould. These are interleaved with artless sections of dialogue. It takes a while to apprehend the pattern—but when one does, it’s hard not to stop and think “Heh” or “Little scamp” or “Whoa” in that kind of way that offers a silent congratulations to Kindt for letting us take part in this twisting genius.

Beyond the conceit of the Twist—that moment in the storytelling when the author turns the tables on the reader and turns the story they were reading into another story entirely—Kindt’s structure for Red Handed allows him to effortlessly break off from his story and engage in a little bit of philosophical discussion about the nature of crime and law. Often in ambitious literary work, these excursions are narrative cheats that authors use to force-feed some added value into what would otherwise be a pretty mundane set of plot paces. While I was nervous for a time that Kindt had stepped into that common trap, Red Handed vindicates itself and Kindt uses these discussions to inform the story and enrich the reader’s participation in its conclusion. In fact, Kindt’s finale would be hollow without the ranging conversation that governs it.

Sailor Twain: Or: The Mermaid in the Hudson

by Mark Siegel

400 pages

First Second

ISBN: 1596439262 (Amazon)

For centuries, mermaids were known as creatures of havoc—happy to destroy the lives of sailors. Long linked to the sirens of Greek myth, the sociological purpose of their legend seemed to have been pedagogical, speaking to the danger of the seductress. Mermaids would use their allurements (both in voice and body) to draw sailors to a death of submergement. They represent the futility of the male passion in that their upper torsos (what would be visible above the waves) picture the truest and most desirable physical beauty, while the body existing below the waist offers no culmination to the male romantic expression. Doomed loves, doomed lives. And refreshingly, it is this kind of mermaid lore that Mark Siegel explores in Sailor Twain.

Sailor Twain is a triumph of collaboration. Lore, history, mood, social ethics, and romance swirl together, weaving a thing of ominous beauty. The mermaids’ contemporary myth is subverted in the book’s reclamation of the antique myth. In telling the tale of Captain Elijah Twain, Siegel skates through and about a world pitting loyalty against lust, where temptation holds court and the verdict is yet to be decided. This is a story about sex, about desire, and about how dangerous these things can be when directed without discretion. In a way, the book offers a moral as quaint as the lore with which it concerns itself—though even this moral is twisted in deliciously challenging ways as happily-ever-after careens drunkenly from comfortable expectation. Siegel raises delicious questions to challenge our presuppositions through a story illustrated and written with obvious care.

Siegel’s narrative concerns Elijah Twain, charged with the captaincy of the Hudson river steamboat Lorelei. It’s 1887 and Twain (no relation to the author, who wasn’t really named that anyway) is a man of strict personal governance, bound by his morals, his promises, and his watch. One evening, he discovers crawling onto his deck a wounded mermaid, a victim of a harpoon. Her name means South and he cares for her injuries; things both ravel and unravel from the beginning of his stewardship of her.

I Kill Giants

by Joe Kelly and J.M. Ken Niimura

7 vols

Image

ISBN: 1607060922 (Amazon)

I Kill Giants exploits expectations in order to tell a story that, while common, is made special by its telling. The creative team breathes a crispness into Barbara Thorson’s imaginative life that many such tales lack—and those stories, in their lack, are built of shallow caricatures that never come to life for the reader. Traveling with Barbara through the travails of her fifth grader’s existence, we are given a unique vantage into the lives and motivations of much of her supporting cast. There are still clichés that never entirely extricate themselves from the crushing weight of their familiarity (for instance the story’s bully, Taylor, is just like every other storybook bully you’ve ever encountered in bad literature), but for the most part Kelly’s script is a relief.

Accordingly, Niimura’s visual work impresses when one considers just how easy it would have been to really screw up the story by producing the wrong kind of art. When Niimura draws giants, they are impressive. When Niimura draws Barbara the giant slayer, she is awkwardly confident. When Niimura draws the intersection of fantasy and reality, we find ourselves either charmed or chilled according to Niimura’s direction.

In any case, I Kill Giants is the story of Barbara Thorson. Who kills giants. Or so she tells just about everyone.

Barbara is, sigh, precocious and outspoken. She’s a bit geek (she's into D&D and baseball history) and has a difficult homelife. Her interaction with teachers (and school psychologist as a result of her interaction with teachers) doesn’t cry out for emulation. She seems to almost purposely make enemies with those around her. And yet, despite the difficulties she presents for herself (and for the reader who wants to sympathize), she cuts figure as an able protagonist. She’s far from perfect and—for this story at least—we prefer her for it.

Amidst portents of the arrival of a grave doom, the heralding of a coming giant, Barbara has to negotiate a society with which she shares no interest. Against her wishes, the society around her makes many overtures of peace and goodwill. Some make ground while others break it. And all the while, the unseen world becomes increasingly active as the prophesied doom grows ever nearer. In the end, it’s in Barbara’s interactions with both worlds and their inevitable clash that I Kill Giants’ story takes shape.

And it was wonderful to take in.

Pachyderme

by Frederik Peeters (translated by Edward Gauvin, lettered by Lizzie Kaye)

88 pages

SelfMadeHero

ISBN: 1906838607 (Amazon)

Pachyderme occupies a space similar to Kazuo Ishiguro's The Unconsoled. It's bizarre, magical, dreamlike, fuzzy. We know the scenes, the people, the places. We recognize that a story or a couple stories even are unfolding, but there's dissonance. There's a blurry bleary sort of drunkeness that sets in, making discerning the what and the wherefore difficult.

There is a mystery here to unravel and Peeters unfolds it in fits and starts across 88 pages. His art is lush and dreamy. There's intrigue afoot. And it may even be that you finish and don't know exactly what happened. So you read it again. And things clear up some. So you read it again and things clear up a little more. And maybe you understand and maybe you feel like you're now a part of something.

Or maybe you just close the book, confused and troubled, wondering what it was all for.

Age of Bronze

by Eric Shanower

4+ vols

Image

ISBN: 1582402000 (Amazon)

These books take an excruciatingly long time to come out. Volume 3B came out in 2013 and I've seen no word on a vol 3C or 4. I wouldn't be surprised if the series is never completed. That said: still worth it.

Age Of Bronze is a *comprehensive* retelling of the entire events of the Trojan War, combining the details from Homer, Virgil, and other sources. It's long, it's sprawling, it's meticulously illustrated. In this telling Shanower has opted to exclude the gods and their squabbles for what instead is the human actors beliefs about the gods. This was a narrative trick used in Wolfgang Petersen's film Troy (a movie that came out and was forgotten six years after Shanower's book first published). It's a good book and a great book and one worthy of your attention.

Zoo in Winter

by Taniguchi JiroKumar Sivasubramanian)

232 pages

Ponent Mon

ISBN: 1912097311 (Amazon)

A Zoo In Winter is a languid, beautiful piece from a creator who we're sad to see passed. It gives us a historical snapshot of what manga production in the ’60s was like, perhaps Taniguchi investing a bit of autobio into his fiction for the sake of verisimilitude. In any case, this is a quiet story about a somewhat timid young man, trying to find his feet and a direction for his life.

The Sound of the World by Heart

by Giacomo Bevilacqua (localized by Mike Kennedy)

192 pages

Lion Forge

ISBN: 1941302386 (Amazon)

Sam's a photographer for a boutique-published magazine in France. He's in New York recovering from a broken heart and using the opportunity to work on a special project for his editor. He will spend two months without communicating to another human (apart from morning updates to his editor via texting) in the midst of the bustling throng of the metropolis. He can eat at a particular restaurant or his apartment no more than three times in that two month period, forcing him to find ways to interact without speech. A key prop in his operating mode are huge headphones with which he can appear logistically insensible to dialogue.

This book is gorgeous, the illustrations lush and colourful. This is one of my favourite reads from 2017 so far. I can see it fitting in my end-of-year top 10 pretty easily. It's about the romance of living, the romance of a challenge, and the romance of a city. Your experience of the book will definitely be helped if you can give yourself over to the idea that New York City is a living, breathing entity suffused with a kind of special magic. I've been there once and my personal experience said the opposite, but suspending my bias for the space of this book turned it into something wonderful.

Celeste

by INJ Culbard

192 pages

SelfMadeHero

ISBN: 1906838763 (Amazon)

INJ Culbard is one of the most competent illustrators around. His style veers toward simple (a notch more detail in his faces than Stuart Immonen circa Nextwave and Moving Pictures) but he is so expressive that the simplicity suits his work and brand of dynamism. A couple of years ago American readers would probably be largely unfamiliar with him if they hadn't caught his adaptations of Doyle (Holmes), Burroughs (Martian Chronicles), and Lovecraft (Cthulhu mythos), but he's enjoyed a bit more spotlight with both the New Deadwardians and the delightful War Of The Worlds riff, Wild's End (which is actually far more interesting than War Of The Worlds).

Celeste follows three narrative threads: a young albino woman in Britain, a suicidal artist in Japan, and a middle-aged dude stuck in traffic on the 405. Then everybody on earth vanishes except these three. And the other young woman that the albino woman meets, a man stuck in another car on the 405, and the bizarre cast of yokai and other odds and ends that the Japanese man meets. All very strange, all very neat.

With Celeste, Culbard proposes an alternative to the kind of disposable stories that so much of the medium seems to be swamped in, books that can be plowed through without a single thought toward interpretation, toward meaning, toward purpose and end. The book is dreamy and trippy and a bit Twilight-Zoney. Celeste is elegant and bizarre and doesn't forthrightly open itself to the reader. It begs to be mulled. Which makes the coincidence of its lovely illustrations a special treat.

Geis: A Matter of Life and Death

by Alexis Deacon

96 pages

Nobrow

ISBN: 1910620033 (Amazon)

Here's author Alexis Deacon talking about what a geis is.

"I’d grown up with this book of Celtic mythology and folk tales and they very often used this concept of “geis.” The idea is that we all have these “geisa,” these rules we mustn’t break, but you don’t necessarily know what they are. You go to a priest or a wise woman and they would say, you must never speak to a woman wearing purple or you must never eat five peanuts consecutively or you must never jump over one black sheep and two red sheep. You go, okay, got it, no problem–but then you inevitably do all those things. There’s no way of escaping it. Often in the stories the more things they do to get away, the quicker they bring the events about. I really liked that idea of an inescapable fate. I don’t use it in exactly that way but the core is the same."

Geis a dark fantasy series. But not dark fantasy in the overly chatty, grimdark, ironically self-assured manner of we've seen become common today. This is understated and confident without being jabbery. And the art is reminiscent of Kerascoet's in Beautiful Darkness. Lovely, tricky, sinister work.

101–110111–120121–130131–140141–150

151–160161–170171–180181–190191–200

Eagle: The Making Of An Asian American President

by Kaiji Kawaguchi (translated by Carl Gustav Horn)

5 vols

Viz

ISBN: 1569314756 (Amazon)

You may call me a bit of a cynic—and you would be correct in that estimation. So what’s a guy like me doing pretty thoroughly enjoying a book like Eagle: The Making Of An Asian-American President: a book that in many ways is a celebration (or fetishization) of the American electoral process?

Honestly, part of it is novelty. The bare concept alone is interesting: 2264 pages following a candidate’s campaign from the lead-up to the Democratic National Convention all the way through to the results of the Presidential Election—but written by a Japanese creator for a Japanese audience. Seeing how an outsider views and understands and interprets something that remains mysterious even to many Americans is a treasure of cross-cultural appreciation. When he mythologizes Texas, through heavy play on ranchers and late-night T-bones as big as your head, you can see where he’s coming from. When he follows a trail into the sordid realm of labour union politics, American readers may well wonder how closely the author’s original audience could relate (what with the differences in American and Japanese business ethics and practices). And when the book’s candidate-of-choice, Kenneth Yamaoka, a third-gen Japanese-American senator (D-NY) is confronted by some of the racial difficulties that confronted Obama, you wonder how much it hurt to write those sentiments and how much author Kawaguchi was able to empathize with the more hateful elements he had to portray.

Eagle's subtitle (The Making of an Asian-American President) is interesting because you’re pretty sure that Kawaguchi is giving away the whole bag of cookies at the outset. While reading, there may be some doubt in the occasional reader as to the author’s destination, but as the story unfolds, presidential hopeful Yamaoka unveils to be perhaps the ultimate Mary Sue. There is no obstacle that he will not overcome—no scandal that will not either fade from memory instantly or turn out somehow to work in the anointed man’s favour. It might be annoying if Yamaoka was ever really the point of the book. But he’s not.

Kawaguchi’s primary interest seems almost wholly concerned with exploring what it takes to become president of the United States. And since someone is undoubtedly going to become president, for Kawaguchi’s purpose, it hardly matters who. He just needs readers to willingly tag along for the ride—most likely to see just how crazy a ride it actually is.

+ there's a lot of soap-operatic elements for those who get their thrills there.

Monograph by Chris Ware

by Chris Ware, Ira Glass, Francoise Mouly, Art Spiegelman

280 pages

Rizzoli

ISBN: 0847860884 (Amazon)

Monograph is, for those with *any* interest in Chris Ware, a pretty bounty. It's his self-curated gaze into the kind of kooky, really obsessive, and ridiculously talented history of works. There's all kinds of crazy in here, but I'm mostly just glad to finally have this comic in print:

Pantheon

by Hamish Steele

224 pages

Nobrow

ISBN: 1910620203 (Amazon)

This is off the hook bonkers. Also, pretty faithful to the Egyptian myths. Therefore, off the hook bonkers.

You know how the Greek myths are pretty nuts? Rape, incest, Zeus being a giant animorph and screwing basically anything with a hole and making demigod after demigod (cf all this). One lady he seduces by being a ridiculously charming swan.

So yeah, as nutty as Greek mythology is, it reads like Anne Of Green Gables next to the Egyptian brand of the stuff.

With that in mind, Hamish Steele's tongue-in-cheek and deeply gross comic about them is probably the perfect way to encounter and understand the Egyptian mythos. Lots of sex, lots of incest, lots of murder, and lots of other things like one god mixing his and another god's semen into a salad and feeding it to the other god and then later? that god who ate the salad? he gets pregnant and gives birth to the moon god—who had already been around for centuries at that point. ‾\_(ツ)_/‾

It's all very funny and very brightly told and is 100% not for non-debauched children.

Castle Waiting

by Linda Medley

2 vols

Fantagraphics

ISBN: 1606996029 (Amazon)

In Castle Waiting, Linda Medley accomplishes something unique by proposing a medieval fantasy setting and then using it mostly to set stage for a series of character-driven episodes of people who mostly just talk about their lives. The castle at Brambly Hedge is the product of a sleeping beauty-style curse. For a hundred years, the fortress was grown up with a forest of thorns dangerous enough to end the lives of any adventurers who set out to discover the mystery of the place. Generations later, a charming prince finds his way through unscathed, wakes the princess, and the two of them leave the castle (and its servants) behind for a bright and ego-tastic future somewhere less provincial. A generation after that, the only ones left in the castle are the princess’ three handmaidens (now old), and they elect to turn the castle into a sanctuary for those in need.

That was all prologue and at the book’s real beginning, a pregnant Lady Jain arrives seeking safety inside the castle’s walls. She is fleeing from her husband lest he discover her pregnancy by another man and kill her for jealousy. Of course, all of this sounds not exactly untypical of the standard fantasy work. Maybe it’s rare to have a female protagonist open an epic adventure by running away with a baby in the belly, but everything else sounds pretty standard. It’s just that when I said this is where the book begins, it’s also pretty much where the story (in any grand sense of the term) ends.

The moment Jain enters into the Castle Waiting, all larger plot movement halts entirely and nearly all focus homes in upon the development of the relationships between Jain and those who make their home in the castle. Beyond the three handmaidens, there’s the rambunctious bearded nun, the plague-masked Doctor Fell, Sir Chess (the horse-headed knight gallant), Rackham (the werestork fashionista), simple Simon and his widowed mother, and the silent, aloof Iron Henry (the adopted son of dwarves). Each member of the community has a unique and compelling personal history and the simmering of their persons and circumstances makes for enjoyable reading.

Demon

by Jason Shiga

4 vols

First Second

ISBN: 1626724520 (Amazon)

Jason Shiga's story of immortality is kind of a diabolically clever math problem. It twists, it turns, and it constantly has me saying "Oh-ho!" as I turn the page and find everything has changed once more. Also, it's horrifically grusome and delightfully depraved, so—like—please go in eyes wide open and don't get this for your fifth grader.

I Killed Adolf Hitler

by Jason (translated by Kim Thompson)

48 pages

Fantagraphics

ISBN: 1683960084 (Amazon)

Mononymous author Jason crafts instead a work of subtlety in which he explores themes of love and life and second chances (not disimilarly—but perhaps more on point—to how Jonathan Blow would later meditate on similar themes through his popular videogame Braid). And even more, perhaps, I Killed Adolph Hitler concerns the nature of the human creature.

The protagonist is a hitman who will kill anyone without compunction and without any more reason than a paycheck. He exists in a world in which paid assassinations are accepted, commonplace, and legal. Jason, by posing an assassin as hero sheds a different kind of light on Hitler, the protagonist’s next target—and in so doing asks interesting questions about what makes us what we are.